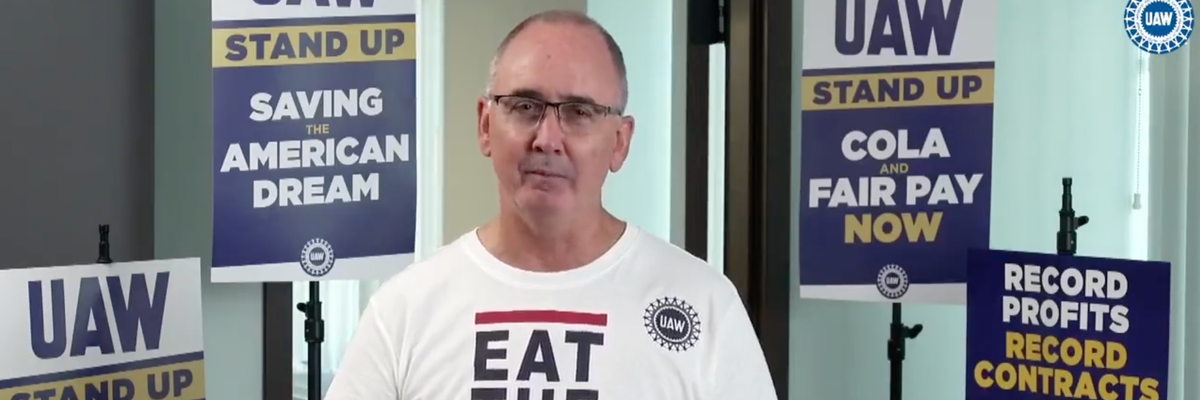

United Auto Workers President Shawn Fain announces progress in the union’s negotiations with the Big Three automakers on October 6, 2023.

The UAW Wins Fight for Just Transition

What the United Auto Workers won from the manufacturers and why it matters so much.

For our economy to move away from climate-harming fossil fuels, the workforce in those industries will suffer job losses. Just Transition refers to a set of proposals designed to help dislocated workers and impacted communities move forward without suffering catastrophic economic harm.

On October 6 of this year, Shawn Fain, the president of the United Auto Workers (UAW), announced that General Motors had agreed to place its electric car battery facilities under the national UAW contract.

“GM’s commitment is a historic step forward,” Fain said, “guaranteeing that the transition to electric vehicles at GM will be a just transition that brings good union jobs to communities across America.”

If the UAW can win protections for laid off workers, Just Transition could become the model for workers (30 million of them since 1996) who suffer through mass layoffs.

The agreement short-circuits industry efforts to make the new battery facilities run on low-wage labor. These green jobs of the future will now come with the higher wages and benefits received by UAW members.

The UAW is also bargaining for a Just Transition program for auto workers who lose their jobs due to layoffs and plant closings. This is likely to be much harder to achieve, but it is perhaps even more important because of the number of workers impacted as well as nearby communities. Called the Working Family Protection Program, it demands that the auto companies “pay UAW members to do community service work” if their jobs are eliminated. Not only will this arrangement protect the livelihoods of workers, but it will also protect the surrounding community’s economic base while providing needed community service employees, paid for by the departing corporations.

The switch to electric vehicles has created the need for both proposals. First, non-union workers at new battery facilities earn less than half the wages of UAW members at internal combustion facilities. Second, fewer parts and therefore fewer workers are needed to build electric vehicles. Layoffs and plant closing are expected to follow the switch from IC to EV. That is why the Family Protection Program is so important. So is winning the right, for the first time, to strike over plant closings. If the UAW can win protections for laid off workers, Just Transition could become the model for workers (30 million of them since 1996) who suffer through mass layoffs.

Just Transition was the brainchild of Tony Mazzocchi, who was a founder of the modern health and safety movement. He understood as early as the 1970s that labor was on a collision course with the budding environmental movement. Mazzocchi recognized that the workers he represented produced poisons and products that contributed to water and air pollution as well as global warming. The day would soon come, he believed, when much of what these workers produced would need to be eliminated to protect our health and the environment. What then, he asked, would happen to these workers?

Mazzocchi reasoned that unless there was a program to protect their livelihoods, these workers would become cannon fodder for authoritarian divisive demagogues who would pit them against “job-killing” environmentalists.

What these workers needed, Mazzocchi believed, would be similar to what he had received after serving in WWII—the GI Bill of Rights. Mazzocchi and millions of veterans were paid a living wage to go to school, in his case to learn how to repair dentures. His tuition at the time, he claimed, was higher than Harvard’s and the government paid for it. Why couldn’t the same be done with every dislocated worker? He wanted to provide the victims of layoffs with their current income and benefits, as well as covering the tuition for the school of their choice. Mazzocchi didn’t want to put a limit on the time workers could draw on such a program, but after getting pushback from many colleagues on the costs, he agreed to a four-year limit.

At first, he called it the Superfund for Workers. After all, money is put aside to clean up the physical environment, why not also take care of the human costs? As one atomic worker picket sign at the time requested: “Treat Workers Like Dirt!” (For more of the Mazzocchi story, see The Man Who Hated Work and Loved Labor.)

In 1995 I changed the name to Just Transition in a talk I gave on behalf of the Oil, Chemical, and Atomic Workers at the Great Lakes International Joint Commission conference in Duluth, Minnesota. The conference concerned the elimination of hazardous chemicals that were harming the Great Lakes ecosystem. In the address, I said:

We ask that any worker that loses his or her job during a sunsetting transition should suffer no net loss of income. No toxic-related worker should be asked to pay a disproportional tax in the form of losing his or her job to achieve the goals of sunsetting. Instead, these costs should be fairly distributed across society. We propose that a special fund be established, a Just Transition fund….

For the sake of these workers, for the sake of their children, our children, and the Great Lakes, let’s join together to build a Just Transition movement.

Brian Kohler, from the Canadian Energy and Paperworkers Union, who also addressed the conference, put Just Transition into his talk as well. From there it traveled the world. Brian skillfully and tirelessly moved the concept through the Canadian labor movement, and then throughout Europe. Eventually he got it included as a vital part of the Paris climate accords. Through countless educational sessions, the Labor Institute shared the idea with thousands of labor union, environmental, and environmental justice activists throughout the U.S. It caught on, because expecting workers to shoulder the cost of societal change was clearly not just.

The reception within the labor movement was often less than enthusiastic. The United Mineworkers (UMW) rejected it as a “golden funeral.” And in truth, most workers in environmentally sensitive industries preferred the security of their jobs to the speculative vision of an unfunded program. Just Transition, until it became a real program paying real dollars, seemed like an illusion–a ticket to the unknown.

But the reality of climate change has altered those perceptions. Oil refinery workers, mine workers, and auto workers are now directly experiencing the dislocation Mazzocchi predicted 50 years ago, when he held the first global warming conference for union leaders. (The UMW now strongly supports Just Transition.) The shift away from fossil fuels and cars that use them, anticipated then, is well underway.

But how can Just Transition become a tangible and reliable program? Where will the money come from? Where is the political will to obtain it?

The UAW has now taken the lead. It is confronting the Big 3 automakers with a financial equation that might rattle them: Lay us off and you’ll have to pay anyway. Instead of the companies shifting jobs overseas or using mass layoffs to get more cash for stock buybacks to please Wall Street and top auto executives, as they’ve been doing for the last 40 years, the UAW is saying: Keep us at work. Otherwise, you’ll be paying the same anyway so that our members can do community service jobs.

Does the UAW have enough clout to pull this off? The jury is out. The auto industry and their Wall Street backers may resist this proposal even more than the stiff wage demands. But the UAW is showing resolve far beyond expectations. If the union finds a way to flex its muscles to secure protection against mass layoffs, it could give hope to millions of victims of corporate abuse.

This is the closest we’ve ever come to a vibrant Just Transition program, with the potential to finally move the idea from an idealistic vision to a compelling rock-solid reality. And successful implementation would certainly mark the beginning of the end of divisive and unproductive labor/environmental clashes.

Tony Mazzocchi spent his lifetime crafting bold proposals to build an empowered working-class movement. The UAW leadership has now grabbed his baton with gusto. Their efforts are without question moving us one step close to a fairer and more just society.

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Les Leopold is the executive director of the Labor Institute and author of the new book, “Wall Street’s War on Workers: How Mass Layoffs and Greed Are Destroying the Working Class and What to Do About It." (2024). Read more of his work on his substack here.

For our economy to move away from climate-harming fossil fuels, the workforce in those industries will suffer job losses. Just Transition refers to a set of proposals designed to help dislocated workers and impacted communities move forward without suffering catastrophic economic harm.

On October 6 of this year, Shawn Fain, the president of the United Auto Workers (UAW), announced that General Motors had agreed to place its electric car battery facilities under the national UAW contract.

“GM’s commitment is a historic step forward,” Fain said, “guaranteeing that the transition to electric vehicles at GM will be a just transition that brings good union jobs to communities across America.”

If the UAW can win protections for laid off workers, Just Transition could become the model for workers (30 million of them since 1996) who suffer through mass layoffs.

The agreement short-circuits industry efforts to make the new battery facilities run on low-wage labor. These green jobs of the future will now come with the higher wages and benefits received by UAW members.

The UAW is also bargaining for a Just Transition program for auto workers who lose their jobs due to layoffs and plant closings. This is likely to be much harder to achieve, but it is perhaps even more important because of the number of workers impacted as well as nearby communities. Called the Working Family Protection Program, it demands that the auto companies “pay UAW members to do community service work” if their jobs are eliminated. Not only will this arrangement protect the livelihoods of workers, but it will also protect the surrounding community’s economic base while providing needed community service employees, paid for by the departing corporations.

The switch to electric vehicles has created the need for both proposals. First, non-union workers at new battery facilities earn less than half the wages of UAW members at internal combustion facilities. Second, fewer parts and therefore fewer workers are needed to build electric vehicles. Layoffs and plant closing are expected to follow the switch from IC to EV. That is why the Family Protection Program is so important. So is winning the right, for the first time, to strike over plant closings. If the UAW can win protections for laid off workers, Just Transition could become the model for workers (30 million of them since 1996) who suffer through mass layoffs.

Just Transition was the brainchild of Tony Mazzocchi, who was a founder of the modern health and safety movement. He understood as early as the 1970s that labor was on a collision course with the budding environmental movement. Mazzocchi recognized that the workers he represented produced poisons and products that contributed to water and air pollution as well as global warming. The day would soon come, he believed, when much of what these workers produced would need to be eliminated to protect our health and the environment. What then, he asked, would happen to these workers?

Mazzocchi reasoned that unless there was a program to protect their livelihoods, these workers would become cannon fodder for authoritarian divisive demagogues who would pit them against “job-killing” environmentalists.

What these workers needed, Mazzocchi believed, would be similar to what he had received after serving in WWII—the GI Bill of Rights. Mazzocchi and millions of veterans were paid a living wage to go to school, in his case to learn how to repair dentures. His tuition at the time, he claimed, was higher than Harvard’s and the government paid for it. Why couldn’t the same be done with every dislocated worker? He wanted to provide the victims of layoffs with their current income and benefits, as well as covering the tuition for the school of their choice. Mazzocchi didn’t want to put a limit on the time workers could draw on such a program, but after getting pushback from many colleagues on the costs, he agreed to a four-year limit.

At first, he called it the Superfund for Workers. After all, money is put aside to clean up the physical environment, why not also take care of the human costs? As one atomic worker picket sign at the time requested: “Treat Workers Like Dirt!” (For more of the Mazzocchi story, see The Man Who Hated Work and Loved Labor.)

In 1995 I changed the name to Just Transition in a talk I gave on behalf of the Oil, Chemical, and Atomic Workers at the Great Lakes International Joint Commission conference in Duluth, Minnesota. The conference concerned the elimination of hazardous chemicals that were harming the Great Lakes ecosystem. In the address, I said:

We ask that any worker that loses his or her job during a sunsetting transition should suffer no net loss of income. No toxic-related worker should be asked to pay a disproportional tax in the form of losing his or her job to achieve the goals of sunsetting. Instead, these costs should be fairly distributed across society. We propose that a special fund be established, a Just Transition fund….

For the sake of these workers, for the sake of their children, our children, and the Great Lakes, let’s join together to build a Just Transition movement.

Brian Kohler, from the Canadian Energy and Paperworkers Union, who also addressed the conference, put Just Transition into his talk as well. From there it traveled the world. Brian skillfully and tirelessly moved the concept through the Canadian labor movement, and then throughout Europe. Eventually he got it included as a vital part of the Paris climate accords. Through countless educational sessions, the Labor Institute shared the idea with thousands of labor union, environmental, and environmental justice activists throughout the U.S. It caught on, because expecting workers to shoulder the cost of societal change was clearly not just.

The reception within the labor movement was often less than enthusiastic. The United Mineworkers (UMW) rejected it as a “golden funeral.” And in truth, most workers in environmentally sensitive industries preferred the security of their jobs to the speculative vision of an unfunded program. Just Transition, until it became a real program paying real dollars, seemed like an illusion–a ticket to the unknown.

But the reality of climate change has altered those perceptions. Oil refinery workers, mine workers, and auto workers are now directly experiencing the dislocation Mazzocchi predicted 50 years ago, when he held the first global warming conference for union leaders. (The UMW now strongly supports Just Transition.) The shift away from fossil fuels and cars that use them, anticipated then, is well underway.

But how can Just Transition become a tangible and reliable program? Where will the money come from? Where is the political will to obtain it?

The UAW has now taken the lead. It is confronting the Big 3 automakers with a financial equation that might rattle them: Lay us off and you’ll have to pay anyway. Instead of the companies shifting jobs overseas or using mass layoffs to get more cash for stock buybacks to please Wall Street and top auto executives, as they’ve been doing for the last 40 years, the UAW is saying: Keep us at work. Otherwise, you’ll be paying the same anyway so that our members can do community service jobs.

Does the UAW have enough clout to pull this off? The jury is out. The auto industry and their Wall Street backers may resist this proposal even more than the stiff wage demands. But the UAW is showing resolve far beyond expectations. If the union finds a way to flex its muscles to secure protection against mass layoffs, it could give hope to millions of victims of corporate abuse.

This is the closest we’ve ever come to a vibrant Just Transition program, with the potential to finally move the idea from an idealistic vision to a compelling rock-solid reality. And successful implementation would certainly mark the beginning of the end of divisive and unproductive labor/environmental clashes.

Tony Mazzocchi spent his lifetime crafting bold proposals to build an empowered working-class movement. The UAW leadership has now grabbed his baton with gusto. Their efforts are without question moving us one step close to a fairer and more just society.

- Khanna and UAW President Demand 'New Model' That Puts Workers, Climate Over Profits ›

- UAW Ramps Up Pressure on Biden to Protect Workers in Electric Vehicle Transition ›

- Only a Just Transition Can End This Anti-Worker Race to the Bottom ›

- Green Groups Stand With UAW in Fight to Protect Autoworkers During EV Transition ›

- UAW Holds Off on Endorsing Biden in Bid to Secure Just EV Transition ›

- As Auto Strike Looms, Biden Admin Puts $15.5 Billion Toward Just Transition to EVs ›

- Opinion | No Car Making on a Dead Planet | Common Dreams ›

- Opinion | The UAW’s Game Changer: The Right to Strike Over Mass Layoffs | Common Dreams ›

- Opinion | UAW Strike Put Us on Better Road to Energy Transition | Common Dreams ›

Les Leopold is the executive director of the Labor Institute and author of the new book, “Wall Street’s War on Workers: How Mass Layoffs and Greed Are Destroying the Working Class and What to Do About It." (2024). Read more of his work on his substack here.

For our economy to move away from climate-harming fossil fuels, the workforce in those industries will suffer job losses. Just Transition refers to a set of proposals designed to help dislocated workers and impacted communities move forward without suffering catastrophic economic harm.

On October 6 of this year, Shawn Fain, the president of the United Auto Workers (UAW), announced that General Motors had agreed to place its electric car battery facilities under the national UAW contract.

“GM’s commitment is a historic step forward,” Fain said, “guaranteeing that the transition to electric vehicles at GM will be a just transition that brings good union jobs to communities across America.”

If the UAW can win protections for laid off workers, Just Transition could become the model for workers (30 million of them since 1996) who suffer through mass layoffs.

The agreement short-circuits industry efforts to make the new battery facilities run on low-wage labor. These green jobs of the future will now come with the higher wages and benefits received by UAW members.

The UAW is also bargaining for a Just Transition program for auto workers who lose their jobs due to layoffs and plant closings. This is likely to be much harder to achieve, but it is perhaps even more important because of the number of workers impacted as well as nearby communities. Called the Working Family Protection Program, it demands that the auto companies “pay UAW members to do community service work” if their jobs are eliminated. Not only will this arrangement protect the livelihoods of workers, but it will also protect the surrounding community’s economic base while providing needed community service employees, paid for by the departing corporations.

The switch to electric vehicles has created the need for both proposals. First, non-union workers at new battery facilities earn less than half the wages of UAW members at internal combustion facilities. Second, fewer parts and therefore fewer workers are needed to build electric vehicles. Layoffs and plant closing are expected to follow the switch from IC to EV. That is why the Family Protection Program is so important. So is winning the right, for the first time, to strike over plant closings. If the UAW can win protections for laid off workers, Just Transition could become the model for workers (30 million of them since 1996) who suffer through mass layoffs.

Just Transition was the brainchild of Tony Mazzocchi, who was a founder of the modern health and safety movement. He understood as early as the 1970s that labor was on a collision course with the budding environmental movement. Mazzocchi recognized that the workers he represented produced poisons and products that contributed to water and air pollution as well as global warming. The day would soon come, he believed, when much of what these workers produced would need to be eliminated to protect our health and the environment. What then, he asked, would happen to these workers?

Mazzocchi reasoned that unless there was a program to protect their livelihoods, these workers would become cannon fodder for authoritarian divisive demagogues who would pit them against “job-killing” environmentalists.

What these workers needed, Mazzocchi believed, would be similar to what he had received after serving in WWII—the GI Bill of Rights. Mazzocchi and millions of veterans were paid a living wage to go to school, in his case to learn how to repair dentures. His tuition at the time, he claimed, was higher than Harvard’s and the government paid for it. Why couldn’t the same be done with every dislocated worker? He wanted to provide the victims of layoffs with their current income and benefits, as well as covering the tuition for the school of their choice. Mazzocchi didn’t want to put a limit on the time workers could draw on such a program, but after getting pushback from many colleagues on the costs, he agreed to a four-year limit.

At first, he called it the Superfund for Workers. After all, money is put aside to clean up the physical environment, why not also take care of the human costs? As one atomic worker picket sign at the time requested: “Treat Workers Like Dirt!” (For more of the Mazzocchi story, see The Man Who Hated Work and Loved Labor.)

In 1995 I changed the name to Just Transition in a talk I gave on behalf of the Oil, Chemical, and Atomic Workers at the Great Lakes International Joint Commission conference in Duluth, Minnesota. The conference concerned the elimination of hazardous chemicals that were harming the Great Lakes ecosystem. In the address, I said:

We ask that any worker that loses his or her job during a sunsetting transition should suffer no net loss of income. No toxic-related worker should be asked to pay a disproportional tax in the form of losing his or her job to achieve the goals of sunsetting. Instead, these costs should be fairly distributed across society. We propose that a special fund be established, a Just Transition fund….

For the sake of these workers, for the sake of their children, our children, and the Great Lakes, let’s join together to build a Just Transition movement.

Brian Kohler, from the Canadian Energy and Paperworkers Union, who also addressed the conference, put Just Transition into his talk as well. From there it traveled the world. Brian skillfully and tirelessly moved the concept through the Canadian labor movement, and then throughout Europe. Eventually he got it included as a vital part of the Paris climate accords. Through countless educational sessions, the Labor Institute shared the idea with thousands of labor union, environmental, and environmental justice activists throughout the U.S. It caught on, because expecting workers to shoulder the cost of societal change was clearly not just.

The reception within the labor movement was often less than enthusiastic. The United Mineworkers (UMW) rejected it as a “golden funeral.” And in truth, most workers in environmentally sensitive industries preferred the security of their jobs to the speculative vision of an unfunded program. Just Transition, until it became a real program paying real dollars, seemed like an illusion–a ticket to the unknown.

But the reality of climate change has altered those perceptions. Oil refinery workers, mine workers, and auto workers are now directly experiencing the dislocation Mazzocchi predicted 50 years ago, when he held the first global warming conference for union leaders. (The UMW now strongly supports Just Transition.) The shift away from fossil fuels and cars that use them, anticipated then, is well underway.

But how can Just Transition become a tangible and reliable program? Where will the money come from? Where is the political will to obtain it?

The UAW has now taken the lead. It is confronting the Big 3 automakers with a financial equation that might rattle them: Lay us off and you’ll have to pay anyway. Instead of the companies shifting jobs overseas or using mass layoffs to get more cash for stock buybacks to please Wall Street and top auto executives, as they’ve been doing for the last 40 years, the UAW is saying: Keep us at work. Otherwise, you’ll be paying the same anyway so that our members can do community service jobs.

Does the UAW have enough clout to pull this off? The jury is out. The auto industry and their Wall Street backers may resist this proposal even more than the stiff wage demands. But the UAW is showing resolve far beyond expectations. If the union finds a way to flex its muscles to secure protection against mass layoffs, it could give hope to millions of victims of corporate abuse.

This is the closest we’ve ever come to a vibrant Just Transition program, with the potential to finally move the idea from an idealistic vision to a compelling rock-solid reality. And successful implementation would certainly mark the beginning of the end of divisive and unproductive labor/environmental clashes.

Tony Mazzocchi spent his lifetime crafting bold proposals to build an empowered working-class movement. The UAW leadership has now grabbed his baton with gusto. Their efforts are without question moving us one step close to a fairer and more just society.

- Khanna and UAW President Demand 'New Model' That Puts Workers, Climate Over Profits ›

- UAW Ramps Up Pressure on Biden to Protect Workers in Electric Vehicle Transition ›

- Only a Just Transition Can End This Anti-Worker Race to the Bottom ›

- Green Groups Stand With UAW in Fight to Protect Autoworkers During EV Transition ›

- UAW Holds Off on Endorsing Biden in Bid to Secure Just EV Transition ›

- As Auto Strike Looms, Biden Admin Puts $15.5 Billion Toward Just Transition to EVs ›

- Opinion | No Car Making on a Dead Planet | Common Dreams ›

- Opinion | The UAW’s Game Changer: The Right to Strike Over Mass Layoffs | Common Dreams ›

- Opinion | UAW Strike Put Us on Better Road to Energy Transition | Common Dreams ›