"We are all working so hard in our own areas," O'Meara Sanders told Common Dreams after the event wrapped up on June 2. "It allowed people to get out of the silos that too often separate the policymakers. So to have elected officials and advocates in so many different areas, having them be able to come together and discuss different things... it bodes well for the future."

Over three days filled with more than 15 livestreamed panel discussions, film screenings, and other events, participants in the Gathering learned about how advocates in California are working to implement social housing, taking inspiration from countries like Austria and Spain; the labor rights movement's "25x2" strategy of pushing living wage legislation and ballot measures in dozens of states; and a number of reasons to be optimistic about fighting the climate crisis—even as scientists warn the continued burning of fossil fuels will push global temperatures past 1.5°C of heating in at least one of the next five years.

Climate

Despite experts' bleak projections, McKibben and Sierra Club executive director Ben Jealous welcomed guests on the first night of the conference by offering evidence that electric vehicles and solar panels are rapidly becoming more powerful and more accessible to more U.S. households, providing hope that the world's largest historic emitter of carbon dioxide is making strides to cut down on planet-heating pollution from transportation and electricity.

"Right now, the sea surface temperature in the Atlantic is two to three degrees higher than we've ever seen it before," said McKibben. "And at the exact same moment that the planet is physically starting to disintegrate precisely the way the scientists 30 years ago told us it would—as if scripted by Hollywood—you'll also see finally the sudden spike in... the only antidote we have at scale to deal with this: the application of renewable energy around the world."

"Last summer, just as scientists were telling us that it was the hottest week in the last 125,000 years, that same week was the week that the engineers told us that for the first time, human beings were now installing more than a gigawatt's worth of solar panels every single day on this planet," he added. "That's a nuclear power plant's worth of solar panels. So we are right at the moment when one or the other of these trends is going to cancel out... the other one. Our job, I think, is to make sure that we figure out how to dramatically accelerate that second trend so that we have some hope of catching up with the physics of climate change before it does in everything that we care about on this planet. So for me, that's the context of the moment that we're in."

That theme—giving guests at the Gathering an unvarnished accounting of the very real crises that face communities while providing a glimpse into campaigners' ongoing efforts and positive results of their tireless advocacy work, with the crucial help of progressive lawmakers like Sen. Sanders—continued throughout the weekend.

Joseph Geevarghese of Our Revolution, The Hip Hop Caucus' Rev. Lennox Yearwood, Jamie Minden of Zero Hour, and Friends of the Earth U.S. president Erich Pica. (Photo: Will Allen / via The Sanders Institute)

Joseph Geevarghese of Our Revolution, The Hip Hop Caucus' Rev. Lennox Yearwood, Jamie Minden of Zero Hour, and Friends of the Earth U.S. president Erich Pica. (Photo: Will Allen / via The Sanders Institute)

On the climate front, advocates shared their hopes to seize on the opportunity of Republican plans to extend Trump-era tax cuts if they regain power in the November elections.

Participants on a Saturday panel at the Gathering—including Joseph Geevarghese of Our Revolution, the Hip Hop Caucus' Rev. Lennox Yearwood, Jamie Minden of Zero Hour, and Friends of the Earth U.S. president Erich Pica—argued that ending federal handouts to Big Oil is part of the broader effort to ultimately "kill the fossil fuel industry" that's cooking the planet while blocking the worker-led demand for a green energy transition.

Too often when covering advocacy work, the corporate media focuses on "the controversy," O'Meara Sanders told Common Dreams. "What's the controversy as opposed to what's the plan?"

The Gathering set out to offer an antidote to that dynamic and many participants—including Dr. Deborah Richter, board president of Vermont Health Care for All—said the effort was a success.

"Sometimes when you're trying to get some sort of major social change, it can get really, really strenuous and make you sad," Richter told Common Dreams. "I felt incredibly rejuvenated after this weekend."

"You tend to get single-focused when you're working on one issue," she added. "And I actually really appreciated the updates, the good and the bad on climate change... I came away thinking, I have to learn more about climate change. I'm going to learn more about this. I'm going to learn more about that."

Healthcare

Richter spoke to attendees about her group's efforts to bring government-funded healthcare to Vermont, noting that she has spent years advocating to expand Medicare to the entire population while also witnessing her own patients' struggles with the for-profit system as a primary care doctor and addiction medicine specialist.

Joining Richter for the panel discussion was Dr. Jehan "Gigi" El-Bayoumi, a Georgetown University School of Medicine professor who founded the Rodham Institute, which works to achieve health equity in communities across Washington, D.C.

"Many people think that what determines how long you live and how healthy you are is access to healthcare," El-Bayoumi told Common Dreams. While crucial, "that only accounts for 20%." The remaining 80% is other "social determinants of health," such as whether people live in a neighborhood with access to affordable, nutritious food and clean air or a fenceline community next to a chemical plant or oil refinery, raising their chance of developing respiratory problems or other health issues.

"Health is the air that we breathe. Health is what we eat and where we live," El-Bayoumi said, noting that the same factors are also "the social determinants of education and the social determinants of employment."

"If you don't have those things in place," the physician continued, "then how are you going to have better health?"

In Burlington, El-Bayoumi spoke about efforts to ensure people of color in Washington, D.C. had access to Covid-19 vaccines when they were first introduced. Working with the Black Coalition Against Covid, she partnered with medical schools at historically Black universities, Black fraternities and sororities, the hip-hop community, and others to hold a mass vaccination event in Ward 8.

"Community needs to be at the table," she told the audience. "The people that are closest to the problem know the solutions."

El-Bayoumi stressed to Common Dreams the importance of not only engaging with impacted community members but also following the lead of success stories around the world. While progressives often cite European examples, she pointed to models such as the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease's Project Axshya, which set up nearly 100 tuberculosis treatment and information kiosks in 40 cities across India.

She also cited models from Egypt, Namibia, and Zimbabwe, where the Friendship Bench project trained elder volunteers without any formal medical credentials to discreetly counsel patients on wooden benches on the grounds of clinics, aiming to address "kufungisisa," the local word closest to depression.

When it comes to providing healthcare, "we're all spokes on a wheel," El-Bayoumi said. "The nurses and the physicians and the custodians... we're all spokes. We could not function without each other."

"But then similarly, health, environment, food, political, education—all spokes on a wheel," she added. "There is not one thing that's more important."

Housing

The latest Gathering built on the institute's April conference on housing justice—an event that brought together leaders in Los Angeles, including the city's Mayor Karen Bass, California Assemblyman Alex Lee (D-25), and U.S. Reps. Pramila Jayapal (D-Wash.) and Ro Khanna (D-Calif.).

Lee also attended the Burlington conference, where he spoke on a panel with Michael Monte of Vermont's Champlain Housing Trust and AIDS Healthcare Foundation president Michael Weinstein, who argued that "housing is not high enough on the progressive agenda."

"Our job as progressives is to do everything we can every day to make people's lives materially better, and this is an area that we have to focus on," Weinstein said, echoing his remarks during the 2018 Gathering, the very first such event hosted by the institute.

In terms of actually getting people into affordable homes, "we could do a lot to make it less bureaucratic," he said—touching on a topic that dominated a second housing crisis panel.

For that discussion, O'Meara Sanders was joined by Brian McCabe, deputy assistant secretary for policy development at the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, and Nika Soon-Shiong of the Fund for Guaranteed Income (F4GI), which provides "cash transfers that support those who have been locked out of welfare programs and economic systems."

F4GI is also working on a pilot program to provide a "cash on-ramp" to help people who are participating in the federal Housing Choice Voucher Program, commonly called Section 8, while they search for rental units, Soon-Shiong explained.

She stressed the importance of including community members in the development and implementation of the programs designed to help them, and pushed back against common messages about financial and logical hurdles.

"Part of addressing the root cause of the housing crisis is actually removing that false frame," she said, "and demonstrating that it's possible to collaborate, to move quickly, and to design things that are new and actually relatively inexpensive."

Workers' Rights

During one of the labor panels, Jayaraman of One Fair Wage spoke about the nationwide fight for better pay and working conditions—and how the movement's wins had provoked threats to her and her family.

El-Bayoumi said that before Jayaraman's remarks, she knew a bit about restaurant workers' fight for higher pay due to experiences living and working in Washington, D.C.—where residents passed ballot measures to raise the minimum wage for tipped employees in 2018 and 2022.

"What did I not know? Always scale," the physician continued. She was struck by the specifics that the labor leader shared, as well as her perseverance while being attacked for being successful.

"She was so inspiring and invigorating… She was raw. She was real. I'm just a great admirer now, and I learned a lot from her," El-Bayoumi said. "Her energy was amazing... It was the information, but also her commitment."

One Fair Wage co-founder and president Saru Jayaraman during a speech at The Gathering. (Photo: Will Allen / via The Sanders Institute)

One Fair Wage co-founder and president Saru Jayaraman during a speech at The Gathering. (Photo: Will Allen / via The Sanders Institute)

During her speech at the Gathering, Jayaraman said the fight being fought by the millions of low-wage workers her group represents, many of whom work two or even three jobs just to stay afloat, are crucial if the progressive movement more broadly wants to win the battles on climate, healthcare justice, and housing.

"It's not a competition with all of our issues," Jayaraman said, "because if these folks could work one job instead of two or three, they would have the capacity to work on healthcare and climate change and everything else. I asked them, 'What would you work on if you could only work one job?' They've said climate. They've said public education. They've said, 'I would do so much, but I have time to survive right now. I just have to get from job to job.'"

So if the question is what's the problem and what's the opportunity, Jayaraman said, "The opportunity is this November—we have 3.5 million workers get a raise and then turn around and work on all of the issues everybody else cares about in this room."

Media & Technology

At a panel on progressive news media, The Nation national affairs correspondent John Nichols spotlighted another labor struggle that has national and global implications, as U.S. newsrooms lose thousands of working journalists to layoffs and budget cuts—frequently stemming from private equity firms purchasing newspapers and then looking to raise revenues at the expense of the reporters whose work the outlets rely on to operate.

"Since 2005, we have lost 45,000 working journalists in this country," said Nichols. "So we have a collapse of journalism. We have no filling of the void, and the institutions themselves are collapsing. Since 2005, roughly 20 years, we have lost a third of all print and online publications that existed at that time."

Nichols, who edited Sanders' book, It's OK to Be Angry About Capitalism, and spoke on the senator's podcast in April about the current crisis in media, was joined by The Lever founder David Sirota and Common Dreams managing editor Jon Queally.

"We are in a period where our media in this country is in such crisis and such collapse and such dysfunction that it is no longer sufficient to sustain democracy itself," Nichols told the audience.

As traditional newsrooms across the country struggle to survive in an industry increasingly dominated by private equity firms and hedge funds, Sirota spoke about starting an online investigative news outlet with the aim of breaking news stories that might otherwise go uncovered by large publications—or that might be reported on briefly, with the stories of the people affected forgotten within a few days.

After a Norfolk Southern train carrying toxic chemicals derailed in the town of East Palestine, Ohio, Sirota said, The Lever "broke open a story that looked back at what were the decisions on specific policies that were made to create an environment for a disaster like that to happen, and which politicians took money at the time while they were making those decisions."

The Lever reported on how Norfolk Southern lobbied lawmakers to repeal a rule requiring widespread use of electronic braking systems, which were meant to help avoid accidents, and how the Trump administration rescinded the rule in 2017 after the rail industry donated more than $6 million to GOP candidates.

"Ultimately, our reporting ended up playing a big role in getting the Senate and the House to introduce major rail safety legislation that had specific provisions in it that dealt with exactly what we were reporting on," said Sirota. "The New York Times asked us to do a full page op-ed about our reporting... That's how elevated it became."

"The reason to do that is not for our own glory," he added. "It's ultimately to shape what actually happens moving forward. So our goal is to hold accountable those who are making these decisions with the hope that if they are held accountable, they will be deterred from making such bad decisions in the future."

In addition to the media, the Gathering featured panels on civil discourse and technology. During the latter discussion, which addressed topics including artificial intelligence and data collection, journalist Sue Halpern pointed out that in Congress, "there's a tension between... wanting to protect us—theoretically—and commerce."

She suggested that corporate pressure is blocking bipartisan efforts to pass federal privacy legislation, explaining that "the lobbyists for the Big Tech companies are constantly saying to lawmakers... if you regulate this, if you pull back on this, you will harm the American economy and you will limit innovation. And I have to say that most congresspeople are terrified of being accused of limiting innovation."

"Congress can't get it together to make national legislation. And so we see kind of a piecemeal thing going on, at least with privacy," Halpern said, highlighting laws passed by California, Illinois, and recently, Vermont, that serve as models for other states, in the absence of federal action.

Screenings

Along with panel discussions, the Sanders Institute incorporated film screenings and music into the Gathering to offer attendees another avenue into some of the issues discussed.

Kelton, an economist at Stony Brook University, presented a film spotlighting efforts by her and several colleagues to prompt a "paradigm shift" in Americans' understanding of the national deficit by introducing the public to Modern Monetary Theory (MMT).

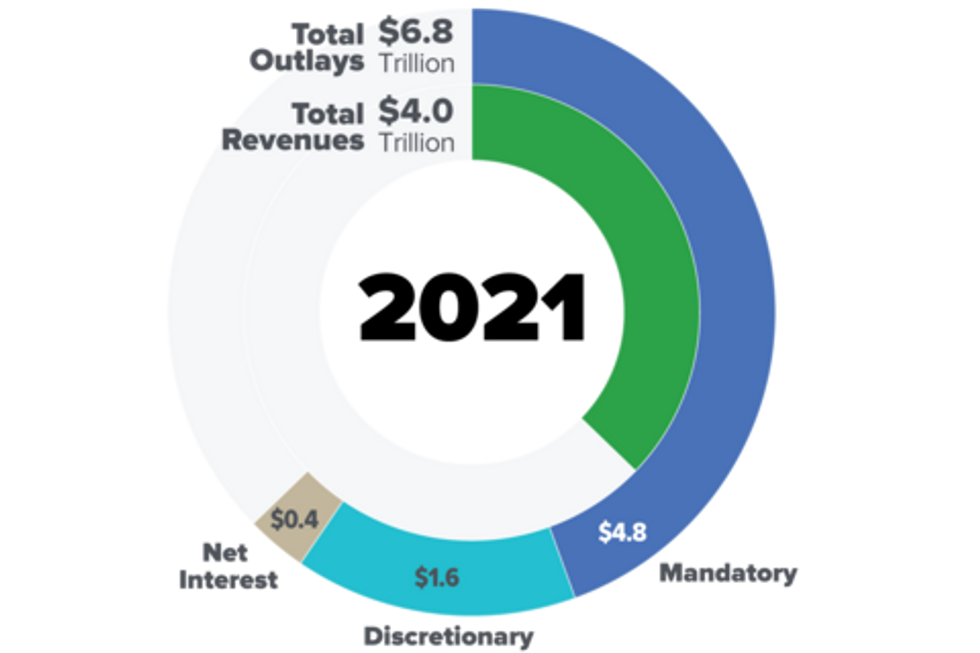

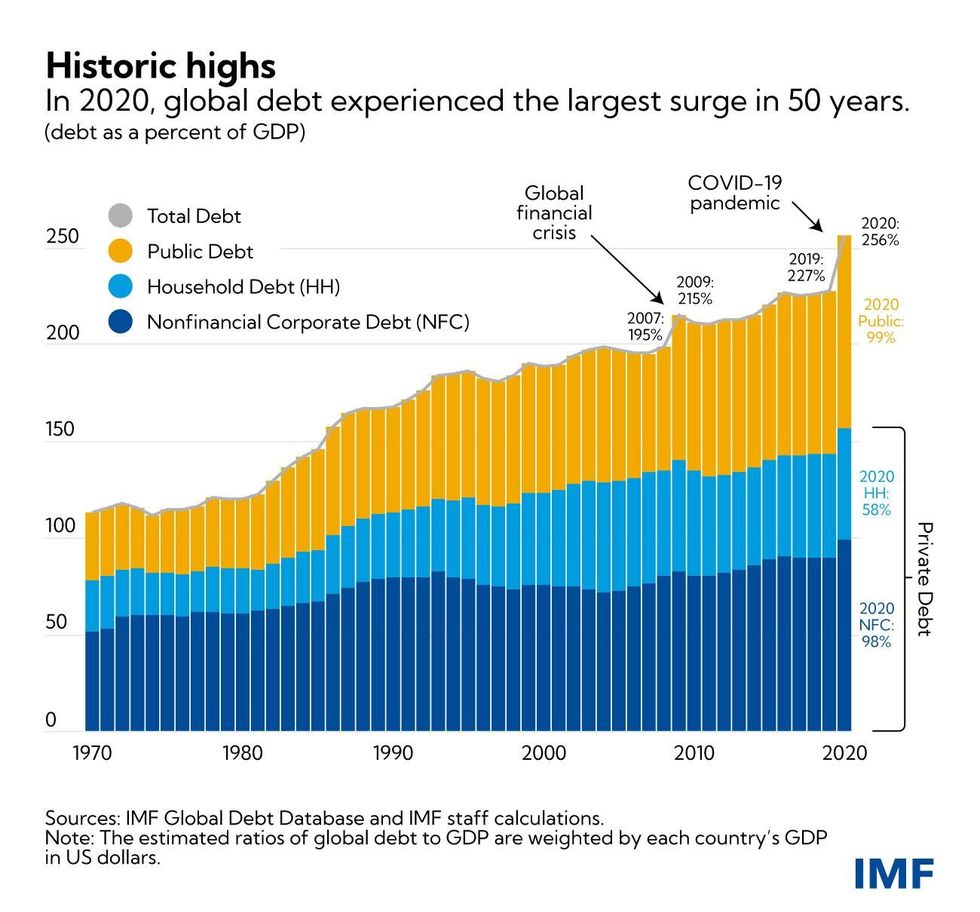

Directed by Maren Poitras, Finding the Money follows Kelton and economists including Randall Wray as they explain their vision for how the national debt could be viewed not as a burden that American taxpayers must pay back through cuts to government programs, but "as simply a historical record of the number of dollars created by the U.S. federal government currently being held in pockets, as assets, by the rest of us."

Kelton questioned how the Republican Party can, year after year, name reducing the federal deficit as one of their top priorities when the tax cuts introduced by the GOP under the George W. Bush and Trump administrations have been the primary drivers of the increasing debt ratio in recent years.

"They don't care about the fiscal or budgetary impacts. They want to pass their agenda. So we get sweeping tax cuts," Kelton said. "[The Congressional Budget Office] says the tax cuts will add $1.9 trillion to the deficit. Republicans shrug and say, who cares? On the other side of the government deficit lies a financial windfall for somebody else. Every deficit is good for someone. The question is for whom and for what."

In the film, Kelton argues that as the issuer of U.S. currency, the federal government does not need to "find the money" to spend on public programs, but instead needs only to ensure that real resources like workers and construction supplies are available when it comes to spending. The government can avoid a surge in inflation through policy decisions, the economists in the film argue, but greater deficits in a large country like the U.S. are far more sustainable than Americans have been led to believe.

Along with the Bush and Trump tax cuts, Kelton used the relief packages passed by Congress when the coronavirus pandemic began in 2020. A total of $5 trillion in relief was passed through several laws, raising people's unemployment benefits and helping small businesses to stay afloat.

"We cut child poverty by roughly 40%, and you can talk on and on about the benefits, because every deficit is good for someone," Kelton said. "The question is for whom and where does the windfall on the other side of the government deficit go? In March of 2021, it went to the bottom... That's who it helped. The Republicans did $1.9 trillion with their tax cuts. Where did it go? Eighty-three percent of the benefits went to people in top 1% of the income distribution."

Now, said Kelton, the deficit should be seen as a way for the government to pass more far-reaching legislation to fight the climate emergency.

The weekend also featured screenings of trailers for filmmaker Josh Fox's The Welcome Table—which is about the climate emergency causing displacement and is set to be released on HBO—and The Edge of Nature, an evolving documentary project that connects the crises of Covid, climate, and healthcare.

Fox, known for the award-winning anti-fracking film Gasland, brought his banjo—signed by Sen. Sanders—to Burlington to preview a musical performance that accompanies The Edge of Nature, which he is bringing to New York City with a 12-person ensemble from June 14-30.

"I thought that his telling of his own experience with Covid and the healing power of nature is just so true," El-Bayoumi said of the performance. "I have patients who are just struggling with life, with mental health issues. I will tell them, go outside, take off your shoes, feel the ground under your feet, because nature is healing."

The Edge of Nature "actually gave me hope... which I think is one of the things that was brought up over and over again at the Sanders Institute Gathering," she added. "How do you present that, the issues and solutions, if you will. And I thought that he did that very well."

There was also a screening of a video produced by the Power to the Patients campaign, which has worked to educate the public about healthcare transparency requirements through murals painted in cities across the United States. While the auditorium was waiting for that video to start amid technical difficulties, the audience broke out in song, singing "Solidarity Forever."

"It was so beautiful. And that was an amazing moment to me," Fox told Common Dreams. "And it said to me, go ahead and sing your song in your presentation, because this is a room where you can sing."

"My takeaway was, we have our differences, and we definitely have our identities, and we have our priorities, and we have... teachable moments where we have to instruct each other as to how we're messing up," he said. "But also, we really need to focus on solidarity."

Sierra Club executive director Ben Jealous, filmmaker Josh Fox, and The Sanders Institute's Dave Driscoll listen to a presentation during the Gathering in Burlington, Vermont on Saturday, June 1, 2024. (Photo: Will Allen / via The Sanders Institute)

Sierra Club executive director Ben Jealous, filmmaker Josh Fox, and The Sanders Institute's Dave Driscoll listen to a presentation during the Gathering in Burlington, Vermont on Saturday, June 1, 2024. (Photo: Will Allen / via The Sanders Institute)

Fox noted that when he used to introduce Sen. Sanders during his 2016 presidential campaign, the filmmaker would say, "All the movements are in this room."

As he prepared for the NYC performances, Fox said that in the current "moment of division… the more we can come together in physical space—and that's what we're offering here with this show, a chance to be in an audience, a chance to be together, a chance to be in reality with each other—the better we can break those boundaries down."

"My takeaway from the Gathering is, I wish this was happening all the time and at the White House," he added, "but if it's not, we can recreate this in our small ways throughout this [election] cycle."

What's Next

O'Meara Sanders said the Sanders Institute intends to have one large Gathering each year and will continue to hold smaller events focused on specific issues, as it did in April with housing.

International Gatherings are one possibility, said O'Meara Sanders, expressing hope that some of the policymakers and advocates who shared their aspirations and plans for the United States in Burlington could convene with lawmakers in other countries who have been successful at implementing social housing, far-reaching climate action, and government-funded healthcare.

The institute aims to bring "members of Parliament together with members of Congress, to bring together diplomats from different countries," said O'Meara Sanders, "to talk about specific issues. Who's doing it best? How can we learn from them?"

"We're going to be bringing people together from all the different countries to explore what they're doing best and how we can do it better together," she added. "And then what's the political will necessary to accomplish these things?"

Joseph Geevarghese of Our Revolution, The Hip Hop Caucus' Rev. Lennox Yearwood, Jamie Minden of Zero Hour, and

Joseph Geevarghese of Our Revolution, The Hip Hop Caucus' Rev. Lennox Yearwood, Jamie Minden of Zero Hour, and  One Fair Wage co-founder and president Saru Jayaraman during a speech at The Gathering. (Photo: Will Allen / via The Sanders Institute)

One Fair Wage co-founder and president Saru Jayaraman during a speech at The Gathering. (Photo: Will Allen / via The Sanders Institute) Sierra Club executive director Ben Jealous, filmmaker Josh Fox, and The Sanders Institute's Dave Driscoll listen to a presentation during the Gathering in Burlington, Vermont on Saturday, June 1, 2024. (Photo: Will Allen / via The Sanders Institute)

Sierra Club executive director Ben Jealous, filmmaker Josh Fox, and The Sanders Institute's Dave Driscoll listen to a presentation during the Gathering in Burlington, Vermont on Saturday, June 1, 2024. (Photo: Will Allen / via The Sanders Institute)