The Mainstream Media Still Won't Follow Up on the Epstein-Israel Connection

On top of the grotesque and horrifying photos and emails that appear to offer more evidence of systemic and widespread child abuse, the Epstein files revealed further allegations of his ties to Israel and its intelligence agency Mossad.

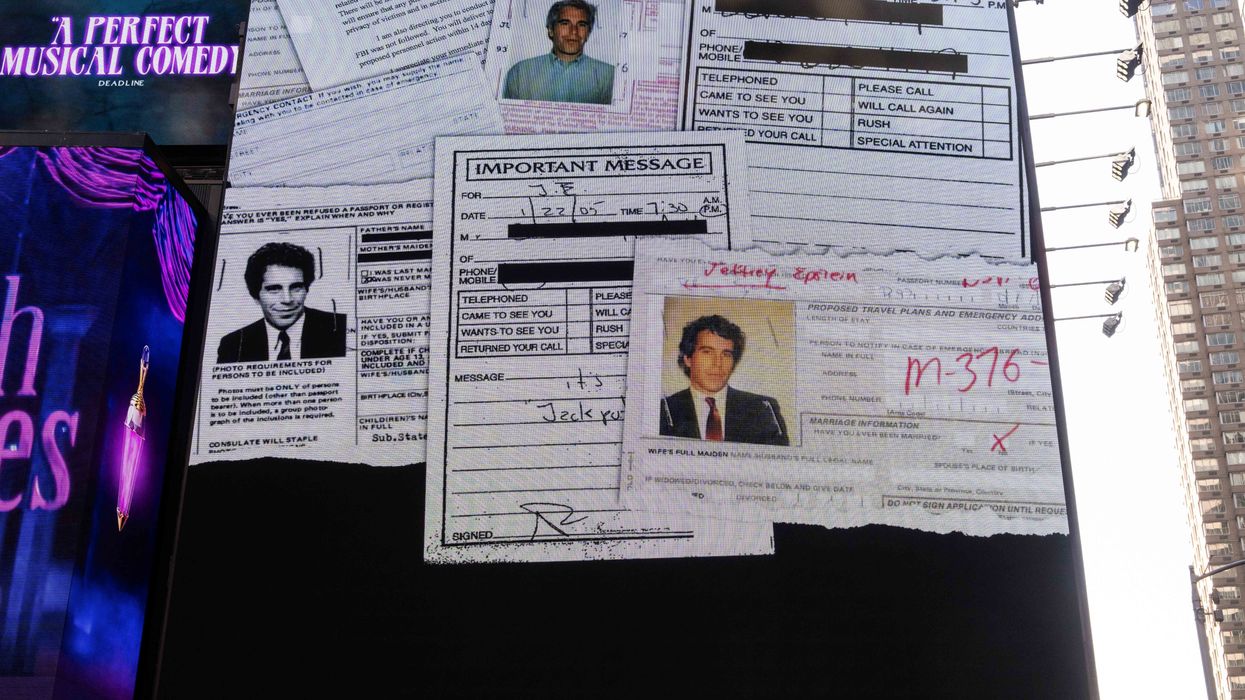

Late last month, the US Department of Justice published 3.5 million pages about convicted sex offender and financier Jeffrey Epstein.

On top of the grotesque and horrifying photos and emails that appear to offer more evidence of systemic and widespread child abuse, the Epstein files revealed further allegations of his ties to Israel and its intelligence agency Mossad.

The Epstein-Israel revelations have been covered at length by independent and overseas media outlets:

- “The Israeli government installed security equipment and controlled access to a Manhattan apartment building” that Epstein managed (Drop Site News, 2/18/26). Former Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak and Israeli spy Yoni Koren were frequent guests at the apartment, and Rafi Shlomo, then-director of protective service at the Israeli mission to the United Nations, “controlled access to the apartment for guests, and even conducted background checks on cleaners and Epstein’s employees.”

- An informant told the FBI he “became convinced that Epstein was a co-opted Mossad agent” (Middle East Monitor, 2/8/26).

- Epstein emailed Barak in December 2018: “You should make clear that I don’t work for Mossad :)” (Dissident, 2/2/26). Barak responded, “You or I?” Epstein replied, “That I don’t :).”

- Epstein emailed Barak twice in November 2017 (London Times, 2/8/26): “Did Boies ask you to help obtain former Mossad agents to do dirty investigations?” and “Boies said he got to the Mossad guys through you? True? This is getting a lot of press.” Barak responded, “Call me. [Redacted] in Paris.” (Epstein was likely referring to attorney David Boies, who was facing scrutiny at the time for hiring a private firm, run largely by former Mossad officers, to investigate women who accused his client Harvey Weinstein of rape, and journalists trying to expose the allegations—New Yorker, 11/6/17.)

- Epstein’s foundation backed pro-Israel projects like Friends of Israel Defense Forces and the Jewish National Fund, which buys land in Palestine to build settlements (Middle East Eye, 2/7/26).

Adding to Existing Evidence

It is important to note that the Epstein emails contain allegations and intimations, and don’t prove that Epstein was an Israeli agent, formally or informally. However, they do add to the existing evidence that Epstein used his considerable connections and wealth to assist the Israeli state.

The Epstein-Israel ties were reported before the latest DOJ release by various independent media outlets, particularly Drop Site News. Drop Site’s reporting received scant coverage by US corporate media, as I documented at the time (FAIR.org. 11/14/25).

Drop Site based its reporting on a hack purportedly emanating from Iran’s government. The hack’s source seemed to have explained—at least in part—the lack of US corporate media coverage. The latest Epstein-Mossad ties, on the other hand, were uncovered in a release by the DOJ—a more acceptable source by US corporate media standards. (The Justice release confirmed some of the details in Drop Site‘s reporting based on the Iranian hack, such as Epstein’s close ties to the Israeli spy Yoni Koren—Drop Site, 11/11/25; Al Jazeera, 2/9/26.)

And yet only a few US corporate media outlets—most notably Axios, New York magazine, the New York Times, Wall Street Journal and Atlantic—have referenced the latest Epstein-Israel revelations.

Even then, these outlets cast doubt on the legitimacy of the connections by framing them as conspiracy theories, or conspiracy-adjacent—hardly a surprise, given previous US corporate media coverage.

‘Ample Fodder for Speculation’

Axios (2/3/26) wrote:

FBI source reports and internal emails contain unverified claims and secondhand suspicions about Epstein’s possible ties to Mossad and other intelligence services—material that stops well short of proof, but offers ample fodder for speculation.

A week later, Axios (2/10/26) acknowledged that Barak and his wife “stayed at Epstein’s apartment multiple times from 2015 to 2019,” citing Israeli media reports. Axios‘ Rebecca Falconer wrote that Barak “has said he ‘deeply regrets’ his past relationship with Epstein, and that he never saw nor participated in any inappropriate behavior during their meetings.” Falconer added:

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu rejected conspiracy theories peddled online that his longtime political rival Barak’s “unusual close relationship” indicated that Epstein was an Israeli spy.

Although New York features writer Simon van Zuylen-Wood (2/6/26) mentioned “former Israeli prime minister Ehud Barak” as one of the “seemingly endless list of VIPs” corresponding with Epstein, it warned against looking too hard at Epstein’s ties to the Israeli state by linking an interest in the issue to antisemitism:

The horseshoe nature of the scandal makes it hard to untangle speculation about, say, Epstein’s intelligence ties from the antisemitism that is pervasive in Epstein discourse. “Yes, we are ruled by Satanic pedophiles who work for Israel,” announced the YouTuber Candace Owens, who may have been reading the same emails that prompted the left-wing commentator Cenk Uygur to post, “To my knowledge no one in legacy media has ever even discussed the possibility that Epstein was Mossad when it is all over the files.”

Right-wing conspiracy theories based in antisemitism (like Owens’) are a toxic form of discourse. But the latest batch of files—and Drop Site’s previous coverage, which Uygur has previously covered—is not hard to distinguish from antisemitism, and does more than just offer “ample fodder for speculation.”

‘Dark Workings of Cabals’

Still, pundits like the Wall Street Journal‘s Barton Swaim (2/11/26) treated questions of Epstein and Israel as necessarily conspiratorial, heaping scorn on “influencers and politicos determined to attribute all bad things to the dark workings of cabals,” and citing how “Tucker Carlson conjectured that Epstein worked with the Mossad to blackmail its enemies.”

And the Atlantic (2/7/26) wrote that, “in death, Epstein has taken on far more significance than he did in life”:

Some Americans were already primed to believe in international pedophilia rings. Bonus points if they were run by wealthy Jews—Jews who were perhaps on the Mossad payroll, as many conspiracists have insisted Epstein was.

Jacob Shamsian of Business Insider (2/14/26) asked whether “there were any truth to the rumored connections to the CIA or the Mossad,” only to hand wave away those connections by citing anonymous sources. Shamsian pointed to “four people who had access to the Justice Department’s files,” who “said there was no trace of intelligence material, which would have been the case if Epstein or Maxwell’s crimes were tied to the CIA or Mossad.”

To Compact editor Matthew Schmitz (Washington Post, 2/12/26), the “scourge of rising antisemitism in recent years has found its latest manifestation in the government’s release of millions of files about sex offender Jeffrey Epstein.” Schmitz referenced “antiestablishment voices” that “have advanced the claim that Jewish networks and interests are corrupting American society.” He lumped together “antisemites on the left and right,” linking Owens and Tucker Carlson with “progressive influencers” Ana Kasparian and Briahna Joy Gray. But Schmitz omitted any mention of Epstein and Barak’s very real relationship.

A Selective List of ‘Powerful Men’

The New York Times, for its part, largely downplayed the relationship between Epstein and Barak, and omitted key context. A Times article (2/5/26) on Epstein’s ties with tech start-ups briefly mentioned that Epstein “suggested to Ehud Barak, the former Israeli prime minister, that he speak with Mr. Thiel about an advisory role” at Palantir.

The Times quoted a Palantir spokesperson as denying “Epstein ever investing in or being a shareholder in Palantir,” and asserting that Palantir “has never had a business relationship with Ehud Barak.” They failed to mention that Palantir signed its first contract with the Israeli government a year after the Epstein-Barak conversation.

Less than a week later, the Times (2/11/26) wrote that “political score-settling has played a part in the reaction in other countries,” including in Israel, where Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has “played up disclosures of emails” between Epstein and Barak.

The Times noted in that piece that “India’s foreign ministry dismissed an email from Mr. Epstein, in which he appeared to take credit for the ingratiating approach of Prime Minister Narendra Modi during a landmark state visit to Israel in 2017.”

The paper omitted the detail that Epstein had connected Barak to Anil Ambani, an Indian billionaire close to Modi, ahead of the trip. Drop Site (1/31/26) reported that the introduction “helped accelerate the burgeoning relationship” between Israel, India, and the US.

More Tangible Ties

The sparse US corporate media coverage of the Epstein-Israel angle sharply contrasts with the extensive reporting of Epstein’s alleged ties to Russia.

Epstein visited Russia at least three times during the 2000s. He maintained a network of recruiters in Eastern Europe, including Russia and Ukraine, whom he tasked with finding “girls”—often using modeling agencies as a front to traffic them to the US or Europe. He maintained Russian bank accounts and sought investments in Russia.

Although Russia was referenced somewhat more often than Israel in the files—about 5,400 to 4,800 times—Epstein’s connections to Barak were far more tangible than his ties to Russian government figures.

Epstein tried to meet with Putin multiple times, but there is no evidence that he ever succeeded (Washington Post, 2/7/26). Epstein maintained relationships with Russian oligarchs, tech investors, and former Russian government officials, but there isn’t a Russian equivalent to Barak, with whom Epstein shared over 4,000 email messages.

Indeed, Epstein and Barak arranged to meet face-to-face more than 60 times between September 2010 to March 2019. At least seven of these meetings took place while Barak was serving as minister of Defense for Israel (Jacobin, 2/6/26).

‘Might Replace Putin’

At least one email thread even connected Epstein to an anti-Putin dissident. Politician Ilya Ponomarev sent an email in 2011 to Bill Gates’ adviser Boris Nikolic, asking how he could gain access to the World Economic Forum in Davos “to communicate what is going on, so that not only official Putin’s voice is heard.” His email came as Ponomarev was participating in mass protests against Putin and his reelection during the 2011 Russian presidential election.

Nikolic forwarded Ponomarev’s email to Epstein, writing: “We should go soon to Russia and you should meet my friend Ilya Ponomarev,” who he described as the “main organizer of the uprising against Putin.” He “might replace Putin and become a president by himself” if “he does not get killed before,” Nikolic said. He asked how Epstein could help, “not with Davos but with the other stuff in general.”

Epstein replied: “I can do end of March.”

It’s not clear from the files whether Epstein ever met with Ponomarev, but the email thread was noteworthy, showing Epstein’s willingness to meet with an anti-Putin dissident.

Yet it received only one mention in the US corporate media—from Yahoo (2/5/26), which republished an article from the Kyiv Independent (2/5/26), a Ukraine-based news outlet that receives funding from the CIA-linked National Endowment for Democracy.

Beyond including the email in the article, the Kyiv Independent didn’t bother expanding on its significance. Instead, the outlet wrote:

The documents do not prove that Epstein worked for Russian intelligence.

They do, however, reveal sustained, multi-year efforts by Epstein to embed himself in Russia’s political, financial, and diplomatic circles—efforts marked by persistence, access-seeking, and repeated attempts to present himself as useful to the Kremlin.

‘Whom Epstein Was Really Working For’

Among the US corporate media outlets to cover the Epstein-Russia connection in-depth are the New York Post, Washington Post, and New York Times.

A headline in the New York Post (2/2/26) read: “Emails Reveal New Theory About Whom Jeffrey Epstein Was Really Working For.”

The right-wing outlet relied on two anonymous sources—”people close to the Russian tyrant” and “US security officials”—and an article by the British tabloid Daily Mail (1/31/26), which based its reporting on “intelligence sources.”

In the final four paragraphs of the article, the New York Post acknowledged Epstein’s well-established connections to Israel—noting that his co-conspirator Ghislaine Maxwell was the daughter of British media tycoon Robert Maxwell, widely reported to be a Mossad agent—but excluded any mention of the recent revelations.

Two days later, the New York Post ran an article (2/4/26) that detailed how Poland was launching a probe into whether Epstein was working as a Russian spy.

The right-wing outlet also published an article (2/7/26) about Epstein’s ties to “key Russian government figures.” These figures included Sergey Belyakov, who the Post described as “Russia’s deputy economic minister at the time, and a Kremlin secret service-trained spy who Epstein often appeared to use as his personal fixer in Moscow,” as well as Vitaly Churkin, “Russia’s ambassador to the United Nations, between 2015 and his 2017 death.” The New York Post did not mention that Epstein introduced Belyakov to Barak in April 2015 (Reason, 8/27/25; Drop Site, 10/30/25; Washington Post, 2/7/26).

‘Added Momentum to Previous Suspicions’

The Washington Post (2/7/26) similarly hyped up a Russia connection under the headline “Epstein Built Ties to Russians and Sought to Meet Putin, Files Show.”

Jeff Bezos’ Post—which recently largely gutted its foreign reporting desk—wrote that the files “show repeated attempts in the 2010s to arrange a meeting” with Putin, but added that there was “no evidence in the Justice Department files that such a meeting ever took place.”

The Post (2/6/26) ran another article about the Russia ties, this time about “Russian expatriate tech investors who have drawn scrutiny from US intelligence agencies over their past ties with the Kremlin.”

The Post speculated:

The newly revealed extent of Epstein’s Russian connections, which also include senior Russian government officials, has added momentum to previous suspicions that he worked with or was targeted by intelligence agencies because of his personal connections to international elites.

In its own long-form article on the Epstein-Russia connection, the New York Times (2/10/26) similarly wrote that the latest batch of files have “raised new questions among Russia’s critics about whether the relationships opened the door to Russian intelligence activity.”

It is possible that Epstein was a Russian intelligence asset. However, there is no good reason for the US corporate media to frame these allegations as a real possibility, while ignoring the Epstein-Israel ties, or continuing to paint them as a far-fetched conspiracy theory.

The latest batch of files deepens the evidence, documented by Drop Site and others, that Epstein was engaged in assisting the Israeli state, serving as a go-between on commercial, diplomatic, and intelligence matters. Although Epstein maintained relationships with Russian oligarchs, tech investors, and former Russian government officials, no evidence has yet surfaced that he advocated on behalf of Russian interests. The only reasons to think that the former is more newsworthy than the latter are purely political.