SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

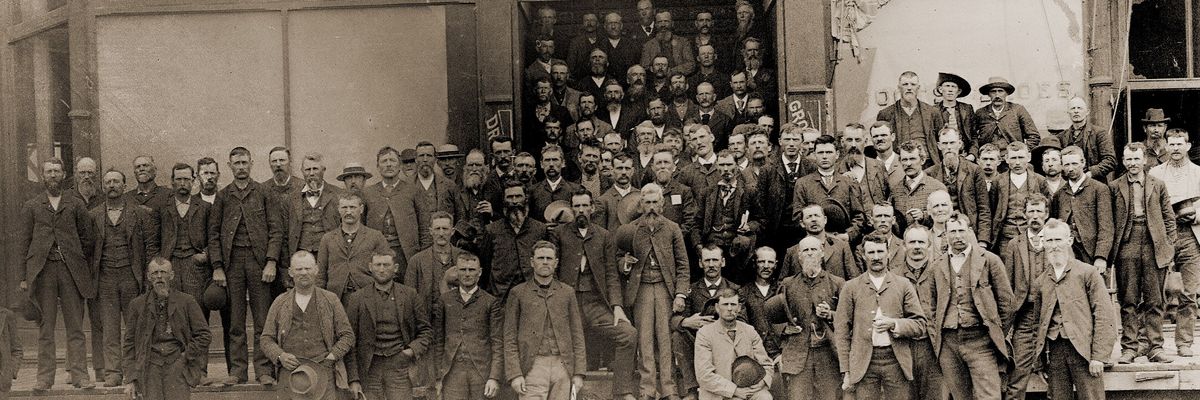

The Independent People’s Party (Populist) Convention at Columbus, Nebraska, on July 15, 1890.

In a new book, author Steve Babson recounts the history of the original 19th-century Populists who would have been would have been shocked to find the word applied to a future president who flaunted his wealth.

Pity the poor Populists—or the memory thereof. If those late-19th century American radical democrats were to have imagined if and how they might be remembered in the third millennium, “little to not-at-all” might have seemed a reasonable expectation. But certainly they would have been shocked to find the word “populist” applied to a future president who flaunted, and even exaggerated, his wealth, when what they were all about was challenging the out-of-control wealth and power of the “Robber Barons” of their day, to the end of democratizing their grip on the nation economy.

And they would have likely been horrified by the likes of a recent New York Times Magazine article, “The President, the Soccer Hooligans, and an Underworld ‘House of Horrors,’” in which Robert F. Worth speaks of Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban’s hope that admitting Serbia to the European Union could help “steer the European Club in a more populist and less democratic direction.”

No doubt they would have asked if there was not someone who would set the record straight. As Steve Babson—who has set himself the task of doing just that in Forgotten Populists: When Farmers Turned Left to Save Democracy—writes, “The People’s Party of 1892 was the only substantial movement in U.S. history to actually call itself Populist,” whereas, “the label currently serves as a sly pejorative, hinting at the unreliable behavior and hidden agenda of anyone who challenges established authority”—and, as we see above, maybe not just hinting.

The Alliance/Populist era saw the emergence of that distinctively American debate, in which the representatives of the monied class denounce their opponents as socialists, while the representatives of the working classes deny that their ideas are socialistic—rather than acknowledging that many elements of their program would indeed involve greater democratic control of the economy—because in the United States, the idea is deemed beyond the pale.

The actual historical Populists were of an age when farmers constituted 40% of the American workforce, compared to 2% today (Babson notes that Bill Gates is now “the nation’s largest private farm owner”), while new technologies were facilitating the concentration of previously unimaginable wealth in the hands of a few gentlemen who more than matched the recent White House resident in their conviction that their wealth was a good thing not only for themselves, but for the entire nation.

As the book recounts, John D. Rockefeller, whose wealth came from oil, would declare that “God gave me my money,” while stock speculator and railroad owner Jay Gould told the U.S. Senate that “We have made the country rich... We have developed the country.” Steel magnate Andrew Carnegie, who would become famously responsible for the armed repression of the 1892 Homestead Steel strike, nonetheless predicted a future “reign of harmony,” characterized by the beneficent philanthropy of members of his class who would spend this money far more wisely than the public “would or could have done for itself.”

The Populists grew out of the Farmers’ Alliance and Cooperative Union that spread from Texas in the 1870s. By 1890, its membership, Babson writes, “had swelled well beyond one million, including not only debt-burdened farmers, but a wide range of allies in small towns and villages who were also struggling with poverty and economic insecurity.” Many of the estimated upwards-of-10,000 local chapters, or “sub-Alliances” that sprouted throughout the South were religiously oriented, generally of the “Social Christian” variety. Perhaps as many as a quarter of a million women were involved. Racial politics reflected the regions, with the Northern Alliance open to Black and white, while separate Southern and Colored Alliances operated in the south, the latter under far more restricted parameters.

Generally sharing the common goal of a “Cooperative Commonwealth” of the producing classes with organizations such as the Knights of Labor—the nation’s earliest mass union—and the still-existing Grange, along the way Alliance members put together more than 300 local cooperatives as vehicles for farmers to collectively sell their crops and purchase supplies. The owning classes responded by promptly closing their own ranks: Bankers refused loans to Cooperative Exchanges; manufacturers refused to sell to them; grain merchants and cotton buyers declined to buy from Alliance bundlers; regular merchants undersold cooperative stores in order to drive them under before returning to their previous uncompetitive prices.

Faced with the problem of insufficient capital that sinks so many cooperative organizations, the Alliances decided that if the federal government could provide the railroad barons with free land to build railroads on which they could then overcharge the farmer for shipping his goods, it could just as well build public warehouses—which they called “subtreasuries”—where farmers could store their crop, thereby avoiding the type of harvest-time glut that typically forced them to sell their produce below its value.

In 1890, the Kansas Alliance stunned the nation by taking to the ballot and sending five of its people to Congress and winning control of the state legislature; Nebraska had similar success.

Two years later, the effort went national with the formation of the People’s Party that would take 50 Congressional seats in 16 states, along with seven governorships. James Weaver, the party’s presidential nominee, carried five states—becoming the only “third party” candidate to win Electoral College votes during the entire period between the Civil War and former president Theodore Roosevelt’s 1912 “Bullmoose” campaign. And yet his vote amounted to less than 9% of the nationwide total, the party proving unable to truly go national in such a brief time.

Author Steve Babson (n.b., a longtime friend of this reviewer) is the author or co-author of six previous books, serious history all, a background reflected in this book’s overall careful presentation and assessment. In considering both the degree to which successful collaboration between white and Black Populists exceeded the norm of the time, as well as the instances of failure to buck that norm when called for, he cites Martin Luther King’s judgement that the Populists “began uniting the Negro and white masses into a voting block that threatened to drive the Bourbon interests from the command posts of political power.”

But with this book, Babson also reaches back to deeper roots, in Popular Economic Press, the rubric under which he and illustrator and wife Nancy Brigham produced the 1973, Why Do We Spend so Much Money? Like that work, Forgotten Populists is large format, heavily illustrated, aimed at people who don’t already belong to the History Book Club, and meant to be of use in the current political fray.

Babson devotes particular attention to the question of how the word “populist” has degenerated from the reality of the actual Populists of the past into its current usage “to vilify rowdy commoners when they challenge favored elites.” The Alliance/Populist era saw the emergence of that distinctively American debate, in which the representatives of the monied class denounce their opponents as socialists, while the representatives of the working classes deny that their ideas are socialistic—rather than acknowledging that many elements of their program would indeed involve greater democratic control of the economy—because in the United States, the idea is deemed beyond the pale.

With a level of scholarship one might not expect to find in a publication aimed at such a general audience, Babson specifically traces the transformation of the word’s usage back to the days of the 1950s Red Scare era, when a prominent historian like Richard Hofstadter “offered a bizarre alchemy: the roots of McCarthyism... were to be found in the very populism that he and others had praised before the Red Scare.” This despite the fact that the aims of the Wisconsin Republican Senator Joseph McCarthy were entirely at odds with those of the 19th-century party.

Whether your interest in American politics lies primarily in the past or the present, your time will be well spent with this book that packs so much information in so relatively few words.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

Pity the poor Populists—or the memory thereof. If those late-19th century American radical democrats were to have imagined if and how they might be remembered in the third millennium, “little to not-at-all” might have seemed a reasonable expectation. But certainly they would have been shocked to find the word “populist” applied to a future president who flaunted, and even exaggerated, his wealth, when what they were all about was challenging the out-of-control wealth and power of the “Robber Barons” of their day, to the end of democratizing their grip on the nation economy.

And they would have likely been horrified by the likes of a recent New York Times Magazine article, “The President, the Soccer Hooligans, and an Underworld ‘House of Horrors,’” in which Robert F. Worth speaks of Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban’s hope that admitting Serbia to the European Union could help “steer the European Club in a more populist and less democratic direction.”

No doubt they would have asked if there was not someone who would set the record straight. As Steve Babson—who has set himself the task of doing just that in Forgotten Populists: When Farmers Turned Left to Save Democracy—writes, “The People’s Party of 1892 was the only substantial movement in U.S. history to actually call itself Populist,” whereas, “the label currently serves as a sly pejorative, hinting at the unreliable behavior and hidden agenda of anyone who challenges established authority”—and, as we see above, maybe not just hinting.

The Alliance/Populist era saw the emergence of that distinctively American debate, in which the representatives of the monied class denounce their opponents as socialists, while the representatives of the working classes deny that their ideas are socialistic—rather than acknowledging that many elements of their program would indeed involve greater democratic control of the economy—because in the United States, the idea is deemed beyond the pale.

The actual historical Populists were of an age when farmers constituted 40% of the American workforce, compared to 2% today (Babson notes that Bill Gates is now “the nation’s largest private farm owner”), while new technologies were facilitating the concentration of previously unimaginable wealth in the hands of a few gentlemen who more than matched the recent White House resident in their conviction that their wealth was a good thing not only for themselves, but for the entire nation.

As the book recounts, John D. Rockefeller, whose wealth came from oil, would declare that “God gave me my money,” while stock speculator and railroad owner Jay Gould told the U.S. Senate that “We have made the country rich... We have developed the country.” Steel magnate Andrew Carnegie, who would become famously responsible for the armed repression of the 1892 Homestead Steel strike, nonetheless predicted a future “reign of harmony,” characterized by the beneficent philanthropy of members of his class who would spend this money far more wisely than the public “would or could have done for itself.”

The Populists grew out of the Farmers’ Alliance and Cooperative Union that spread from Texas in the 1870s. By 1890, its membership, Babson writes, “had swelled well beyond one million, including not only debt-burdened farmers, but a wide range of allies in small towns and villages who were also struggling with poverty and economic insecurity.” Many of the estimated upwards-of-10,000 local chapters, or “sub-Alliances” that sprouted throughout the South were religiously oriented, generally of the “Social Christian” variety. Perhaps as many as a quarter of a million women were involved. Racial politics reflected the regions, with the Northern Alliance open to Black and white, while separate Southern and Colored Alliances operated in the south, the latter under far more restricted parameters.

Generally sharing the common goal of a “Cooperative Commonwealth” of the producing classes with organizations such as the Knights of Labor—the nation’s earliest mass union—and the still-existing Grange, along the way Alliance members put together more than 300 local cooperatives as vehicles for farmers to collectively sell their crops and purchase supplies. The owning classes responded by promptly closing their own ranks: Bankers refused loans to Cooperative Exchanges; manufacturers refused to sell to them; grain merchants and cotton buyers declined to buy from Alliance bundlers; regular merchants undersold cooperative stores in order to drive them under before returning to their previous uncompetitive prices.

Faced with the problem of insufficient capital that sinks so many cooperative organizations, the Alliances decided that if the federal government could provide the railroad barons with free land to build railroads on which they could then overcharge the farmer for shipping his goods, it could just as well build public warehouses—which they called “subtreasuries”—where farmers could store their crop, thereby avoiding the type of harvest-time glut that typically forced them to sell their produce below its value.

In 1890, the Kansas Alliance stunned the nation by taking to the ballot and sending five of its people to Congress and winning control of the state legislature; Nebraska had similar success.

Two years later, the effort went national with the formation of the People’s Party that would take 50 Congressional seats in 16 states, along with seven governorships. James Weaver, the party’s presidential nominee, carried five states—becoming the only “third party” candidate to win Electoral College votes during the entire period between the Civil War and former president Theodore Roosevelt’s 1912 “Bullmoose” campaign. And yet his vote amounted to less than 9% of the nationwide total, the party proving unable to truly go national in such a brief time.

Author Steve Babson (n.b., a longtime friend of this reviewer) is the author or co-author of six previous books, serious history all, a background reflected in this book’s overall careful presentation and assessment. In considering both the degree to which successful collaboration between white and Black Populists exceeded the norm of the time, as well as the instances of failure to buck that norm when called for, he cites Martin Luther King’s judgement that the Populists “began uniting the Negro and white masses into a voting block that threatened to drive the Bourbon interests from the command posts of political power.”

But with this book, Babson also reaches back to deeper roots, in Popular Economic Press, the rubric under which he and illustrator and wife Nancy Brigham produced the 1973, Why Do We Spend so Much Money? Like that work, Forgotten Populists is large format, heavily illustrated, aimed at people who don’t already belong to the History Book Club, and meant to be of use in the current political fray.

Babson devotes particular attention to the question of how the word “populist” has degenerated from the reality of the actual Populists of the past into its current usage “to vilify rowdy commoners when they challenge favored elites.” The Alliance/Populist era saw the emergence of that distinctively American debate, in which the representatives of the monied class denounce their opponents as socialists, while the representatives of the working classes deny that their ideas are socialistic—rather than acknowledging that many elements of their program would indeed involve greater democratic control of the economy—because in the United States, the idea is deemed beyond the pale.

With a level of scholarship one might not expect to find in a publication aimed at such a general audience, Babson specifically traces the transformation of the word’s usage back to the days of the 1950s Red Scare era, when a prominent historian like Richard Hofstadter “offered a bizarre alchemy: the roots of McCarthyism... were to be found in the very populism that he and others had praised before the Red Scare.” This despite the fact that the aims of the Wisconsin Republican Senator Joseph McCarthy were entirely at odds with those of the 19th-century party.

Whether your interest in American politics lies primarily in the past or the present, your time will be well spent with this book that packs so much information in so relatively few words.

Pity the poor Populists—or the memory thereof. If those late-19th century American radical democrats were to have imagined if and how they might be remembered in the third millennium, “little to not-at-all” might have seemed a reasonable expectation. But certainly they would have been shocked to find the word “populist” applied to a future president who flaunted, and even exaggerated, his wealth, when what they were all about was challenging the out-of-control wealth and power of the “Robber Barons” of their day, to the end of democratizing their grip on the nation economy.

And they would have likely been horrified by the likes of a recent New York Times Magazine article, “The President, the Soccer Hooligans, and an Underworld ‘House of Horrors,’” in which Robert F. Worth speaks of Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban’s hope that admitting Serbia to the European Union could help “steer the European Club in a more populist and less democratic direction.”

No doubt they would have asked if there was not someone who would set the record straight. As Steve Babson—who has set himself the task of doing just that in Forgotten Populists: When Farmers Turned Left to Save Democracy—writes, “The People’s Party of 1892 was the only substantial movement in U.S. history to actually call itself Populist,” whereas, “the label currently serves as a sly pejorative, hinting at the unreliable behavior and hidden agenda of anyone who challenges established authority”—and, as we see above, maybe not just hinting.

The Alliance/Populist era saw the emergence of that distinctively American debate, in which the representatives of the monied class denounce their opponents as socialists, while the representatives of the working classes deny that their ideas are socialistic—rather than acknowledging that many elements of their program would indeed involve greater democratic control of the economy—because in the United States, the idea is deemed beyond the pale.

The actual historical Populists were of an age when farmers constituted 40% of the American workforce, compared to 2% today (Babson notes that Bill Gates is now “the nation’s largest private farm owner”), while new technologies were facilitating the concentration of previously unimaginable wealth in the hands of a few gentlemen who more than matched the recent White House resident in their conviction that their wealth was a good thing not only for themselves, but for the entire nation.

As the book recounts, John D. Rockefeller, whose wealth came from oil, would declare that “God gave me my money,” while stock speculator and railroad owner Jay Gould told the U.S. Senate that “We have made the country rich... We have developed the country.” Steel magnate Andrew Carnegie, who would become famously responsible for the armed repression of the 1892 Homestead Steel strike, nonetheless predicted a future “reign of harmony,” characterized by the beneficent philanthropy of members of his class who would spend this money far more wisely than the public “would or could have done for itself.”

The Populists grew out of the Farmers’ Alliance and Cooperative Union that spread from Texas in the 1870s. By 1890, its membership, Babson writes, “had swelled well beyond one million, including not only debt-burdened farmers, but a wide range of allies in small towns and villages who were also struggling with poverty and economic insecurity.” Many of the estimated upwards-of-10,000 local chapters, or “sub-Alliances” that sprouted throughout the South were religiously oriented, generally of the “Social Christian” variety. Perhaps as many as a quarter of a million women were involved. Racial politics reflected the regions, with the Northern Alliance open to Black and white, while separate Southern and Colored Alliances operated in the south, the latter under far more restricted parameters.

Generally sharing the common goal of a “Cooperative Commonwealth” of the producing classes with organizations such as the Knights of Labor—the nation’s earliest mass union—and the still-existing Grange, along the way Alliance members put together more than 300 local cooperatives as vehicles for farmers to collectively sell their crops and purchase supplies. The owning classes responded by promptly closing their own ranks: Bankers refused loans to Cooperative Exchanges; manufacturers refused to sell to them; grain merchants and cotton buyers declined to buy from Alliance bundlers; regular merchants undersold cooperative stores in order to drive them under before returning to their previous uncompetitive prices.

Faced with the problem of insufficient capital that sinks so many cooperative organizations, the Alliances decided that if the federal government could provide the railroad barons with free land to build railroads on which they could then overcharge the farmer for shipping his goods, it could just as well build public warehouses—which they called “subtreasuries”—where farmers could store their crop, thereby avoiding the type of harvest-time glut that typically forced them to sell their produce below its value.

In 1890, the Kansas Alliance stunned the nation by taking to the ballot and sending five of its people to Congress and winning control of the state legislature; Nebraska had similar success.

Two years later, the effort went national with the formation of the People’s Party that would take 50 Congressional seats in 16 states, along with seven governorships. James Weaver, the party’s presidential nominee, carried five states—becoming the only “third party” candidate to win Electoral College votes during the entire period between the Civil War and former president Theodore Roosevelt’s 1912 “Bullmoose” campaign. And yet his vote amounted to less than 9% of the nationwide total, the party proving unable to truly go national in such a brief time.

Author Steve Babson (n.b., a longtime friend of this reviewer) is the author or co-author of six previous books, serious history all, a background reflected in this book’s overall careful presentation and assessment. In considering both the degree to which successful collaboration between white and Black Populists exceeded the norm of the time, as well as the instances of failure to buck that norm when called for, he cites Martin Luther King’s judgement that the Populists “began uniting the Negro and white masses into a voting block that threatened to drive the Bourbon interests from the command posts of political power.”

But with this book, Babson also reaches back to deeper roots, in Popular Economic Press, the rubric under which he and illustrator and wife Nancy Brigham produced the 1973, Why Do We Spend so Much Money? Like that work, Forgotten Populists is large format, heavily illustrated, aimed at people who don’t already belong to the History Book Club, and meant to be of use in the current political fray.

Babson devotes particular attention to the question of how the word “populist” has degenerated from the reality of the actual Populists of the past into its current usage “to vilify rowdy commoners when they challenge favored elites.” The Alliance/Populist era saw the emergence of that distinctively American debate, in which the representatives of the monied class denounce their opponents as socialists, while the representatives of the working classes deny that their ideas are socialistic—rather than acknowledging that many elements of their program would indeed involve greater democratic control of the economy—because in the United States, the idea is deemed beyond the pale.

With a level of scholarship one might not expect to find in a publication aimed at such a general audience, Babson specifically traces the transformation of the word’s usage back to the days of the 1950s Red Scare era, when a prominent historian like Richard Hofstadter “offered a bizarre alchemy: the roots of McCarthyism... were to be found in the very populism that he and others had praised before the Red Scare.” This despite the fact that the aims of the Wisconsin Republican Senator Joseph McCarthy were entirely at odds with those of the 19th-century party.

Whether your interest in American politics lies primarily in the past or the present, your time will be well spent with this book that packs so much information in so relatively few words.