SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

The rich world—represented mostly by the US, though with parts of Europe and Canada playing supporting roles—has decided that if anyone’s going to deal with climate change it’s not going to be us.

In a rational world, it would have made sense for the rich countries to take the lead in fighting climate change. After all, it was rich countries got that way precisely by burning fossil fuel in the two centuries since the Industrial Revolution, and it’s the Global South that is paying most of the price in terms of drought, flood, and fire.

That’s why, since the international climate negotiations began 30 years ago, the assumption has been that the Global North should lead the way—we had “common but differentiated responsibilities” for the future, and the job of the north was to help finance the transition away from dirty energy.

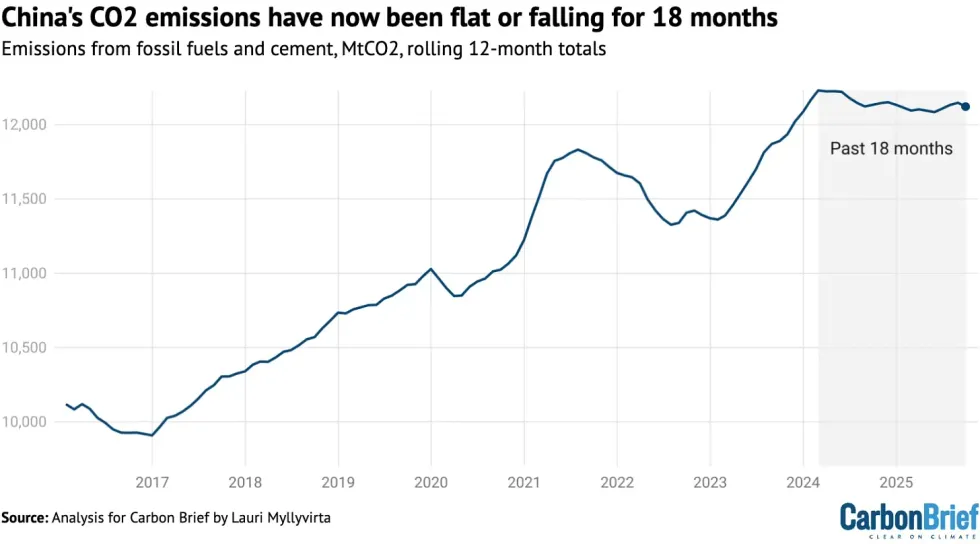

But as this year’s round of global climate talks get underway in Belém, it’s becoming clear that this commonsensical (and moral) understanding of the situation has been essentially turned on its head. If there’s going to be a solution, for now it’s mostly going to come from the poorer nations of the world. The chart above shows China—it’s emissions of carbon dioxide have apparently now peaked, or at least plateaued. It should come as no great wonder to readers of this newsletter why: Their barely believable expansion of clean carbon-free energy has been the most important technological story since… the Industrial Revolution. And it shows no signs of stopping. Here, for example, is a picture of a new offshore wind turbine that the Chinese are testing.

You might notice that it has two heads instead of one. As You Ziaojing reports in Scientific American:

With a capacity of 50 MW, this supersized structure is designed to float on the ocean’s surface and can withstand typhoons, according to the company, which plans to start making the turbine later this year and to deploy it next year.

Han Yujia, a researcher of renewable energy at the California-based nonprofit Global Energy Monitor, is most impressed that Ming Yang intends to increase a turbine’s capacity by more than 20 MW in one go, far outpacing the industry’s average rate of increase of 2-3 MW each year.

If you want to read more about the spectacular events in China, the Economist has a special issue on the subject—the key articles are here, here, and here, and just to give you a sense of what’s happening there:

The scale of the renewables revolution in China is almost too vast for the human mind to grasp. By the end of last year, the country had installed 887 gigawatts of solar-power capacity—close to double Europe’s and America’s combined total. The 22m tonnes of steel used to build new wind turbines and solar panels in 2024 would have been enough to build a Golden Gate Bridge on every working day of every week that year. China generated 1,826 terawatt-hours of wind and solar electricity in 2024, five times more than the energy contained in all 600 of its nuclear weapons.

In the context of the cold war, the distinctive measure of a “superpower” was the combination of a continental span and a world-threatening nuclear arsenal. The coming-together of China’s enormous manufacturing capacity and its ravenous appetite for copious, cheap, domestically produced electricity deserves to be seen in a similar world-changing light. They have made China a new type of superpower: One which deploys clean electricity on a planetary scale.

But this miracle is verging on "old news—I’ve been telling the tale since my book came out earlier this year, always to somewhat amazed audiences.

The next half of the story is what’s unfolding around the rest of the developing world, as countries increasingly look to China, not the US, for leadership. Here’s what André Corrěa de Lago, the Brazilian diplomat chairing the COP30 conference, told reporters earlier this week:

“China is coming up with solutions that are for everyone, not just China,” he said. “Solar panels are cheaper, they’re so competitive [compared with fossil fuel energy] that they are everywhere now. If you’re thinking of climate change, this is good.”

You can see this showing up in many ways around the world. In Pakistan, for instance:

Between 2022 and 2024 trade statistics show Pakistan’s annual imports of Chinese-made solar panels increasing almost fivefold to 16 gigawatts. In the first nine months of 2025 it imported another 16GW. By the end of this year, its cumulative solar imports are expected roughly to match the installed generation capacity of the national power system—capacity augmented quite recently by four spanking new coal-fired plants built and financed by China as part of its global Belt and Road infrastructure scheme.

Since 2022 the power providers responsible for that legacy capacity have seen their revenues plummet. Power consumption from the grid has dropped by around 12%. With new solar users increasingly likely to install Chinese-made batteries that allow them to enjoy access to electricity after sunset, that fall looks likely to continue.

Never to be outdone by Pakistan, word comes from India that giant conglomerate Tata—biggest provider of everything from defense equipment to tea—is now building the country’s biggest factory for making the polysilicon ingots that are the foundation of solar cells. As N.R. Sethuraman reports:

Some Indian companies have shifted focus to producing cells as well as ingots and wafers, as higher US tariffs on Indian products have made solar module exports less attractive.

“We find that there’s already adequate capacity of modules and many cell plants are under construction in India,” Sinha said on a post-earnings call, justifying his firm’s plan to set up a wafers and ingots factory.

So far, Adani Group has set up a plant to produce 2 GW of ingots and wafers annually.

Tata Power’s plans align with the Indian federal government’s push for increased use of locally made ingots and wafers for solar panel manufacturing to cut reliance on imports from China towards the end of the decade.

But it’s not just at the high end of the business world. Consider Yamuna Mathewsaran’s report on how Jordanian mechanics are building a big business out of recycling EV batteries to backup home solar systems:

EV batteries that are classed as end-of-life may still retain up to 80% of their original capacity, according to the International Energy Agency, which means they can still be used in second-life applications, such as household energy storage.

“I’ve seen and heard of spent batteries being hooked up to solar systems or other local power setups, often at family farms or vacation homes in semi-remote areas,” said Fadwa Dababneh, C-Hub’s director.

As well as saving money on bills and reducing battery waste, using spent batteries for energy storage stabilises the electricity grid as Jordan aims to get half of its power from renewables by 2030, up from 29% today.

This, of course, is in dire contrast to the abdication of responsibility underway in the West, especially in the US. I’m not going to go into more bloody detail than is necessary, but:

At COP26 in Glasgow in 2021, the UK, the US, the EU and other countries forged the global methane pledge, requiring a cut in methane of 30% by 2030. About 159 countries subsequently signed up.

Yet emissions from some of the main signatories have increased, data from the satellite analysis company Kayrros shows, which is likely to further raise global temperatures. Collectively, emissions from six of the biggest signatories—the US, Australia, Kuwait, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Iraq—are now 8.5% above the 2020 level.

Kuwait and Australia have made progress on cutting their emissions but emissions from US oil and gas operations have increased by 18%.

Again, this is disgusting, and it will get worse. Under fracking exec energy secretary Christopher Wright, America is rolling back its modest methane reporting requirements

US consumers—who Mr Trump promised lower bills—will end up paying more because he also made renewable energy more expensive.

And that’s to say nothing of the impact on carbon emissions.

This “greenlash” has extended to other parts of the Western world—as the always sage activist and analyst Luisa Neubauer writes from Germany:

When searching for explanations for the paradoxical decrease in governments’ efforts at a time when climate threats are dramatically increasing, many land on three forces: public fatigue, financial constraints, and geopolitical instability. All three are real.

But none, as she points out, are good reasons for slowing down, and indeed:

Decarbonising economies that have throughout their existence depended on fossil fuels is complicated, and will only become more so. But there is no more important task for governments than finding ways through these challenges and forging alliances of the willing to protect life. If common politics doesn’t grow a spine, then public commentators must—for the sake of, well, everything.

In fact, a new report from the think tank Ember makes clear that Europe will benefit immensely from quick electrification. And indeed, there are signs that Europe will still push ahead. They’re coming, interestingly, from the central European countries long considered the continent’s coal belt. As Gavin Maguire writes:

Power systems across Central Europe—hardly known for its sunny skies—are emerging as surprise leaders in global energy transition efforts through canny use of solar parks and locally-made battery energy storage systems.

Several major Central European economies—including Austria, Hungary, Romania, and Poland—have sharply boosted the share of utility electricity production from solar farms since 2022 as part of efforts to boost home-grown energy supplies.

Between 2022 and 2025 there has been a 472% rise in battery energy storage capacity within Austria, Hungary, and Romania alone, according to local utility filings.

Even in America there are signs of life. Some of these are built on sheer momentum: Texas, for instance, just signed up two huge new solar farms, which together will deliver a gigawatt of power. But there are also signs of spirited resistance. California Gov. Gavin Newsom went to Belém representing the world’s fourth largest economy, and he said Trump was “doubling down on stupid” when it came to climate. Illinois Gov. JB Pritzker keeps winning high marks for his climate policy too, and shows no sign of slowing down.

But as Wen Stephenson points out in a new essay in The Nation, overall it’s been the worst year ever for American climate politics, with many theoretically environmentally conscious politicians retreating under the cover provided by the likes of Bill Gates. In Stephenson’s Massachusetts, for example, despite the noble leadership of Boston Mayor Michelle Wu and Sen. Ed Markey, and the behind-the-scenes steadfastness of Gov. Maura Healey’s crack climate team, the state legislature is considering cutting and running. Rep. Mark Cusack is pushing hard for a bill to weaken the state’s climate goals, in essence arguing that Trump is making it too hard. In essence, the state’s plan to cut emissions in half would become “advisory and unenforceable.” Meanwhile, in New York, the increasingly egregious Gov. Kathy Hochul (named to Time’s Climate 100 list despite an almost year-long blockage of congestion pricing laws) has not only come out for a new gas pipeline backed by Trump, but also, to use the headline supplied by Politico, “approved a permit for a gas-fired cryptocurrency miner.” Now there’s leadership for the ages!

What it all adds up to is that the rich world—represented mostly by the US, though with parts of Europe and Canada playing supporting roles—has decided that if anyone’s going to deal with climate change it’s not going to be us. We got so rich burning fossil fuels that any sacrifice—or any change at all, since at this point sun and wind are the cheapest forms of power we know—seems like an impossible affront. Some of us will keep working hard to change that immorality, but in the meantime it’s apparently up to the poorest people on Earth to deal with the problems we caused. As Somini Sengupta and Brad Plumer report from Belém:

Countries like Brazil, India, and Vietnam are rapidly expanding solar and wind power. Poorer countries like Ethiopia and Nepal are leapfrogging over gasoline-burning cars to battery-powered ones. Nigeria, a petrostate, plans to build its first solar-panel manufacturing plant. Morocco is creating a battery hub to supply European automakers. Santiago, the capital of Chile, has electrified more than half of its bus fleet in recent years.

Nothing fair about it, but the only consolation for those countries is that they’re building low-cost energy economies that before long will outcompete lazy and complacent America.

The record in Mozambique shows that projects backed by public finance can harm communities and the environment unless local voices guide the process.

The ninth Tokyo International Conference on African Development, or TICAD, opened August 20 in Yokohama, organized by the Japanese government with the United Nations, UN Development Program, World Bank, and African Union Commission. Japan, as host, aims to promote “high quality” development in Africa by applying lessons from Asia. Three decades since TICAD’s launch in 1993, interest in Africa remains strong—and so does the need to reflect on what “development” truly means.

Japan’s record in Mozambique offers sobering lessons.

Before we can discuss “development” we must recognize that many of Africa’s deep crises today are rooted in the continued exploitation of its people and resources, shaped by inherited colonial structures. Public funding and transnational corporations play a large role in perpetuating these patterns.

The Mozambique liquefied natural gas (LNG) project illustrates the problem. Led by French energy giant TotalEnergies, it is one of Africa’s largest gas extraction projects, with Japan as its top financier. The publicly funded Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC) has committed up to $3.5 billion in loans, while Nippon Export and Investment Insurance (NEXI) has agreed to provide $2 billion in insurance.

As leaders gather at TICAD to shape Africa’s future, we urge Japan and all participating governments and businesses to focus on the needs and aspirations of African people themselves.

JBIC justifies this support by citing growing global LNG demand, particularly in developing countries, rising environmental awareness, and Japan’s energy security. Yet revenue flows to a United Arab Emirates-based special purpose entity—enabling gas and mining companies to avoid paying an estimated $717 million to $1.48 billion in taxes to Mozambique. The country is further disadvantaged by the Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) system, which prioritizes loss compensation for investors.

On the ground, grievances remain unresolved. More than eight communities have been affected, and many families still await promised compensation. Others have lost farmland or access to the sea, undermining agriculture and fisheries livelihoods. Local residents report that consultation meetings often involve military presence, stifling open discussion.

Since 2017, the region has suffered violent insurgency, which halted the project in 2021 and brought heavy militarization focused on protecting gas infrastructure. Insurgent activity has surged again in recent weeks, amid signs of project restart. In March 2025, analysts warned that the sense of disenfranchisement created by the project could fuel insurgent recruitment.

Environmental and climate risks are also high. Independent reviews find that the project’s environmental impact assessment understates potential harm, including lacking a rigorous biodiversity baseline study for the deep-sea environment.

This pattern—external actors driving their own agendas rather than responding to locally defined and articulated priorities—is not unique.

A decade earlier, Japan’s own ProSAVANA project in northern Mozambique followed a similar path. Launched in the early 2010s by the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) with Mozambican and Brazilian partners, it aimed to convert land to agricultural use, particularly soybean cultivation for export to Japan. Modeled on Brazil’s Cerrado “green revolution” of the 1970s, it was promoted as a way to promote agricultural and economic development in Mozambique.

In reality, the project facilitated land grabs covering 14 million hectares in the Nacala Corridor, displacing small farmers. Civil society groups denounced the opaque consultation process and backed local farmers’ resistance. After years of protest, the Japanese government ended its involvement in July 2020, belatedly acknowledging these concerns.

Both Mozambique LNG and ProSAVANA demonstrate how “development” promoted from the Global North can harm communities and the environment. When public finance is involved, the risks—and the responsibility—are even greater.

Better outcomes require meaningful, transparent consultation with affected communities, robust due diligence, and genuine accountability. Without these, development risks becoming extraction by another name.

As leaders gather at TICAD to shape Africa’s future, we urge Japan and all participating governments and businesses to focus on the needs and aspirations of African people themselves, and to avoid—or even redress—the mistakes of the past.

The question remains as urgent as ever: Who is this development really for?

If the Global South acts now, it can help build a future where algorithms bridge divides instead of deepening them—where they enable peace, not war.

The world stands on the brink of a transformation whose full scope remains elusive. Just as steam engines, electricity, and the internet each sparked previous industrial revolutions, artificial intelligence is now shaping what has been dubbed the Fourth Industrial Revolution. What sets this new era apart is the unprecedented speed and scale with which AI is being deployed—particularly in the realms of security and warfare, where technological advancement rarely keeps pace with ethics or regulation.

As the United States and its Western allies pour billions into autonomous drones, AI-driven command systems, and surveillance platforms, a critical question arises: Is this arms race making the world safer—or opening the door to geopolitical instability and even humanitarian catastrophe?

The reality is that the West’s focus on achieving military superiority—especially in the digital domain—has sidelined global conversations about the shared future of AI. The United Nations has warned in recent years that the absence of binding legal frameworks for lethal autonomous weapons systems (LAWS) could lead to irreversible consequences. Yet the major powers have largely ignored these warnings, favoring strategic autonomy in developing digital deterrence over any multilateral constraints. The nuclear experience of the 20th century showed how a deterrence-first logic brought humanity to the edge of catastrophe; now, imagine algorithms that can decide to kill in milliseconds, unleashed without transparent global commitments.

So far, it is the nations of the Global South that have borne the heaviest cost of this regulatory vacuum. From Yemen to the Sahel, AI-powered drones have enabled attacks where the line between military and civilian targets has all but disappeared. Human rights organizations report a troubling rise in civilian casualties from drone strikes over the past decade, with no clear mechanisms for compensation or legal accountability. In other words, the Global South is not only absent from decision-making but has become the unintended testing ground for emerging military technologies—technologies often shielded from public scrutiny under the guise of national security.

Ultimately, the central question facing humanity is this: Do we want AI to replicate the militaristic logic of the 20th century—or do we want it to help us confront shared global challenges, from climate change to future pandemics?

But this status quo is not inevitable. The Global South—from Latin America and Africa to West and South Asia—is not merely a collection of potential victims. It holds critical assets that can reshape the rules of the game. First, these countries have youthful, educated populations capable of steering AI innovation toward civilian and development-oriented goals, such as smart agriculture, early disease detection, climate crisis management, and universal education. For instance, multilateral projects involving Indian specialists in the fight against malaria using artificial intelligence.

Second, the South possesses a collective historical memory of colonialism and technological subjugation, making it more attuned to the geopolitical dangers of AI monopolies and thus a natural advocate for a more just global order. Third, emerging coalitions—like BRICS+ and the African Union’s digital initiatives—demonstrate that South-South cooperation can facilitate investment and knowledge exchange independently of Western actors.

Still, international political history reminds us that missed opportunities can easily turn into looming threats. If the Global South remains passive during this critical moment, the risk grows that Western dominance over AI standards will solidify into a new form of technological hegemony. This would not merely deepen technical inequality—it would redraw the geopolitical map and exacerbate the global North-South divide. In a world where a handful of governments and corporations control data, write algorithms, and set regulatory norms, non-Western states may find themselves forced to spend their limited development budgets on software licenses and smart weapon imports just to preserve their sovereignty. This siphoning of resources away from health, education, and infrastructure—the cornerstones of sustainable development—would create a vicious cycle of insecurity and underdevelopment.

Breaking out of this trajectory requires proactive leadership by the Global South on three fronts. First, leading nations—such as India, Brazil, Indonesia, and South Africa—should establish a ”Friends of AI Regulation” group at the U.N. General Assembly and propose a draft convention banning fully autonomous weapons. The international success of the landmine treaty and the Chemical Weapons Convention shows that even in the face of resistance from great powers, the formation of “soft norms” can pave the way toward binding treaties and increase the political cost of defection.

Second, these countries should create a joint innovation fund to support AI projects in healthcare, agriculture, and renewable energy—fields where benefits are tangible for citizens and where visible success can generate the social capital needed for broader international goals. Third, aligning with Western academics and civil society is vital. The combined pressure of researchers, human rights advocates, and Southern policymakers on Western legislatures and public opinion can help curb the influence of military-industrial lobbies and create political space for international cooperation.

In addition, the Global South must invest in developing its own ethical standards for data use and algorithmic governance to prevent the uncritical adoption of Western models that may worsen cultural risks and privacy violations. Brazil’s 2021 AI ethics framework illustrates that local values can be harmonized with global principles like transparency and algorithmic fairness. Adapting such initiatives at the regional level—through bodies like the African Union or the Shanghai Cooperation Organization—would be a major step toward establishing a multipolar regime in global digital governance.

Of course, this path is not without obstacles. Western powers possess vast economic, political, and media tools to slow such efforts. But history shows that transformative breakthroughs often emerge from resistance to dominant systems. Just as the Non-Aligned Movement in the 1960s expanded the Global South’s agency during the Cold War, today, it can spearhead AI regulation to reshape the power-technology equation in favor of a fairer world order.

Ultimately, the central question facing humanity is this: Do we want AI to replicate the militaristic logic of the 20th century—or do we want it to help us confront shared global challenges, from climate change to future pandemics? The answer depends on the political will and bold leadership of countries that hold the world’s majority population and the greatest potential for growth. If the Global South acts now, it can help build a future where algorithms bridge divides instead of deepening them—where they enable peace, not war.

The time for action is now. Silence means ceding the future to entrenched powers. Coordinated engagement, on the other hand, could move AI from a minefield of geopolitical interests to a shared highway of cooperation and human development. This is the mission the Global South must undertake—not just for itself, but for all of humanity.