SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

Though it is little noted in discussions of this year's election, Senator Bernie Sanders's campaign has brought back the essential message of then-Senator Barack Obama's "Yes We Can" campaign of 2008. The core of that message is the word "we," in contrast with former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton's frequent use of "I." However this year's election turns out, the idea that the people -- not politicians -- are the most fundamental driver of change is back in the public discussion.

The contrast between "we" and "I" has old roots in the progressive tradition. Debates about "socialism" are a diversion -- both Sanders and Clinton have legitimate claims to be progressive. But they represent different strands of the progressive tradition: the expert tradition and the populist tradition.

"Whatever the outcome of the contest between Clinton and Sanders, the key to real change is the people."

Progressivism emerged in the late 19th century and early 20th century as a movement to roll back the excesses of Gilded Age capitalism. Progressives believed in a positive role for government in taming the market. They believed in the principle of social change. They valued science. They affirmed the intrinsic worth and dignity of human beings.

But as David Thelen, past editor of the Journal of American History and a leading historian of progressivism, argued in his essay "Two Traditions of Progressive Reform" and other works, beyond these general agreements were two different tendencies. One was oriented toward bureaucracy and expert decision-making; the other was more populist, focused on grassroots democracy and participation.

Donna Shalala -- longtime Hillary Clinton confidant, secretary of health and human services during President Bill Clinton's administration and now president of the Clinton Foundation -- expressed clearly the tenets of the expert tradition back in 1989, in "Mandate for a New Century," a now-famous speech she delivered as chancellor of the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Shalala called upon higher education to engage with the problems of the world, from racism and sexism to environmental degradation, war and poverty. She also voiced the view that scientifically trained experts -- "a disinterested technocratic elite" -- should be at the center of decision-making. As Shalala put it:

The idea of society's best and brightest in service to its most needy, irrespective of any particular political philosophy ... is an idea of such great elegance... We all need to see our gifted researchers set about the work that will eliminate the cripplers we face now as thoroughly, if not as swiftly, as our research eliminated juvenile rickets in the past.

Hillary Clinton's "fighting for you" channels these expert-driven ideas. It places Clinton in the role of savior of the disadvantaged and marginalized -- Shalala's "best and brightest in service to its most needy." Clinton's calls for collective effort also suggest expert consultation. "We've got to get our heads together to come up with the best answers to solve the problems so that people can have real differences in their lives," Clinton said in her concluding remarks in a debate with Sanders on February 4, 2016.

However, the democratic tradition of progressivism has long been animated by populist movements: labor union organizing, civil rights, educational reform, the struggles of farmers to keep their farms and other such crusades. Progressive intellectuals with a grassroots democratic bent like Jane Addams, John Dewey, A. Philip Randolph and Alain Locke all had strong ties to these movements. So too did Henry Wallace, Franklin Roosevelt's secretary of agriculture and then-vice president, who in 1942 delivered a speech entitled "Century of the Common Man." Wallace's speech explicitly challenged Life publisher Henry Luce's "American Century" essay of 1941, which claimed warrant for America as global policeman. Wallace's tenure as secretary of agriculture also encompassed a little-remembered but enormous effort to democratize decision-making around how American farmland is used, from 1938 to 1941. Detailed in Jess Gilbert's 2015 book Planning Democracy, this movement showed how participatory democracy could take place with government acting as an empowering partner to its citizens -- neither savior nor enemy.

If we are to reverse the deepening mood of discouragement and powerlessness in the nation, we need wide civic involvement, amounting to a democratic awakening.

This populist, small-D democratic tradition of progressivism was revived in the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s. It surfaced again in the community-organizing movement of the 1970s and 1980s, which fundamentally shaped a young Barack Obama in Chicago.

Obama took the message of grassroots democracy which he had learned from community organizing to the nation in the 2008 campaign, amplifying its themes and engaging millions of people. "I'm asking you not only to believe in my ability to make change," read the campaign website. "I'm asking you to believe in yours." The message was expressed in such memorable campaign slogans as, "We are the ones we've been waiting for," drawn from a song of the freedom movement of the 1960s. And it infused Obama's field operation. As Rolling Stone reporter Tim Dickinson noted, the goal was "not to put supporters to work but to enable them to put themselves to work, without having to depend on the campaign for constant guidance."

"We decided that we didn't want to train volunteers," Obama field director Temo Figueroa explained to Dickinson. "We want to train organizers -- folks who can fend for themselves."

After Obama took office, the democratic promise of his campaign remained largely unrealized. Indeed, after becoming president, Obama's language began to shift from "we" to "I." At the news conference marking the first 100 days of his administration, Obama was asked what he intended to do as chief shareholder of some of America's largest companies. "I've got two wars I've got to run already," he laughed. "I've got more than enough to do." This shift in pronouns paralleled the deactivation of the grassroots base of Obama for America (OFA), which had powered the campaign.

As of election night 2008, OFA included some 2.5 million activists in the My.BarackObama social network, four million donors and 13 million email supporters. After the election, the organization's name shifted to "Organizing for America," at which point a fierce argument erupted among campaign leaders. Deputy campaign manager Steve Hildebrand argued that the new OFA should become an independent nonprofit. Joe Trippi, campaign manager for 2004 Howard Dean race, observed that OFA and its supporters had many independents and some Republicans and shouldn't lose its cross-partisan qualities. Finally, David Plouffe, a key architect of the 2008 campaign was put in charge of OFA. He decided to incorporate the organization as part of the Democratic National Committee.

"The move meant that the machinery of an insurgent candidate, one who had vowed to upend the Washington establishment, would now become part of that establishment, subject to the entrenched, partisan interests of the Democratic Party," observed Rolling Stone's Dickinson. "It made about as much sense as moving Greenpeace into the headquarters of ExxonMobil."

Flash forward to 2016, and we find the Democratic campaign tapping into growing activism on many fronts -- from Occupy Wall Street and Black Lives Matter to action on climate change and local development. Bernie Sanders's core argument, that a grassroots movement will be necessary for real change, echoes the Obama 2008 message, both in its stress on participatory democracy and in its integration of a range of issues into a larger call for change -- "we" language, not "I" language. In his speech after the Iowa caucuses, Sanders said: "The powers that be... are so powerful that no president can do what has to be done alone... When millions of people come together... to stand up and say loudly and clearly, 'Enough is enough'... when that happens, we will transform this country." Should Sanders become president, he would pursue a broad activation of citizens. "Bernie Sanders has always identified with the populist side of progressivism," Huck Gutman, Sanders's chief of staff in the Senate from 2008 to 2012, told me.

It is still possible that Hillary Clinton could pick up themes from the Reinventing Citizenship project I coordinated with Bill Galston, deputy assistant for domestic policy to President Bill Clinton from 1993 to 1995, now of the Brookings Institution. Reinventing Citizenship proposed a number of measures to strengthen government as a partner of citizens in public problem-solving and the work of democracy.

Whatever the outcome of the contest between Clinton and Sanders, the key to real change is the people. The issues that the campaign has raised -- the power of Wall Street, economic inequality and stagnant wages, college debt, mass incarceration, universal health care, campaign finance reform, climate change and others -- will require citizen power on a large scale if fundamental change is to occur. There are also many other, large-scale issues, crucial to the fate of the nation, that scramble partisan lines: revitalization of the democratic purpose of education; local economic development in the face of radical technological change; the drug epidemic; and reweaving the social fabric in a time of eroding community ties, to name just a few. These are enormous challenges. If the Democratic debate continues and deepens the call for citizen activation, it could well catalyze civic efforts beyond the issues of the campaign.

It is also clear that the idea of "we" has found a resonant audience especially among young people. "Sanders gives young people a place in his campaign," wrote Elisabeth Bott, one of my students from the University of Minnesota. "For so many people, politics is tainted. Sanders's campaign restores the idea that politics can be a source of change. He understands that we live in a time of change and extreme injustice and wants to change that with the help of us all."

This idea is not Sanders's alone. Politics -- by the definition of the term dating from the Greeks until the modern era -- has long involved citizens of diverse views and interests learning to work together to solve common problems, create common good and negotiate a democratic way of life. If we are to reverse the deepening mood of discouragement and powerlessness in the nation, we need wide civic involvement, amounting to a democratic awakening.

In this election, perhaps we see its beginnings.

The protagonist of a long series of detective novels, the admirable Inspector Maigret, would see a mystery at the heart of what goes on in America. How is it that violence barely disturbs us, yet we protect ourselves against its manifestation by a massive state apparatus dedicated to searching through the lives of ordinary Americans?

For those who follow politics, the mystery can be posed in personal terms. How is it that a senator who opposed the widespread gathering of telephone records of American citizens can, as president, approve the continuation and expansion of just such a program?

President Obama has advisors, not just military and civilian but political. All of them have a vested interest in assuring that nothing goes wrong in small ways, even as they ignore things going wrong in large ways.

That is not to say that his advisors, and the President himself, don't feel an obligation to keep Americans safe from harm and to prevent American society from sliding towards a chaos of destructive violence. We are not contemporary Iraq, nor do we want to be.

But much of the ongoing intrusion into our civil liberties arises out of narrow political fear. If we are attacked by a terrorist, there will be hundreds of thousands of fingers of blame pointing to those in command. As if a president, the FBI or the Congress, can somehow be blamed for every strangely-firing synapse in the brain of an individual living in Topeka or Charlotte.

The politics of accusation, layered into the politics of personal destruction - to his implacable opponents, the president was not born in the United States, is a socialist and is determined to take away everyone's guns - has had a calamitous result. Those close to the White House are tenaciously determined prevent any new impetus to a right wing determined to destroy our first black president. Even if they have to destroy part of America to forestall such a possibility.

Fear, not wholly unjustified, has driven those in power and those who provide counsel to power to establish and expand domestic spying. If a bomb goes off on a bus in Seattle, if someone blows himself up in a restaurant in Abilene, if a crazed man shoots the mayor of Philadelphia, the president will be blamed. 'Why didn't we know? Why didn't we prevent this tragedy?' Our generals, our representatives in Washington, will suffer collateral damage.

And so the administration, backed up by a majority of the Congress, countenances and supports widespread spying on ordinary American citizens. But what they do is shaped by a fear not just irrational, but unjustified.

Their aim is not, as they claim to themselves, to prevent violent destruction. Every year in the past decade over 30,000 Americans have died as a result of firearms. Yet there is remarkably little desire to prevent this staggering and largely avoidable destruction of human life.

More Americans die as a result of guns in a month and a half than died on September 11th. For a decade, over 58,000 Americans have been injured each year by firearms: 73,883 in 2011, 73,505 in 2010.

The tragic events of this year's Boston marathon, which kept a nation transfixed and glued to their television screens (myself included), resulted in 5 deaths and 264 injuries. It is instructive to do the math: on average, more people die of gun violence in two hours, more are injured by guns in less than a day and a half, than were casualties in Boston.

Terrorism strikes a deep nerve. And that means that anyone who 'coddles' terrorists or 'does not take terrorism seriously' can all too readily be accused of not caring about the security of Americans.

It is the fear of blame and not the need to protect American citizens that motivates those in Washington to countenance the enormous information gathering that has been taking place. Better, they think, to track every American's phone calls, to tally every key stroke and web visit and email that you or I produce on our computers, than suffer the blame for a terrorist attack. Better to jail the whistleblower who let us know the huge dimensions of surveillance than to step back and ask what the heck we are doing.

The civil liberties we proclaim as part of the great heritage of our Founding Fathers go out the window when the distant possibility of terrorism is before us. And that possibility is purely abstract, not justified by a particular action or threat. Yes, we do have enemies abroad and maybe here at home, but the fact of life is that it contains risk.

Those who wrote our Constitution knew that. They had recently been through a bloody war with England and nasty arguments between different factions in America, yet they enshrined in our Bill of Rights an amendment protecting citizens from intrusive searches by their government.

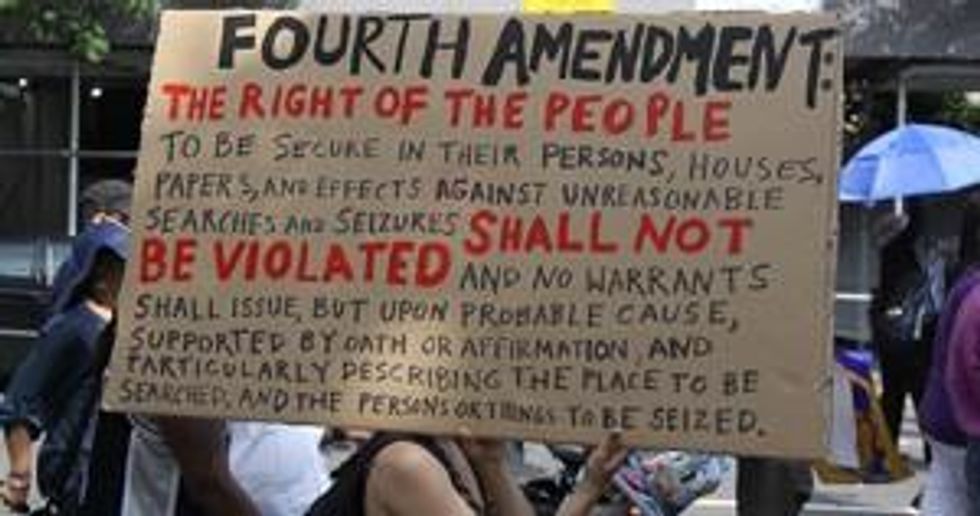

The 54 words of the Fourth Amendment are remarkably clear: "The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized."

But fear, the fear of being attacked politically (and not by terrorists), has led the Obama administration to ignore the Fourth Amendment and violate our rights to be secure in our houses (and on our phones). They have chosen to have our "papers, and effects" searched and in effect seized by the government. Does it matter that these papers are often in electronic texts, as documents in our files, or that our letters are mailed electronically rather than in a paper envelope? I don't think anyone can in good conscience answer in the affirmative.

There is not really a mystery to be unlocked. Our leaders are ruled by fear, fear not of violence but of blame. Recognizing that part of their fear is the result of right-wing efforts to invalidate the government, to bring down a duly-elected administration, does not justify acting in such a craven fashion.

We as a nation, we as citizens, deserve better.

Almost unnoticed last week, a federal judge ruled that a recent Maryland statute requiring Wal-Mart to spend more on health care was invalid under federal law.

The state required, through its Fair Share Health Care Fund Act, any employer with more than 10,000 Maryland employees to spend at least 8 percent of its payroll on worker health care. An employer who spent less would be obliged to pay the difference in taxes to the state. That money would be dedicated to a state medical assistance program.

Maryland's legislation was remarkably popular. A Washington Post poll found that 77 percent of registered voters supported it.

Those voters understand the simple truth: There is no free lunch. Any employer who does not pay for health insurance just passes its workers' medical bills on to others. Either to other employers in the form of higher premiums or to the taxpayers, who fund Medicaid. As the Speaker of the Maryland House, Michael E. Busch, observed, "When large employers don't provide health benefits, the rest of us pick up those costs."

His legislative colleague, Maryland Senate President Mike Miller was more blunt. "These guys are billionaires," he said, referring to the Walton family, which owns Wal-Mart. Christy Walton ranks as the sixth wealthiest American, with a fortune of $15.7 billion, tied with Jim Walton. Altogether, five of the ten richest Americans are Waltons, with close to $80 billion between them. That's more than Bill Gates and Paul Allen combined. "We're not going to let a big Arkansas corporation, protected by their contributions to the Republican Party, avoid their basic responsibility to the citizens of Maryland."

Someone pays for health care for Wal-Mart's employees -- only it often isn't Wal-Mart

The large retailers would rather defend stockholders who reap large profits than provide health care for their employees. So Wal-Mart, (and Target, and K-Mart, and Kohl's), in the guise of the Retailers Industry Leaders Association, took the Maryland legislation to court. They feared that the legislation would hurt their bottom line and that, if the Maryland legislation worked, many other states would enact similar laws. And they won in court.

"The decision sends a clear signal," warned Sandy Kennedy, president of the trade organization, "that employer health plans are governed by federal law, not a patchwork of state and local laws."

Kennedy read the District Court decision correctly. Judge J. Frederick Motz ruled, as he wrote, "in accordance with long established Supreme Court law that state laws which impose health or welfare mandates on employers are invalid under" the Federal Retirement Income Security act of 1974.

In other words, if it's broke, and our medical insurance system certainly is, the states shouldn't fix it.

But Judge Motz's ruling need not be the end of the matter.

If a federal law is needed, legislation should be introduced in the Congress -- and passed forthwith. Any corporate entity engaged in interstate commerce that has 1000 or more employees engaged would be required to spend at least 8 percent of its total wages on employee health care. (And let's include executive compensation, so those huge executive bonuses and stock options we read about so often have a real cost to the corporation.) Any corporation not spending 8 percent would have to make up the difference in a supplemental payment to Medicaid.

In addition, the law should go beyond what Maryland required not just by changing the numbers from 10,000 employees to 1000, but also by inserting a requirement for rough equality. All employees should have to receive some of the health care benefits -- they could not be distributed only to upper-echelon management in the form of Cadillac plans for some, and no health care for everyone else. Even part-time employees should be entitled to partial benefits.

Support for federalizing the Maryland law comes from an unexpected source. Counsel for the Retailers' Association Eugene Scalia, son of arch-conservative Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, told reporters after the ruling went in his favor, "Attempts to address the problem are going to require a federal response, not a patchwork of state and local mandates." Scalia acknowledged, "It's widely recognized that employers and employees need more assistance addressing problems with rising health-care costs."

How right he is. A federal response is needed. It's time to get the Wal-Marts, the K-Marts, the Hiltons, the Tyson Foods -- all those employers of clerks and chambermaids and chicken processors -- to start paying something for their workers' health care.