SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

"As usual, President Trump appears more concerned with buoying business interests than reforming our broken system to deliver safe, affordable food," one advocate said.

In her confirmation hearing before the U.S. Senate on Thursday, President Donald Trump's agriculture secretary nominee Brooke Rollins expressed support for the mass deportation of undocumented immigrants, work requirements for federal food aid, and a law that would prohibit states from passing independent regulations of agricultural products.

Her testimony sparked concern from food justice and sustainable agriculture advocates, who said her lack of agricultural experience and pro-corporate worldview would harm farmworkers, animals, public health, and families in need.

"Rollins, as secretary of agriculture, will be a serious setback for farmers, ranchers, and rural communities already burdened by extreme weather events; livestock disease outbreaks; challenges in accessing land, capital, and new markets; food insecure families who rely on federal assistance to reach their nutritional needs; and for small and family farms being squeezed out by powerful food and agriculture corporations," Nichelle Harriott, policy director at Health, Environment, Agriculture, Labor (HEAL) Food Alliance, said in a statement.

"Her history demonstrates a disregard for and lack of commitment to supporting Black, Indigenous, and other farmers and ranchers of color, as well as small and family farmers, farmworkers, and the working people who sustain our food system."

Rollins, who testified before the Senate Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry at 10:00 am Eastern Time on Thursday, was a surprise choice to lead the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) for many agricultural groups as well as other members of the Trump team. While she grew up on a farm in Texas, participated in the 4-H and Future Farmers of America, and earned a bachelor's degree in agricultural development from Texas A&M University in 1994, her career diverged from the agricultural world once she graduated from the University of Texas School of Law. She worked for then-Texas Gov. Rick Perry, served under the first Trump administration in the White House Office of American Innovation and then as acting director of the U.S. Domestic Policy Council, and co-founded the right-wing America First Policy Institute think tank after 2020.

"Essentially, in more than three decades, Rollins has never had a job solely focused on food and agriculture policy," Karen Perry Stillerman, director in the Food and Environment Program at the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS), wrote in a blog post ahead of Rollins' hearing.

One statement that particularly concerned food and agriculture justice campaigners was Rollins' support for the Ending Agricultural Trade Suppression (EATS) Act. This act would repeal California's Proposition 12, which bans the sale in the state of pork, veal, or eggs from animals "confined in a cruel manner." It would also prevent other states from passing similar laws and is backed by agribusiness lobby firms like the National Cattlemen's Beef Association, the National Pork Producers Council, and the Farm Bureau.

"Brooke Rollins is a well established Trump loyalist, ready to bow to corporate interests on Day One. Her endorsement of the EATS Act signals the dangerous pro-corporate agenda she appears ready to bring USDA, if confirmed to lead the key agency," Food & Water Watch senior food policy analyst Rebecca Wolf said in a statement.

"The USDA has massive leverage in shaping our food system, but, as usual, President Trump appears more concerned with buoying business interests than reforming our broken system to deliver safe, affordable food," Wolf continued. "Congress must stand up to Trump's corporate cronies and their dangerous legislation. That means stopping the EATS Act, which threatens to exacerbate consolidation in the agriculture sector and drive an archaic race to the bottom in which consumers, animals, and our environment lose out to enormous profit-grubbing corporations."

During the hearing, senators questioned Rollins on how her USDA would handle key aspects of Trump's agenda that are likely to impact farmers. His planned 25% tariffs on China, Mexico, and Canada could lead to retaliation from those countries that would block U.S. access to their markets, as happened with China in 2018.

Rollins said that the administration was prepared to give aid to farmers as it did during Trump's first term.

"What we've heard from our farmers and ranchers over and over again is they want to be able to do the work. They want to be able to export. They don't want to solve this problem by getting aid," Sen. Michael Bennet (D-Colo.) responded.

Rollins answered that she would also work to expand access to agricultural markets.

Sen. Dick Durbin (D-Ill.), meanwhile, raised the question of how Trump's USDA would respond to his plan to deport millions of undocumented immigrants, given that around 40% of U.S. farmworkers are undocumented.

"The president's vision of a secure border and a mass deportation at a scale that matters is something I support," Rollins answered. "My commitment is to help President Trump deploy his agenda in an effective way, while at the same time defending, if confirmed secretary of agriculture, our farmers and ranchers across this country... And so having both of those, which you may argue is in conflict, but having both of those is key priorities."

Another major policy area that Rollins would oversee as agriculture secretary is the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), formerly referred to as food stamps. SNAP makes up the bulk of federal spending in the Farm Bill, which has been delayed as Congress debates both nutrition and work requirements for the program, according toThe Texas Tribune. While most SNAP recipients are already required to work unless they have child- or eldercare responsibilities, lawmakers are debating stricter requirements.

Rollins told senators that she thought work requirements were "important."

In her pre-hearing article, UCS's Stillerman also expressed concerns about Rollins' history of climate denial and marriage to the president of an oil exploration company.

"In 2018, then-White House aide Rollins told participants at a right-wing energy conference that 'we know the research of CO2 being a pollutant is just not valid'—a perspective that is extreme even in the Trump era," she wrote.

Further, Stillerman noted Rollins' history of repeating "hateful and dangerous conspiracy theories," in particular about Democrats, left-wing organizations, and movements for women's and Black rights.

"Given her apparent antipathy for social justice movements, I have to wonder what Rollins thinks about the 66 recommendations made in early 2024 by the USDA Equity Commission to address a long history of racial discrimination and level the playing field for farmers of all kinds," Stillerman wrote.

After the hearing, Harriott of HEAL Food Alliance said: "Our food and farming communities deserve leadership that champions the needs of everyone, regardless of where we live or what we look like. The next secretary of agriculture must ensure that all farmers, ranchers, farmworkers, and food system workers have the resources they need to thrive."

"Unfortunately, despite her testimony today, Brooke Rollins lacks the agricultural expertise required to effectively lead the USDA. Her history demonstrates a disregard for and lack of commitment to supporting Black, Indigenous, and other farmers and ranchers of color, as well as small and family farmers, farmworkers, and the working people who sustain our food system," Harriott continued.

In the case that Rollins is confirmed, Harriott called on her to "prioritize disaster relief for farmers facing climate-related disruptions; invest in small farms and those practicing traditional, cultural, and ecological farming methods; ensure protections for food and farmworkers; and safeguard vital nutrition programs like SNAP to reduce hunger nationwide."

For agriculture as with energy, the real climate solutions are being silenced by the corporate cacophony.

I remember being filled with excitement when the Paris agreement to limit global warming to 1.5°C was adopted by nearly 200 countries at COP21. But after the curtains closed on COP29 last month—almost a decade later—my disenchantment with the event reached a new high.

As early as the 2010s, scientists from academia and the United Nations Environment Program warned that the U.S. and Europe must cut meat consumption by 50% to avoid climate disaster. Earlier COPs had mainly focused on fossil fuels, but meat and dairy corporations undoubtedly saw the writing on the wall that they too would soon come under fire.

Our food system needs to be sustainable for all—people, animals, and our planet.

Animal agriculture accounts for at least 14.5% of global greenhouse gas emissions, over quadruple the amount from global aviation. Global meat and dairy production have increased almost fivefold since the 1960s with the advent of industrialized agriculture. These factory-like systems are characterized by cramming thousands of animals into buildings or feedlots and feeding them unnatural grain diets from crops grown offsite. Even if all fossil fuel use was halted immediately, we would still exceed 1.5°C temperature rise without changing our food system, particularly our production and consumption of animal-sourced foods.

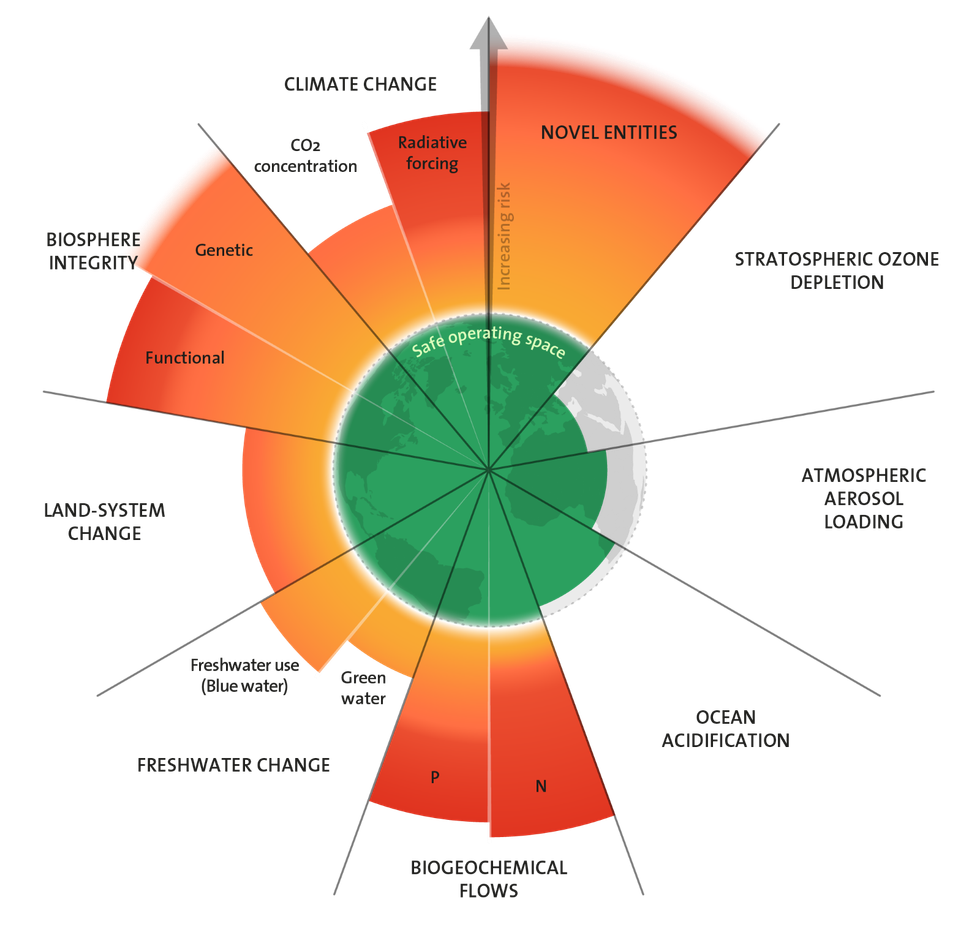

But climate change is just one of the threats we face. We have also breached five other planetary boundaries—biodiversity; land-use change; phosphorus and nitrogen cycling; freshwater use; and pollution from man-made substances such as plastics, antibiotics, and pesticides—all of which are also driven mainly by animal-sourced food production.

By the time world leaders were ready to consider our food system's impact on climate and the environment, the industrialized meat and dairy sector had already prepared its playbook to maintain the status quo. The Conference of Parties is meant to bring together the world's nations and thought leaders to address climate change. However, the event has become increasingly infiltrated by corporate interests. There were 52 delegates from the meat and dairy sector at COP29, many with country badges that gave them privileged access to diplomatic negotiations.

In this forum and others, the industry has peddled bombastic "solutions" under the guise of technology and innovation. Corporate-backed university research has lauded adding seaweed to cattle feed and turning manure lagoons the size of football fields into energy sources to reduce methane production. In Asia, companies are putting pigs in buildings over 20 stories tall, claiming the skyscrapers cut down on space and disease risks. And more recently, Bill Gates and Jeff Bezos started bankrolling research and development into vaccines that reduce the methane-causing bacteria found naturally in cows' stomachs. The industry hopes that the novelty and allure of new technologies will woo lawmakers and investors, but these "solutions" create more problems than they solve, exacerbating net greenhouse gas emissions, air and water pollution, wildlife loss, and freshwater depletion.

Emissions from animal-sourced foods can be broadly divided into four categories: ruminant fermentation (cow burps); manure; logistics (transport, packaging, processing, etc.); and land-use change, i.e., the conversion of wild spaces into pasture, feedlots, and cropland for feed. In the U.S., ruminant fermentation and manure emit more methane than natural gas and petroleum systems combined.

A new report found that beef consumption must decline by over a quarter globally by 2035 to curb methane emissions from cattle, which the industry's solutions claim to solve without needing to reduce consumption. But the direct emissions from cattle aren't the only problem—beef and dairy production is also the leading driver of deforestation, which must decline by 72% by 2035, and reforestation must rise by 115%. About 35% of habitable land is used to raise animals for food or to grow their feed (mostly corn and soy), about the size of North and South America combined.

Put simply, the inadequate solutions put forth by Big Ag cannot outpace industrialized farming's negative impacts on the planet. While seaweed and methane vaccines may address cow burps, they don't address carbon emissions from deforestation or manure emissions of nitrous oxide, a greenhouse gas over 270 times more powerful than CO2. They also don't address the nitrate water pollution from manure, which can sicken people and cause massive fish kills and harmful algal blooms; biodiversity decline from habitat loss, which has dropped 73% since the rise of industrialized animal agriculture; freshwater use, drying up rivers and accounting for over a quarter of humanity's water footprint; or pesticide use on corn and soy feed, which kills soil microorganisms that are vital to life on Earth.

Skyscrapers, while solving some land-use change, do not consider the resources and the land used to grow animal feed, which is globally about equivalent to the size of Europe. They also don't address the inherent inefficiencies with feeding grain to animals raised for food. If fed directly to people, those grains could feed almost half the world's population. And while the companies using pig skyscrapers claim they enhance biosecurity by keeping potential viruses locked inside, a system failure could spell disaster, posing a bigger threat to wildlife and even humans.

We need both a monumental shift from industrialized agriculture to regenerative systems and a dramatic shift from animal-heavy diets to diets rich in legumes, beans, vegetables, fruits, and whole grains, with meat and dairy as a specialty rather than a staple.

One solution that is gaining traction as an alternative to Big Ag's proposals is regenerative grazing. When done right, regenerative grazing eliminates the need for pesticides and leans into the natural local ecology, putting farm animals onto rotated pastures and facilitating carbon uptake into the soil. Regenerative animal agriculture is arguably the only solution put forward that addresses all six breached planetary boundaries as well as animal welfare and disease risk, and studies suggest it can improve the nutritional quality of animal-sourced foods. While it is imperative to transition from industrialized to regenerative systems, regenerative grazing comes with major caveats. This type of farming is only beneficial in small doses—cutting down centuries-old forests or filling in carbon-rich wetlands to make way for regenerative pastures would do much more climate and ecological harm than good. Soil carbon sequestration takes time and increases with vegetation and undisturbed soil, meaning that any regenerative pastures made today will never be able to capture as much carbon as the original natural landscape, especially in forests, mangroves, wetlands, and tundra. And while regenerative farmlands create better wildlife habitats than feedlots and monocultures, they still don't function like a fully natural ecosystem and food web. Also, cattle emit more methane than their native ruminant counterparts such as bison and deer.

Most notably, however, we simply don't have enough land to produce regeneratively raised animal products at the current consumption rate. Regenerative grazing requires more land than industrialized systems, sometimes two to three times more, and as mentioned the livestock industry already occupies over one-third of the world's habitable land. In all, we have much more to gain from rewilding crop- and rangeland than from turning the world into one big regenerative pasture.

All this brings us to one conclusion—the one that was made by scientists over a decade ago: We need to eat less meat. As Action Aid's Teresa Anderson noted at this year's COP, "The real answers to the climate crisis aren’t being heard over the corporate cacophony."

Scientific climate analyses over the last few years have been grim at best, and apocalyptic at worst. According to one of the latest U.N. reports, limiting global temperature rise to 1.5°C (2.7°F) requires cutting greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 57% by 2035, relative to 2023 emissions. However, current national policies—none of which currently include diet shifts—will achieve less than a 1% reduction by 2035. If the 54 wealthiest nations adopted sustainable healthy diets with modest amounts of animal products, they could slash their total emissions by 61%. If we also allowed the leftover land to rewild, we could sequester 30% of our global carbon budget in these nations and nearly 100% if adopted globally.

Our food system needs to be sustainable for all—people, animals, and our planet. Quick fixes and bandages will not save our planet from climate change, biodiversity loss, and pollution. We need both a monumental shift from industrialized agriculture to regenerative systems and a dramatic shift from animal-heavy diets to diets rich in legumes, beans, vegetables, fruits, and whole grains, with meat and dairy as a specialty rather than a staple. As nations draft their policies for COP30, due early this year, we need leaders to adopt real food system solutions instead of buying into the corporate cacophony.

"Trade agreements should not allow multinational pesticide and biotech companies to imperil the health of people and the environment," one campaigner said.

A trade dispute panel under the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement ruled on Friday that Mexico violated the trade accord with its ban on genetically modified corn for human consumption.

The decision was a win for the agribusiness industry and the Biden administration, which called for the panel in August of last year after negotiations with the Mexican government failed. However, civil society groups condemned the ruling, saying it overlooked threats to the environment, public health, and Indigenous rights while overstating potential harm to U.S. corn exporters.

"The panel ignores the mountains of peer-reviewed evidence Mexico presented on the risks to public health and the environment of genetically modified (GM) corn and glyphosate residues for people in Mexico who consume more than 10 times the corn as we do in the U.S. and do so not in processed foods but in minimally processed forms such as tortillas," Timothy A. Wise, an investigative journalist with U.S. Right to Know, told Common Dreams. "Mexico's precautionary policies are indeed well-grounded in science, and the U.S. and the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) have no business using a trade agreement to undermine a domestic policy that barely affects trade between the two countries."

"This ruling will make winners out of agrochemical corporations and losers out of everyone else."

Then-Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) first announced a ban on GM corn and glyphosate in 2020, to go into effect by 2024. This was then amended in February 2023 to scratch the 2024 deadline for animal feed and industrial uses of corn, but immediate ban GM corn for tortillas and tortilla dough. While the deleted deadline was widely seen as a concession to pressure from the Biden administration, the U.S. still went ahead with challenging the rule under the USMCA.

In response to Friday's decision, U.S. Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack commended the panel for affirming that "Mexico's approach to biotechnology was not based on scientific principles or international standards."

"Mexico's measures ran counter to decades' worth of evidence demonstrating the safety of agricultural biotechnology, underpinned by science- and risk-based regulatory review systems," Vilsack continued. "This decision ensures that U.S. producers and exporters will continue to have full and fair access to the Mexican market, and is a victory for fair, open, and science- and rules-based trade, which serves as the foundation of the USMCA as it was agreed to by all parties."

Yet several U.S. environmental groups backed Mexico's case and said the science used by the U.S. to establish the safety of GM corn was out-of-date and insufficient. For example, the U.S. relies on studies from when GM or genetically engineered corn was first introduced to the market and does not account for how pesticides and herbicides are currently used on the corn.

"Trade agreements should not allow multinational pesticide and biotech companies to imperil the health of people and the environment," said Kendra Klein, PhD, deputy director of science at Friends of the Earth U.S. "The science is clear that GMO corn raises serious health concerns and that production of GMO corn depends on intensive use of the toxic weedkiller glyphosate."

Mily Treviño-Sauceda, the executive director of the Alianza Nacional de Campesinas, condemned Friday's decision.

"Mexico's policies to ban the use of GM corn and glyphosate were enacted to protect biodiversity, cultural heritage, and the rights of Indigenous people," Treviño-Sauceda said. "This decision will continue to adversely impact the quality and nutritional value of food reaching Mexican households. This is just another step in the direction of consolidating agricultural power to the U.S. agro-industrial complex that we will continue to challenge until we see real change for the benefit of the public and our health."

Other trade justice and agricultural advocates said the decision was a missed opportunity to transform trade and food systems beyond Mexico.

"The USMCA was hailed as a new kind of trade agreement, taking some steps forward on issues like labor rights and investment," said Karen Hansen-Kuhn, director of trade and international strategies at the Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy. "This dispute shows how far we still need to go. Mexico has every right to try to transform its food system to better feed its people and enhance rural livelihoods and biodiversity. The U.S. was wrong to challenge that initiative, and the panel is wrong to back them up"

Farm Action President Angela Huffman added: "We are disappointed in the panel's ruling today, which shows the U.S. successfully wielded its power on behalf of the world's largest agrochemical corporations to force their industrial technology onto Mexico. Mexico's ban GM corn and glyphosate presented a tremendous premium market opportunity for non-GM corn producers in the U.S. Instead of helping U.S. farmers transition to non-GM corn production, our government has continued to force GM corn onto people who don't want it and propped up agrochemical corporations based in other countries—such as Germany's Bayer and China's Syngenta. This ruling will make winners out of agrochemical corporations and losers out of everyone else."

Business interests, on the other hand, reacted positively to the news.

"This is the clearest of signals that upholding free-trade agreements delivers the stability needed for innovation to flourish and to anchor our food security," Emily Rees, president of plant-science industry group CropLife International, said, as Reutersreported.

The president of the U.S. National Corn Growers Association, Kenneth Hartman Jr., also celebrated the news, saying, "This outcome is a direct result of the advocacy efforts of corn grower leaders from across the country," according toThe Associated Press.

The Mexican government said it disagreed with the decision, but would abide by the panel's ruling.

"The Mexican government does not agree with the panel's finding, given that it considers that the measures in question are aligned with the principles of protecting public health and the rights of Indigenous communities," the country's Economy Department said. "Nonetheless, the Mexican government will respect the ruling."

The decision comes as U.S. President-elect Donald Trump has threatened to set a 25% tariff on all imports to the U.S. from Mexico and Canada unless the two countries decrease the number of migrants and the amount of fentanyl that enters the U.S. via their borders. As this would likely violate the USCMA, it puts additional pressure on Mexico to abide by the agreement in order to reinforce norms against Trump's challenge.

Wise criticized the panel for ruling against Mexico when real threats to trade governance loom on the horizon.

"At a time when the U.S. president-elect is threatening to levy massive tariffs on Mexican products, a blatant violation of the North American trade agreement, it is outrageous that a trade tribunal ruled in favor of the U.S. complaint against Mexico's limited restrictions on genetically modified corn, which barely affect U.S. exporters," Wise said in a statement.