SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

Three decades of a consistent warming trend have made a greener Arctic the new normal, and "widespread, sustained changes" are set to come to region, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration said in an assessment this week.

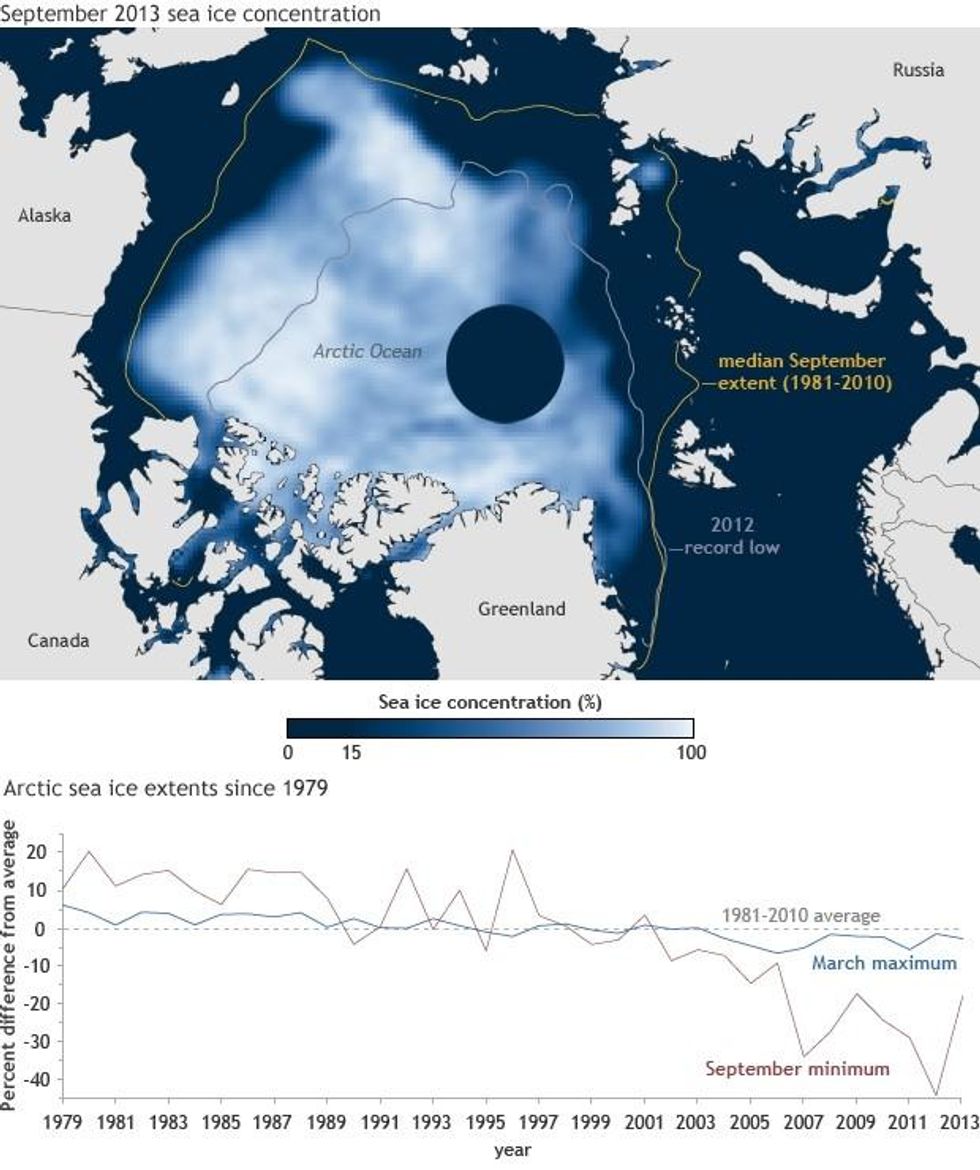

While its newest annual Arctic Report Card doesn't reveal the series of record-setting events seen in last year's analysis, the NOAA says the warming trend remains clear.

"The Arctic caught a bit of a break in 2013 from the recent string of record-breaking warmth and ice melt of the last decade," David M. Kennedy, NOAA's deputy under-secretary for operations, told press at the American Geophysical Union annual meeting in San Francisco. "But the relatively cool year in some parts of the Arctic does little to offset the long-term trend of the last 30 years: the Arctic is warming rapidly, becoming greener and experiencing a variety of changes, affecting people, the physical environment, and marine and land ecosystems."

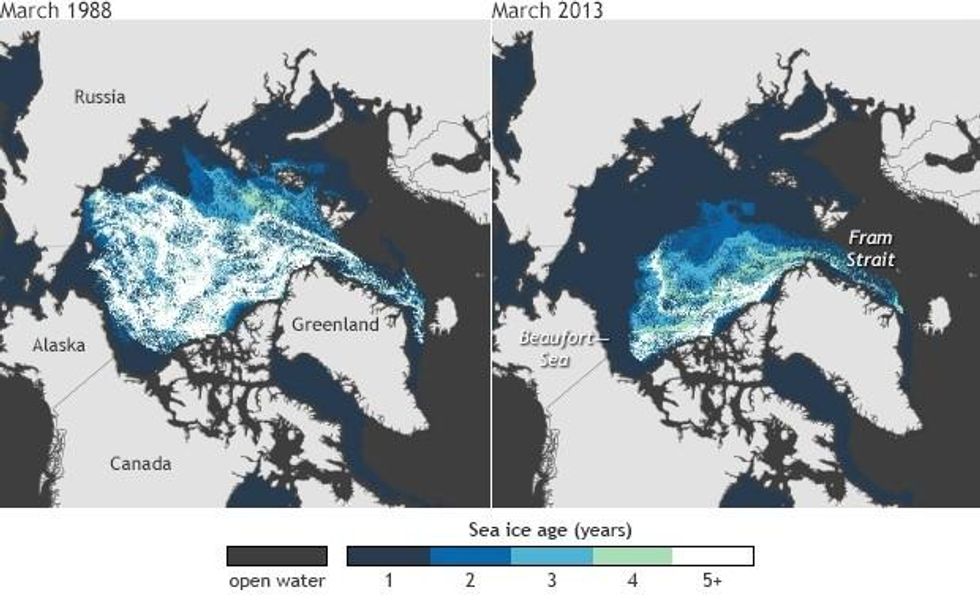

The yearly assessment, based on contributions from over 147 authors, shows that the Arctic had its sixth warmest year on record; the Arctic sea ice extent was the sixth smallest on record, and the seven lowest recorded sea ice extents happened in the last seven years. Further, the thickness of the ice continues to decrease. The decreased ice coverage has brought warmer than average temperatures to Arctic boundary waters in the summer of 2013. The North American snow cover was the fourth lowest on record, while the snow cover in May over Eurasia hit a record low.

Some caribou and reindeer populations hit unusually low numbers, while climate change appears to be pushing some fish from warming waters into the Arctic.

"The Arctic Report Card presents strong evidence of widespread, sustained changes that are driving the Arctic environmental system into a new state and we can expect to see continued widespread and sustained change in the Arctic," said Martin Jeffries, principal editor of the 2013 Report Card, science adviser for the U.S. Arctic Research Commission, and research professor at the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

* * *

The NOAA provided this video to accompany the report card:

Arctic Report Card 2013Arctic Report Card: Update for 2013 - Tracking recent environmental changes, with 18 essays on different aspects of the ...

For Russia, which recently seized a Greenpeace ship and is prosecuting 30 of the group's activists for attempting to scale an oil platform, the temptation to exploit the Arctic Ocean is especially powerful. Russia's economy is heavily dependent on exports of oil and gas, and the government relies on these sales for much of its income. Until recently, the Russians could draw on reservoirs in western Siberia to satisfy their needs, but now, with many of these fields in decline, they are counting on Arctic supplies to maintain current production levels. "Our first and main task is to turn the Arctic into Russia's resource base of the 21st century," Dmitri A. Medvedev, then the president, declared in 2008.

The Russians have explored drilling options in several offshore areas of the Arctic. In the Pechora Sea, above northwestern Siberia, the Russian energy giant Gazprom has installed its Prirazlomnaya platform -- the one protesting Greenpeace activists attempted to board. Further east, in the Kara Sea, the state-owned Rosneft is collaborating with ExxonMobil to develop promising deposits; Rosneft has also teamed up with Statoil of Norway and Eni of Italy to investigate prospects in the Barents Sea.

But Russia is hardly alone in seeking to exploit the Arctic. Norway, like Russia, derives considerable income from gas and oil exports and is under pressure to develop reserves in the Barents Sea to compensate for the decline of its existing fields in the North and Norwegian Seas. Other areas of the Arctic are also being eyed for development. Cairn Energy of Edinburgh has sunk exploratory wells in waters off Greenland, for example, while Royal Dutch Shell is attempting to develop fields off Alaska.

For all of its promise, however, the Arctic is not likely to surrender its resources easily. Sea ice covers much of the area in winter, and storms pose a constant danger. Global warming is likely to reduce the extent of sea ice in the summer and fall, permitting extended drilling operations, but it could also produce unruly weather and other perils. Adding another layer of risk, many of the boundary lines in the Arctic remain to be fully demarcated, and various Arctic powers have threatened to use military force in the event that one or another intrudes on what they view as their sovereign territory.

The severe challenges of operating in the Arctic have already proved daunting for Shell, which has spent $4.5 billion to exploit reserves off Alaska but has yet to drill a single producing well. Some of these challenges are legal -- indigenous communities and environmentalists, fearing the contamination of local waters and a threat to wildlife, have filed lawsuits to prevent the company from drilling.

In addition, the Arctic itself has proved to be a formidable adversary: In the summer of 2012, during Royal Dutch Shell's first attempt to probe its Arctic deposits, shifting winds and floating ice halted drilling. Several months later, when one of its drilling rigs ran aground during an especially severe storm, Shell announced that it would suspend operations in Alaska's Arctic waters and that before it proceeded, it would bolster its capacity to operate there.

Shell's misfortunes have heightened concern that Arctic drilling poses an unacceptable threat to the region. Any major spill that occurs there is likely to prove far more destructive than the one produced in the Gulf of Mexico by the Deepwater Horizon disaster in April 2010, because of both the lack of adequate response capabilities and the likelihood that ice floes and sea ice will impede cleanup operations. As more companies push into the Arctic and accelerate their operations there, the risk of accidents and spills is bound to increase. The fact that Shell -- one of the most technically advanced oil companies -- has so far proved unable to overcome these risks should provoke intense concern over the prospect that other, less proficient firms will soon be operating in these perilous waters.

The risk of conflict over the ownership of contested territories is likely to grow. Five of the Arctic states have asserted exclusive drilling rights to boundary areas also claimed by one of the others, and control over the polar region itself remains contentious. In an area with the "potential for tapping what may be as much as a quarter of the planet's undiscovered oil and gas," Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel warned recently, "a flood of interest in energy exploration has the potential to heighten tensions over other issues."

So far, not one of these disputes has provoked a military response, and the Arctic states have pledged to refrain from such action. However, most of the Arctic states have also asserted their right to defend their offshore territories with force and have taken steps to enhance their ability to fight in these areas. Russia, for example, recently announced plans to establish what it calls a "cutting-edge military infrastructure" in the Arctic.

None of this, however, is likely to deter other interested countries. With the demand for oil at an all-time high and existing fields incapable of satisfying global needs, the major energy firms are bound to pursue every conceivable source of supply. It is essential, then, that tough constraints be placed on Arctic drilling operations and that steps be taken to reduce tensions in the area. Some progress has been made by the Arctic Council, a consultative forum of Arctic nations. But much remains unresolved.

One way to impose formal restraints would be to devise and adopt an Arctic Treaty modeled on the Antarctic Treaty of 1959. Like that earlier measure, an Arctic compact would delineate the region's maritime boundaries and establish limits on military activities. It could also impose environmental protections and provide for the safe passage of civilian vessels through Arctic waters. In the end, no extra measure of oil and natural gas is worth the destruction of pristine wilderness or the onset of an Arctic arms race.