SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

This week, AFL-CIO President Richard Trumka ran unopposed for the presidency of the AFL-CIO--but only because his opponent, labor activist Harry Kelber, died before the election.

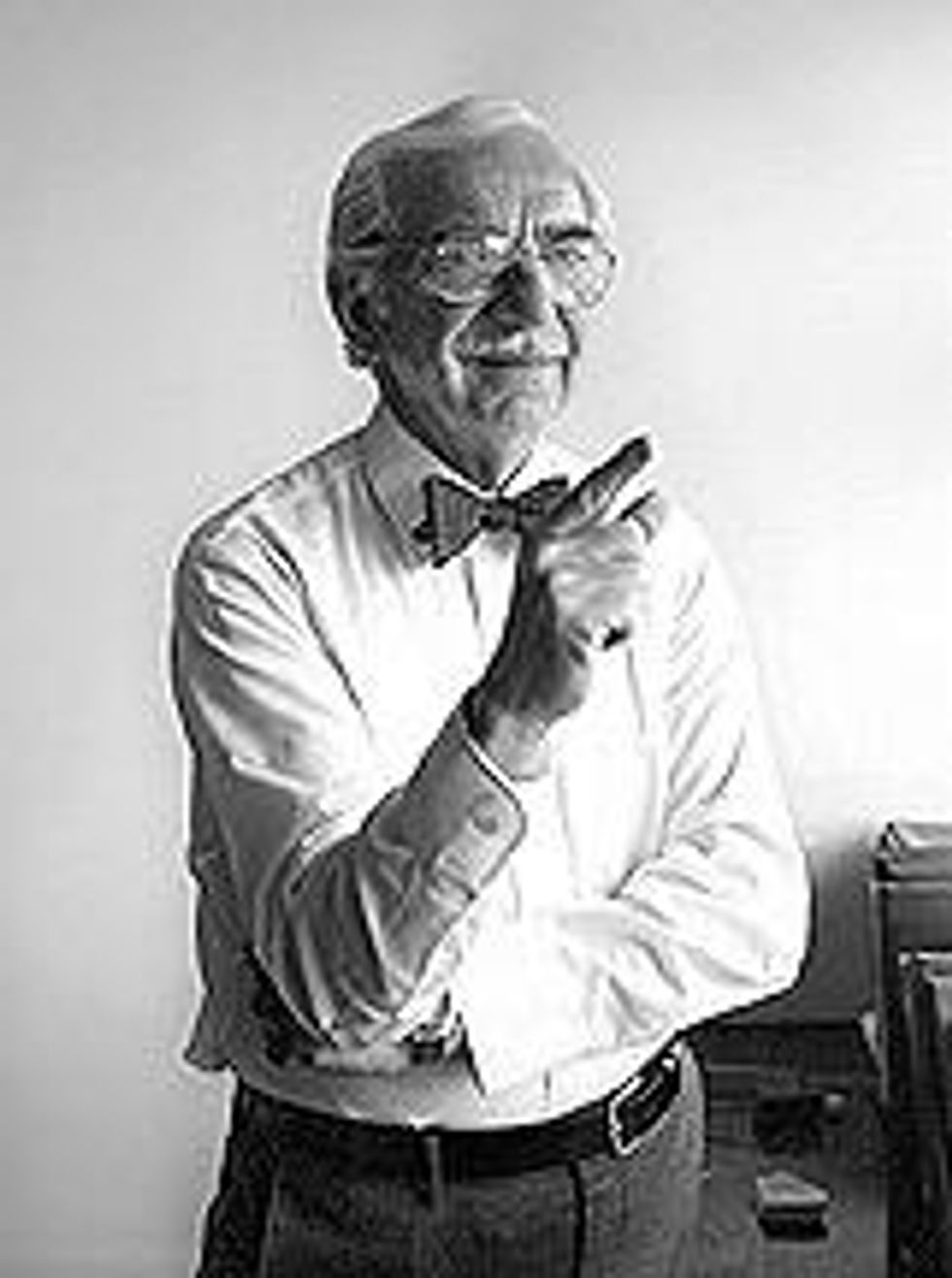

This week, AFL-CIO President Richard Trumka ran unopposed for the presidency of the AFL-CIO--but only because his opponent, labor activist Harry Kelber, died before the election. While foul play is not suspected (he died from natural causes in late March), the death of 98-year-old union dissident Harry Kelber still came as shock to me.

Harry had gotten so good at living, and at finding beauty and enjoyment in it, that I thought he would never die. Heck, so did he. "The way I figure it, I got enough money to make it till I'm 100," he used to joke.

Harry was a familiar figure at AFL-CIO conventions since 1995, when, at 81, he became the first ever rank-and-file union member to run for executive council of the AFL-CIO, forcing a contested election against incumbent President Lane Kirkland, whom he saw as ineffectual.

After that, he ran for AFL-CIO president four times, ensuring he had a speaking slot at the quadrennial convention--often the only time criticism of the AFL-CIO was heard from the podium during an otherwise tightly choreographed event. Harry considered the AFL-CIO leadership to be a group of "self-serving, self-perpetuating bureaucrats" disinclined toward the kind of tumultuous debates that empowered CIO activists to make the massive organizing gains that they did in the 1930s. "Win or lose, the Trumka group is guaranteed their six-figure salaries and lavish pension deals when they retire," wrote Harry last April. "And they use whatever tactics are necessary to prevent interlopers from challenging their power." (Harry loved to bring up that AFL-CIO President Richard Trumka made $293,750--dramatically more than the salary of a typical union member.)

Harry was constantly searching for ways to impart upon younger generations the lessons of dissent, criticism and reflection that he felt were so crucial to the organizing tactics of the CIO of the '30s. United Electrical Workers (UE) Political Action Director Chris Townsend used to say that Harry had forgotten more about organizing then most people inside of the AFL-CIO ever knew.

As a reporter with three generations of family members involved with the UE and its rank-and-file tradition of democratic control and self-criticism, I found it refreshing to talk to Harry, especially compared to my conversations with the sometimes close-mouthed leaders of the labor movement. When I met him in 2010, he seemed like a connection to people like my then-recently deceased grandparents, whose stories of building the labor movement in the '30s inspired me to become a labor reporter.

Harry continued to write three columns a week well into his 90s, in a lively, open-to-critique style reminiscent of the early labor movement. In some ways, Harry Kelber was the Thomas Paine of a lagging labor movement. I've heard him credited with starting the discussion that eventually lead to the first-ever ousting of an AFL-CIO president, Kirkland, in 1995--and Harry often claimed that his landmark 1990 book, Why Unions Are In Trouble... And What They Can Do About It, sold over 125,000 copies.

For Harry, it was heartbreaking to see modern labor leaders fail in their promises to workers, because he knew firsthand the price workers have paid for the right to join a union. He often recalled seeing a group of old Jewish waiters beaten on a New York street corner in the 1930s just for demanding the right to unionize. And he recalled the joy of successfully leading his own four-month strike as a teenage grocery worker in 1933.

Harry wasn't shy about voicing his criticisms of labor leaders, even when it meant suffering the consequences. During the McCarthy era of the 1950s, he faced underemployment and blacklisting when he fell out of step with the union-backed purge of communism in its own ranks. In 1990, he was fired as Director of the Educational and Cultural Trust Fund of IBEW Local 3 after criticizing IBEW leadership.

What amazed me the most about Harry, though, was how he managed to balance his commitment to labor activism with interests that went far beyond his passion for workers' rights. Labor reporting can be downright traumatic sometimes--covering people losing their jobs for trying to join a union, losing their pensions in slick bankruptcy procedures, and sometimes even losing their lives in all-too-frequent accidental workplace deaths. It's often very depressing because it's just people trying to help themselves, and there is so little you can do as a journalist to help these people. And the contrast between rank-and-file shop floor activists and high-paid, inside-the-Beltway labor leaders can be even more depressing for those of us who write about the movement as a whole.

But Harry never let the ugliness of it all drag him down, because he could constantly escape into the beauty of his many hobbies.

"If I had just sat on that couch and watched TV, I would have been been dead 20 years ago," Harry told me once. "I wake up in the morning and I am excited for whatever I am going to learn that day."

Harry pioneered a new form of poetry, known as a septad, which consisted of 28 syllables arranged in seven lines. He studied foreign languages well into his 90s, despite the fact that he was only capable of traveling to the places where those languages were spoken in his mind.

When it became too difficult for Harry to see the keys on a normal keyboard, instead of giving up writing, Harry simply went out and got a keyboard where the keys were twice as large. I remember during the Egyptian Revolution in 2011, Harry called me up to his apartment in Brooklyn Heights and asked me to show him how to use Twitter at the age of 95 so he could follow what was going on.

"Wow, this is thrilling," Harry exclaimed, watching as the tweets of Egyptian activists in Tahrir Square scrolled down the computer monitor in his Brooklyn Heights flat.

Harry's energy was astounding. He would frequently stay up till 3 a.m. writing, reading, making music, exploring, or listening to philosophy tapes. Harry would always encourage me to call him, no matter what time it was, whenever I got stumped on a piece. I remember once calling Harry in February 2011 at 1 a.m. from Madison, Wis. to ask him what he thought of the massive protests in the streets. I sat on the phone with him for more than an hour, listening to his stories of massive strikes and demonstrations in the 1930s.

He always told me that learning new things and keeping his mind active was what kept him so ecstatic about life. When he told me he'd been taking lessons to learn how to compose music, I assumed that he meant he was writing music on the piano. In the summer of 2011, I visited him with a French friend who finally asked Harry what kind of music he composed.

"Avant-garde music," Harry said. "You know, on the computer?"

My jaw dropped--the guy was 96 and more of a hipster than me.

Harry knew that I had suffered from bouts of depression, and every time we spoke, he would constantly try to encourage me to follow a path that would help me become a very happy 98-year-old labor reporter like him--to develop a hobby, a passion, something that I loved and I could look forward to every day, no matter what.

"Mike, this stuff will kill you if it's all you do," he said. "You gotta have something that you do when you come home that is just beautiful and makes you think with a different part of your brain."

While there may have been other writers who inspired me more as a reporter, nobody has inspired me to pursue the kind of life I wanted to have away from the keyboard like Harry did. I've found my own form of escape clipping magazine artwork to make collages.

Sometimes doing collage work late at night, I find myself thinking about Harry. I think of him sitting at his oversized keyboard struggling to make avant-garde electronic music. I think of sitting around his massive Brooklyn Heights apartment as the 96-year-old labor reporter gave me, a 25-year-old kid, dating advice based on his first failed marriage. I think of the way Harry howled when he laughed, and it makes me smile. I miss my friend.