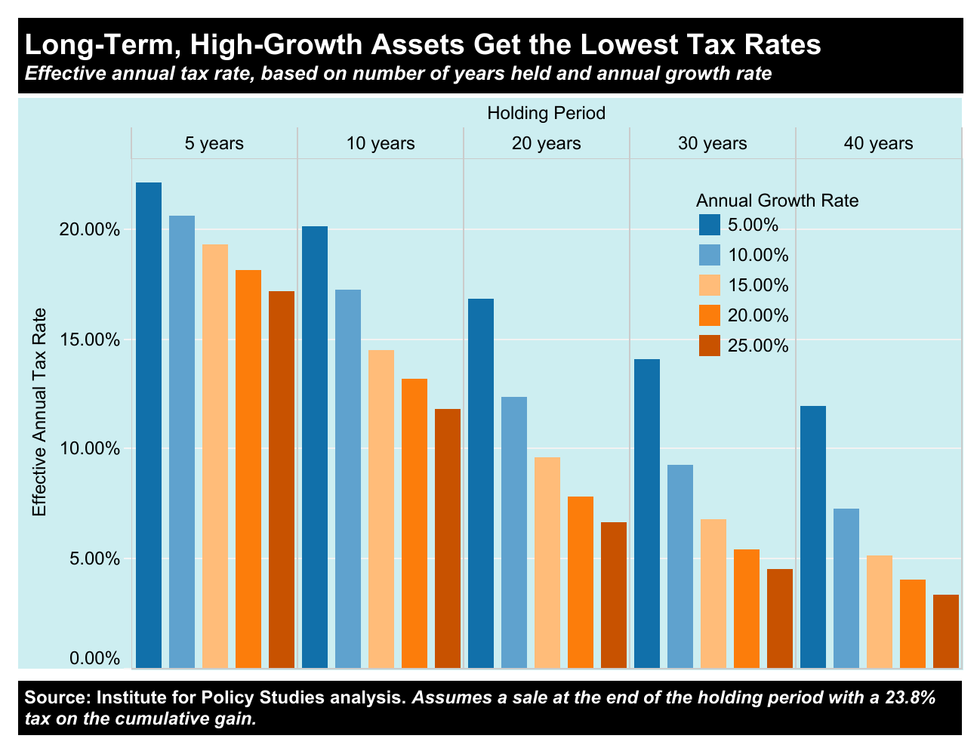

Eliminating the preferential rate for capital gains, many analysts maintain, would finally place investment income and wages on an equal footing tax-wise. But would that actually be the case? Unfortunately, no. Simply equalizing the basic tax rates on ordinary and capital gains income would leave in place the gaping “buy-hold for decades-sell” loophole.

If you had to choose between paying tax at 10% annually or paying 10% every 10 years, would you consider those two rates equal?

The framing of the debate over the current preferential treatment for capital gains makes this loophole quite difficult to notice. And that same framing leaves us accepting, incorrectly, the implied premise that the low nominal tax rate rich investors pay on their capital gains—barely half the rate applicable to other types of income—accurately describes the tax rate in an economic sense.

If we continue to focus solely on whether the 20% rate applied to billionaire gains should be raised to 37%, in other words, we won’t be questioning that accuracy.

A similar phenomenon arises when we’re discussing billionaire wealth. Most of us see the obscene fortunes of the world’s billionaires, as reported by Forbes and Bloomberg, and seldom consider the possibility that many of those fortunes may actually be higher than the published estimates. But think a moment: If you held a billion-dollar fortune and wanted to keep your tax bill as low as possible, would you want policymakers knowing the full extent of your wealth? Of course not.

But most of the rest of us don’t ask that question. We see a deep pocket’s wealth estimated at, say, $50 billion—about 50,000 times more than our own $100,000 net worth—and the last thought to enter our minds would be that this deep pocket’s wealth might really stand at $75 billion.

Just as the bloated level of estimates of billionaire fortunes causes us not to consider the possibility those fortunes may be actually even larger, the low tax rate nominally applicable to capital gains income leaves us unlikely to fully compare tax rates on ordinary and capital gains income.

The key to understanding how to make better comparisons: taking tax frequency into account.

Most of the income Americans make—wages and salaries, most notably—gets taxed annually. Capital gains, by contrast, get taxed only when the holders of investment assets decide to sell them. That reality turns a simple comparison of the 20% tax rate on capital gains with the 37% top tax rate on ordinary income into an apples-to-oranges comparison.

Or to put things another way: If you had to choose between paying tax at 10% annually or paying 10% every 10 years, would you consider those two rates equal?

We can overcome the difficulty in comparing the tax rates on ordinary and capital gains income once we begin to understand why we cannot consider these two situations the same.

Consider, for starters, what your tax liability would be if you inadvertently understated your income from a small business on your tax return by $50,000 and then reported the missing income three years later. You would end up paying the IRS not just the tax you should have paid on that income, but an interest charge as well—for deferring the payment of tax beyond the year you earned your income.

For the sake of discussion, let’s say you were required to pay $10,000 in tax and $2,500 in interest. You would then have paid tax at an overall 20% rate.

Now compare that to the situation your rich friend encountered. She invested $50,000 in stocks and held that investment for four years. Say that investment doubled in value, to $100,000, in the first year—the same year you earned the $50,000 of income you failed to report—and then held that value for another three years. If your friend then sold her investment and paid tax at the 20% rate applicable to capital gains, she could claim to have paid tax at the same 20% rate you did.

But would that be accurate? Not really. Economically, your friend has obviously paid tax at a lower rate than you. Yes, you both realized $50,000 of income in the same year and you both paid tax on that income three years later. But you paid a total of $12,500, including interest, while she paid only $10,000.

What happened here? Economically, your friend’s $10,000 tax payment includes a charge for the privilege of deferring the payment of tax. By contrast, our tax system considers your $2,500 deferral charge on your $10,000 obligation a separate item. To make the comparison apples-to-apples, then, we might consider your friend to have paid tax at an effective annual rate of 16%, $8,000, plus a $2,000 deferral fee.

Now consider the case where you received your $50,000 of income—along with additional income necessary to place you in the top marginal tax bracket—in the same year your friend sold her $50,000 investment for $100,000, rather than the year she purchased it.

You would have paid tax on your $50,000 at the marginal rate of 37%, a total of $18,500—and likely have been laser-focused on having had to pay nearly double the tax rate that your ultra-rich friend paid–37% versus 20%—on the same $50,000 of income. In all likelihood, you would at the same time have failed to focus on the reality that the 20% rate applied to your friend’s gain actually overstated the rate she paid in comparison to the rate you paid.

Let’s expand our financial horizon. Say a rich investor purchases an asset for $1 million. Over the next 30 years, that asset grows in value at a steady pace of 10% per year, an average-ish return for a rich American investor. At the end of the 30 years, the asset would be worth about $17,450,000. If the investor then sold the asset and paid tax at 20% on the $16,450,000 gain, a total tax of $3,290,000, he would be left with about $14,160,000.

Suppose instead our investor had to pay tax annually on each year’s investment gains at the rate of just 7.65%. Suppose our investor each year sold a portion of the investment sufficient to pay the tax liability. At the end of the 30 years, the investor will have paid a total of $1,090,000 in tax and be left with the same amount, $14,160,000, that he would have been left with after paying tax at 20% upon a sale in year 30.

Why the $2,200,000 difference between the $3,290,000 total paid when taxed in year 30 and the $1,090,000 total paid when taxed annually? In economic terms, that’s what the investor paid for the privilege of not paying tax until year 30. In other words, interest.

Removing what economically amounts to a charge for the privilege of deferring tax allows us to make an apples-to-apples comparison. The investor effectively has paid tax at a rate of 6.63%. That’s a 30.37 percentage-point difference between the investor’s effective rate of tax and the 37% top tax rate on ordinary income.

How much would that 30.37 percentage-point gap be reduced if the investor’s $16.45 million gain were taxed at a 37% rate when he sold his investment after 30 years? About five percentage points. Of the investor’s 37% nominal tax rate—using the same method of analysis—about 25.34 percentage points would constitute interest, leaving only 11.66 percentage points, economically, as tax.

Should we equalize the tax rates applicable to capital gains and ordinary income? Absolutely. But let’s not kid ourselves. Making that change will not remotely eliminate the preferential tax treatment accorded to capital gains. We need a further change, at least for the billionaire class.

The Billionaires Income Tax proposal that Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) introduced last year would require billionaires to pay tax annually on the growth in their wealth—in the same way the rest of us pay tax on our salaries and wages. It’s high time to close the “buy-hold for decades-sell” loophole. Sen. Wyden’s Billionaires Income Tax would be one way to do just that.