3 Ways the US Refuses to Play by Global Rules

In keeping Guantánamo open, continuing to use illegal weapons, and dragging its feet on climate action, this country has stood out from the crowd in a sadly malevolent fashion.

In 1963, the summer I turned 11, my mother had a gig evaluating Peace Corps programs in Egypt and Ethiopia. My younger brother and I spent most of that summer in France. We were first in Paris with my mother before she left for North Africa, then with my father and his girlfriend in a tiny town on the Mediterranean. (In the middle of our six-week sojourn there, the girlfriend ran off to marry a Czech she’d met, but that’s another story.)

In Paris, I saw American tourists striding around in their shorts and sandals, cameras slung around their necks, staking out positions in cathedrals and museums. I listened to my mother’s commentary on what she considered their boorishness and insensitivity. In my 11-year-old mind, I tended to agree. I’d already heard the expression “the ugly American”—although I then knew nothing about the prophetic 1958 novel with that title about U.S. diplomatic bumbling in Southeast Asia in the midst of the Cold War—and it seemed to me that those interlopers in France fit the term perfectly.

When I got home, I confided to a friend (whose parents, I learned years later, worked for the CIA) that sometimes, while in Europe, I’d felt ashamed to be an American. “You should never feel that way,” she replied. “This is the best country in the world!”

In this century, in many important ways, the United States has become an outlier and, in some cases, even an outlaw.

Indeed, the United States was, then, the leader of what was known as “the free world.” Never mind that, throughout the Cold War, we would actively support dictatorships (in Argentina, Chile, Indonesia, Nicaragua, and El Salvador, among other places) and actually overthrow democratizing governments (in Chile, Guatemala, and Iran, for example). In that era of the G.I. Bill, strong unions, employer-provided healthcare, and general postwar economic dominance, to most of us who were white and within reach of the middle class, the United States probably did look like the best country in the world.

Things do look a bit different today, don’t they? In this century, in many important ways, the United States has become an outlier and, in some cases, even an outlaw. Here are three examples of U.S. behavior that has been literally egregious, three ways in which this country has stood out from the crowd in a sadly malevolent fashion.

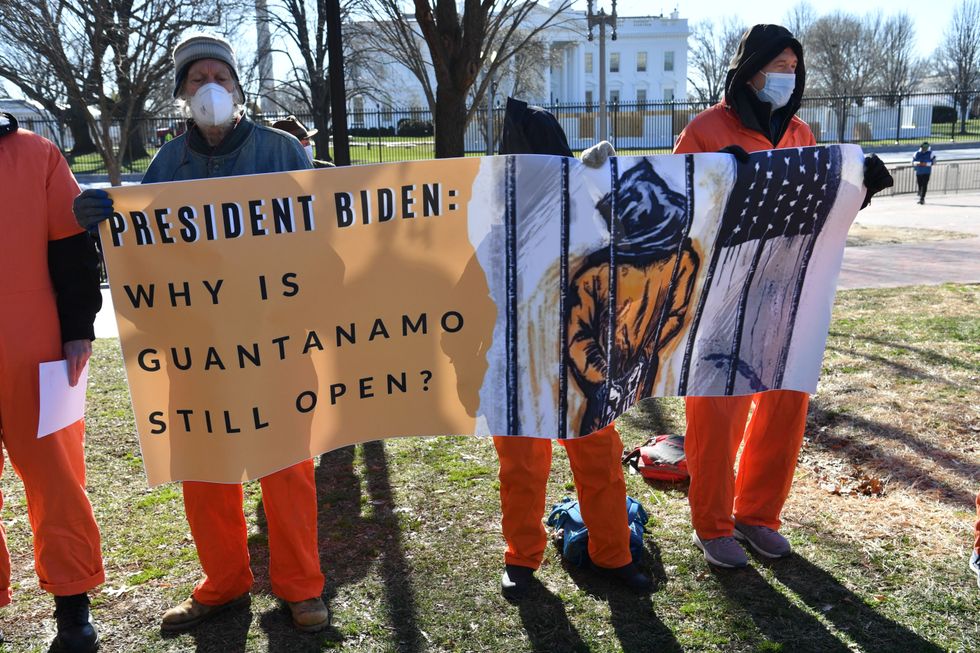

Guantánamo, the Forever Prison Camp

Demonstrators hold a sign during a protest calling for the closure of Guantánamo in front of the White House in Washington, D.C. on January 11, 2022.

(Photo: Nicholas Kamm/AFP via Getty Images)In January 2002, the administration of President George W. Bush established an offshore prison camp at the U.S. Naval Base in Guantánamo Bay, Cuba. The idea was to house prisoners taken in what had already been labelled “the Global War on Terror” on a little piece of “U.S.” soil beyond the reach of the American legal system and whatever protections that system might afford anyone inside the country. (If you wonder how the United States had access to a chunk of land on an island nation with which it had the frostiest of relations, including decades of economic sanctions, here’s the story: In 1903, long before Cuba’s 1959 revolution, its government had granted the United States “coaling” rights at Guantánamo, meaning that the U.S. Navy could establish a base there to refuel its ships. The agreement remained in force in 2002, as it does today.)

In the years that followed, Guantánamo became the site of the torture and even murder of individuals the U.S. took prisoner in Afghanistan, Iraq, and other countries ranging from Pakistan to Mauritania. Having written for more than 20 years about such U.S. torture programs that began in October 2001, I find today that I can’t bring myself to chronicle one more time all the horrors that went on at Guantánamo or at CIA “black sites” in countries ranging from Thailand to Poland, or at Bagram Air Base in Afghanistan, or indeed at the Abu Ghraib prison and Camp NAMA (whose motto was: “No blood, no foul”) in Iraq. If you don’t remember, just go ahead and google those places. I’ll wait.

Thirty men remain at Guantánamo today. Some have never been tried. Some have never even been charged with a crime. Their continued detention and torture, including, as recently as 2014, punitive, brutal forced feeding for hunger strikers, confirmed the status of the United States as a global scofflaw. To this day, keeping Guantánamo open displays this country’s contempt for international law, including the Geneva Conventions and the United Nations Convention against Torture. It also displays contempt for our own legal system, including the Constitution’s “supremacy” clause which makes any ratified international treaty like the Convention against Torture “the supreme law of the land.”

In February 2023, Fionnuala Ní Aoláin, the U.N.’s Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms while countering terrorism, became the first representative of the United Nations ever permitted to visit Guantánamo. She was horrified by what she found there, tellingThe Guardian that the U.S. has

“a responsibility to redress the harms it inflicted on its Muslim torture victims. Existing medical treatment, both at the prison camp in Cuba and for detainees released to other countries, was inadequate to deal with multiple problems such as traumatic brain injuries, permanent disabilities, sleep disorders, flashbacks, and untreated post-traumatic stress disorder.”

“These men,” she added, “are all survivors of torture, a unique crime under international law, and in urgent need of care. Torture breaks a person, it is intended to render them helpless and powerless so that they cease to function psychologically, and in my conversations both with current and former detainees I observed the harms it caused.”

The lawyer for one tortured prisoner, Ammar al-Baluchi, reports that al-Baluchi “suffers from traumatic brain injury from having been subjected to ‘walling’ where his head was smashed repeatedly against the wall.” He has entered a deepening cognitive decline, whose “symptoms include headaches, dizziness, difficulty thinking and performing simple tasks.” He cannot sleep for more than two hours at a time, “having been sleep-deprived as a torture technique.”

The United States, Ní Aoláin insists, must provide rehabilitative care for the men it has broken. I have my doubts, however, about the curative powers of any treatment administered by Americans, even civilian psychologists. After all, two of them personally designed and implemented the CIA’s torture program.

The United States should indeed foot the bill for treating not only the 30 men who remain in Guantánamo, but others who have been released and continue to suffer the long-term effects of torture. And of course, it goes without saying that the Biden administration should finally close that illegal prison camp—although that’s not likely to happen. Apparently it’s easier to end an entire war than decide what to do with 30 prisoners.

Unlawful Weapons

This photo taken on July 15, 2023 shows a view of Qala-e-Shatir village, where the U.S. forces dropped cluster bombs in 2001, in Herat City of west Afghanistan's Herat province.

(Photo: Mashal/Xinhua via Getty Images)

The United States is an outlier in another arena as well: the production and deployment of arms widely recognized as presenting an immediate or future danger to non-combatants. The U.S. has steadfastly resisted joining conventions outlawing such weaponry, including cluster bombs (or more euphemistically, “cluster munitions”) and landmines.

In fact, the United States deployed cluster bombs in its wars in Iraq, and Afghanistan. (In the previous century, it dropped 270 million of them in Laos alone while fighting the Vietnam War.) Ironically—one might even say, hypocritically—the U.S. joined 146 other countries in condemning Syrian and Russian use of the same weapons in the Syrian civil war. Indeed, former White House press secretary Jen Psaki told reporters that if Russia were using them in Ukraine (as, in fact, it is), that would constitute a “war crime.”

Now the U.S. has sent cluster bombs to Ukraine, supposedly to fill a crucial gap in the supply of artillery shells. Mind you, it’s not that the United States doesn’t have enough conventional artillery shells to resupply Ukraine. The problem is that sending them there would leave this country unprepared to fight two simultaneous (and hypothetical) major wars as envisioned in what the Pentagon likes to think of as its readiness doctrine.

What are cluster munitions? They are artillery shells packed with many individual bomblets, or “submunitions.” When one is fired, from up to 20 miles away, it spreads as many as 90 separate bomblets over a wide area, making it an excellent way to kill a lot of enemy soldiers with a single shot.

They can, in other words, lie in wait long after a war is over, sowing farmland and forest with deadly booby traps.

What places these weapons off-limits for most nations is that not all the bomblets explode. Some can stay where they fell for years, even decades, until as a New York Times editorial put it, “somebody—often, a child spotting a brightly colored, battery-size doodad on the ground—accidentally sets it off.” They can, in other words, lie in wait long after a war is over, sowing farmland and forest with deadly booby traps. That’s why then-Secretary General of the United Nations Ban Ki-moon once spoke of “the world’s collective revulsion at these abhorrent weapons.” That’s why 123 countries have signed the 2008 Convention on Cluster Munitions. Among the holdouts, however, are Russia, Ukraine, and the United States.

According to National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan, the cluster bombs the U.S. has now sent to Ukraine each contains 88 bomblets, with, according to the Pentagon, a failure rate of under 2.5%. (Other sources, however, suggest that it could be 14% or higher.) This means that for every cluster shell fired, at least two submunitions are likely to be duds. We have no idea how many of these weapons the U.S. is supplying, but a Pentagon spokesman in a briefing said there are “hundreds of thousands available.” It doesn’t take much mathematical imagination to realize that they present a real future danger to Ukrainian civilians. Nor is it terribly comforting when Sullivan assures the world that the Ukrainian government is “motivated” to minimize risk to civilians as the munitions are deployed, because “these are their citizens that they’re protecting.”

I for one am not eager to leave such cost-benefit risk calculations in the hands of any government fighting for its survival. That’s precisely why international laws against indiscriminate weapons exist—to prevent governments from having to make such calculations in the heat of battle.

Cluster bombs are only a subset of the weapons that leave behind “explosive remnants of war.” Landmines are another. Like Russia, the United States is not found among the 164 countries that have signed the 1999 Ottawa Convention, which required signatories to stop producing landmines, destroy their existing stockpiles, and clear their own territories of mines.

Ironically, the U.S. routinely donates money to pay for mine clearance around the world, which is certainly a good thing, given the legacy it left, for example, in Vietnam. According to The New York Times in 2018:

“Since the war there ended in 1975, at least 40,000 Vietnamese are believed to have been killed and another 60,000 wounded by American land mines, artillery shells, cluster bombs, and other ordnance that failed to detonate back then. They later exploded when handled by scrap-metal scavengers and unsuspecting children.”

Hot Enough for Ya?

A tourist is wearing a towel on his head o protect from the sun during a heat wave on July 25, 2023 in Athens, Greece.

(Photo: Nikolas Kokovlis/NurPhoto via Getty Images)

As I write this piece, about one-third of this country’s population is living under heat alerts. That’s 110 million people. A heatwave is baking Europe, where 16 Italian cities are under warnings, and Greece has closed the Acropolis to prevent tourists from dying of heat stroke. This summer looks to be worse in Europe than even last year’s record-breaker when heat killed more than 60,000 people. In the U.S., too, heat is by far the greatest weather-related killer. Makes you wonder why Texas Governor Greg Abbott signed a bill eliminating required water breaks for outside workers, just as the latest heat wave was due to roll in.

Meanwhile, New York’s Hudson Valley and parts of Vermont, including its capital Montpelier, were inundated this past week by a once-in-a-hundred-year storm, while in South Korea, workers raced to rescue people whose cars were trapped inside the completely submerged Cheongju tunnel after a torrential monsoon rainfall. Korea, along with much of Asia, expects such rains during the summer, but this year’s—like so many other weather statistics—have been literally off the charts. Journalists have finally experienced a sea change (not unlike the extraordinary change in surface water temperatures in the Atlantic Ocean). Gone are the tepid suggestions that climate change “may play a part” in causing extreme weather events. Reporters around the world now simply assume that’s our reality.

When it comes to confronting the climate emergency, though, the United States has once again been bringing up the rear. As far back as 1992, at the United Nations Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro, President George H.W. Bush resisted setting any caps on carbon-dioxide emissions. As The New York Timesreported then, “Showing a personal interest on the subject, he singlehandedly forced negotiators to excise from the global warming treaty any reference to deadlines for capping emissions of pollutants.” And even then, Washington was resisting the efforts of poorer countries to wring some money from us to help defray the costs of their own environmental efforts.

On July 13, climate envoy John Kerry told a congressional hearing that “under no circumstances” would the United States pay reparations to developing countries suffering the devastating effects of climate change.

Some things don’t change all that much. Although President Joe Biden reversed Donald Trump’s move to pull the U.S. out of the Paris climate accords, his own climate record has been a combination of two steps forward (the green energy transition funding found in the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act, for example) and a big step back (greenlighting the ConocoPhillips Willow oil drilling project on federal land in Alaska’s north slope, not to speak of Senator Joe Manchin’s pride and joy, the $6.6 billion Mountain Valley Pipeline for natural gas).

And when it comes to remediating the damage our emissions have done to poorer countries around the world, this country is still a day late and billions of dollars short. In fact, on July 13, climate envoy John Kerry told a congressional hearing that “under no circumstances” would the United States pay reparations to developing countries suffering the devastating effects of climate change. Although at the U.N.’s COP 27 conference in November 2022, the U.S. did (at least in principle) support the creation of a fund to help poorer countries ameliorate the effects of climate change, as Reuters reported, “the deal did not spell out who would pay into the fund or how money would be disbursed.”

Welcome to Solastalgia

Fireflies blink in a meadow.

(Photo: iStock/via Getty Images)

I learned a new word recently, solastalgia. It actually is a new word, created in 2005 by Australian philosopher Glenn Albrecht to describe “the distress that is produced by environmental change impacting on people while they are directly connected to their home environment.” Albrecht’s focus was on Australian rural Indigenous communities with centuries of attachment to their particular places, but I think the concept can be extended, at least metaphorically, to the rest of us whose lives are now being affected by the painful presences (and absences) brought on by environmental and climate change: the presence of unprecedented heat, fire, noise, and light; the presence of deadly rain and flooding; and the growing absence of ice at the Earth’s poles or on its mountains. In my own life, among other things, it’s the loss of fireflies and the almost infinite sadness of rarely seeing more than a few faint stars.

Of course, the “best country in the world” wasn’t the only nation involved in creating the horrors I’ve been describing. And the ordinary people who live in this country are not to blame for them. Still, as beneficiaries of this nation’s bounty—its beauty, its aspirations, its profoundly injured but still breathing democracy—we are, as the philosopher Iris Marion Young insisted, responsible for them. It will take organized, collective political action, but there is still time to bring our outlaw country back into what indeed should be a united community of nations confronting the looming horrors on this planet. Or so I hope and believe.