We also know that Mountbatten-Windsor was the UK’s trade envoy between 2001 and 2011, and appears to have forwarded to Epstein confidential government reports from visits to Vietnam, Singapore, and China, including investment opportunities in gold and uranium in Afghanistan.

Prime Minister Keir Starmer says, “No one is above the law.” The family of Virginia Giuffre says, “No one is above the law, not even royalty.” Britain’s chief prosecutor says, “No one is above the law.”

Instead of bureaucracies, America now has a royal entourage. Instead of institutions, we now have royal prerogative.

All of which raises awkward questions about the people implicated on this side of the pond, including the person in the Oval Office who loves to be treated like a king, and who appears in the Epstein files 1,433 times (that is, the files that have been released so far). Prince Andrew appears in them 1,821 times.

America likes to believe we gave up kings almost 250 years ago and adopted a system in which “no one is above the law.”

But President Donald Trump’s foreign policy has become a personal tool for him to channel money and status to himself and his closest associates. Since the 2024 election, the Trump family’s personal wealth has increased by at least $4 billion.

As with the British royalty of the 16th century, it’s all personal with Trump—all about expanding his power and enlarging his and his family’s wealth. Proceeds from the sale of Venezuelan oil? “That money will be controlled by me,” he says. The gift of a plane from Qatar? “Mine.” Investments by Middle-East kingdoms in his family’s crypto racket? “Perfectly fine.”

Like the British royalty of yore, King Trump has arbitrary power. He raises Switzerland’s tariff from 30-39% because its former president Karin Keller-Sutter “just rubbed me the wrong way.” He imposes a 50% tariff on Brazil because Brazil refused to halt its prosecution of Trump’s political ally, the former Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, who was found guilty of plotting a coup. Vietnam fast-tracks approval of a $1.5 billion Trump family golf course at the same time it seeks to reduce its tariff rate.

Trump claims that Greenland is “psychologically needed,” although the United States already has a military presence there and an open invitation to expand its bases. He muses about making Canada the “51st state.” These are throwbacks to the 16th-century age of empire.

***

Meanwhile, Trump has created a system of tribute and allegiance that would make Henry VIII jealous.

Apple’s Tim Cook delivers a gold-based plaque and a donation to Trump’s planned ballroom. Swiss billionaires bring a gold bar and a Rolex desk clock to the Oval Office. Jeff Bezos backs a vapid movie of Melania and hands her a check for $28 million.

Trump pardons Changpeng Zhao, the billionaire mogul who pled guilty to money-laundering violations in 2023, after which time Zhao’s Binance digital-coin trading platform becomes the engine of the Trump family’s crypto business, World Liberty Financial.

King Trump was evidently involved in Jeffrey Epstein’s nefarious doings. We don’t know exactly how because there’s been no criminal investigation. But shouldn’t there be?

Elon Musk’s humongous quarter-billion-dollar contribution to Trump’s 2024 campaign earns Musk a dukedom—a “department of government efficiency”—and the keys to the kingdom in the form of sensitive US Treasury Department software systems used to manage federal payments.

But when the Duke of DOGE starts becoming more visible than King Trump, the king banishes him and revokes his dukedom. When the banished Musk begins openly criticizing Trump, the king threatens to cut off Musk’s head in the form of cutting him and his SpaceX off from valuable government contracts. This puts an end to Musk’s impertinence.

The new TikTok (on which Trump has more than 16 million followers) will continue operating in the United States—but now with the financial backing of Trump ally Larry Ellison’s Oracle;Trump’s allied Emirati investment firm MGX (which has already invested in the Trump family’s cryptocurrency company); and Silver Lake, teamed up with the private equity firm founded by Trump’s son-in-law Jared Kushner.

Trump allows Nvidia to sell chips to the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia and extends military guarantees to Qatar—all of which have invested in the Trump family empire. (Emirati-backed investors plowed $2 billion into World Liberty Financial.)

Instead of national glory, Trump demands personal glory—to get the Nobel Peace Prize, to put his name on the Kennedy Center and Penn Station, and other major monuments and buildings.

If his commands are not met, he punishes. Because Norway didn’t give him a Nobel (it wasn’t Norway’s to give anyway), he “no longer feels obliged to think only of peace.” Because performers refuse to appear at the “Trump-Kennedy” Center, he shutters it.

Instead of bureaucracies, America now has a royal entourage. Instead of institutions, we now have royal prerogative. Instead of legitimacy based on the will of the people, there’s divine right (“I had God on my side,” “God was protecting me,” “God is on our side”).

***

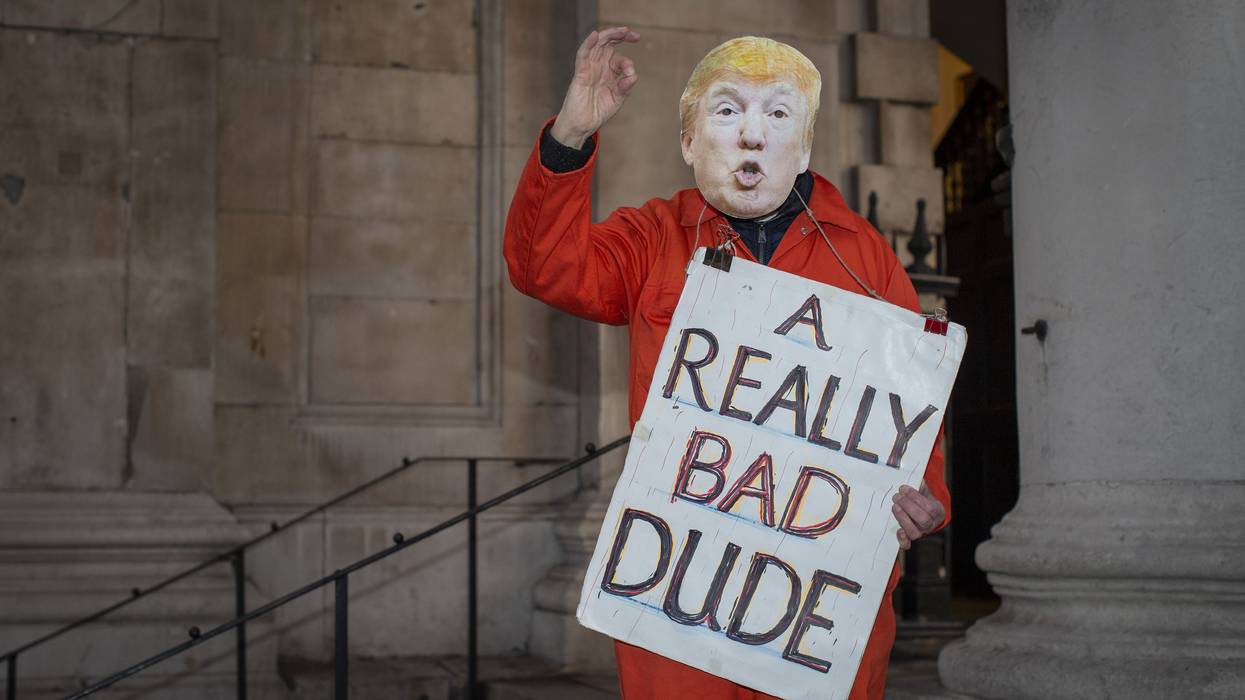

We will march against King Trump on the next “No Kings Day” on March 28—hopefully making it the biggest protest in American history.

But the arrest of the former Prince Andrew raises an issue that goes way beyond protesting and marching. King Trump was evidently involved in Jeffrey Epstein’s nefarious doings. We don’t know exactly how because there’s been no criminal investigation. But shouldn’t there be?

Pam Bondi obviously won’t investigate Trump because she’s part of King Trump’s court. But what about a group of state attorneys general?

Trump has also been enriching himself and his family through his public office, violating multiple laws about conflicts of interest.

If the UK can arrest the former Prince Andrew on evidence of such wrongdoing, why shouldn’t America arrest King Trump? If no one is above the law in the UK, not even royalty, presumably no one is above the law in the US, not even a president.

Pam Bondi obviously won’t investigate Trump because she’s part of King Trump’s court. But what about a group of state attorneys general?

Almost 250 years after we broke with George III, the question must now be faced: Are we a monarchy or a nation of laws?