The revelation that the Justice Department is investigating former President Donald Trump for violations of the Espionage Act has provoked a new wave of criticism of that century-old law, with some calling on Congress to narrow the law and at least one senator declaring that it should be repealed altogether. There are in fact very good reasons to criticize the Espionage Act — a law that has cast a dark shadow over free speech and press freedom in this country since its passage — and compelling reasons why Congress should overhaul it. That the law is being used against Trump, however, isn’t one of them.

This much the law’s new critics have right: The Espionage Act is wildly overbroad. We know this from experience. Former President Woodrow Wilson signed the measure into law in 1917 and immediately began using it as an instrument of political repression. During and after the First World War, his administration used the Espionage Act to prosecute thousands of people for legitimate political speech. One of those people was the socialist and labor activist Eugene Debs, who was sentenced to a decade in prison for an anti-war speech that allegedly obstructed military recruitment. (It’s perhaps worth noting, given questions about Trump’s future, that Debs later ran for president from his prison cell.)

Congress amended the Espionage Act after the Second World War, but the amended law, like the original, criminalizes a wide range of activity bearing little resemblance to espionage as the term is usually understood.

A major problem with the law is that it fails to distinguish, on one hand, government insiders who share national security information with foreign powers in order to harm the United States, from, on the other hand, those who share information with the press in order to inform the American public about government misconduct and criminality. After 9/11, successive administrations exploited this defect, using the law again and again to prosecute whistleblowers who shared information with reporters. These prosecutions — of Chelsea Manning, Terry Albury, Reality Winner and Daniel Hale, among others — had the effect of discouraging other insiders from sharing information with the press, of limiting the public’s access to vital information about foreign policy, counterterrorism and war, and of consolidating government control over public discourse on those topics.

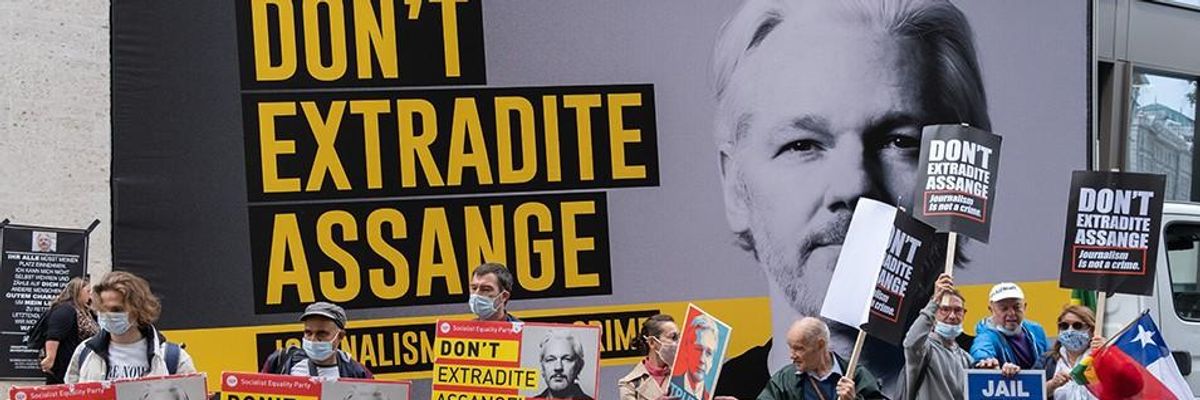

Another major problem with the law is that, on its face, it criminalizes the publication of national security information not just by government insiders but by others as well. It was this aspect of the law that led two prominent legal scholars to characterize the Espionage Act, 50 years ago, as a “loaded gun” pointed at the press, and that more recently has led press freedom groups (including the Knight Institute, which I direct) to decry the Biden administration’s prosecution of Julian Assange. The truth is that it would be absolutely impossible for the press to do its job if it couldn’t publish government secrets, as the journalist Max Frankel famously observed. (Imagine what the debate about counterterrorism policy after 9/11 would have looked like without the reporting about Abu Ghraib, the CIA’s black sites, the torture memos, the warrantless wiretapping program or the drone campaign.) And whether or not Julian Assange is fairly characterized as “the press,” the government’s effort to prosecute him relies on a legal theory that could as readily support a prosecution of the New York Times or the Wall Street Journal.

So the Espionage Act is overbroad in important respects. In some of its possible applications, the law is probably unconstitutional, too. But what does any of that have to do with Trump? Not much.

Trump isn’t a whistleblower or reporter or publisher. There is no serious argument that he retained top secret records so that he could inform the public about government misconduct. The concerns that have led civil liberties and press freedom groups to fear and condemn the Espionage Act simply aren’t present here. Indeed, if the facts are essentially as the Justice Department asserts them to be — that Trump left the White House with scores of top-secret documents, that he failed to adequately secure them, that he refused to return them even after receiving a request from the National Archives and Records Administration and a subpoena from the Department of Justice — even a substantially narrowed criminal regime that better accounted for the First Amendment interests of whistleblowers, journalists and the public would almost certainly reach the conduct that Trump is said to have engaged in here.

All of this said, the Espionage Act’s new critics are right that the law should be amended, even if they are wrong about why. And perhaps we can hope that the attention they are drawing to the law will inspire legislators to do what they should have done many years ago.

Some promising proposals have already been introduced, backed by the left and right. A bipartisan bill unveiled just a few weeks ago by Rep. Ro Khanna (D-Calif.), Rep. Thomas Massie (R-Ky.) and Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) would narrow the Espionage Act to protect journalists and publishers. A proposal from Rep. Rashida Tlaib (D-Mich.) would give defendants charged under the law an opportunity to make the case to a court that their actions were justified. (I advocated for something similar here.)

These kinds of proposals would perhaps not satisfy the Espionage Act’s new critics, at least some of whom seem to be motivated by fealty to Trump rather than actual principle. But by enacting them, or a version of them, Congress could reaffirm press freedom and the public’s right to know at a moment when those things could hardly be more important to our democracy.