SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

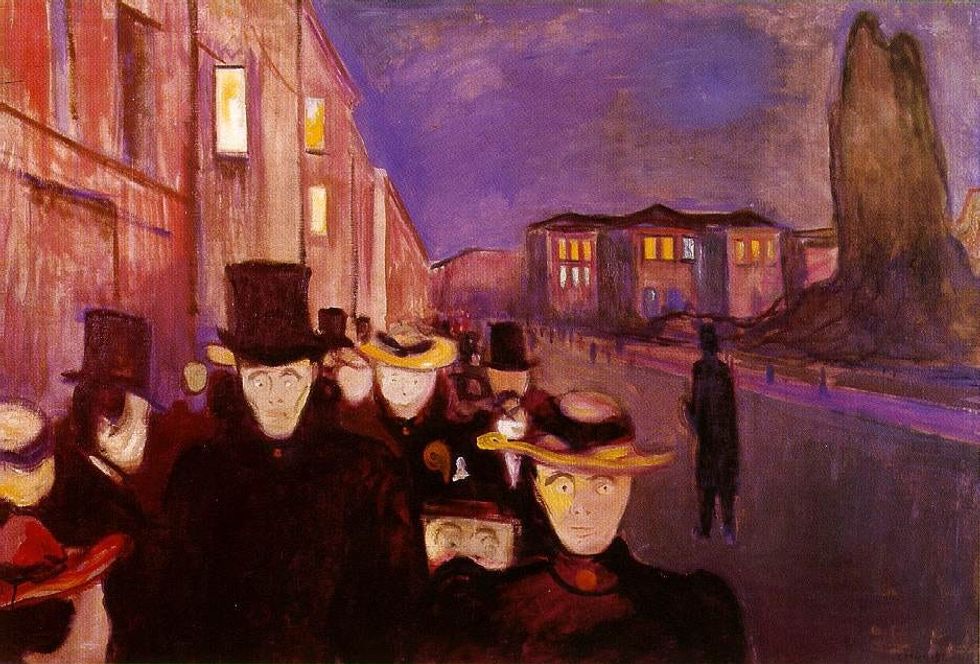

Do not pretend to be anything other than yourself attempting to gain the approval of heartless authority and petty tyrants of the everyday kind.

"I need to be alone. I need to ponder my shame and my despair in seclusion; I need the sunshine and the paving stones of the streets without companions, without conversation, face to face with myself, with only the music of my heart for company."—Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer

Deep down, we struggle to come upon accurate words to describe the terrible beauty of our aloneness. In this plight, we are together. In this musing, I, listening to the music of my heart, will attempt to hobble through and send back dispatches conveying a lexicon of aloneness.

A lesson I hope to learn by scribing a travelog of the dark: I've noticed, people who have survived the howling abyss of abandonment, and have been freed from its grip of grief, have been transfigured by the ordeal. Rarely, as a consequence, do such individuals act as errand boys, muscle, or apologists of oppressors.

They have snatched this from the mouth of despair, it would be tragic to be false to the forces that formed them. Thus make a vow to self: Do not pretend to be anything other than yourself attempting to gain the approval of heartless authority and petty tyrants of the everyday kind. Your wounds demand you speak your truth.

Even in our cultural atomization, we are connected to those cast out; we are bonded to society's denizens of the dark, to those who feel the pain of the suffering Earth; to those who the misnomer known as normalcy casts from conscious awareness; to those who capitalist functionality (i.e., crackpot realism) brutalizes, kicks to the curb, and condemns to madness and death… yet life on life's terms, confronts us with innumerable, seemingly infinite connections. Within, we mirror all things. We, unbeknownst to ourselves, communicate with all things. Not only the realm of the human but soil, ocean, storm, star, galaxy, electron…

We, moment to moment, travel the bridge between each other's heartbeats. We are connected both with what we love and what we shun. Moreover, what we cast out and shun will return as affliction. Hence, the Earth herself is unwell and she rages in floods and firestorms.

Breathe in deep, clear your throat, and make exhortations on behalf of the voiceless. If you have a gift for music, compose and play them a song, let the weary take refuge in the rest between musical notes. Display sacred vehemence toward life-defying oppressors who contrive to make the life of the many a prison by incarceration of the heart.

When the culture of a nation, intoxicated on extraverted mania inherent to Mephistophelian capitalism, disallows the visions of its denizens of despair into the conversation, compensatory angels borne from the unconscious (what people in times past knew as the soul) will descend bringing on a cultural darkness. In the sterile, clinical language of our time, the phenomenon is termed a pandemic of depression.

Emissaries, invisible in daylight glare, appear in the dreams of the scorned and forsaken; the visitors whisper verse to those capable of stillness, and guide the willing into moments of inadvertent reprieve. In short, deliverance occurs by means of easing the burden of self—which is a gentle way of saying, aiding one in getting the living hell over oneself. These emissaries impart the message the visible world can be a mirage. Hope is an invisible force allied with luminous angels whose light would blind us upon sight. Hence, we are moved to transformation by a force not perceptible during quotidian day.

Paradoxically, because all things arrive freighted with their opposite (enantiodromia) bearers of hope are, often, those aforementioned lonely, despair-wracked individuals driven to stand at the edge of the abyss—the abjectly lonely who have been moved, by desperation, to implore the unseen for mercy.

No person wants to arrive at such a place. One would choose, and most do, a mundane life wherein we follow the signposts, on an exclusive basis, of the visible world—yet is, in essence, given our human proclivity for habitual self-reference, a graceless tour of a house of mirrors. Oh—the hellish mix of confusion and blandness of the choice.

Prayer before sleep: Lord of nightmares bestow grace on me by allowing me to be reborn from within the womb of night. Despair's blackness grants the intrepid traveller the ability to navigate darkness, thereby avoiding a life defined by the limbo of complacency.

A person open to being ministered to, thus transformed, by a numinous voice, calling from the darkness at the edge of the daylight world, will, in all likelihood, spend their days alone, all too often suffering the pain of wounds inflicted by rejection. Loneliness will be a constant companion.

But as Rilke avers in verse:

You, darkness, that I come from

I love you more than all the fires

that fence in the world,

for the fire makes a circle of light for everyone

and then no one outside learns of you.

But the darkness pulls in everything—

shapes and fires, animals and myself,

how easily it gathers them!—

powers and people—

and it is possible a great presence is moving near me.

I have faith in nights.—Rainer Maria Rilke, "You Darkness"

Often, a shunned soul, one who travelled through the world of mindless consensus' inferno of fuckwit and has returned, will be put on the defensive by normalcy's bullies and challenged to make an accounting of himself—i.e., to account for the unaccountable. In the end, one who has seen and survived one's own darkness, will be able to apprehend the darkness within his inquisitors. At the speed of a synapse, his tormentors will go from bullying to claiming victimization.

For, when backed against the wall, he is often moved to speak in a soul-plangent lexicon that causes a collapse, even for an instant, of his tormentor's protective yet ad hoc walls of coping—thus revealing the fragile banality that governs their lives. In so doing, he has committed an act, in nice society, that will never be forgiven.

Rilke surveys the scene and sends back this dispatch in verse:

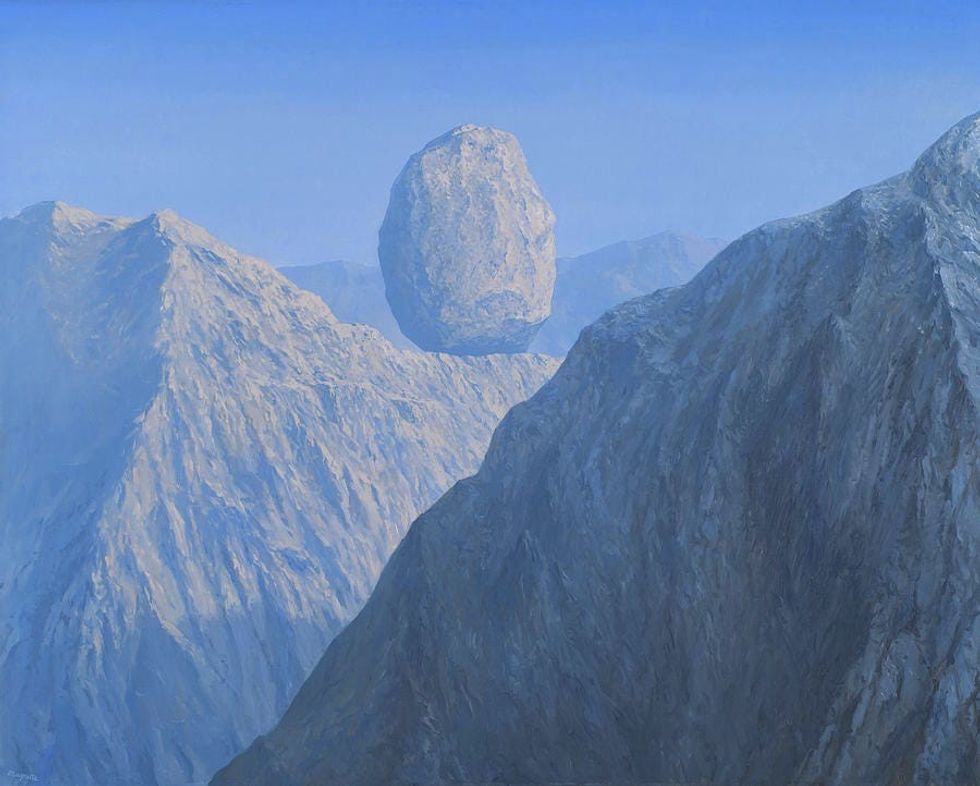

Exposed on the cliffs of the heart. Look, how tiny down there,

look: the last village of words and, higher,

(but how tiny) still one last

farmhouse of feeling. Can you see it?

Exposed on the cliffs of the heart. Stoneground

under your hands. Even here, though,

something can bloom; on a silent cliff-edge

an unknowing plant blooms, singing, into the air.

But the one who knows? Ah, he began to know

and is quiet now, exposed on the cliffs of the heart.

While, with their full awareness,

many sure-footed mountain animals pass

or linger. And the great sheltered birds flies, slowly

circling, around the peak's pure denial.—But

without a shelter, here on the cliffs of the heart.—Rilke, "Exposed On The Mountains Of My Heart"

Stop for a moment and take it all in. This life… on our Earth. The beauty. The terror. Notice: The terror involved in taking in the beauty of it all. The act will awaken your heart. Ask yourself: Am I on my heart's path? Or does this road lead me, again and again, into the dominion of exploiters? If you received an affirmative in regard to the latter question, I suggest, after you cease weeping—a sane response to you taking notice of the heart-devoid landscape where you have strayed—ask yourself: How can I reorient myself as to the direction of my heart's path?

Do you feel thwarted by circumstance, by the inherent miseries in facing capitalist hierarchies of immovable power and the system's architecture of exploitation? Rebel by engagement with the eternity delivery system of the imagination. Doing so does not translate into idle fantasy. By a receptivity to originality, by being moved to enthusiasm by acts of creativity… will provide the libido to trundle through the living landscape of imagination; thereby, one does not need to be an artist to live and engage the world in an artful manner.

Become a one person hallelujah chorus for originality. Within you, glide wheels of fire. The valley of bones rises as an army of flesh. This is your exodus out of bondage.

Are entertainments like these seriously acknowledging the deep-seated anxieties—and anger—that Americans are feeling today? Or is the entertainment industry just shamelessly exploiting those anxieties and that anger?

America’s richest have never been richer. Our over 800 billionaires ended 2024 worth a combined $6.72 trillion. Today, almost two months later, Americans make up 14 of the 15 richest people in the world. Just these 14 alone hold a combined net wealth of over $2.5 trillion.

One predictable consequence of numbers like these: Our world’s “super yacht” sector is doing spectacularly well, as the annual Miami International Boat Show this month convincingly confirmed. The star of this year’s show turned out to be a super yacht nearly the length of a football field.

Drivers on America’s highways and byways, meanwhile, are now needing to make room for the newly released latest luxury super car from Rolls-Royce. The new Black Badge Spectre can “sprint from zero to 60 mph in just 4.1 seconds.” The base price: a mere $490,000.

We need more, let’s all agree, than shows and movies that skewer the rich.

Amid all this excess, the fortunes—and power—of America’s most fortunate just keep mounting ever higher. At the expense of the rest of us. The world’s wealthiest billionaire, Elon Musk, has found an particularly lucrative new hobby: axing the jobs of federal employees working at agencies that protect the health and economic security of average Americans.

Researchers and analysts worldwide are, for their part, continuing to carefully track the ongoing—and historic—concentration of America’s wealth. But Hollywood, these days, may actually be tracking this concentration even closer.

The wealth, privileges, and formidable clout of our richest, Hollywood understands, are outraging average Americans. We’ve become a nation hungry for entertainment that expresses that outrage, and Hollywood has been all too happy to offer up that entertaining.

“The popularity of ‘eat the rich’ media—like Saltburn, White Lotus, Parasite, Triangle of Sadness, The Menu, Infinity Pool, The Fall of the House of Usher, and the Knives Out movies—has reached a fever pitch,” as the culture critic Kelsey Eisen puts it.

This “vilification of the rich,” adds Eisen, regularly includes “rich characters undergoing some terrible event—ranging from marital troubles to shipwrecks to even death—as some sort of comeuppance for being wealthy.”

“We do love watching the 1% get their comeuppance, don’t we?” agrees Adrian Lobb, another widely published and perceptive writer on contemporary culture.

Lobb last year interviewed Jason Isaacs, one of the stars of The White Lotus, an Emmy Award-winning comedy drama created for HBO. Isaacs told Lobb that he also “absolutely” loves the joy of the “comeuppance” moments swirling all around us.

“We watch these people who look like they’ve got everything,” Isaacs explains, “and console ourselves with the fact that they’re miserable as hell.”

The White Lotus features “sun, sea, sex” and super-rich secrets, notes the culture analyst Lobb, “with a side order of slaying.” Each season of the series showcases a set of gastronomically obsessed wealthy out to enjoy life at an exotic luxury resort, with no guest, quips writer and filmmaker Alyssa De Leo, “safe from being skewered—figuratively and literally.”

Another skewering of the “successful” takes place, De Leo observes, in the widely acclaimed film Triangle of Sadness, the story of an ultra-wealthy cruise ship that sinks and leaves the survivors “stranded on a desert island” with “the upper-class guests lacking any resources or knowledge of how to survive.”

Still another popular entry in the “comeuppance” genre, the thriller You’re Next, has a wealthy family celebrating an anniversary in a country mansion that masked assailants suddenly besiege. The assailants turn out to be hired guns that some members of the family had retained to ensure and hasten the inheritances they saw as their due.

And atop the genre’s most-watched list sits Squid Game, “one of Netflix’s most important and impactful television shows ever.” This “too-close-for-comfort dystopian thriller,” the Observer’s Brandon Katz celebrates, “cleverly spins socioeconomic inequality into thriller life-or-death games.”

Are entertainments like these seriously acknowledging the deep-seated anxieties—and anger—that Americans are feeling today? Or is the entertainment industry just shamelessly exploiting those anxieties and that anger? Are “eat the rich” films and series, as the arts critic Kelsey Eisen muses, “moving the political conversation forward” or merely “providing soothing, satisfying, and self-congratulatory entertainment”?

Eisen herself sees the answer to that question through the latter prism. She considers “eat the rich” entertainment as “less of a political statement and more of a soothing concession,” as “basically class-anxiety pornography, pure catharsis without a real message or call to action.”

Even so, Eisen readily confesses that she does indeed enjoy watching many of today’s “eat the rich” shows and movies and does see real value “in using art to encapsulate popular sentiments and anxieties and to normalize progressive sentiments.”

So should you dare enjoy “class anxiety-soothing media”? Sure, Eisen concludes. Just be sure that this media “doesn’t soothe you into being too complacent to ever actually do anything” to end that class anxiety.

Amen. We need more, let’s all agree, than shows and movies that skewer the rich. We need, now more than ever, a political movement powerful enough to break the billionaire lockgrip on our future.

Works like Promemoria—Reminder (Sending Out an SOS) by EMA can get to the heart of the matter by tapping not just the intellect but the emotions, putting us in touch with a deeper sense of meaning too often ignored in our rush to deal with the crises of the moment.

The world is in danger, mind-numbingly so, from a combination of crises: disease, hunger, mass displacement, racial and economic inequality, war and the threat of more war, a rampaging climate crisis, and an accelerating nuclear arms race (and that’s just for starters)—all occurring in a climate of massive mis- and disinformation that makes it ever harder to build a consensus toward solutions to the multiple problems we face.

Words can’t fully express our current predicament. We need other tools and other ways of making sense of the situation we now find ourselves in.

This should be a time for action and activism on behalf of our species and our planet. While there’s certainly a fair amount of that already, the combined weight of the risks we face makes all too many of us turn inward toward family and friends, or outward to find scapegoats for our problems. And yes, there are still moments of joy, optimism, and constructive action. Unfortunately, they are increasingly hard to sustain amid relentless daily attacks on people’s lives, livelihoods, and basic dignity.

One of the best ways to find a place of balance and light amid all the chaos is by creating and appreciating art, which can get to the heart of the matter by tapping not just the intellect but the emotions, putting us in touch with a deeper sense of meaning too often ignored in our rush to deal with the crises of the moment.

It’s in this context that I read and viewed Promemoria—Reminder (Sending Out an SOS) by EMA (Enrico Muratore Aprosio), a Geneva-based human rights advocate, humanitarian, and artist. The words in the book, which addresses Covid-19, the climate, and the prospects of nuclear war through poetry, prose, and storytelling, are compelling. But the artworks that punctuate the text are truly stunning, using bright colors and complex designs that incorporate pictures of both historical and imaginary figures—its images ranging from Karl Marx to Marilyn Monroe, Ronald Reagan to the Mona Lisa (wearing a Covid-19 protective mask).

The book honors the spirit of altruism and courage, most notably in a section dedicated to Mbaye Diagne, a Senegalese peacekeeper who saved up to 1,000 lives amid the 1994 genocide in Rwanda, only to be killed in a mortar attack 12 days before he was set to return home.

Melissa Parke, director general of the Nobel Prize-winning International Coalition to Abolish Nuclear Weapons, captures the sense of the book well, suggesting that Aprosio’s “use of beautiful animals, striking colors, and magical happenings communicates both the urgency of the situation we face and reminds us of what we stand to lose if we don’t change course.”

Not only will the book have its own impact, but it will hopefully inspire others to produce projects that address our most urgent problems in new ways, moving people to take action grounded in our common humanity.

Appreciating what we still stand to lose couldn’t be more crucial in the world we now face. Savoring everything from the signal achievements of humanity (writ large) to the pleasures and accomplishments of our everyday lives matters deeply, both as a motivation to continue working for change in an ever-messier world and as fuel for sustaining us in a struggle of unknown duration.

Yes, EMA’s book is grimly grounded in reality, even as it (literally) paints a picture of a world that could be so much better. One of my favorite panels in the book is entitled “Every Day More Bullshit,” just because, well, it seems all too sadly appropriate to the moment we’re in.

There’s also a chapter called “Radioactive Beasts,” inspired by George Orwell’s dystopian novel Animal Farm. The animals Aprosio writes about are worried by the state of the world and concerned that humans aren’t taking the risks posed by current conflicts seriously enough.

In April 2023, some of Aprosio’s fictional beasts were projected onto buildings in New York City’s Times Square with support from the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN). Other portions of the book could be displayed across this embattled planet of ours in a similar fashion to good effect.

There’s more to EMA’s book than can be taken in at a sitting, or even many sittings, or certainly summarized in an essay like this. Still, get your hands on it if you can. It can serve as an inspirational reference work you can dip into at any time to reenergize yourself or contemplate what a different world might indeed look like. In that way, it reminds me of the effects of Afrofuturist art and literature, not because the forms necessarily resemble each other, but because both approaches underscore the desperate need for a bold vision of what a new world might look like—a vision of what anyone trying to change things might dream of.

Promemoria is anything but the only current art project that takes on nuclear weapons and related dangers. One of the most interesting current networks is Artists Against the Bomb, a global organization of creators who have produced an amazing array of antinuclear posters, among other works.

Another vital project in a world where nuclear weapons are proliferating and the U.S. is planning to invest up to $2 trillion dollars in the (yes, this is indeed the term!) “modernization” of its nuclear force in the coming decades is Bombshelltoe. It’s a policy and arts collective that defines itself as “a creative organization pushing for an active exploration of arts, culture, and history to promote nuclear nonproliferation, arms control, and disarmament for the next generation.” One of its prominent efforts is the Atomic Terrain Project, which highlights how nuclear weapons have “seeped into our waters and tapped into our soil” and “continue to harm all life, human and non-human alike.”

I was fortunate enough to see an exhibition that the project mounted at the 2024 New York Art Book Fair entitled “How to Make a Bomb”—a book with the same title was also released then—organized and presented by Gabriella Hirst, Warren Harper, Tammy Nguyen, and Lovely Umayam (the founder of Bombshelltoe). The exhibit was built around a flower, the Rosa Floribunda, or—yes!—“Atom Bomb,” which Hirst describes as “a garden rose that was cultivated and named in 1953 during the Cold War arms race to commemorate Britain’s newfound status as a nuclear power.” Hirst has taken the lead in cultivating (and you might say pacifying) that rose, while getting it planted in gardens throughout the United Kingdom and beyond as an antinuclear gesture of beauty.

At the book fair, attendees could learn how to plant and maintain just such a rose while engaging in conversations about the history and devastating impact of nuclear weapons or checking out basic documents and books about the nuclear age. Such an indirect (even flowery!) route into truly grim subject matter drew interest from people who might not normally pick up a book on, or read an article about, the dangers of nuclear weapons but were fascinated by the physical process of grafting a rose and then willing to stay for open-ended conversations about the growing nuclear dangers in our world.

When asked why the project chose to use a rose as an entry point into discussions of such ominous and grim subject matter, Lovely Umayam noted that “nuclear issues alone can feel abstract and alarmist” and eerily unapproachable. As Gabriella Hirst put it, the project “is about taking the sublime into your own hands and working through that in small ways… to reduce fear among non-experts.”

At the same book fair where I encountered the Rose Project, I had the pleasure of meeting Ben Rejali, an organizer of the art and political website Khabar Keslan. Recent essays there include an interview with Palestinian filmmaker Khaled Jarrar, but I was first drawn to the project’s printed works, including reproductions of stamps from Iran and South Asia going back to the 1950s. There were, of course, numerous stamps portraying the once-dreaded Shah of Iran. There was also one of the CIA’s logo with blood running down it, a reference to the agency’s role in the 1953 coup that installed the Shah as Iran’s autocratic ruler. Perhaps the most emotionally powerful product of Khabar Keslan, however, may have been a collection of poems entitled “Salute to Olives” by the late Omar al-Bargouthi, many of which were written while he was being held in Israeli prisons.

On a planet where nuclear dangers are only growing, both Promemoria and the Atomic Terrain project underscore the importance of finding new ways to communicate about this increasingly fragile and endangered planet of ours that inspire creativity and action rather than fear, paralysis, and denial. At a time when challenges to fundamental rights are hurtling toward us at warp speed, taking the time to experience artworks of any kind can seem like a distinct luxury, but don’t believe that for a second. Such art is a key to reclaiming our humanity and getting in touch with the creative, collaborative impulses that could help save our planet. A pause, artistic in nature, to reflect and recharge our psychic batteries can go a long way toward helping us to cope with this all too strange present moment and build for the future. Promemoria provides us with that precious opportunity.

Music, theater, painting, and other forms of artistic expression have, in fact, been part of every major movement for change in recent memory. The Federal Theatre Project of the 1930s, funded as part of the Works Progress Administration of President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the era of the Great Depression, hired unemployed performers and writers who produced more than 800 plays and dance events. In the process, they highlighted work by under-represented groups, including African Americans via the Negro Theatre Project and the African-American Dance Unit. It also funded foreign language plays in Spanish, Yiddish, and German until Congressman Martin Dies, Jr., head of the House Un-American Activities Committee, led a successful charge to defund the program because of its advocacy of racial equality and other progressive themes.

Theater, however, continued to play a central role in progressive movements of the 1960s and 1970s, from Teatro Campesino, born during the United Farm Workers Union’s organizing drives in California; to the Bread and Puppet Theater, a staple of anti-war efforts; and the San Francisco Mime Troupe, whose plays captured a whole range of progressive themes, often in hilarious fashion. And don’t forget the freedom songs that were at the core of the civil rights movement, sung by demonstrators at mass rallies and activists detained in local jails in the South.

The anti-nuclear movement of the 1980s was also sustained and amplified by works of art. Its best-known cultural product was undoubtedly the TV movie The Day After, a fictionalized treatment of the impacts of a nuclear war viewed by more than 100 million people when it aired on ABC in November 1983. But there was also a steady drumbeat of anti-nuclear cartoons, some of which were assembled in a widely distributed collection entitled Warheads. Joel Andreas’s 77-page graphic comic book, Addicted to War: Why America Can’t Kick Militarism, proved to be a primer on the roots of the American war system from the 19th-century vision of “manifest destiny” to (in an updated edition) the Global War on Terror, taking on war profiteers and the role of the media along the way.

More recently, groups like the Yes Men and Reverend Billy and the Stop Shopping Choir have lampooned corporations and their executives through street theater and by posing as participants in corporate gatherings (and so underscoring the absurdity of their activities and world views). The Yes Men describe their work as using “humor and trickery to highlight the corporate takeover of society, the neoliberal delusion that allows it, [and] the corporate Democrats’ responsibility for our current situation.” Reverend Billy and the Stop Shopping Choir ridicule materialism in all its forms from Starbucks displacing local coffee shops to the excesses of the Disney Store in New York’s Times Square.

Paul Miller, aka DJ Spooky, has similarly engaged in a wide range of politically focused art projects, ranging from a Peace Symphony performed in Hiroshima to The Book of Ice, which addresses climate change, to a wide array of films, articles, and concerts. Robin Bell Visuals has produced films and art installations, including projecting the words “Pay Bribes Here” on the side of the Trump International Hotel in Washington. And there have been scores of anti-war anthems produced in virtually every genre of modern music from folk to jazz to rock to hip hop to heavy metal.

My colleague Khody Akhavi makes short compelling videos on topics ranging from the dangerous rise of AI-driven weaponry to the impact of the funding of think tanks by weapons contractors, the Pentagon, and foreign governments. And the Center for Artistic Activism partners with advocacy groups on specific projects, schools them in artistic techniques, and helps them build art into their campaigns and public education efforts. Their slogan: “we make social and environmental change more effective—and more creative.”

Better yet, the artists and projects cited above are just a sampling of the many forms of political art that have attracted audiences and encouraged activism at the local, national, and global levels. Promemoria is a worthy addition to this tradition. Not only will the book have its own impact, but it will hopefully inspire others to produce projects that address our most urgent problems in new ways, moving people to take action grounded in our common humanity. Given the world we’re now in, it can’t happen soon enough.