SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

"It's pretty shocking, really, that we've lost that much biodiversity in such a short time," said one of the study authors.

A landmark study released Thursday in the journal Science found that the number of butterflies in the United States declined dramatically between 2000 and 2020.

"The prevalence of declines throughout all regions in the United States highlights an urgent need to protect butterflies from further losses," according to the abstract of the study, which was authored by over 30 researchers from around the country.

Between 2000 and 2020, total butterfly abundance in the contiguous United States fell by 22% across 554 recorded species. The study also reported widespread species-level decline, in addition to overall abundance decline. According to researchers, 13 times as many butterfly species are declining as they are increasing.

"It's pretty shocking, really, that we've lost that much biodiversity in such a short time," said Eliza Grames, a conservation biologist at Binghamton University in New York and one of the study authors, who spoke with WBUR about the findings.

The survey used data from multiple sources, including North American Butterfly Association, which is the "longest-running volunteer-based systematic count of butterflies in the world," as well as data from Massachusetts Butterfly Club, which "carries out organized field trips and records individuals' reports across the state in which participants identify and record butterflies seen."

Scientists and dedicated amateur enthusiasts helped collect the data, according to The Washington Post, which spoke with some of the researchers.

"Scientists could not get all the data we used," Nick Haddad, an ecologist and conservation biologist at Michigan State University who worked on the study, per the Post. "It took this incredible grassroots effort of people interested in nature."

The study identified pesticide use, climate change, and habitat loss as drivers of the decline.

The research echoes other scientific findings that have recorded widespread loss of insect abundance more generally, a phenomenon that's sometimes called the "insect apocalypse." Bugs do many important things, like pollinating crops and keeping soil healthy. "As insects become more scarce, our world will slowly grind to a halt, for it cannot function without them," wrote biologist Dave Goulson in 2021.

Entomologist David Wagner, who was not involved in the study, told the Post in an email that butterflies function as a "yardstick for measuring what is happening" among insects generally. He said the findings of the study were "catastrophic and saddening."

For agriculture as with energy, the real climate solutions are being silenced by the corporate cacophony.

I remember being filled with excitement when the Paris agreement to limit global warming to 1.5°C was adopted by nearly 200 countries at COP21. But after the curtains closed on COP29 last month—almost a decade later—my disenchantment with the event reached a new high.

As early as the 2010s, scientists from academia and the United Nations Environment Program warned that the U.S. and Europe must cut meat consumption by 50% to avoid climate disaster. Earlier COPs had mainly focused on fossil fuels, but meat and dairy corporations undoubtedly saw the writing on the wall that they too would soon come under fire.

Our food system needs to be sustainable for all—people, animals, and our planet.

Animal agriculture accounts for at least 14.5% of global greenhouse gas emissions, over quadruple the amount from global aviation. Global meat and dairy production have increased almost fivefold since the 1960s with the advent of industrialized agriculture. These factory-like systems are characterized by cramming thousands of animals into buildings or feedlots and feeding them unnatural grain diets from crops grown offsite. Even if all fossil fuel use was halted immediately, we would still exceed 1.5°C temperature rise without changing our food system, particularly our production and consumption of animal-sourced foods.

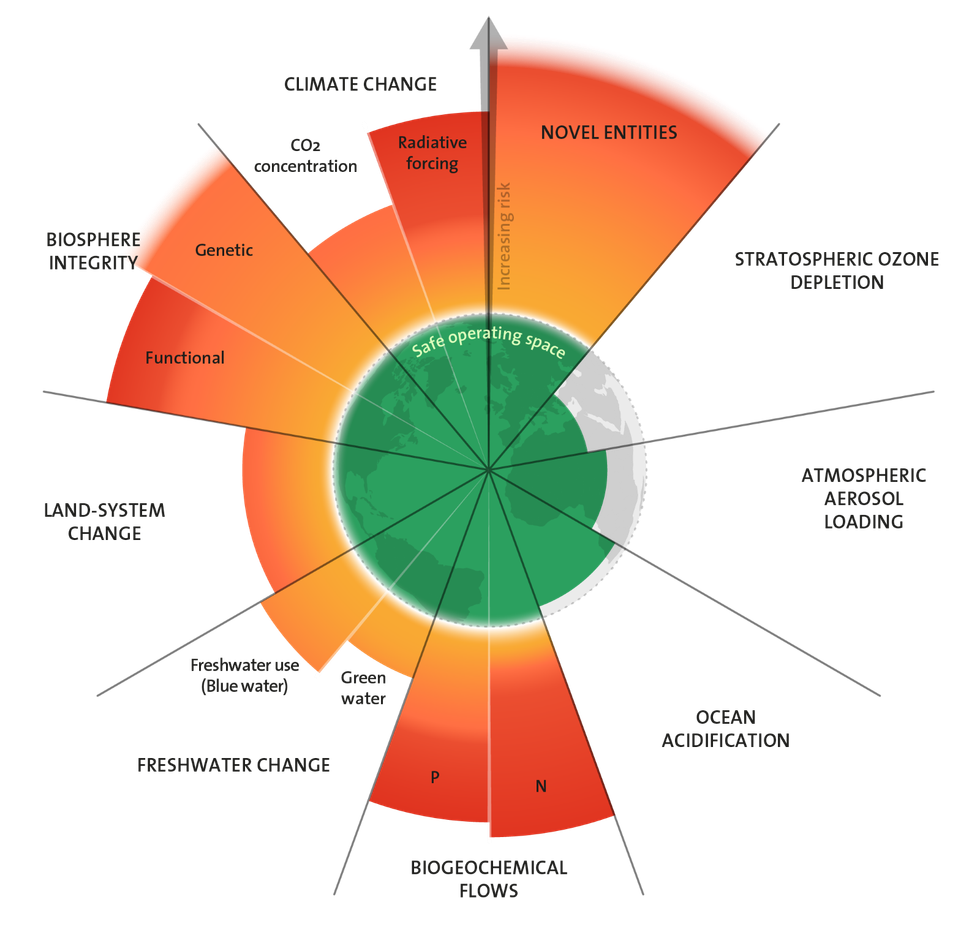

But climate change is just one of the threats we face. We have also breached five other planetary boundaries—biodiversity; land-use change; phosphorus and nitrogen cycling; freshwater use; and pollution from man-made substances such as plastics, antibiotics, and pesticides—all of which are also driven mainly by animal-sourced food production.

By the time world leaders were ready to consider our food system's impact on climate and the environment, the industrialized meat and dairy sector had already prepared its playbook to maintain the status quo. The Conference of Parties is meant to bring together the world's nations and thought leaders to address climate change. However, the event has become increasingly infiltrated by corporate interests. There were 52 delegates from the meat and dairy sector at COP29, many with country badges that gave them privileged access to diplomatic negotiations.

In this forum and others, the industry has peddled bombastic "solutions" under the guise of technology and innovation. Corporate-backed university research has lauded adding seaweed to cattle feed and turning manure lagoons the size of football fields into energy sources to reduce methane production. In Asia, companies are putting pigs in buildings over 20 stories tall, claiming the skyscrapers cut down on space and disease risks. And more recently, Bill Gates and Jeff Bezos started bankrolling research and development into vaccines that reduce the methane-causing bacteria found naturally in cows' stomachs. The industry hopes that the novelty and allure of new technologies will woo lawmakers and investors, but these "solutions" create more problems than they solve, exacerbating net greenhouse gas emissions, air and water pollution, wildlife loss, and freshwater depletion.

Emissions from animal-sourced foods can be broadly divided into four categories: ruminant fermentation (cow burps); manure; logistics (transport, packaging, processing, etc.); and land-use change, i.e., the conversion of wild spaces into pasture, feedlots, and cropland for feed. In the U.S., ruminant fermentation and manure emit more methane than natural gas and petroleum systems combined.

A new report found that beef consumption must decline by over a quarter globally by 2035 to curb methane emissions from cattle, which the industry's solutions claim to solve without needing to reduce consumption. But the direct emissions from cattle aren't the only problem—beef and dairy production is also the leading driver of deforestation, which must decline by 72% by 2035, and reforestation must rise by 115%. About 35% of habitable land is used to raise animals for food or to grow their feed (mostly corn and soy), about the size of North and South America combined.

Put simply, the inadequate solutions put forth by Big Ag cannot outpace industrialized farming's negative impacts on the planet. While seaweed and methane vaccines may address cow burps, they don't address carbon emissions from deforestation or manure emissions of nitrous oxide, a greenhouse gas over 270 times more powerful than CO2. They also don't address the nitrate water pollution from manure, which can sicken people and cause massive fish kills and harmful algal blooms; biodiversity decline from habitat loss, which has dropped 73% since the rise of industrialized animal agriculture; freshwater use, drying up rivers and accounting for over a quarter of humanity's water footprint; or pesticide use on corn and soy feed, which kills soil microorganisms that are vital to life on Earth.

Skyscrapers, while solving some land-use change, do not consider the resources and the land used to grow animal feed, which is globally about equivalent to the size of Europe. They also don't address the inherent inefficiencies with feeding grain to animals raised for food. If fed directly to people, those grains could feed almost half the world's population. And while the companies using pig skyscrapers claim they enhance biosecurity by keeping potential viruses locked inside, a system failure could spell disaster, posing a bigger threat to wildlife and even humans.

We need both a monumental shift from industrialized agriculture to regenerative systems and a dramatic shift from animal-heavy diets to diets rich in legumes, beans, vegetables, fruits, and whole grains, with meat and dairy as a specialty rather than a staple.

One solution that is gaining traction as an alternative to Big Ag's proposals is regenerative grazing. When done right, regenerative grazing eliminates the need for pesticides and leans into the natural local ecology, putting farm animals onto rotated pastures and facilitating carbon uptake into the soil. Regenerative animal agriculture is arguably the only solution put forward that addresses all six breached planetary boundaries as well as animal welfare and disease risk, and studies suggest it can improve the nutritional quality of animal-sourced foods. While it is imperative to transition from industrialized to regenerative systems, regenerative grazing comes with major caveats. This type of farming is only beneficial in small doses—cutting down centuries-old forests or filling in carbon-rich wetlands to make way for regenerative pastures would do much more climate and ecological harm than good. Soil carbon sequestration takes time and increases with vegetation and undisturbed soil, meaning that any regenerative pastures made today will never be able to capture as much carbon as the original natural landscape, especially in forests, mangroves, wetlands, and tundra. And while regenerative farmlands create better wildlife habitats than feedlots and monocultures, they still don't function like a fully natural ecosystem and food web. Also, cattle emit more methane than their native ruminant counterparts such as bison and deer.

Most notably, however, we simply don't have enough land to produce regeneratively raised animal products at the current consumption rate. Regenerative grazing requires more land than industrialized systems, sometimes two to three times more, and as mentioned the livestock industry already occupies over one-third of the world's habitable land. In all, we have much more to gain from rewilding crop- and rangeland than from turning the world into one big regenerative pasture.

All this brings us to one conclusion—the one that was made by scientists over a decade ago: We need to eat less meat. As Action Aid's Teresa Anderson noted at this year's COP, "The real answers to the climate crisis aren’t being heard over the corporate cacophony."

Scientific climate analyses over the last few years have been grim at best, and apocalyptic at worst. According to one of the latest U.N. reports, limiting global temperature rise to 1.5°C (2.7°F) requires cutting greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 57% by 2035, relative to 2023 emissions. However, current national policies—none of which currently include diet shifts—will achieve less than a 1% reduction by 2035. If the 54 wealthiest nations adopted sustainable healthy diets with modest amounts of animal products, they could slash their total emissions by 61%. If we also allowed the leftover land to rewild, we could sequester 30% of our global carbon budget in these nations and nearly 100% if adopted globally.

Our food system needs to be sustainable for all—people, animals, and our planet. Quick fixes and bandages will not save our planet from climate change, biodiversity loss, and pollution. We need both a monumental shift from industrialized agriculture to regenerative systems and a dramatic shift from animal-heavy diets to diets rich in legumes, beans, vegetables, fruits, and whole grains, with meat and dairy as a specialty rather than a staple. As nations draft their policies for COP30, due early this year, we need leaders to adopt real food system solutions instead of buying into the corporate cacophony.

What consequences will these massive renewable energy projects have on biodiversity and the wild creatures that depend on these lands for survival?

Like many roads that cut through Wyoming, the highway into the town of Rawlins is a long, winding one surrounded by rolling hills, barbed wire fences, and cattle ranches. I’d traveled this stretch of Wyoming many times. Once during a dangerous blizzard, another time during a car-rattling thunderstorm, the rain so heavy my windshield wipers couldn’t keep pace with the deluge. The weather might be wild and unpredictable in Wyoming’s outback, but the people are friendly and welcoming as long as you don’t talk politics or mention that you live in a place like California.

One late summer afternoon on a trip at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, I stopped off in Rawlins for lunch. There wasn’t a mask in sight, never mind any attempt at social distancing. Two men sat in a booth right behind me, one in a dark suit and the other in overalls, who struck me as a bit of an odd couple. Across from them were an older gentleman and his wife, clearly Rawlins locals. They wondered what those two were up to.

“Are you guys here to work on that massive wind farm?” asked the husband, who clearly had spent decades in the sun. He directed his question to the clean-cut guy in the suit with a straight mustache. His truck, shiny and spotless, was visible out the window, a hardhat and clipboard sitting on the dashboard.

“Yes, we’ll be in and out of town for a few years if things go right. There’s a lot of work to be done before it’s in working order. We’re mapping it all out,” the man replied.

“Well, at least we’ll have some clean energy around here,” the old man said, chuckling. “Finally, putting all of this damned wind to work for once!”

I ate my sandwich silently, already uncomfortable in a restaurant for the first time in months.

“There will sure be a lot of wind energy,” the worker in overalls replied. “But none of it’s for Wyoming.” He added that it would all be directed to California.

“What?!” exclaimed the man as his wife shook her head in frustration. “Commiefornia?! That’s nuts!”

Should Wyoming really be supplying California with wind energy when that state already has plenty of windy options?

Right-wing hyperbole aside, he had a point: It was pretty crazy. Projected to be the largest wind farm in the country, it would indeed make a bundle of electricity, just not for transmission to any homes in Rawlins. The power produced by that future 600-turbine, 3,000 MW Chokecherry and Sierra Madre wind farm, with its $5-billion price tag, won’t, in fact, flow anywhere in Colorado, even though it’s owned by the Denver-based Anschutz Corporation. Instead, its electricity will travel 1,000 miles southwest to exclusively supply residents in Southern California.

The project, 17 years in the making and spanning 1,500 acres, hasn’t sparked a whole lot of opposition despite its mammoth size. This might be because the turbines aren’t located near homes, but on privately owned cattle ranches and federal lands managed by the Bureau of Land Management. Aside from a few raised eyebrows and that one shocked couple, not many people in Rawlins seemed all that bothered. Then again, Rawlins doesn’t have too many folks to bother (population 8,203).

Wyoming was once this country’s coal-mining capital. Now, with the development of wind farms, it’s becoming a major player in clean energy, part of a significant energy transition aimed at reducing our reliance on fossil fuels.

Even so, Phil Anschutz, whose company is behind the Chokecherry and Sierra Madre wind farms, didn’t get into the green energy game just to save the climate. “We’re doing it to make money,” admits Anschutz, who got the bulk of his billion-dollar fortune from the oil industry. With California’s mandate to end its reliance on fossil fuels by 2045, he now sees a profitable opportunity, and he’s pulling Wyoming along for the ride.

Since 1988, Wyoming has been the country’s top coal-producing state, but its mining has declined steeply over the past 15 years, as has coal mining more generally in the U.S. where 40% of coal plants are set to be shuttered by 2030. In addition to the closed plants, the downturn in coal output has resulted largely from cheap natural gas prices and the influx of utility-scale renewable energy projects. Wyoming’s coal production peaked in 2008, churning out more than 466 million short tons. Today, its mines produce around 288 million short tons of coal, accounting for 40% of America’s total coal mining and supplying around 25% of its power generation. Coal plants are also responsible for more than 60% of carbon dioxide emissions from the country’s power sector. As far as the climate is concerned, that’s still way too much.

The good news is that the U.S. has witnessed a dramatic drop in daily coal use, down 62% since 2008, and few places have felt coal’s rapid decline more than Wyoming, where a green shift is distinctly afoot. Despite being one of the country’s most conservative states (71% of its voters backed U.S. President-elect Donald Trump this year), Wyoming is going all in on wind energy. In 2023, wind comprised 21% of Wyoming’s net energy generation, with 3,100 megawatts, or enough energy to power more than 2.5 million homes. That’s up from 9.4% in 2007.

On the surface, Wyoming’s transition from coal to wind is laudable and entirely necessary. When it comes to carbon emissions, coal is by far the nastiest of the fossil fuels. If climate chaos is to be mitigated in any way, coal will have to become a thing of the past and wind will provide a far cleaner alternative. Even so, wind energy has faced its fair share of pushback. A major criticism is that wind farms, like the one outside Rawlins, are blights on the landscape. Even if folks in Rawlins aren’t outraged by the huge wind farm on the outskirts of town, not everyone is on board with Wyoming’s wind rush.

“We don’t want to ruin where we live,” says Sue Jones, a Republican commissioner of Carbon County. “We can call it renewable, we can call it green, but green still has a downside. With wind, it’s visual. We don’t want to destroy one environment to save another.”

Energy from the Chokecherry and Sierra Madre wind farms will also reach California via a 732-mile transmission line known as the “TransWest Express,” which will feed solar and wind energy to parts of Arizona and Nevada as well. To be completed by 2029, the $3-billion line will travel through four states on public and private land and has been subject to approval by property owners; tribes; and state, federal, and local agencies. The TransWest Express passed the final review process in April 2023 and will become the most extensive interstate transmission line built in the U.S. in decades. As one might imagine, the infrastructure and land required to construct the TransWest Express will considerably impact local ecology. As for the Chokecherry and Sierra Madre wind farm, it might not encroach on residential neighborhoods, but it does risk destroying some of the best natural wildlife habitats in Wyoming.

Transmission towers connecting thick high-voltage power lines will stand 180 feet tall, slicing through prime sage-grouse, elk, and mule deer habitat and Colorado’s largest concentration of low-elevation wildlands. The TransWest Express will pass over rivers and streams, chop through forests, stretch over hills, and bulldoze its way through scenic valleys. Many believe this is just the price that must be paid to combat our warming climate and that the impact of the Chokecherry and Sierra Madre projects, and the TransWest Express, will be nothing compared to what unmitigated climate chaos will otherwise reap. Some disagree, however, and wonder if such expansive wind farms are really the best we can come up with in the face of climate change.

“This question puts a fine point on the twin looming disasters that humanity has brought upon the Earth: the climate crisis and the biodiversity crisis,” argues Erik Molvar, a wildlife biologist and executive director of the Western Watersheds Project, a Hailey, Idaho-based environmental group. “The climate crisis and the biodiversity crisis are of equal importance to humans and every other species with which we share this globe, and it would be foolhardy to ignore either in pursuit of solutions for the other.”

Molver is onto something often overlooked in discussions and debates around our much-needed energy transition: What consequences will these massive renewable energy projects have on biodiversity and the wild creatures that depend on these lands for survival?

Biologists like Mike Lockhart, who worked for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) for more than 30 years, claim that these large wind farms are more than just an eyesore and will negatively affect wildlife in Wyoming. Raptors, eagles, passerines, bats, and various migrating birds frequently collide with the blades, which typically span 165 feet.

“Most of the [Wyoming wind energy] development is just going off like a rocket right now, and we already have eagles that are getting killed by wind turbines—a hell of a lot more than people really understand,” warns Lockhart, a highly respected expert on golden eagles.

In a recent conversation with Dustin Bleizeffer, a writer for WyoFile, Lockhart warned that wind energy development in Wyoming, in particular, is occurring at a higher rate than environmental assessments can keep up with, which means it could be having damning effects on wild animals. Places with consistent winds, as Lockhart explains, also happen to be prime wildlife habitats, and most of the big wind farms in Wyoming are being built before we know enough about what their impact could be on bird populations.

The Department of Energy projects that wind will generate an impressive 35% of the country’s electricity generation by 2050. If so, upwards of 5 million birds could be killed by wind turbines every year.

In February 2024, FWS updated its permitting process under the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act, hoping it would help offset some of wind energy’s effects on eagles. The new rules, however, will still allow eagles to die. The new permits for wind turbines won’t even specify the number of eagles allowed to be killed and companies won’t, in fact, be out of compliance even if their wind turbines are responsible for injuring or killing significant numbers of them.

Teton Raptor Center Conservation Director Bryan Bedrosian believes that golden eagle populations in Wyoming are indeed on the decline as such projects only grow and habitats are destroyed—and the boom in wind energy, he adds, isn’t helping matters. “We have some of the best golden eagle populations in Wyoming, but it doesn’t mean the population is not at risk,” he says. “As we increase wind development across the U.S., that risk is increasing.”

It appears that a few politicians in Washington are listening. In October, Reps. Jared Huffman (D-Calif.) and Brian Fitzpatrick (R-Penn.) introduced a bipartisan bill updating the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918. The legislation would authorize penalties of up to $10,000 per violation for harm to birds. Still, congressional staffers tell me it’s unlikely to pass, given the quiet lobbying efforts behind the scenes by a motley crew of oil, gas, and wind energy developers.

The Department of Energy projects that wind will generate an impressive 35% of the country’s electricity generation by 2050. If so, upwards of 5 million birds could be killed by wind turbines every year. In addition to golden eagles, the American Bird Conservancy notes that “Yellow-billed Cuckoos, Golden-winged Warblers, and Kirtland’s Warblers are particularly vulnerable. Wind energy poses special risks to endangered or threatened species such as Whooping Cranes and California Condors, since the loss of even a few individuals can have population-level effects.”

And bird kills aren’t the only problem either. The constant drone of the turbines can also impact migration patterns, and the larger the wind farm, the more habitat is likely to be wrecked. The key to reducing such horrors is to try to locate wind farms as far away from areas used as migratory corridors as possible. But as Lockhart points out, that’s easier said than done, as places with steady winds also tend to be environments that traveling birds utilize.

Even though onshore wind farms kill birds and can disrupt habitats, most scientists believe that wind energy must play a role in the world’s much-needed energy transition. Mark Z. Jacobson, author of No Miracles Needed and director of the Atmosphere/Energy Program at Stanford University, notes that the minimal carbon emissions in the life-cycle of onshore wind energy are only outmatched by the carbon footprint of rooftop solar. It would be extremely difficult, he points out, to curtail the world’s use of fossil fuels without embracing wind energy.

Scientists are, however, devising novel ways to reduce the collisions that cause such deaths. One method is to paint the blades of the wind turbines black to increase their visibility. A recent study showed that doing so instantly reduces bird fatalities by 70%.

Such possibilities are promising, but shouldn’t wind project creators also do as much as possible to site their energy projects as close to their consumers as they can? Should Wyoming really be supplying California with wind energy when that state already has plenty of windy options—in and around Los Angeles, for example, on thousands of acres of oil and brownfield sites that are quite suitable for wind or solar farms and don’t risk destroying animal habitats by constructing hundreds of miles of power lines?

Wind energy from Wyoming will not finally reach California until the end of the decade. As Phil Anschutz reminds us, it’s all about money, and land in Los Angeles, however battered and bruised, would still be a far cheaper and less destructive way to go than parceling out open space in Wyoming.

In that roadside cafe in Rawlins, the two workers paid their bill and left. I sat there quietly, wondering what that couple made of the revelation that the wind farm nearby wasn’t going to benefit them. Finally, nodding toward the men’s truck as it drove away, I asked, “What do you think of that?”

“Same old, same old,” the guy eventually replied. “Reminds me of the coal industry, the oil industry, you name it. The big city boys come and take our resources and we end up having little to show for it.”

Shortly after lunch, I left Rawlins and made my way two hours north to the Pioneer Wind Farm near the little town of Glenrock that began operating in 2011. I pulled over to get some fresh air and stretch my legs. As I exited the car, I could hear the steady hum of turbines slicing through the air above me and I didn’t have to walk very far before I nearly stepped on a dead hawk in the early stages of decay. I had no way of knowing how the poor critter was killed, but it was hard to imagine that the hulking blade swirling overhead didn’t have something to do with it.