With Bird Flu, Our Factory Farmed Chickens Have Come Home to Roost

It was only a matter of time before the horrific and unjust conditions in the animal agriculture system became the proving ground for a pathogen capable of igniting a dangerous pandemic. Now our luck may have run out.

In Albert Camus’ novel, The Plague, set in the French Algerian town of Oran, rats one day begin showing up dead on residents’ doorsteps, dying with violent spasms and blood pouring from their mouths.

At first, the rats’ death agonies are only a curiosity to the townspeople. But then the rats begin dying in greater numbers, their corpses piling up in the streets. “The staircase from the cellar to the attics was strewn with dead rats, 10 or a dozen of them. The garbage bins of all the houses in the street were full of rats.”

When Dr. Rieux, a physician, remarks upon the strange phenomenon to his mother, she replies vaguely, “It’s like that sometimes.”

The avian flu threat, however, has now given us an opportunity to rethink our existential and ethical relations with the other animals of our planet, and to recognize how closely our fates are bound together.

By the time Rieux realizes what is happening, it is too late. Bubonic plague has come to Oran. Soon it is the townspeople themselves who are dying in agony, their bodies heaping up in mounds—like the rats whose suffering, and fates, they had only days before viewed with indifference...

Lately, I have been thinking of Camus’ novel, as we ourselves teeter on the brink of a new deadly plague—avian flu. Like the people in the story, we too have remained indifferent to the suffering, and shared collective fate, of our fellow creatures. And we continue to do so at our own peril.

For more than a year, I have followed news reports of the H5N1 virus that causes bird flu, or highly pathogenic avian influenza, as it has torn across the world, infecting hundreds of species and killing millions of animals, from storks and snowy owls to cranes and harbor seals, from foxes and herons to finches and lions. Geese have fallen from the skies dead over Kansas City. House cats have died from violent seizures in Iceland and Texas. The virus has decimated colonies of Adélie penguins in Antarctica, wiped out albatross fledglings on the remote South African island of Marion, killed dolphins and manatees off the Florida coast.

Never have scientists seen a virus infect so many species all at once, nor spread so quickly or with such devastating effect. It is the first observed panzootic—a pandemic of “all” animals. Researchers are now calling avian flu an “existential threat” to planetary biodiversity.

While droves of our fellow beings were dying in agony in far-away places, however, few people seemed to notice or care. Even today, we resist acknowledging our own role in the catastrophe—the fact that it is we ourselves, by imprisoning billions of animals in the food system, then allowing the virus to run rampant inside it, who have turned H5N1 into a trans-species bioweapon. And now that bioweapon is turning toward us.

While the H5N1 virus is naturally occurring, it emerged as a global problem only when it became concentrated in the Asian poultry industry in the late 1990s. Farmers at the time killed hundreds of millions of chickens and other birds to try to contain the virus—in many cases, by burying them alive or setting them on fire. Since then, H5N1 has resurfaced again and again on animal farms, leading to the deaths of poultry and humans alike.

For years, epidemiologists have warned that the animal agriculture system was a time bomb waiting to go off. Most of the deadly diseases ever to have afflicted our own species, including cholera, smallpox, measles, tuberculosis, AIDS, and influenza, have been caused by our exploitation of animals for food. Today, three-quarters of all emerging infectious diseases are in fact zoonotic in origin—a consequence chiefly of the modern animal food system.

That system has increased our vulnerability to animal-borne diseases in two ways. First, raising cattle and other ruminants for slaughter requires staggering anounts of land, which destroys animal habitat and crowds species together, thus enabling viruses to find new hosts who lack natural immunity to them. (More than half the surface of the Earth has been turned into farmland, and 80% of that is devoted to raising animals for slaughter.) Second, we have created a permanent source of new plagues by concentrating sick and traumatized animals together in industrialized conditions.

Even with a vaccine, Americans can expect little help from their government should a bird flu pandemic materialize, since President Donald Trump is eviscerating the federal agencies responsible for public health and disease prevention.

Few people are aware of the sheer scale of the global animal food system. But each year, 80,000,000,000 land animals and up to 2,700,000,000,000 marine animals die violently to satisfy growing human demand for animal products. This system is now the most ecologically destructive force on our planet—the leading cause of the mass extinction crisis and the second-leading source of greenhouse gas emissions, as well as the main cause of freshwater system loss, algal blooms, and land degradation.

The animal food system is also a moral and epidemiological calamity. Billions of sensitive chickens, pigs, cows, and others are forced into miserable, fetid conditions of intensive confinement, where they are beaten, tormented with electric prods, and then brutally killed at a fraction of their lifespans. Our prisoners suffer such psychological and physiological stress and trauma that millions die even before they can reach a slaughterhouse. So to keep them alive, farmers pump them full of antibiotics. Seventy percent of antibiotics worldwide are fed to farmed animals, a practice which, in turn, is fueling deadly new strains of antibiotic-resistant “superbugs.”

Natural ecosystems constrain the virulence of pathogens like H5N1, by selecting out the most lethal traits that would otherwise keep a virus from spreading by killing its host prematurely. As science writer Brandon Keim observes, however, the “constraints on virulence” ordinarily found in nature are absent on industrialized poultry farms, where birds are killed at a tiny fraction of their normal lifespans. In fact, virulence is selected for.

It was only a matter of time, thus, before the horrific and unjust conditions in the animal agriculture system became the proving ground for a pathogen capable of igniting a dangerous pandemic. Now our luck may have run out.

Last year, the H5N1 virus crossed a crucial threshold, when wild birds exposed to concentrations of the virus on animal farms contracted the disease and spread it to other species along their migration routes. Meanwhile, the Biden administration, deferring to powerful agricultural interests—and seeking to avoid antagonizing rural voters in an election year—squandered every opportunity to track and contain the deadly disease. For months, the U.S. government effectively stood by and did nothing. As a result, H5N1 has now become endemic throughout the U.S. animal agriculture system. And the longer it remains there, the more likely is it to mutate into a form transmissable between humans.

How bad would that be? In 2005, David Nabarro, then the United Nations system coordinator for avian and human influenza, warned that a bird flu pandemic could kill up to 150 million people. That may be a conservative estimate, however, since the known past mortality rate from avian flu in humans has been over 50%, making H5N1 up to 100 times deadlier than Covid-19. Unlike Covid-19 furthermore, a bird flu pandemic would not primarily target older adults or people with underlying conditions, but would kill indiscriminately.

The H5N1 virus is neuropathic, meaning that it attacks the brain, causing conditions ranging from mild encaphalitis to seizures, coma, and death. Children and pregnant women would be especially vulnerable to the virus. When a Canadian teen contracted the H5N1 virus last year, she suffered multiple organ failure and had to be placed on a respirator for months before she recovered. Avian flu has meanwhile killed 90% of the pregnant women who, in past decades, contracted it. “We are in a terrible situation and going into a worse situation,” Angela Rasmussen, a Canadian virologist, recently warned. “I don’t know if the bird flu will become a pandemic, but if it does, we are screwed.”

So far, we have been extremely lucky. The dozens of farm workers who have fallen ill from avian flu this last year, most from exposure to infected dairy cows, appear to have contracted a mild version of the virus. Most have now recovered. Last month, however, the far deadlier D1.1 variant of the virus was discovered in a herd of cattle in Nevada. Should such a lethal variant mutate into a transmissable form, and become capable of binding to receptors in our lungs, the resulting pandemic could lead to societal chaos and mass mortality.

For too long, we have behaved as if our species were “an island entire of itself,” and we were the only beings whose lives mattered or had value.

Just before leaving office, then-President Joe Biden transferred $590 million to Moderna to accelerate development of a bird flu vaccine. Other companies are also working on vaccines. But it’s anyone’s guess if they will be ready in time. Even with a vaccine, Americans can expect little help from their government should a bird flu pandemic materialize, since President Donald Trump is eviscerating the federal agencies responsible for public health and disease prevention. The new administration has slashed the budgets and staff of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and FEMA, suppressed CDC updates on bird flu, and taken the U.S. out of the World Health Organization—the international agency responsible for monitoring and providing guidance on global public health threats, including pandemics.

Worsening matters, any federal response to an avian flu pandemic would be in the hands of Robert F. Kennedy Jr., the new secretary of Health and Human Services—a notorious vaccine skeptic. President Trump himself would likely respond to a new pandemic not by protecting the most vulnerable Americans, but by using the crisis to expand his own powers, if not to impose martial law.

Perhaps our luck will hold, and we will somehow all avoid getting avian flu. But we can’t count on it. Nor can we afford to go on ignoring the inextricable links between our oppression of nonhuman animals and growing pandemic risk.

The best way to prevent zoonotic pathogens from making us sick in future is to begin transitioning to an all plant-based diet. In doing so, we would not only spare billions of animals further suffering, but also mitigate a great deal of environmental damage to our planet. And we ourselves would be healthier for it. Scientists have shown that vegans have lower rates of heart disease, stroke, cancer, and type 2 diabetes than meat-eaters. One study in JAMA found that vegans may even live longer than “omnivores” who consume animal products.

Tragically, however, rather than rethink our dietary choices, we continue to cling to the animal system, and to its vast cruelties, against the better claims of reason and conscience. Few people indeed seem aware of the violence and suffering that attend even “ordinary” animal production. To produce eggs, for example, tens of millions of chickens are jammed into cages so small that they cannot extend even a single wing. The birds’ beaks are painfully cut off to keep them from pecking at their cell mates in distress. Then the chickens are repeatedly starved to shock their systems into producing more eggs. Finally, they are violently grabbed and thrown into a truck, and brought to the slaughterhouse. There, they are shackled upside down by their legs and have their throats cut, often while still conscious. Many are boiled alive in feather removal tanks. Billions of male baby chicks—of no use to industry—are meanwhile ground up alive or are simply tossed away in dumpsters, to suffocate or die from dehydration.

These and other barbaric practices have no place in society today. Even now, however, Americans are concerned only about soaring egg prices, not about the suffering of the tens of millions of animals being killed in ventilator shutdowns across the country. The idea that we should simply stop eating eggs—for the birds’ well-being as much as for our own safety—appears not to have occurred to anyone.

As an ethicist who has spent decades lecturing and publishing on animal rights, hoping to convince people that there is a better way to live a human life than by imprisoning and killing our fellow beings, I find it beyond discouraging how little progress has been made toward ending our violence against animals in the food economy. The avian flu threat, however, has now given us an opportunity to rethink our existential and ethical relations with the other animals of our planet, and to recognize how closely our fates are bound together.

“Ask not for whom the bell tolls—it tolls for thee.” When the poet John Donne wrote these words, centuries ago, it was customary for churches in England to toll their bells to announce the death of someone in the community. We are deeply connected to one another, Donne was saying, and what happens to one, happens to all.

“No man is an island entire of itself,” Donne wrote. Each of us “is a piece of the continent, a part of the main.” Every death therefore “diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind.”

Donne’s poem has taken on new significance, as avian influenza now closes in around us. Our species is not alone on the Earth, but part of the biotic main, a “piece of a continent” teeming with myriad other suffering, mortal beings. And what we do to the other animals, we do also to ourselves.

For too long, we have behaved as if our species were “an island entire of itself,” and we were the only beings whose lives mattered or had value. Now, after long treating our fellow creatures with violence and contempt, as mere “things” to be exploited and killed for our purposes, our karmic debt is coming due, in a ruined Earth and escalating pandemic risks. The tolling of the bell today is avian flu, and it tolls for us.

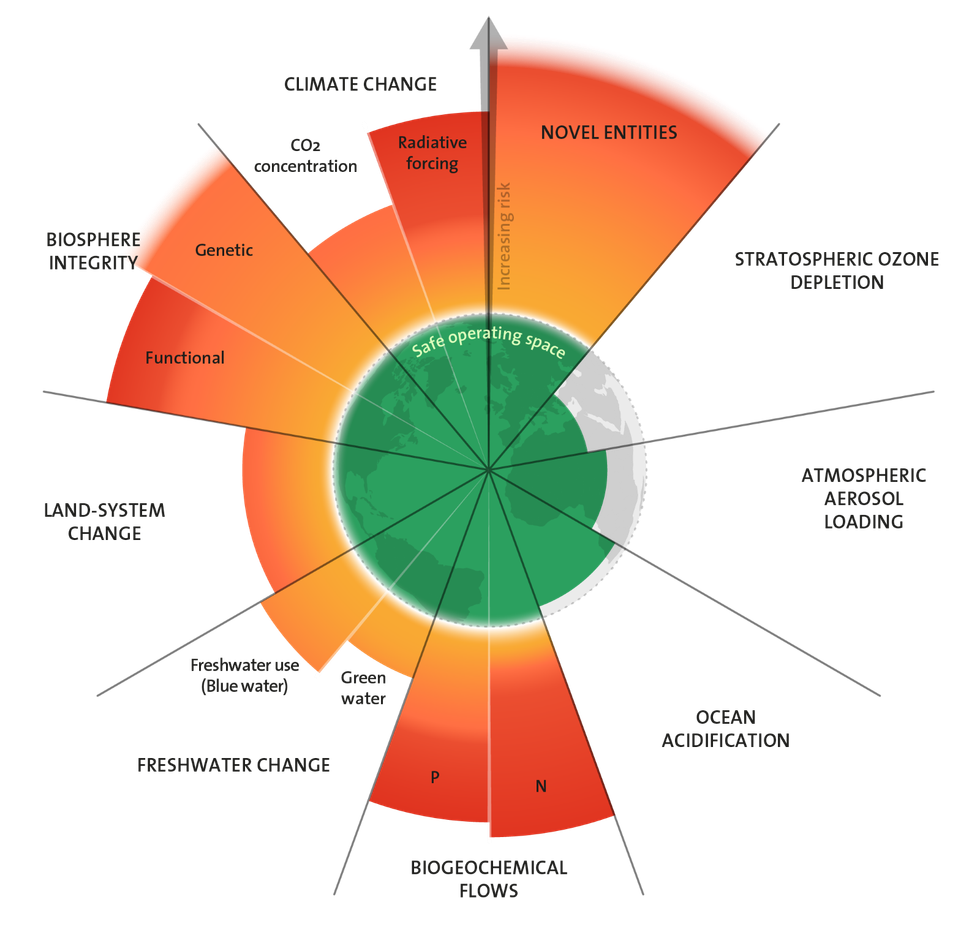

The 2023 update is shown to the Planetary boundaries. (Graphic: Azote for Stockholm Resilience Centre, based on analysis in Richardson et al 2023/ CC BY-NC-ND 3.0)

The 2023 update is shown to the Planetary boundaries. (Graphic: Azote for Stockholm Resilience Centre, based on analysis in Richardson et al 2023/ CC BY-NC-ND 3.0) Thousands of cattle mill about or huddle under shade structures at a large cattle ranch where they spend the last few months of their lives before going to slaughter in Coalinga, California, USA, 2022. (Photo: Vince Penn / We Animals)

Thousands of cattle mill about or huddle under shade structures at a large cattle ranch where they spend the last few months of their lives before going to slaughter in Coalinga, California, USA, 2022. (Photo: Vince Penn / We Animals) A horned Pineywoods bull watches a white and black spotted Kune Kune pig at a regenerative farm in North Carolina, USA. (Photo: Mike Hansen / Getty Images)

A horned Pineywoods bull watches a white and black spotted Kune Kune pig at a regenerative farm in North Carolina, USA. (Photo: Mike Hansen / Getty Images)