SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

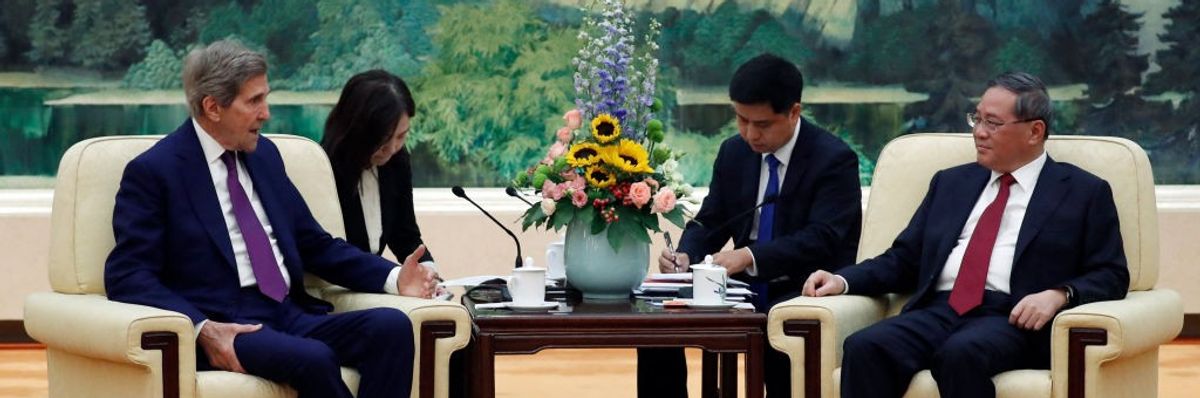

U.S. Climate Envoy John Kerry (L) and China’s Premier Li Qiang attend a meeting at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing on July 18, 2023.

As Climate Envoy John Kerry visits Beijing, our two nations must overcome their deep mutual distrust quickly if we’re to have any hope of reducing global emissions fast enough to blunt the worst climate impacts.

The wildfires, floods, and record temperatures hitting America and the world this month underscore the vital importance of John Kerry’s efforts to revive U.S.-China climate talks during his trip to Beijing.

The U.S. climate envoy kicked off three days of talks in China on Monday. Earlier discussions had been suspended in the wake of Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s controversial visit to Taiwan in the summer of 2022.

Restoring meaningful climate U.S.-China cooperation—as Secretary Antony Blinken rightly pledged during his recent visit to China—is among the Biden administration’s most consequential diplomatic goals. The future of our planet depends on the two countries getting it right. Kerry struck the right note prior to his meeting with his Chinese counterpart Xie Zhenhua, stating that the world demands “we make progress rapidly and significantly.”

Washington and Beijing alike must recognize this is a two-way street. The dynamic cannot be just one side acting as the moral arbiter—telling the other what to do and then penalizing it for not responding.

For his part, Xie said at the beginning of the meeting Monday that he hoped the two nations were entering a period of “stable relations,” and that they should “seek common ground while shelving our differences” and called for talks to be “candid and in-depth.”

It is true that our two nations must overcome their deep mutual distrust quickly to forge climate cooperation if we’re to have any hope of reducing global emissions fast enough to blunt the worst climate impacts, and begin helping countries adapt to warming that’s already baked in.

But Washington and Beijing alike must recognize this is a two-way street. The dynamic cannot be just one side acting as the moral arbiter—telling the other what to do and then penalizing it for not responding. Both have to ask more of each other, separately and jointly.

There’s no question that the surge in China’s coal use is a threat to the planet; Kerry will be right to pressure the Chinese to do more to address this. But the United States should similarly be prepared to discuss its own role in erecting barriers to global emissions reductions, such as tariffs on clean energy products, Washington’s expansion of domestic fossil projects, and the major deficit America is running on international climate financing to the Green Climate Fund and other similar organizations.

It would be helpful if China contributed to international climate financing and Kerry will doubtlessly encourage it to do so. But the onus on this, as defined in the UNFCCC framework agreements, falls on countries with far higher standards of living such as the United States. Kerry recently flatly said the United States would, under “no circumstances,” contribute to the new loss and damage fund that has been agreed upon at last year’s climate talks to compensate poorer countries for irreversible damage from climate change.

Both China and the United States should also work to reduce methane emissions and share best practices on renewable electricity integration into the grid, as per their joint statement during the 2021 COP26 in Glasgow. But they should go beyond these. Hard-to-decarbonize industrial and longer-distance transport sectors will benefit greatly from intensive scientific and technical cooperation between the two countries.

Washington and Beijing can also work together to increase humanitarian assistance and disaster relief preparedness in the regions that are most vulnerable to extreme weather in the Global South, like parts of Southeast Asia, South Asia, and Africa.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

The wildfires, floods, and record temperatures hitting America and the world this month underscore the vital importance of John Kerry’s efforts to revive U.S.-China climate talks during his trip to Beijing.

The U.S. climate envoy kicked off three days of talks in China on Monday. Earlier discussions had been suspended in the wake of Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s controversial visit to Taiwan in the summer of 2022.

Restoring meaningful climate U.S.-China cooperation—as Secretary Antony Blinken rightly pledged during his recent visit to China—is among the Biden administration’s most consequential diplomatic goals. The future of our planet depends on the two countries getting it right. Kerry struck the right note prior to his meeting with his Chinese counterpart Xie Zhenhua, stating that the world demands “we make progress rapidly and significantly.”

Washington and Beijing alike must recognize this is a two-way street. The dynamic cannot be just one side acting as the moral arbiter—telling the other what to do and then penalizing it for not responding.

For his part, Xie said at the beginning of the meeting Monday that he hoped the two nations were entering a period of “stable relations,” and that they should “seek common ground while shelving our differences” and called for talks to be “candid and in-depth.”

It is true that our two nations must overcome their deep mutual distrust quickly to forge climate cooperation if we’re to have any hope of reducing global emissions fast enough to blunt the worst climate impacts, and begin helping countries adapt to warming that’s already baked in.

But Washington and Beijing alike must recognize this is a two-way street. The dynamic cannot be just one side acting as the moral arbiter—telling the other what to do and then penalizing it for not responding. Both have to ask more of each other, separately and jointly.

There’s no question that the surge in China’s coal use is a threat to the planet; Kerry will be right to pressure the Chinese to do more to address this. But the United States should similarly be prepared to discuss its own role in erecting barriers to global emissions reductions, such as tariffs on clean energy products, Washington’s expansion of domestic fossil projects, and the major deficit America is running on international climate financing to the Green Climate Fund and other similar organizations.

It would be helpful if China contributed to international climate financing and Kerry will doubtlessly encourage it to do so. But the onus on this, as defined in the UNFCCC framework agreements, falls on countries with far higher standards of living such as the United States. Kerry recently flatly said the United States would, under “no circumstances,” contribute to the new loss and damage fund that has been agreed upon at last year’s climate talks to compensate poorer countries for irreversible damage from climate change.

Both China and the United States should also work to reduce methane emissions and share best practices on renewable electricity integration into the grid, as per their joint statement during the 2021 COP26 in Glasgow. But they should go beyond these. Hard-to-decarbonize industrial and longer-distance transport sectors will benefit greatly from intensive scientific and technical cooperation between the two countries.

Washington and Beijing can also work together to increase humanitarian assistance and disaster relief preparedness in the regions that are most vulnerable to extreme weather in the Global South, like parts of Southeast Asia, South Asia, and Africa.

The wildfires, floods, and record temperatures hitting America and the world this month underscore the vital importance of John Kerry’s efforts to revive U.S.-China climate talks during his trip to Beijing.

The U.S. climate envoy kicked off three days of talks in China on Monday. Earlier discussions had been suspended in the wake of Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s controversial visit to Taiwan in the summer of 2022.

Restoring meaningful climate U.S.-China cooperation—as Secretary Antony Blinken rightly pledged during his recent visit to China—is among the Biden administration’s most consequential diplomatic goals. The future of our planet depends on the two countries getting it right. Kerry struck the right note prior to his meeting with his Chinese counterpart Xie Zhenhua, stating that the world demands “we make progress rapidly and significantly.”

Washington and Beijing alike must recognize this is a two-way street. The dynamic cannot be just one side acting as the moral arbiter—telling the other what to do and then penalizing it for not responding.

For his part, Xie said at the beginning of the meeting Monday that he hoped the two nations were entering a period of “stable relations,” and that they should “seek common ground while shelving our differences” and called for talks to be “candid and in-depth.”

It is true that our two nations must overcome their deep mutual distrust quickly to forge climate cooperation if we’re to have any hope of reducing global emissions fast enough to blunt the worst climate impacts, and begin helping countries adapt to warming that’s already baked in.

But Washington and Beijing alike must recognize this is a two-way street. The dynamic cannot be just one side acting as the moral arbiter—telling the other what to do and then penalizing it for not responding. Both have to ask more of each other, separately and jointly.

There’s no question that the surge in China’s coal use is a threat to the planet; Kerry will be right to pressure the Chinese to do more to address this. But the United States should similarly be prepared to discuss its own role in erecting barriers to global emissions reductions, such as tariffs on clean energy products, Washington’s expansion of domestic fossil projects, and the major deficit America is running on international climate financing to the Green Climate Fund and other similar organizations.

It would be helpful if China contributed to international climate financing and Kerry will doubtlessly encourage it to do so. But the onus on this, as defined in the UNFCCC framework agreements, falls on countries with far higher standards of living such as the United States. Kerry recently flatly said the United States would, under “no circumstances,” contribute to the new loss and damage fund that has been agreed upon at last year’s climate talks to compensate poorer countries for irreversible damage from climate change.

Both China and the United States should also work to reduce methane emissions and share best practices on renewable electricity integration into the grid, as per their joint statement during the 2021 COP26 in Glasgow. But they should go beyond these. Hard-to-decarbonize industrial and longer-distance transport sectors will benefit greatly from intensive scientific and technical cooperation between the two countries.

Washington and Beijing can also work together to increase humanitarian assistance and disaster relief preparedness in the regions that are most vulnerable to extreme weather in the Global South, like parts of Southeast Asia, South Asia, and Africa.