SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

"You feel like you are in the aftermath of a nuclear war," said one resident. "I saw an entire neighborhood disappear."

Undocumented migrants living in informal settlements in the French territory of Mayotte were among those whose lives and livelihoods were most devastated by Cyclone Chido, a tropical cyclone that slammed into the impoverished group of islands in the Indian Ocean over the weekend.

Authorities reported a death toll of at least 20 on Monday, but the territory's prefect, François-Xavier Bieuville, told a local news station that the widespread devastation indicated there were likely "some several hundred dead."

"Maybe we'll get close to a thousand," said Bieuville. "Even thousands... given the violence of this event."

Mayotte, which includes two densely populated main islands, Grande-Terre and Petite-Terre, as well as smaller islands with few residents, is home to about 300,000 people.

The territory is one of the European Union's poorest, with three-quarters of residents living below the poverty line, but roughly 100,000 people have come to Mayotte from the nearby African island nations of Madagascar and Comoros in recent decades, seeking better economic conditions.

Many of those people live in informal neighborhoods and shacks across the islands that were hardest hit by Chido, with aerial footage showing collections of houses "reduced to rubble," according toCNN.

"What we are experiencing is a tragedy, you feel like you are in the aftermath of a nuclear war," Mohamed Ishmael, a resident of the capital city, Mamoudzou, told Reuters. "I saw an entire neighborhood disappear."

Bruno Garcia, owner of a hotel in Mamoudzou, echoed Ishmael's comments, telling French CNN affiliate BFMTV: "It's as if an atomic bomb fell on Mayotte."

"The situation is catastrophic, apocalyptic," said Garcia. "We lost everything. The entire hotel is completely destroyed."

Residents of the migrant settlements in recent years have faced crackdowns from French police who have been tasked with rounding up people for deportation and dismantling shacks.

The aggressive response to migration reportedly led some families to stay in their homes rather than evacuate, for fear of being apprehended by police.

Now, some of those families' homes have been razed entirely or stripped of their roofs and "engulfed by mud and sheet metal," according to Estelle Youssouffa, who represents Mayotte in France's National Assembly.

People in Mayotte's most vulnerable neighborhoods are now without food or safe drinking water as hundreds of rescuers from France and the nearby French territory of Reunion struggle to reach victims amid widespread power outages.

"It's the hunger that worries me most. There are people who have had nothing to eat or drink" since Saturday, French Sen. Salama Ramia, who represents Mayotte, told the BBC.

The Washington Postreported that Cyclone Chido became increasingly powerful and intense—falling just short of becoming a Category 5 hurricane with winds over 155 miles per hour—because of unusually warm water in the Indian Ocean. The ocean temperature ranged from 81-86°F along Chido's path. Tropical cyclones typically form when ocean temperatures rise above 80°F.

"The intensity of tropical cyclones in the Southwest Indian Ocean has been increasing, [and] this is consistent with what scientists expect in a changing climate—warmer oceans fuel more powerful storms," Liz Stephens, a professor of climate risks and resilience at the University of Reading in the United Kingdom, told the Post.

People living on islands like Mayotte are especially vulnerable to climate disasters both because there's little shielding them from powerful storms and because their economic conditions leave them with few options to flee to safety as a cyclone approaches.

"Even though the path of Cyclone Chido was well forecast several days ahead, communities on small islands like Mayotte don't have the option to evacuate," Stephens said. "There's nowhere to go."

When I was in Paris, I met with Kathy Jetnil-Kijiner, a poet and young mother from the Marshall Islands. Kathy told stories of king tides breaking through her coral island's seawalls, with water quietly rising into her sleeping cousin's bedroom before a huge wave came and knocked her house over. (If her cousin's mother hadn't woken her, she would've went with it.)

I also met with Esau Sinook, an 18-year-old Inupiat Native American who lives on a barrier island called Shishmaref off the northwest coast of Alaska. The island is losing 3-4 meters of land a year and houses are falling into the sea.

"There is an incredibly powerful symbol right now in Europe: the boat. This is in the newspapers all the time. We know what that means. It means someone, in the poetry of it, putting everything they have into a small container and setting off, unsure of where we're going." --Kevin BucklandI also met Zara Pardiwalla, of the Seychelles, whose island home in the Indian Ocean faces saltier soil and bleached corals, meaning fishermen have to sail further and further out to find better catch.

Here's the rub: We don't know what to call these people. There is no label for Kathy or Esau or Zara on the international stage.

One of the most contested parts of the Paris negotiations was the issue of climate refugees. The U.S. removed compensation from the table before the talks even started. Still, even before the final draft, there was mention of forming a "climate displacement facility"—some entity that could help the folks staring out at Island-ruining waves. That got cut, too.

What made it into the Paris agreement is a pledge to "address displacement related to the adverse impacts of climate change," with a report back penciled for next year's summit in Morocco.

While this pledge is as watered down as you can get -- it also represents a lifeline. To understand how to seize it and why it took us so long to get here.

Erica Bower, an expert on "Loss and Damage" with the advocacy group Sustain US, told me that there is "no universal word to describe what it means to be forced to flee from your home." As a result, she said, "there have been so many debates in the last decade about definitions that it's stalled progress."

"Because people have been so fixated on having the right term, they don't actually act, they don't actually create the infrastructures that are needed to support these populations."

Some people want to use the phrase "climate migrants" while others want to use "climate refugees," and yet others want to use "disaster displaced person."

While "climate refugee" has the most punch to it, it's riddled with problems. As Bower explained it, one of those problems are that the phrase "climate refugee" implies sole causality when often climate change is an exacerbating force that worsens economic and political drivers (think: the Syrian refugee/war crisis and the 4-year record drought that preceded it).

Another major problem with the term "climate refugee" is it removes agency. According to Bower, "climate refugee" paints someone as a victim whereas people in Kiribati want to be described as "climate warriors" -- as people who have tremendous resilience and who will fight to stay in their country as long as they possibly can.

Without a name, it's been nearly impossible to rally for the world's first climate lost -- the people who are fleeing a planet that's gotten a lot tougher to live on. Kathy, Esau, and Zara still have homes, but since 2008, at least 22.5 million people were displaced each year because of sudden extreme weather events -- floods, typhoons, cyclones, and the like. That number is over double what it was in the 70s, and is a tenth of the 200 million climate-pushed migrants expected by 2050.

So, as we find footing after Paris, the question is: How do we find footing for the people who can't go home anymore?

The answer, I believe, lies somewhere at the juncture of an honest reckoning of loss, and a more nuanced struggle for justice.

As a movement, we've been stuck with the idea that we can fully and completely stop climate change. The waves of climate displaced--those we struggle to categorize or name properly--represent to at least some degree our failure as a movement to date. It's a failure we need to acknowledge, but more so it means that as we fight for the death knell of fossil fuels, we've now got to include justice for the survivors of a broken world for whom the renewable energy transition will simply come too late.

We saw the start of this evolution in Paris, where the final "D12" action included laying out long red canvas banners on the cobbled streets.

The red lines action began at the "tomb of the unknown soldier," where an eternal flame burns. People paid respect for climate change's victims—past and future—by dropping red tulips on the long banners.

The end of Paris showed a reckoning of human losses, an evolution from the naivete of saving the world, to trying to survive this one as best we can. While this work will include seeing through "the beginning of the end of fossil fuels," it now must also evolve into a global fight for the survivors -- for the displaced.

One other factor can help us seize the Paris lifeline. Symbols may offer a workaround since we've been stuck with clunky vocabulary.

Kevin Buckland, 350.org Arts Ambassador, described how symbols can act as containers for the losses and rallying cries we can't yet name.

Kevin told me about a new symbol that's been taking shape. "I think there is an incredibly powerful symbol right now in Europe, which is the boat," Buckland said. "This is in the newspapers all the time. We know what that means. It means someone, in the poetry of it, putting everything they have into a small container and setting off, unsure of where we're going."

New symbols that show humans in the crosshairs, like the boat, can maybe help us break the decade-long logjam to need the right words and incite the loud movement that is actually what we truly need to help the world's first climate homeless.

One of the oldest symbols of the climate fight, the polar bear, seems like it may have run its course.

At the end of our interview, Kathy, the Marshall Islands poet, told me:

"So, for people whose islands might be drowning, is that symbol not strong enough? Because polar bears are cute, you care more about them?"

"It's just incredible to me. I've never seen anything like this before."

That's what Jessica Blunden, a climate scientist with the National Ocean and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), told the New York Times in an interview following the agency's release on Wednesday of new figures showing that last month was the hottest September since records began and offered further confirmation that 2015 is on track to be the hottest year experienced in modern human history.

Dr. Blunden pointed the Times to measurements in several of the world's ocean basins, "where surface temperatures are as much as three degrees Fahrenheit above the 20th-century average," an increase described as "substantial" given the large size of these areas. "We're seeing it all across the Indian Ocean, in huge parts of the Atlantic Ocean, in parts of the Arctic oceans," she said. The bottom line, she added, is that "the world is warming."

As Andrea Thompson at Climate Central notes, the findings show that "September 2015 was not only the hottest September on record for the globe, but it was warmer than average by a bigger margin than any of the 1,629 months in [NOAA's records]--that's all the way back to January 1880."

NOAA's latest assessment on global temperatures arrives just weeks ahead of high-profile UN climate talks in Paris, where world leaders will once again come together with the stated goal of reaching an international agreement for addressing the runaway temperatures--and associated social, ecological, and financial costs--associated with global warming and climate change.

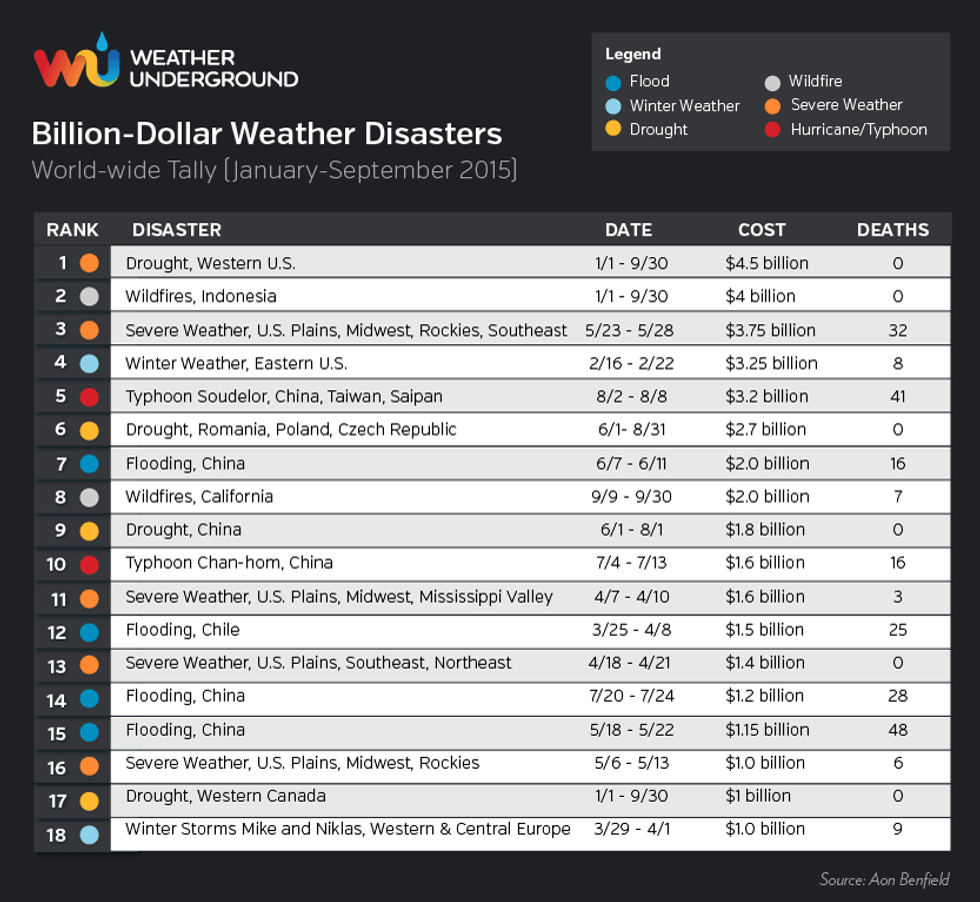

This table, published by the Weather Underground, cites statistics generated by insurance broker Aon Benfield. It shows that this year's record temperatures coincide with 2015, which has seen numerous "billion-dollar weather disasters," all of which were driven by or exacerbated by the climate fluctuations scientists have warned would correspond with increased warming of the world's oceans and atmosphere.

These trends, coupled with the myriad other dangers associated with life on a hotter planet, have focused much of the world's attention on what will transpire in Paris when the COP21 talks begin at the end of November.

According to a recent piece by Brad Plummer at Vox.com, however--given the gap between what governments are pledging for the talks and what the science demands--the outlook is not pretty. Encapsulating the current situation with a "good news vs. bad news" paradigm, Plummer put it this way: "The good news: Every country is submitting a detailed pledge to curb greenhouse gas emissions... The bad: Those pledges, added together, aren't nearly enough to keep us below 2degC of global warming. Short of drastic changes, we're in for some serious shit."

Meanwhile, commenting on developments at meetings in Bonn, Germany, this week where climate ministers were preparing a draft text for Paris, Susann Scherbarth, a climate justice and energy campaigner at Friends of the Earth Europe, said the world's richest and most polluting nations are wildly off-target when it comes to addressing the crisis.

"Emission-cut pledges made by rich countries so far are less than half of what we need to avoid runaway climate change," Scherbarth said. "The draft Paris agreement on the negotiating table this week shows that many seem ready to accept irreversible and devastating consequences for people and the planet."