SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

For places where livestock is deeply embedded in livelihoods and culture, it is critical to see these farm animals from our perspective and help channel climate and biodiversity finance into their potential as a force for good.

Livestock are a vital component of both the African food system and rural livelihoods. The continent has around 400 million cattle alone, and the livestock sector accounts for a significant 30-40% of the total agricultural gross domestic product across the continent.

Small amounts of meat, milk and eggs can have life-changing benefits in tackling malnutrition, and these animals also provide a reliable income source when alternatives simply do not readily exist.

Yet, from an environmental perspective, livestock are often perceived only as a problem, contributing to habitat loss, greenhouse gas emissions, and land degradation. This narrow view can hold back much-needed finance into the sector, yet it misses a much more nuanced reality.

International climate finance should prioritise support for sustainable livestock systems, recognizing their unique role in tackling broad environmental challenges while providing food, livelihoods, and economic growth.

As the United Nations prepares for three major environmental meetings over the next few months—on biodiversity conservation, climate change, and land management, respectively—it is important for the world to rethink how it perceives livestock in the context of development progress, and to begin to see such animals as cows, goats, camels, and pigs as “solutions with legs” in combating these intensifying climate and environmental crises at scale.

For countries like Kenya, where livestock is deeply embedded in livelihoods and culture, it is critical for U.N. meetings to see these farm animals from our perspective and help channel climate and biodiversity finance into their potential as a force for good.

Firstly, contrary to popular belief, livestock can be powerful agents of biodiversity conservation when managed correctly. Well-managed grazing systems help maintain ecosystems, control invasive species, and foster the regeneration of diverse native plant life in degraded areas. Pastoralist communities in Kenya, from the Maasai to the Samburu, have long understood this, using livestock grazing as a tool to balance ecosystems and promote biodiversity while providing essential sources of income and producing almost 20% of Kenya’s milk.

And in many conservancies, livestock are intentionally integrated into wildlife conservation strategies. Cattle are grazed rotationally, mimicking natural patterns seen in wild herbivores like zebras and gazelles. This approach helps prevent overgrazing, maintains healthy grasslands, and supports both livestock and wildlife populations.

Secondly, in terms of climate action, the role of livestock is often framed solely around their methane emissions, particularly in the case of ruminant animals like cattle. However, the potential for livestock to contribute to climate solutions is much broader, particularly in places like Africa.

In terms of mitigation, improved rangeland management and the adoption of climate-smart feeding practices can significantly reduce livestock-related emissions. For instance, integrating climate-resilient forages into grazing systems improves both productivity and environmental outcomes.

Moreover, sustainable grazing practices can play a crucial role in lowering the emissions intensity of meat and dairy production through carbon sequestration. Rangelands, often considered wastelands, are actually some of the planet’s largest carbon sinks. When managed properly, they store significant amounts of carbon in their soils, and proper management can contribute as much as 20.92 gigatons of climate mitigation by 2050.

On the adaptation front, livestock are a critical lifeline for communities facing increasing climate variability, including in Kenya’s arid and semi-arid lands. By moving their livestock across landscapes in response to rainfall variability, pastoralists effectively manage scarce resources while avoiding overgrazing.

This adaptive mobility, coupled with the use of Indigenous livestock breeds adapted to harsh climates, provides a critical buffer against droughts and other climate stresses—even more so when index-based livestock insurance is available. The East African Zebu cattle, for example, are better equipped to survive on limited, poor-quality forage in dry conditions, making them crucial to climate resilience in Kenya.

Lastly, as the global land degradation crisis worsens, it is becoming increasingly clear that sustainable livestock management can be a tool for land restoration and rehabilitation. Somewhere between 25% and 35% of rangelands globally suffer from some form of degradation. If left unattended, they become unproductive, reducing food security and driving people to abandon rural areas. Livestock systems can actually help reverse this trend by promoting soil health and regenerating landscapes.

Sustainable grazing practices, including rotational grazing and controlled stocking densities, allow grasslands to recover and restore soil fertility. By moving livestock strategically across the land, these practices prevent overgrazing and promote the growth of deep-rooted plants, which stabilise the soil and improve water retention. Furthermore, healthy rangelands support a wide variety of plant species, protect watersheds, and improve overall ecosystem resilience.

Which begs the question, if livestock are so critical to all these environmental issues, why does the sector receive so little funding? International climate finance should prioritise support for sustainable livestock systems, recognizing their unique role in tackling broad environmental challenges while providing food, livelihoods, and economic growth.

Livestock are not the enemy in this fight. Rather, they are an integral part of the solution, especially in places like Africa where pastoralist and livestock-keeping communities depend on them for survival.

If designating areas as World Heritage Sites endangers the survival of Indigenous peoples in African countries, UNESCO and IUCN’s outdated, colonial, and top-down approach to conservation must be dismantled immediately.

In the early morning of August 18, the safari cars that usually creep along the Ngorongoro-Serengeti highway, slowed by their sheer numbers, encountered a different challenge. Thousands of Maasai men and women, draped in red-patterned Shuka cloth and waving grass, a symbol of peace, were blocking the highway.

They were staging a peaceful protest against the Tanzanian government’s latest ruthless attempt to forcibly evict them from their ancestral lands. The police, wary of using violence in front of international tourists as they had in neighboring Loliondo in 2022, resorted to intimidation tactics instead, blocking vehicles carrying food and water from Karatu to the Ngorongoro Conservation Area (NCA) to weaken the resolve of the demonstrators.

“We are not blocking this highway out of choice. We are doing it for necessity. For too long our voices have been ignored, and out rights have been trampled. This is our last resort.”—Statement of the Maasai Community, NCA, August 18, 2024

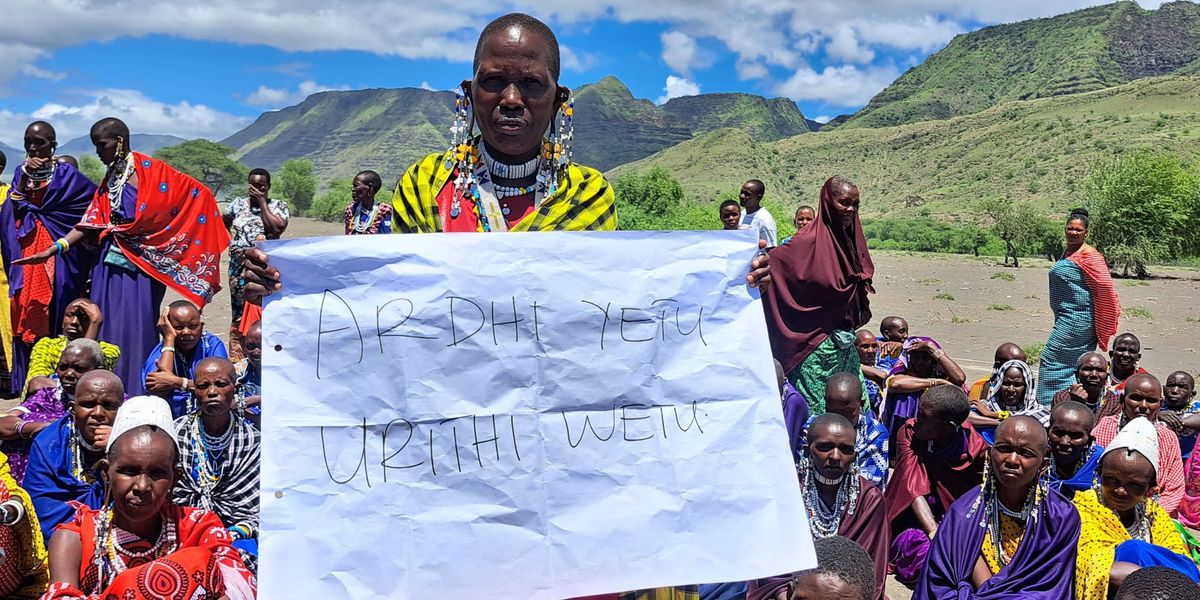

A Maasai woman holds a sign reading, “This is our ancestral land.” (Photo: The Maasai elders, NCA)

Since Tanzania’s colonizers established the Serengeti National Park in 1951—displacing Indigenous residents to Loliondo and the Ngorongoro Conservation Area (NCA)—the pastoralist Maasai in Northern Tanzania have faced relentless struggles against evictions and human rights abuses. For the past four years, their resilience has endured brutal attacks designed to expel them from their ancestral lands, transforming the region into a people-free zone to enhance safari tourism and hunting, as glorified in Western media like Planet Earth. These atrocities are masked as environmental conservation and protection.

In April 2021, the Tanzanian government announced the Multiple Land Use Management Plan (MLUM), posing a grave threat to the Maasai’s survival in the NCA. This followed the March 2019 joint monitoring mission by the UNESCO World Heritage Centre (WHC), the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), and the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS), which urged the government to control population growth in the NCA. The government responded by prioritizing tourism revenue, enacting the MLUM and a resettlement plan that expanded the NCA from 8,100 square kilometers to 12,083 square kilometers and created new restricted areas. In essence, this condemned nearly 80,000 Maasai to lives of destitution or death through forced evictions and the destruction of their livelihoods.

“The evictions and restrictions constraining tens of thousands of livelihoods are not about ensuring conservation but about expanding tourism revenues within the World Heritage Site. Tourism within the NCA has exploded in recent years with the number of annual tourists increasing from 20,000 in 1979 to 644,155 in 2018, making it one of the most intensively visited conservation areas in Africa. The number soared to 752,215 in 2023.”—The Oakland Institute

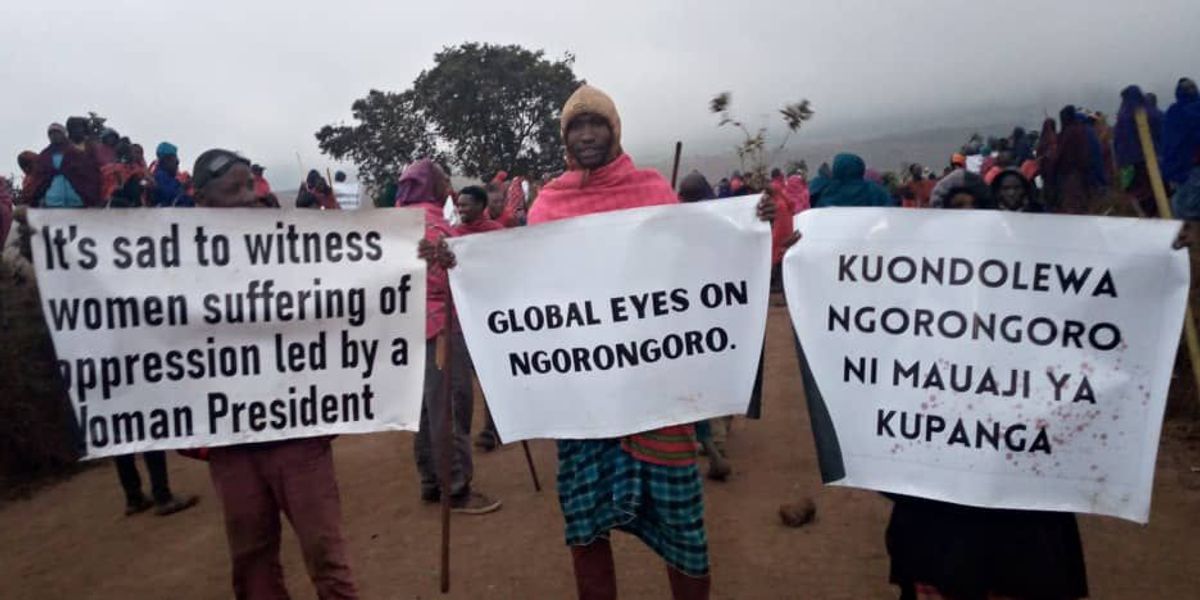

Maasai mobilize for their political rights. (Photo: The Maasai elders, NCA)

In response to international condemnation, the government falsely claimed that Maasai were volunteering en masse for resettlement at two relocation sites—Msomera village in Handeni district and Kitwai A and B villages in Simanjiro district. The flawed resettlement plans forced 11,000 Maasai community members from the NCA to send a letter to the government and its main donors stating their demand to remain in the NCA.

“This is not the first time that we are fighting to secure our rights and protect the lives of our people—we need a permanent solution and we need it now. We will not leave; Not Now, Not Ever!”—A Letter from Maasai Community to Tanzanian Government & International Donors, 2022

Despite the government’s claims that the Maasai’s relocation is voluntary, they have been forcibly uprooted by a systematic denial of essential social services, including education and healthcare. In May 2024, the government slashed nearly half of the budget for Endulen community hospital, the main healthcare provider for nearly 100,000 Maasai pastoralists in the NCA. These cuts ended vital support for facility repairs and community health initiatives. The grounding of the Flying Medical Service in 2022, after 39 years of critical emergency care, left over 24,000 children unvaccinated, deprived more than 5,700 pregnant women of necessary medical attention, and halted the delivery of life-saving HIV medications. While no official count of fatalities exists, it is undeniable that lives have been lost as a result.

Maasai hold protest signs on the Serengeti-Ngorongoro highway. (Photo: The Maasai elders, NCA)

In August, after failing to forcibly remove the Maasai from the NCA, the government struck a severe blow to their political rights. Ngorongoro Division was removed from the voters’ register, disenfranchising tens of thousands of Maasai pastoralists ahead of the upcoming local and general elections in 2025. Those registered to vote saw their polling station moved hundreds of miles away to Msomera village—the site of their forced relocation—effectively stripping even more Maasai villagers of their right to vote.

Adding to this assault on their political rights, Government Notice (GN) 673, issued on August 2, 2024, delisted 11 wards, 25 villages, and 96 subvillages in Ngorongoro Division, affecting over 110,000 people, all without obtaining their Free, Prior, and Informed Consent. This blatant violation of their rights sparked the August 18 protest, where Maasai residents demanded the reversal of GN 673 and the restoration of their electoral rights by the National Electoral Commission.

“We urge the Minister of Local Government to revoke and cancel Government Notice No. 673 of 2024, as it violates the constitution, laws, and international and regional treaties that Tanzania has signed and ratified.”—Onesmo Olengurumwa, National Coordinator, Tanzania Human Rights Defenders Coalition

As images of the Maasai, armed with grass and placards, demanding justice, went viral on August 22, 2024, the Arusha High Court temporarily suspended GN 673, pending further instructions. However, community lawyers have condemned the ruling as a sham. The court’s decision followed an injunction supposedly filed by Ngorongoro resident Isaya Ole Posi, who denies any involvement. Allegations have surfaced that the government paid the lawyer who filed the injunction against itself, in a calculated move to divert international attention sparked by the protests.

Stranded tourists stand watching the Maasai protests. (Photo: The Maasai elders, NCA)

While the Tanzanian government must undoubtedly be held accountable for violating the rights of its citizens, we must also scrutinize the role of two other key actors. The first are international conservation bodies like UNESCO, IUCN, and ICOMOS, under whose influence the government’s Multiple Land Use Model (MLUM) and resettlement plan were developed. It took an extensive global campaign to shift their stance. UNESCO’s website carries the government’s February 2024 report on the conservation status in the NCA, providing the false narrative that the relocation of local communities is voluntary, adheres to international best practices, and includes compensation measures. Yet, it also notes ongoing concerns from local communities, acknowledging the need for a human rights-based approach.

If designating areas like the NCA as World Heritage Sites endangers the survival of Indigenous peoples in African countries, UNESCO and IUCN’s outdated, colonial, and top-down approach to conservation—while boosting tourism—must be dismantled immediately. These institutions have reluctantly admitted that the NCA’s multiple land use model is appropriate, rather than altering its protected area category with disastrous consequences for residents. However, they have ignored calls for the NCA to be delisted from World Heritage sites and failed to pressure the government to stop its human rights violations.

As for the international tourists who continue to flock to Tanzania, lured by the chance to witness the “Big Five” or hunt trophies, the August 18 protests should serve as a wake-up call. The Maasai protesters and their global supporters have made their message clear: This is no longer a scene from “Out of Africa.” If there is no respect for Indigenous lives, then it must be “Tourism out of Tanzania!”

In recent years, the resilient and courageous Maasai communities of Tanzania have been faced with a challenge previously unmatched—“fortress” conservation.

We journeyed through the dirt tracks in the middle of the savanna—the vibrant crimson of the Maasai shukas making cardinal dots in the arid landscape. Zebras grazed in polyphony with cows, and the occasional giraffe paced gracefully, stretching its freckled neck towards the sky. Wildebeest and gazelles stampeded through the lands, a cloud of dust trailing behind them.

From the Serengeti to the Ngorongoro Conservation Area, the landscapes of northern Tanzania are mesmerizing. The Ngorongoro Crater, often referred to as the “eighth wonder of the world,” is a natural marvel—a massive volcanic caldera teeming with wildlife amidst many shades of lush golden hues. But what made this journey both heartfelt and heartbreaking was my time with the Indigenous Maasai who have traditionally inhabited the area, which in their mother tongue Maa is described as “the lands that run forever.” The complex but harmonious relationship between living creatures here is striking; the Maasai do not hunt the wild animals residing in the bush—they share the land with them.

For centuries, the Maasai have resided in the African Rift Valley, roaming the land with their cattle who graze on the available shrubbery and grass. Their deep connection to the land is woven into their identity, culture, and spirituality. This life has its challenges—the dry season being a perfect example of the elements they endure—harsh, scorching, dusty wind, with scarcity of water and grass for their cattle. But, in recent years, the resilient and courageous communities have been faced with a challenge previously unmatched—“fortress” conservation.

The Maasai face forced evictions from their homelands, where their traditional way of life is under attack. Their lives and livelihoods are getting buried under government plans for tourism and hunting desired by the foreign elites with “greed like hyenas,” as described by a Maasai village leader. This situation has sparked a fiery international debate on supposed conservationist goals, the rights of Indigenous communities, cultural preservation, and sustainable development.

Zebra graze in the savanna in Tanzania.

(Photo: Soleil-Chandni Mousseau)

The rationale behind the evictions that the Maasai face uses euphemisms of environmental, wildlife, and biodiversity protection. International conservation groups and the Tanzanian government justify “fortress” conservation by asserting that these measures are necessary to combat habitat destruction, poaching, and other environmental challenges.

Contrarily, villagers and community officials blame safari tourism as the cause of their plight. The tourism sector in Tanzania has ballooned rapidly—rising from $1.74 billion in 2004 to $4.48 billion in 2013. Today, it is second only to manufacturing in contributing to the country’s national income. This boom doesn’t seem to be stopping anytime soon; the Tanzanian government’s goal is to attract five million visitors annually to generate US$6 billion from tourism revenue.

A member of the Maasai community, whom I met in the Ololosokwan village, shared, “Tourists enjoy this beautiful landscape and wildlife that has been conserved by the Maasai pastoralists. And we face displacement.” Not honoring the true conservators—the Maasai—demonstrates the twisted logic of the Tanzanian government and the promoters of top-down neocolonial conservation models—tourists trump the livelihoods of the Maasai people.

Displacement from their ancestral lands has profound consequences for the Maasai. They are losing their livelihoods, social structures, and access to essential services like hospitals, water, and grazing lands for their cattle, and more. Disruption of their way of life is leading to increased poverty, loss of cultural identity, and disintegration of the communities’ social fabric.

An end to organized attacks on the Maasai’s traditional way of life is nowhere in sight. The government has not hesitated to use military force in villages, inflicting fear and chaos among the communities. On June 8, 2022, during the demarcation of 1,500 square kilometers (approximately 579 square miles) for a game reserve in Loliondo, community members who were protesting were shot at. Dozens were severely injured, including an 81-year-old who remains missing. Thousands, especially women and children, were forced to flee to the border with Kenya, facing the challenges of homelessness and displacement. Twenty-five Maasai villagers, including 10 local district councilors, were arrested and kept in jail for months on false charges. One of the arrested leaders spent six months in prison—away from his then-pregnant wife and his sons. He shared, “I had two prisons. One that I lived in and one of my thoughts, as I think of her [my wife]. The baby was born when I was in jail.”

Though they face severe hardships, the resilience and bravery of the Maasai shines through. In May 2022, a group of villagers went to Germany, one of Tanzania’s colonizers, to advocate for their human and land rights. They met with the Frankfurt Zoological Society, which continues to play a key role in promoting the neocolonial conservancy agenda that devastates countless lives. They would have five to six meetings each day, informing people on what the Maasai face as they struggle for their future. “I spoke for the Maasai community who undergo these sufferings,” said one of the participants of this trip.

Another village representative powerfully stated, “They take my land. They take my life. If land is taken—it is the end of life.”

A member of the Maasai community in Tanzania points into the distance.

(Photo: Soleil-Chandni Mousseau)

The forced evictions of Indigenous communities contradict the principles of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which recognizes their rights to self-determination, to land, and other vital resources. It also undermines the goal of achieving sustainable development, as the well-being of both the environment and the people living within it are connected. Critics of the “fortress” conservation model argue that these evictions are not only an infringement on the Maasai’s human rights, but that they are also counterproductive to conservation efforts. The Maasai people’s traditional knowledge, built over centuries, contributes to sustainable land management practices that help preserve biodiversity and prevent environmental degradation.

As the summer comes to an end, and the reality of junior year looms over me, I think less about my college admissions and exams. My experience in Tanzania not only gave me photographs and souvenirs, but a profound appreciation for the true stewards of the land, the Indigenous Maasai—for whom land is life. Their sacred connection to the land and their commitment to preserving it is a powerful reminder of what true conservation is.

As I return to the Bay Area—in my privileged bubble of air conditioning and concrete roads, dogs in strollers, and six-lane highways—I hold on to the Maasai’s powerful words. Their resilience fuels my determination toward continuing to learn about their struggle to protect the delicate balance between humanity and nature, while challenging this form of neocolonialism—another chapter of the West scrambling to get a fraction of Africa’s eternal wealth and beauty.

The author stands with two members of the Maasai community.

(Photo: Soleil-Chandni Mousseau)