SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

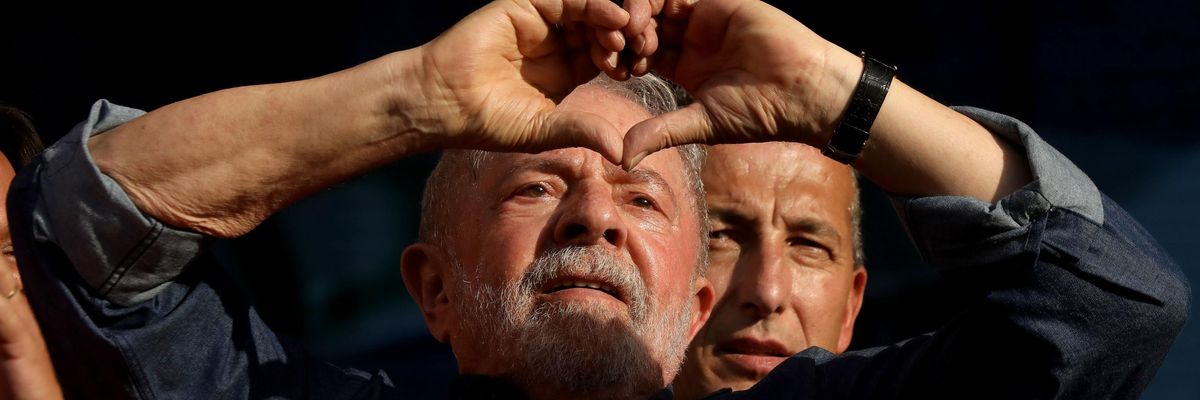

Brazilian presidential frontrunner Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva gestures during a demonstration on May 1, 2022 in Sao Paulo, Brazil.

They can see with fresh eyes the deeper democratic possibilities that many are seeking, an able government, a more responsive government.

When Americans think about Latin American politics the cliché images that may come to mind are of military coups, tanks rolling, and generals in sunglasses. If Americans hear news about current Latin American politics it usually will deal with democracies that have died or are under assault, as is the case in Venezuela, Nicaragua, and El Salvador. So informed, many Americans would find the idea that Latin America could teach the U.S. anything positive about democracy to be downright laughable.

But things have changed. Although there remain serious issues for Latin American democracies, it is nonetheless fair to say that most of Latin America is governed by emerging democracies these days.

Think of most democracies around the world as falling basically into one of two categories: old, tight, democracies and young, loose democracies.

Old democracies, especially like that in the United States, have institutions and rules that can make them hardy and more likely to endure, but this very resilience can function to make old democracies highly resistant to much-needed change.

Citizens of old democracies often confuse the elements of their own political system as the very essence and singular definition of democracy. In the U.S. that can mean concluding that a proper democracy must have a house and a senate, four-year presidential terms, a nine-member Supreme Court, along with all the other long-standing aspects of the American political system. To this view, any attempt to modify or update any of the time-honored institutions or customs would mean threating the very foundations of democracy itself.

The implication of this, however, is that old, tight democracies can become burdened with recalcitrant institutions and increasingly problematic political habits. Together these can render old, tight democracies incapable of reforming themselves, powerless to revitalize their democracy. Democracy can become buried under the rumble of centuries-old political deal-making, long-ago compromises of expediency that had only been intended to solve the impasses of those moments in time. In the U.S. this nearly always meant yielding to the demands of slave-holders, and after the Civil War, yielding to the demands of white southern racists seeking to keep Blacks disenfranchised, segregated, and threatened.

The resulting political system in old, tight democracies can become one that is permanently stuck, unable to carry out even the most basic political chores, such as passing a national budget. In this manner, old democracies can be slowly transformed into a democracy in name only, succeeding only in obstructing the democratic will of the majority of the electorate.

In the U.S. ossified institutions and practices–the electoral college; the filibuster rule in the senate; the allocation of senate seats favoring scant rural populations while grossly under-representing urban populations, especially people of color; the lifetime appointments to the Supreme Court without a mandatory retirement age–are not the very definition of democracy. Rather, they are the nation’s greatest hindrances to the realization of full democracy. Exasperated citizens look at this situation and may just opt out, the act of voting seen as at best, a waste of time, at worst, a tacit endorsement of a deeply dysfunctional and undemocratic political system.

But young loose democracies, like those found across Latin America, nearly all dating from the 1980s, are not so encumbered. No weight of long-established traditions stands in the way of change. Young, loose democracies are not nearly as hindered from making the changes that voters seek, steps to make their nation more democratic and governed more ably. These newer democracies are more fluid, the rules of governance more readily malleable. It is realistic in young, loose democracies to think of setting aside a constitution that is just not working and writing a new one, as happened in Ecuador in 2008 or in Bolivia in 2009. Significantly, the rules for approval of these new constitutions were established on the fly, just as they were in the case of the U.S. when it was once a young, loose democracy and was adopting its first and only constitution.

So it is today that these young democracies that can teach old democracies.

They can see with fresh eyes the deeper democratic possibilities that many are seeking, an able government, a more responsive government. What young, loose democracies can most remind us all is that democracy is perhaps our greatest human experiment, but one that must be continually recreated to reflect changing social realities, clearing away the wreckage from the past that can continually frustrate our current democratic aspirations.

Old tight democracies can come unglued in trying to meet the challenge of a novel and serious criminal challenge to the basic survival of democracy. Such a development seemed unthinkable in the U.S. until the coup attempt led by President Trump on January 6th after he lost the 2020 election. As he and others are now being called before the courts to face criminal trials for their actions, some supporters of the former president have seen these steps as illegitimate, the “weaponization of the criminal justice system,” the actions of a “banana republic.” This is a slur that most Latin Americans would have no trouble recognizing.

But Latin America’s democracies today actually provide examples of how to best meet the challenge of effectively holding former and current law-breaking leaders accountable. Former Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro is now barred from running for office for seven years due to his gross misuse of his official powers, including, among many alleged crimes, fomenting insurrection.

Odebrecht, the giant multinational construction firm, in 2016 admitted in U.S. court to paying out millions in hefty bribes to lawmakers all over the Americas. Nearly all of the many current and former Latin American leaders who took Odebrecht bribes are now either in prison or will soon be. It is precisely because these young democracies are more flexible in their rules, less burdened by the weight of tradition in their democracies, that they able to handle with greater adaptability and success the political stress test that has come up all around the Americas, dealing with a law-breaking current or former leader.

In bringing criminal charges against law-breaking leaders, Latin America is at long last honoring the rule of law, the principle of equality before the courts without exception. Indeed, the presence of an ongoing criminal case of a current or recent political leader should not be seen as evidence of the undermining of democracy, but instead provides proof that a nation is taking necessary if difficult steps to help assure democracy.

In calling former president Trump to account the U.S. is becoming more like Latin America, moving into alignment with hopeful hemispheric political trends. This is a good thing. If the United States is no longer the best example of and inspiration for democracy in the hemisphere, it still could be. One important way to do this would be unafraid to bring an ex-leader to justice.

Latin American nations will think no worse of us for this. In fact, they are getting very good at doing this themselves. The U.S. should look to their example.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

When Americans think about Latin American politics the cliché images that may come to mind are of military coups, tanks rolling, and generals in sunglasses. If Americans hear news about current Latin American politics it usually will deal with democracies that have died or are under assault, as is the case in Venezuela, Nicaragua, and El Salvador. So informed, many Americans would find the idea that Latin America could teach the U.S. anything positive about democracy to be downright laughable.

But things have changed. Although there remain serious issues for Latin American democracies, it is nonetheless fair to say that most of Latin America is governed by emerging democracies these days.

Think of most democracies around the world as falling basically into one of two categories: old, tight, democracies and young, loose democracies.

Old democracies, especially like that in the United States, have institutions and rules that can make them hardy and more likely to endure, but this very resilience can function to make old democracies highly resistant to much-needed change.

Citizens of old democracies often confuse the elements of their own political system as the very essence and singular definition of democracy. In the U.S. that can mean concluding that a proper democracy must have a house and a senate, four-year presidential terms, a nine-member Supreme Court, along with all the other long-standing aspects of the American political system. To this view, any attempt to modify or update any of the time-honored institutions or customs would mean threating the very foundations of democracy itself.

The implication of this, however, is that old, tight democracies can become burdened with recalcitrant institutions and increasingly problematic political habits. Together these can render old, tight democracies incapable of reforming themselves, powerless to revitalize their democracy. Democracy can become buried under the rumble of centuries-old political deal-making, long-ago compromises of expediency that had only been intended to solve the impasses of those moments in time. In the U.S. this nearly always meant yielding to the demands of slave-holders, and after the Civil War, yielding to the demands of white southern racists seeking to keep Blacks disenfranchised, segregated, and threatened.

The resulting political system in old, tight democracies can become one that is permanently stuck, unable to carry out even the most basic political chores, such as passing a national budget. In this manner, old democracies can be slowly transformed into a democracy in name only, succeeding only in obstructing the democratic will of the majority of the electorate.

In the U.S. ossified institutions and practices–the electoral college; the filibuster rule in the senate; the allocation of senate seats favoring scant rural populations while grossly under-representing urban populations, especially people of color; the lifetime appointments to the Supreme Court without a mandatory retirement age–are not the very definition of democracy. Rather, they are the nation’s greatest hindrances to the realization of full democracy. Exasperated citizens look at this situation and may just opt out, the act of voting seen as at best, a waste of time, at worst, a tacit endorsement of a deeply dysfunctional and undemocratic political system.

But young loose democracies, like those found across Latin America, nearly all dating from the 1980s, are not so encumbered. No weight of long-established traditions stands in the way of change. Young, loose democracies are not nearly as hindered from making the changes that voters seek, steps to make their nation more democratic and governed more ably. These newer democracies are more fluid, the rules of governance more readily malleable. It is realistic in young, loose democracies to think of setting aside a constitution that is just not working and writing a new one, as happened in Ecuador in 2008 or in Bolivia in 2009. Significantly, the rules for approval of these new constitutions were established on the fly, just as they were in the case of the U.S. when it was once a young, loose democracy and was adopting its first and only constitution.

So it is today that these young democracies that can teach old democracies.

They can see with fresh eyes the deeper democratic possibilities that many are seeking, an able government, a more responsive government. What young, loose democracies can most remind us all is that democracy is perhaps our greatest human experiment, but one that must be continually recreated to reflect changing social realities, clearing away the wreckage from the past that can continually frustrate our current democratic aspirations.

Old tight democracies can come unglued in trying to meet the challenge of a novel and serious criminal challenge to the basic survival of democracy. Such a development seemed unthinkable in the U.S. until the coup attempt led by President Trump on January 6th after he lost the 2020 election. As he and others are now being called before the courts to face criminal trials for their actions, some supporters of the former president have seen these steps as illegitimate, the “weaponization of the criminal justice system,” the actions of a “banana republic.” This is a slur that most Latin Americans would have no trouble recognizing.

But Latin America’s democracies today actually provide examples of how to best meet the challenge of effectively holding former and current law-breaking leaders accountable. Former Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro is now barred from running for office for seven years due to his gross misuse of his official powers, including, among many alleged crimes, fomenting insurrection.

Odebrecht, the giant multinational construction firm, in 2016 admitted in U.S. court to paying out millions in hefty bribes to lawmakers all over the Americas. Nearly all of the many current and former Latin American leaders who took Odebrecht bribes are now either in prison or will soon be. It is precisely because these young democracies are more flexible in their rules, less burdened by the weight of tradition in their democracies, that they able to handle with greater adaptability and success the political stress test that has come up all around the Americas, dealing with a law-breaking current or former leader.

In bringing criminal charges against law-breaking leaders, Latin America is at long last honoring the rule of law, the principle of equality before the courts without exception. Indeed, the presence of an ongoing criminal case of a current or recent political leader should not be seen as evidence of the undermining of democracy, but instead provides proof that a nation is taking necessary if difficult steps to help assure democracy.

In calling former president Trump to account the U.S. is becoming more like Latin America, moving into alignment with hopeful hemispheric political trends. This is a good thing. If the United States is no longer the best example of and inspiration for democracy in the hemisphere, it still could be. One important way to do this would be unafraid to bring an ex-leader to justice.

Latin American nations will think no worse of us for this. In fact, they are getting very good at doing this themselves. The U.S. should look to their example.

When Americans think about Latin American politics the cliché images that may come to mind are of military coups, tanks rolling, and generals in sunglasses. If Americans hear news about current Latin American politics it usually will deal with democracies that have died or are under assault, as is the case in Venezuela, Nicaragua, and El Salvador. So informed, many Americans would find the idea that Latin America could teach the U.S. anything positive about democracy to be downright laughable.

But things have changed. Although there remain serious issues for Latin American democracies, it is nonetheless fair to say that most of Latin America is governed by emerging democracies these days.

Think of most democracies around the world as falling basically into one of two categories: old, tight, democracies and young, loose democracies.

Old democracies, especially like that in the United States, have institutions and rules that can make them hardy and more likely to endure, but this very resilience can function to make old democracies highly resistant to much-needed change.

Citizens of old democracies often confuse the elements of their own political system as the very essence and singular definition of democracy. In the U.S. that can mean concluding that a proper democracy must have a house and a senate, four-year presidential terms, a nine-member Supreme Court, along with all the other long-standing aspects of the American political system. To this view, any attempt to modify or update any of the time-honored institutions or customs would mean threating the very foundations of democracy itself.

The implication of this, however, is that old, tight democracies can become burdened with recalcitrant institutions and increasingly problematic political habits. Together these can render old, tight democracies incapable of reforming themselves, powerless to revitalize their democracy. Democracy can become buried under the rumble of centuries-old political deal-making, long-ago compromises of expediency that had only been intended to solve the impasses of those moments in time. In the U.S. this nearly always meant yielding to the demands of slave-holders, and after the Civil War, yielding to the demands of white southern racists seeking to keep Blacks disenfranchised, segregated, and threatened.

The resulting political system in old, tight democracies can become one that is permanently stuck, unable to carry out even the most basic political chores, such as passing a national budget. In this manner, old democracies can be slowly transformed into a democracy in name only, succeeding only in obstructing the democratic will of the majority of the electorate.

In the U.S. ossified institutions and practices–the electoral college; the filibuster rule in the senate; the allocation of senate seats favoring scant rural populations while grossly under-representing urban populations, especially people of color; the lifetime appointments to the Supreme Court without a mandatory retirement age–are not the very definition of democracy. Rather, they are the nation’s greatest hindrances to the realization of full democracy. Exasperated citizens look at this situation and may just opt out, the act of voting seen as at best, a waste of time, at worst, a tacit endorsement of a deeply dysfunctional and undemocratic political system.

But young loose democracies, like those found across Latin America, nearly all dating from the 1980s, are not so encumbered. No weight of long-established traditions stands in the way of change. Young, loose democracies are not nearly as hindered from making the changes that voters seek, steps to make their nation more democratic and governed more ably. These newer democracies are more fluid, the rules of governance more readily malleable. It is realistic in young, loose democracies to think of setting aside a constitution that is just not working and writing a new one, as happened in Ecuador in 2008 or in Bolivia in 2009. Significantly, the rules for approval of these new constitutions were established on the fly, just as they were in the case of the U.S. when it was once a young, loose democracy and was adopting its first and only constitution.

So it is today that these young democracies that can teach old democracies.

They can see with fresh eyes the deeper democratic possibilities that many are seeking, an able government, a more responsive government. What young, loose democracies can most remind us all is that democracy is perhaps our greatest human experiment, but one that must be continually recreated to reflect changing social realities, clearing away the wreckage from the past that can continually frustrate our current democratic aspirations.

Old tight democracies can come unglued in trying to meet the challenge of a novel and serious criminal challenge to the basic survival of democracy. Such a development seemed unthinkable in the U.S. until the coup attempt led by President Trump on January 6th after he lost the 2020 election. As he and others are now being called before the courts to face criminal trials for their actions, some supporters of the former president have seen these steps as illegitimate, the “weaponization of the criminal justice system,” the actions of a “banana republic.” This is a slur that most Latin Americans would have no trouble recognizing.

But Latin America’s democracies today actually provide examples of how to best meet the challenge of effectively holding former and current law-breaking leaders accountable. Former Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro is now barred from running for office for seven years due to his gross misuse of his official powers, including, among many alleged crimes, fomenting insurrection.

Odebrecht, the giant multinational construction firm, in 2016 admitted in U.S. court to paying out millions in hefty bribes to lawmakers all over the Americas. Nearly all of the many current and former Latin American leaders who took Odebrecht bribes are now either in prison or will soon be. It is precisely because these young democracies are more flexible in their rules, less burdened by the weight of tradition in their democracies, that they able to handle with greater adaptability and success the political stress test that has come up all around the Americas, dealing with a law-breaking current or former leader.

In bringing criminal charges against law-breaking leaders, Latin America is at long last honoring the rule of law, the principle of equality before the courts without exception. Indeed, the presence of an ongoing criminal case of a current or recent political leader should not be seen as evidence of the undermining of democracy, but instead provides proof that a nation is taking necessary if difficult steps to help assure democracy.

In calling former president Trump to account the U.S. is becoming more like Latin America, moving into alignment with hopeful hemispheric political trends. This is a good thing. If the United States is no longer the best example of and inspiration for democracy in the hemisphere, it still could be. One important way to do this would be unafraid to bring an ex-leader to justice.

Latin American nations will think no worse of us for this. In fact, they are getting very good at doing this themselves. The U.S. should look to their example.