“My House Is a Rubbish Heap”

Gates rejects the view that climate change “will decimate civilization,” insisting instead that it “will not lead to humanity’s demise.” Of course, no one in the scientific community had argued that climate change would actually wipe out humankind, so he is indeed (and all too conveniently) attacking a straw man.

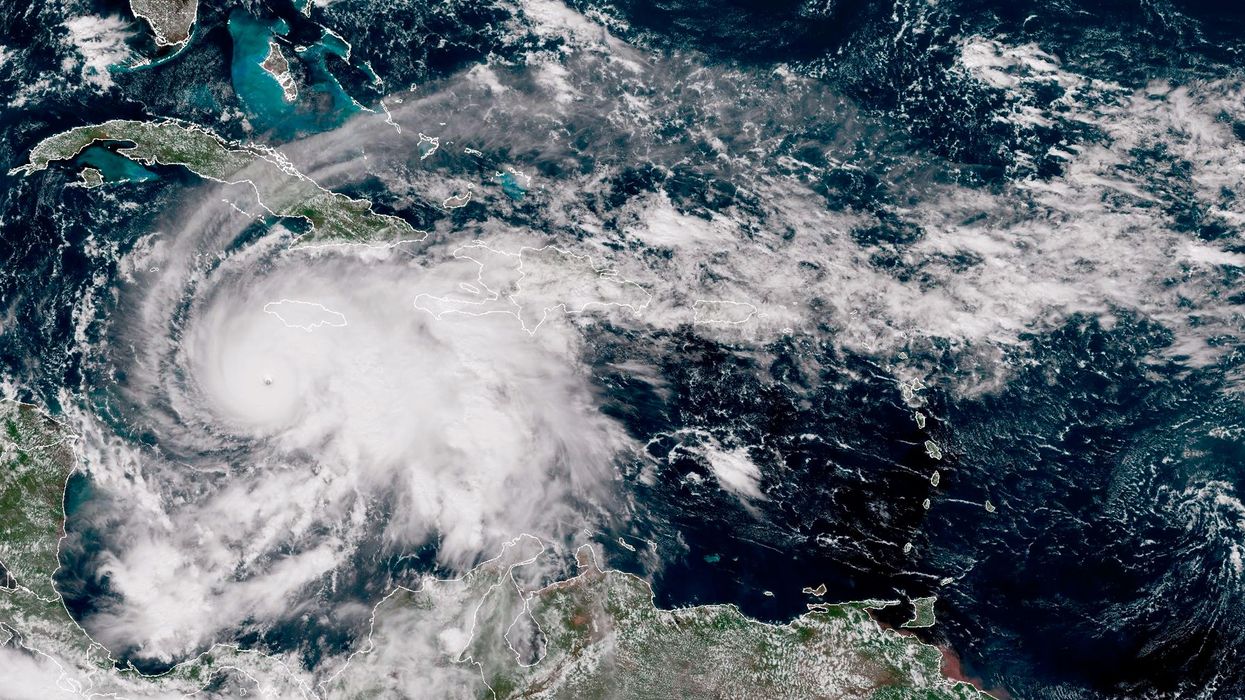

That he resorted to a description of such fallacious relevance shows how intent he is on engaging in a bad-faith argument. And that, in turn, raises the question of his motivation. After all, the possible decimation of civilization, as did indeed occur in parts of Jamaica recently, is quite different from the full-scale extinction of the human species, and it certainly raises questions of equity. The nearly half a million Jamaicans who will be without electricity for weeks and who may face severe food shortages because of crop damage will, of course, not be enjoying much in the way of “civilization” In the wake of Melissa. As Sherlette Wheelan of that island’s Westmoreland Parish said, “My house is like a rubbish heap, completely gone. If it wasn’t for the shelter manager, I don’t know what I would’ve done. She found space for me and others, even though her own roof was gone.”

And imagine this: the hurricanes of the future world we’re now creating by burning such quantities of fossil fuels, in which temperatures could rise by a disastrous 3 degrees Celsius, are likely to be so gargantuan as to make our present behemoths look sickly. Melissa was already a third more powerful than it would have been without climate breakdown. Heat up the Caribbean Sea even more, and the power of storm winds won’t increase on a gentle slope but exponentially. Scientists are already suggesting that we need a new Category 6 classification for such hurricanes, since our present 5 categories are inadequate, given their increasing power. Remember, at present, with Melissas already appearing, we have only experienced a global 1.3 degrees Celsius increase in temperature over the preindustrial norm. At issue is the quality of life and the degree of civilization that will be possible in a world where the temperature increase could be at least double that.

The Demand for Data Centers Cannot Be Met Sustainably

A decade ago, many of the companies in Silicon Valley seemed willing to take on the role of climate champions. Microsoft, where Gates made his career, pledged to be carbon negative by 2030. Jeff Bezos’s Amazon has already put more than 30,000 electric vehicles on the road and has pledged to reach net-zero carbon emissions by 2040. In general, you would think that Silicon Valley would be pro-science and hence willing to combat the use of fossil fuels and so the worsening of climate change. After all, the industry depends on basic scientific research, much of it produced by government-funded scientists.

As it turns out, though, the high-tech sector that has produced so many billionaires is instead simply pro-billionaire. This year, we were treated to the spectacle of future trillionaire Elon Musk, while still working with Donald Trump, firing 10% to 15% of all government scientists under the rubric of “the Department of Government Efficiency,” an act that, in the long run, could also help destroy American scientific and technological superiority. Climate scientists were especially targeted. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Agency is now so understaffed that the carnage of Hurricane Melissa had to be monitored by volunteers.

As it turns out, though, the high-tech sector that has produced so many billionaires is instead simply pro-billionaire. This year, we were treated to the spectacle of future trillionaire Elon Musk, while still working with Donald Trump, firing 10% to 15% of all government scientists under the rubric of “the Department of Government Efficiency,” an act that, in the long run, could also help destroy American scientific and technological superiority. Climate scientists were especially targeted. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Agency is now so understaffed that the carnage of Hurricane Melissa had to be monitored by volunteers.

The high-tech world’s abrupt turn to a rabid anti-science stance is likely the result of the emergence of large language models (also known as “artificial intelligence” or AI) and a consequent new romance with the burning of fossil fuels. This development made Nvidia, which produces the graphics-processing units that run much of AI, the first $5 trillion company. That AI has not yet proven able to increase productivity or produce any measurable added value has not stopped the hype around it from driving the biggest securities bubble since the late 1990s.

The AI phenomenon may functionally print money for tech billionaires, at least for the time being, but it comes with a gargantuan environmental cost. Its data centers are water and energy hogs and are poised to use ever more fossil fuels and so increase global carbon emissions significantly. MIT researchers estimate that “by 2026, the electricity consumption of data centers is expected to approach 1,050 terawatt-hours,” rivaling that of the energy consumption of whole countries like Japan or Russia. By 2030, it’s estimated that at least a tenth of electricity demand is likely to be driven by new data centers. MIT’s Noman Bashir concludes ominously, “The demand for new data centers cannot be met in a sustainable way. The pace at which companies are building new data centers means the bulk of the electricity to power them must come from fossil fuel-based power plants.”

Bashir’s analysis provides us with the smoking gun for solving the mystery of why the high-tech sector is now trying to kill climate science. Suddenly, Silicon Valley has a monetary reason for wanting to slow down the global movement to reduce the use of fossil fuels (no matter the cost of heating this planet to the boiling point), allying it with Big Oil in that regard. Scientists Michael E. Mann and Peter Hotez have analyzed this sort of billionaire-driven anti-intellectualism in their seminal new book Science Under Siege.

Turbocharging the Climate

One of Bill Gates’s half-truths is that there is good news about our climate progress and so no grounds for doomsaying. It certainly is true that we now have the levers to limit climate damage. That, however, doesn’t change our need to jolt the world aggressively with those very levers. The United Nations has recently concluded that we are indeed on a path to limit (if, under the circumstances, that’s even an adequate word for it) global heating to 2.8 degrees Celsius over the preindustrial average, if the countries of the world were to continue with their current policies, which reflect, however modestly, the global consensus that grew out of the 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change. Before that milestone, the world was marching toward an increase of 3.5º Celsius or more in the average surface temperature of the globe by 2100. The reduction in that projection, achieved over a decade, certainly represents genuine progress and should be celebrated, but the one thing it should not be used for (as Gates indeed does) is as an excuse for now slacking off.

The world’s peoples could shave another significant half a degree off that number if they simply met their Paris Agreement Nationally Determined Contributions, or NDCs. But even were they indeed to be faithful to their promises, we’re being taken inexorably toward at least a 2.3º Celsius global heat increase and, to put that in perspective, climate scientists worry that anything above 1.5º Celsius could ensure that the world’s climate will become devastatingly more chaotic. Imagine repeated Hurricane Melissas, far more turbocharged and striking not just islands in the Caribbean but, say, the U.S. Atlantic coast.

Just as we can’t afford to give in to a sense of doom, we can’t afford to be Pollyannas either. The news already isn’t good and we in the United States in the age of Donald Trump are now facing ever stronger headwinds against climate action. His Republican Party has, of course, enacted wide-ranging pro-carbon policies that will take effect next year and will also take pressure off China and the European Union to accelerate their paths to end the use of fossil fuels. Nor is it likely that the U.N. projections have truly reckoned with the coming proliferation of dirty data centers globally.

Worse yet, even before that hits, the world hasn’t found a way to get on a trajectory that is likely to truly decrease carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions substantially. In fact, the International Energy Agency has reported that “total energy-related CO2 emissions increased by 0.8% in 2024, hitting an all-time high of 37.8 Gt [gigatons] CO2.” In other words, we’re still putting more CO2 into the atmosphere in each succeeding year. It’s only the rate of increase that has slowed somewhat.

And that’s not the end of the bad news either. The 2.8-degree Celsius (5-degree Fahrenheit) increase toward which we’re still headed poses tremendous dangers. The numbers may not sound that dauntingly large, but remember, we’re talking about a global average of surface temperatures. If the average temperature goes up 5º F, that increase could translate into double-digit rises in places like Miami, Florida, and Basra, Iraq. And scientists now believe that, if cities with humidity levels of 80% experience a temperature of 122º F., that combination could be fatal to us humans.

Scientists have a formula for combining humidity and temperature, yielding what they call a “wet bulb” temperature. We cool off by sweating and letting the moisture evaporate from our skins, but that kind of heat and humidity would prevent such a cooling process from kicking in, which could mean that we humans would essentially be cooked to death.

And the danger won’t only be in places like the Gulf of Mexico and similar regions. As NASA warns, “Within 50 years, Midwestern states like Arkansas, Missouri, and Iowa will likely hit the critical wet-bulb temperature limit.” In short, significant parts of this planet could be turned into what might be thought of as the Hot Tub of Death. And with that comes, of course, the possibility of now almost inconceivable mega-storms, droughts, wildfires, and sea-level rise. It’s already projected that, by 2050, only 25 years from now, 200 million people annually will need humanitarian assistance to deal with an increasingly raging climate. That would be a billion people every decade.

Davy Jones’ Locker

In a sense, we’ve lucked out so far because until now so much carbon dioxide has been absorbed by the oceans and other carbon sinks on this planet. On the old, cold Earth of preindustrial times, half of the carbon dioxide produced went into the oceans or was absorbed on land by rainforests, chemical weathering, or rock formations. But the absorptive capacity of the oceans is now decreasing, which means that, if humanity continues to burn staggering quantities of fossil fuels and emit staggering amounts of CO2, we’ll overtax the capacity of the planet’s major carbon sink and ever more new carbon dioxide could then stay in the atmosphere, heating the globe for thousands of years.

The oceans absorb carbon dioxide in more than one way. Carbon dioxide mixes with cold sea water to form carbonic acid, which then splits into hydrogen and bicarbonate ions and the bicarbonate tends to stay in the water. More hydrogen, however, makes the oceans more acidic, which is not good for the marine life on which so many of us depend for food.

Some carbon is also used up by phytoplankton for photosynthesis, turning it into organic matter that is then eaten by other sea creatures and which also ultimately sinks to the ocean floor. But note that the oceans simply can’t take in infinite amounts of carbon dioxide. And if the increasing acidity of the ocean or its rising surface heat kill off a lot of phytoplankton, then their role in absorbing carbon will decline and ever more CO2 will stay in the atmosphere.

Some 90% of global heating is still absorbed by the world’s oceans, the surfaces of which are experiencing rapidly rising temperatures — and the hotter their surfaces get, the less carbon they can bury in Davy Jones’ locker because the water beneath them is growing ever more alkaline.

The Blue Screen of Death

Billionaire Bill Gates carps that a “doomsday outlook” is causing climate activists to “focus too much on near-term emissions goals.” Well, he’s wrong. The focus on near-term emissions goals comes from science. Gates doesn’t even mention the phrase “carbon budget” in his blog entry, which is telling.

After all, we are definitely in a race against time — and there’s no certainty that we’ll win. There is only so much carbon dioxide we can put into the atmosphere if we want to keep the increase in temperature under 1.5º C. And more than that is likely to cause weird, unexpected, and distinctly unpleasant changes in the world’s climate system. Unfortunately, as of 2025, we can only put 130 billion more tons of CO2 into the atmosphere and still meet that goal. At our current rate of emissions, we would use up that budget in — can you believe it? — just three years. What if we want to hold the line at 1.7º C? That budget would be exceeded in only nine years. So, the urgency climate activists feel in limiting short-term emissions derives from a knowledge that we’re rapidly depleting our carbon budget.

Most estimates are that, at current rates of emissions, we’ll use up the carbon budget for limiting warming to 2º C by 2050. Moreover, we will start losing a friend we had in that endeavor. The Earth’s biggest carbon sink, the oceans, will gradually cease being able to take up CO2 in the same quantities.

If cutting our use of fossil fuels means slowing (or even stopping) the rollout of AI data centers, inconveniencing Microsoft, Amazon, Google, and the rest of the crew, well, too bad. AI has its uses, but we clearly don’t need so much more of it desperately enough to thoroughly wreck our planet.

For a couple of decades, when I used a computer with Bill Gates’s Microsoft operating system, I would occasionally lose a day’s work because it abruptly crashed (through no fault of my own). We used to call that malfunction “the blue screen of death.” We don’t need the same thing to happen to the planet’s climate. As climate scientist Michael E. Mann has pointed out, once you’ve crashed this planet, unlike a computer, you won’t be able to reboot it.