How to Deal With the National Debt Without Slashing Services or Triggering Inflation

The debt has grown so massive that just the interest on it is crowding out expenditures on the public goods that are the primary purpose of government. Luckily, there are many creative solutions.

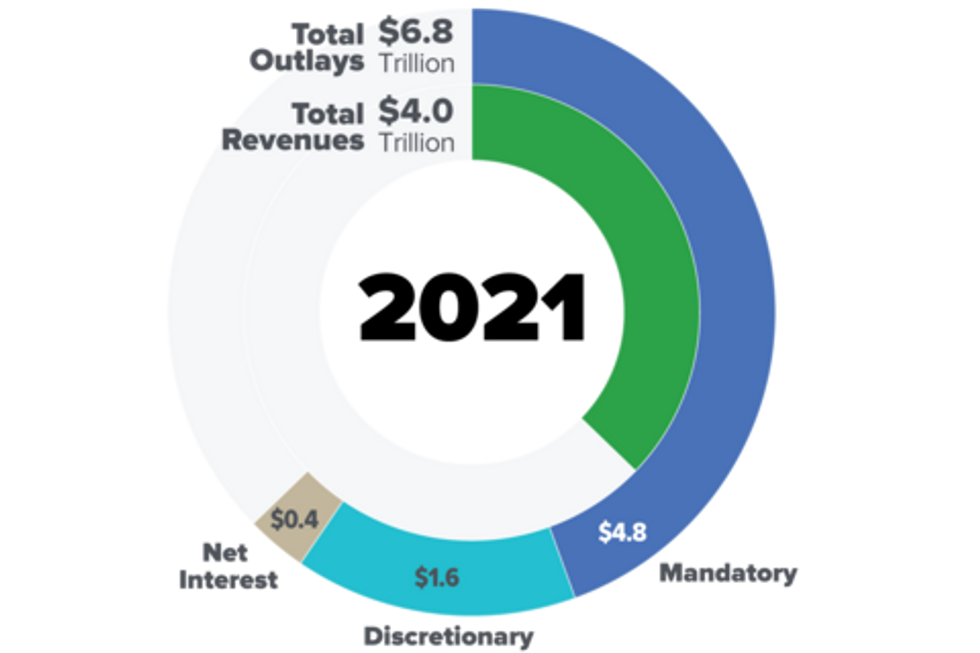

The U.S. national debt just passed $36 trillion, only four months after it passed $35 trillion and up $2 trillion for the year. Third quarter data is not yet available, but interest payments as a percent of tax receipts rose to 37.8% in the third quarter of 2024, the highest since 1996. That means interest is eating up over one-third of our tax revenues.

Total interest for the fiscal year hit $1.16 trillion, topping $1 trillion for the first time ever. That breaks down to $3 billion per day. For comparative purposes, an estimated $11 billion, or less than four days’ federal interest, would pay the median rent for all the homeless people in America for a year. The damage from Hurricane Helene in North Carolina alone is estimated at $53.6 billion, for which the state is expected to receive only $13.6 billion in federal support. The $40 billion funding gap is a sum we pay in less than two weeks in interest on the federal debt.

The current debt trajectory is clearly unsustainable, but what can be done about it? Raising taxes and trimming the budget can slow future growth of the debt, but they are unable to fix the underlying problem—a debt grown so massive that just the interest on it is crowding out expenditures on the public goods that are the primary purpose of government.

Borrowing Is Actually More Inflationary Than Printing

Several financial commentators have suggested that we would be better off if the Treasury issued the money for the budget outright, debt-free. Martin Armstrong, an economic forecaster with a background in computer science and commodities trading, contends that if we had just done that in the first place, the national debt would be only 40% of what it is today. In fact, he argues, debt today is the same as money, except that it comes with interest. Federal securities can be posted in the repo market as collateral for an equivalent in loans, and the collateral can be “rehypothecated” (re-used) several times over, creating new money that augments the money supply just as would happen if it were issued directly.

Chris Martenson, another economic researcher and trend forecaster, asked in a November 21 podcast, “What great harm would happen if the Treasury just issued its own money directly and didn’t borrow it?… You’re still overspending, you still probably have inflation, but now you’re not paying interest on it.”

The argument for borrowing rather than printing is that the government is borrowing existing money, so it will not expand the money supply. That was true when money consisted of gold and silver coins, but it is not true today. In fact borrowing the money is now more inflationary, increasing the money supply more, than if it were just issued directly, due to the way the government borrows. It issues securities (bills, bonds, and notes) that are bid on at auction by selected “primary dealers” (mostly very large banks). Quoting from Investopedia:

Because most modern economies rely on fractional reserve banking, when primary dealers purchase government debt in the form of Treasury securities, they are able to increase their reserves and expand the money supply by lending it out. This is known as the money multiplier effect.

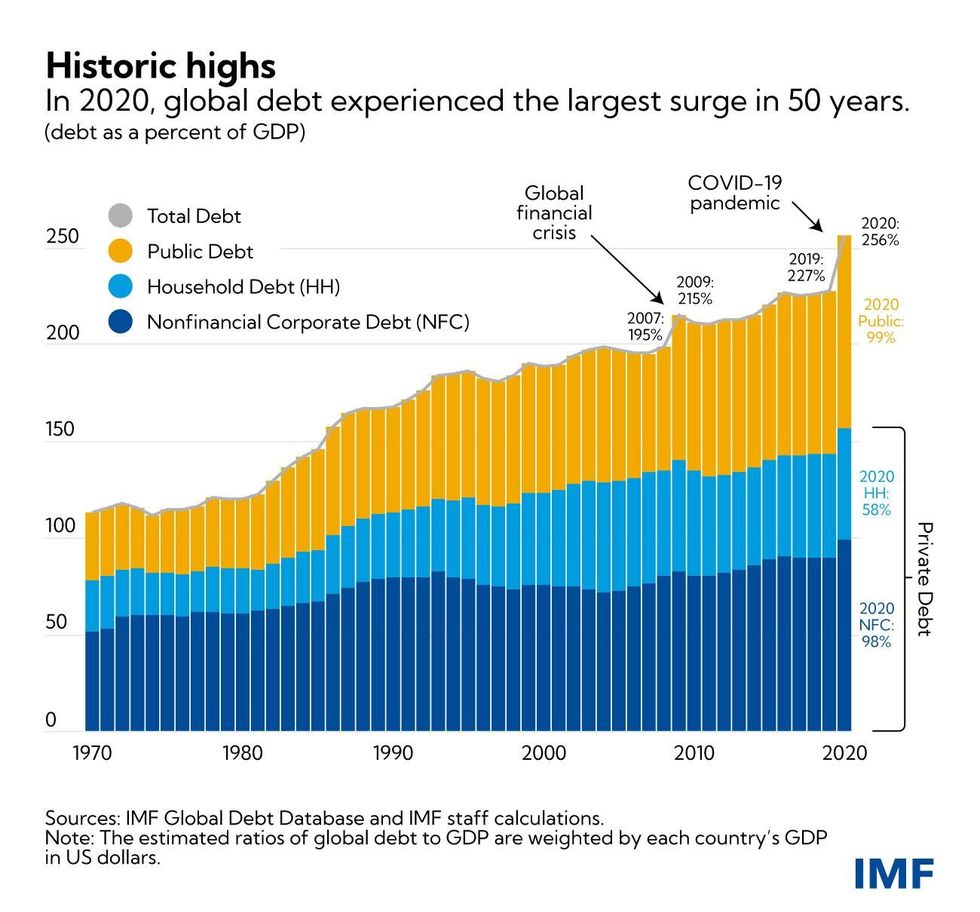

Thus, “the government increases cash reserves in the banking system,” and “the increase in reserves raises the money supply in the economy.” Principal and interest on the securities are paid when due, but they are paid with borrowed money. In effect, the debt is never repaid but just gets rolled over from year to year along with the interest due on it. The interest compounds, an increasing amount of debt-at-interest is generated, and the money supply and inflation go up.

U.S. Currency Should Be Issued by the U.S. Government

Well over 90% of the U.S. money supply today is issued not by the government but by private banks when they make loans. As Thomas Edison argued in 1921, “It is absurd to say that our country can issue $30 million in bonds and not $30 million in currency. Both are promises to pay, but one promise fattens the usurers and the other helps the people.”

The government could avoid increasing the debt by printing the money for its budget as President Abraham Lincoln did, as U.S. Notes or “Greenbacks.” Donald Trump acknowledged in 2016 that the government never has to default “because you print the money,” echoing Alan Greenspan, Warren Buffett, and others. So writes Prof. Stephanie Kelton in a Dec. 2, 2024 blog. Alternatively, the Treasury could mint some trillion dollar coins. The Constitution gives Congress the power to coin money and regulate its value, and no limit is put on the value of the coins it creates. In legislation initiated in 1982, Congress chose to impose limits on the amounts and denominations of most coins, but a special provision allowed the platinum coin to be minted in any amount for commemorative purposes. Philip Diehl, former head of the U.S. Mint and co-author of the platinum coin law, confirmed that the coin would be legal tender:

In minting the $1 trillion platinum coin, the Treasury Secretary would be exercising authority which Congress has granted routinely for more than 220 years… under power expressly granted to Congress in the Constitution (Article 1, Section 8).

To prevent congressional overspending, a budget ceiling could be imposed— as it is now, although the terms would probably need to be revised.

Eliminating the Debt

Those maneuvers would prevent the federal debt from growing, but it still would not eliminate the trillion-dollar interest tab on the existing $36 trillion debt. The only permanent solution is to eliminate the debt itself. In ancient Mesopotamia, when the king was the creditor, this was done with periodic debt jubilees—just cancel the debt. (See Michael Hudson, And Forgive Them Their Debts.) But that is not possible today because the creditors are private banks and private investors who have a contractual right to be paid, and the U.S. Constitution requires that the government pay its debts as and when due.

Another possibility is a financial transaction tax, which could replace both income and sales taxes while still generating enough to fund the government and pay off the debt. See Scott Smith, A Tale of Two Economies: A New Financial Operating System for the American Economy (2023) and my earlier article here. But that solution has been discussed for years without gaining traction in Congress.

Another alternative is to have the Federal Reserve buy the debt as it comes due. For the last few years, the Treasury has been issuing an estimated 30% of its debt as short-term bills rather than 10-year or 30-year bonds. As a result, in 2023 approximately 31% of the outstanding debt came due for renewal. As usual, it was just rolled over into new debt. But the nearly one-third coming due in FY2025 could be bought in the open market by the Federal Reserve, which is required to return its profits to the government after deducting its costs, making the debt virtually interest-free. Interest-free debt carried on the books and rolled over does not raise the federal deficit. If a third of the outstanding debt is too much to monetize in one year to avoid inflation, this maneuver could be spread out over a number of years.

Mandating that action by an “independent” Fed would require an amendment to the Federal Reserve Act, but Congress has the power to amend it and has done so several times over the years. The incoming administration is proposing more radical moves than that, including eliminating the income tax, ending the Fed, auditing the Fed, or merging it with the Treasury. The federal interest tab nearly doubled after April 2022, when the Fed initiated “Quantitative Tightening.” It reduced its balance sheet by selling over $2 trillion in federal securities into the economy, reducing the money supply, and by hiking the federal funds rate to as high as 5.5%. Arguably the Fed has overtightened and needs to reverse that trend by buying federal securities, injecting new money into the economy.

Alarmed economists contend that a Weimar-style hyperinflation is the inevitable outcome of government-issued money. But as Michael Hudson points out, “Every hyperinflation in history has been caused by foreign debt service collapsing the exchange rate. The problem almost always has resulted from wartime foreign currency strains, not domestic spending.”

Issuing the money directly will not inflate prices if the funds are used to increase the domestic supply of goods and services. Supply and demand will then go up together, keeping prices stable. This has been illustrated historically, perhaps most dramatically in China. The People’s Bank of China manages the money supply by a variety of means including just printing currency. In 28 years, from 1996 to 2024, China’s money supply (M2) grew by 52 times or 5,200%, yet hyperinflation did not result. Prices remained stable because the funds went into increasing GDP, which went up along with the money supply.

Price inflation during the Covid-19 crisis has been blamed on the Fed monetizing congressional fiscal payments to consumers and businesses, increasing demand (the circulating money supply) without increasing supply (goods and services). But the San Francisco Fed concluded that the surge in global shipping and transportation costs due to Covid-19 along with delivery delays and backlogs, were a greater contributor than this fiscal stimulus to the run-up of headline inflation in 2021 and 2022. The supply of goods could have been increased—producers could have increased production to respond to the increase in demand—were it not for the shutdown of more than 700,000 productive businesses labeled “non-essential,” resulting in the loss of 3 million jobs.

Swapping Debt for Productive Equity

Money printing is not inflationary if the money is issued for productive purposes, raising GDP in lockstep; but how can we be sure that the new money will be used productively? Today the banks and other large institutions that first receive any newly-issued money are more likely to invest it speculatively, driving up the price of existing assets (homes, stocks, etc.) without creating new goods and services.

Economic blogger Martin Armstrong observes that one solution pursued by debt-ridden countries is to swap the debt for equity in productive assets. This has been done by Mexico, Poland, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Hungary, and the United States itself. It was the solution of Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton in dealing with the overwhelming debt of the First U.S. Congress. State and federal debt was swapped along with gold for shares in the First U.S. Bank, paying a 6% dividend. The Bank then issued U.S. currency at up to 10 times this capital base, on the fractional reserve model still used by banks today. Both the First and the Second U.S. Banks were designed to support manufacturing and production, according to Hamilton’s Report on Public Credit.

Following the Hamiltonian model is H.R. 4052, the National Infrastructure Bank Act of 2023 (NIB) now pending in Congress. The NIB proposal is to swap privately-held federal securities (Treasury bonds) for non-voting preferred stock in the bank. Interest on the bonds would continue to go to the investors, along with a 2% stock dividend. That would not eliminate the debt or the interest, but if the Federal Reserve were to buy federal securities on the open market and swap them for NIB stock, the securities would essentially remain interest-free, since again the Fed is required to return its profits to the Treasury after deducting its costs.

Lending Directly to Productive Businesses

Another possibility for using newly issued money to increase the supply of goods and services is for the Federal Reserve to make loans directly to productive businesses. That was actually the intent of the original Federal Reserve Act. Section 13 of the Act allows Federal Reserve Banks to discount notes, drafts, and bills of exchange arising out of actual commercial transactions, such as those issued for agricultural, industrial, or commercial purposes—in other words, lending directly for production and development. “Discounting commercial paper” is a process by which short-term loans are provided to financial institutions using commercial paper as collateral. (Commercial paper is unsecured short-term debt, usually issued at a discount, used to cover payroll, inventory, and other short-term liabilities. The “discount” represents the interest to the lender.) According to Prof. Carl Walsh, writing of the Federal Reserve Act in The Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Newsletter in 1991:

The preamble sets out very clearly that one purpose of the Federal Reserve Act was to afford a means of discounting commercial loans. In its report on the proposed bill, the House Banking and Currency Committee viewed a fundamental objective of the bill to be the “creation of a joint mechanism for the extension of credit to banks which possess sound assets and which desire to liquidate them for the purpose of meeting legitimate commercial, agricultural, and industrial demands on the part of their clientele.”

Cornell Law School Professor Robert Hockett expanded on this design in an article in Forbes in March 2021:

[T]he founders of the Federal Reserve System in 1913… designed something akin to a network of regional development finance institutions… Each of the 12 regional Federal Reserve Banks was to provide short-term funding directly or indirectly (through local banks) to developing businesses that needed it. This they did by ‘discounting’—in effect, purchasing—commercial paper from those businesses that needed it… [I]n determining what kinds of commercial paper to discount, the Federal Reserve Act both was—and ironically remains—quite explicit about this: Fed discount lending is solely for “productive,” not “speculative” purposes.

Today discounting commercial paper is big business, but the lenders are private and the borrowers are large institutions issuing commercial paper in denominations of $100,000 or more. Except for its emergency Commercial Paper Funding Facility operated from 2020 to 2021 and from 2008 to 2010, the Fed no longer engages in the commercial loan business. Meanwhile, small businesses are having trouble finding affordable financing.

In a sequel to his March 2021 article, Hockett explained that the drafters of the Federal Reserve Act, notably Carter Glass and Paul Warburg, were essentially following the Real Bills Doctrine (RBD). Previously known as the “commercial loan theory of banking,” it held that banks could create credit-money deposits on their balance sheets without triggering inflation if the money were issued against loans backed by commercial paper. When the borrowing companies repaid their loans from their sales receipts, the newly created money would just void out the debt and be extinguished. Their intent was that banks could sell their commercial loans at a discount at the Fed’s Discount Window, freeing up their balance sheets for more loans. Hockett wrote:

The RBD in its crude formulation held that so long as the lending of endogenous [bank-created] credit-money was kept productive, not speculative, inflation and deflation would be not only less likely, but effectively impossible. And the experience of German banks during Germany’s late 19th century Hamiltonian ‘growth miracle,’ with which the German immigrant Warburg, himself a banker, was intimately familiar, appeared to verify this. So did Glass’ experience with agricultural lending in the American South.

Prof. Hockett suggested regionalizing the Fed, expanding it from the current 12 Federal Reserve banks to many banks. He wrote in August 2021:

In time, we might even imagine a proliferation of public banks, patterned more or less after the highly successful Bank of North Dakota model, spreading across multiple states. These banks could then both afford nonprofit banking services to all, and assist the Fed Regional Banks in identifying appropriate recipients of Fed liquidity assistance.

The result, he said, will be “a Fed restored to its original purpose, a Fed responsive to varying local conditions in a sprawling continental republic, a Fed no longer over-involved with banks whose principal if not sole activities are in gambling on price movements in secondary and tertiary markets rather than investing in the primary markets that constitute our ‘real’ economy. It will mean, in short, something approaching a true people’s bank, not just a banks’ bank.”