SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

The paralysis of the United Nations Security Council in the face of the ongoing carnage worldwide is proof that we must rethink the existing structures of global governance.

The world is in turmoil, and there is a stark absence of strategic and moral leadership on the global stage. Indeed, there are three types of wars going on simultaneously in the world today.

The first is the proxy war between Russia and the countries of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), with Ukraine as the battlefield. The second is the trade war between the United States of America and China—with punitive tariffs, unilateral trade restrictions, covert operations in the Taiwan Straits, and protectionist maneuvers used as the tools of war.

The third, of course, is the hot war in the Middle East between Israel, Palestine, Iran, and other regional actors.

In Africa, beneath the gloss of "liberal democracy," we have seen the resurgence of totalitarian regimes and tribal demagogues, riding to political power on the coat tails of identity politics and electoral fraud.

In Sudan, to take one example, the tussle for illicit power between the country’s military and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) has displaced millions of people.

A world where “might is right,” and diplomacy is seen as a flag of surrender, results in a chaotic, barbarous, and an incredibly unhappy place to live in—for everyone.

The question asked around the world is: for how long will the United Nations—the global body formed to foster diplomacy between nations and prevent war—watch in helpless horror as cluster bombs and other deadly munitions rain down on innocent men, women, and children in these theaters of war?

The paralysis of the United Nations Security Council in the face of the ongoing carnage worldwide is proof that we must rethink the existing structures of global governance.

Everywhere in the world—in university classrooms, foreign policy think-tank sessions, media editorials and podcasts, even on the floor of the UN General Assembly—there are animated conversations about the need for a new paradigm in international relations, and what the features of the new epoch might be.

The ongoing protests in college campuses in the United States against the carnage in the Gaza Strip, in Palestine, are part of a growing global argument for a new global order. I joined this debate at Harvard Kennedy School in the fall of 2022, during our Senior Executive Fellows dinner sessions on the state of global governance in the 21st Century. The conversations were led by Secretary Ash Carter, former Defence Secretary of the United States, and Joseph Nye, a Distinguished Service Professor at Harvard Kennedy School. Joseph Nye is often rated as the most influential scholar in American foreign policy. My suggestions on the re-framing of international relations are along the lines of what I might call "Peaceful multilateralism.”

Simply put, peaceful multilateralism refers to the ability and willingness of sovereign nations to work together to solve the toughest challenges facing humanity, such as global hunger, pandemics, nuclear non-proliferation, global child trafficking and war.

Rather than the vicious zero-sum rivalry between nations, peaceful multilateralism challenges countries of the world to collaborate and work towards extending the frontiers of peace, security, and the creation of a more just world.

The notion of collaboration or cooperation between nations of the world is hardly new. After the first and second world wars, the nations of the world came together to form the United Nations Organization in 1945.

Article 1 of the Charter of the United Nations upholds the need for collaboration between nations. The Article states that one of the founding principles of the United Nations was “To achieve international co-operation in solving international problems of an economic, social, cultural, or humanitarian character, and in promoting and encouraging respect for human rights and for fundamental freedoms for all without distinction as to race, sex, language, or religion...”

However, 79 years after its founding, the United Nations appears to be at a crossroads, with nuclear-armed countries locked in a proxy war in the heart of Europe.

Below are three ways to achieve peaceful multilateralism through structural reform of the United Nations and respect for international law by all nations of the world.

1. Democratize Decision-Making at the United Nations:

For decades, questions have been raised about the ‘tyranny’ of the United Nations Security Council, where five permanent members—namely, the United States, Russia, France, the United Kingdom, and China—wield veto powers that override the views of the rest of the 185 member states of the global body.

This arrangement is not only seen to be undemocratic, but it is believed to be a major impediment to multilateral consensus building for global problem solving by the United Nations.

The latest iteration of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and the ongoing proxy war in Ukraine have shown how the conflicting interests of veto-wielding security council members in regional wars could paralyze the Security Council and impede the conflict resolution efforts by the members of the United Nations General Assembly.

Therefore, in reforming the decision-making mechanism of the United Nations, it may be critical to roll back the veto powers of the Security Council and vest the final decision-making authority on the United Nations General Assembly. The UN General Assembly should be the bastion of peaceful multilateralism and the center of decision-making on global affairs.

2. Respect for International Law: Relations between nations may be fraught with disagreements or a clash of interests. But a resort to war or unilateral actions may degrade relations further and create a climate of lawlessness and impunity on the global scene. Peaceful multilateralism can only thrive when nations engage in dialogue, diplomacy, and respect the adjudicatory supremacy of international law.

3. Commitment to Diplomacy: Finally, in an era dominated by the rhetoric of war and a “show of force” in international relations, it may seem naive to restate the importance of diplomacy in resolving conflicts between nations.

But it is the ability to disagree, engage, re-engage, and resolve conflicts diplomatically that sets us apart as humans.

A world where “might is right,” and diplomacy is seen as a flag of surrender, results in a chaotic, barbarous, and an incredibly unhappy place to live in—for everyone.

Nations that prioritize diplomacy in their relations with other nations are more likely to collaborate to solve the most pressing problems that confront humanity.

Though Barbados is a very small country, with just 280,000 people, its peaceful multilateralism gives it a big voice. It's voting record should be a model for other nations of the world—including larger, more powerful ones.

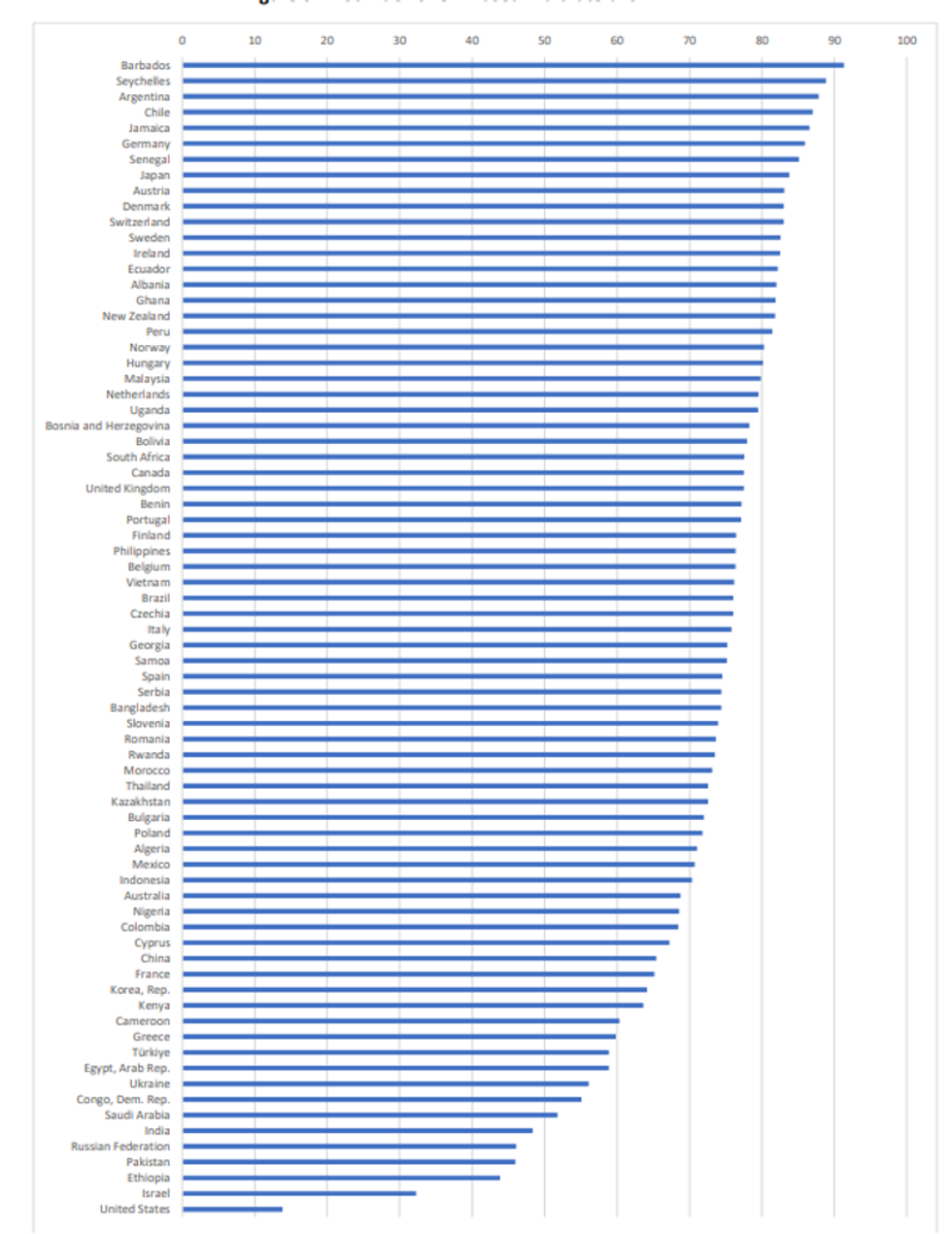

As part of our academic research on how to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), we are examining the extent to which UN member states adhere to the UN Charter and UN-backed goals such as the SDGs. Towards this end, we have created a preliminary “Multilateralism Index,” and welcome feedback and suggestions. The ranking of 74 countries according to the Multilateralism Index is shown in Figure 1 below.

Barbados ranks highest, the UN member most aligned with the UN Charter. Though Barbados is a very small country, with just 280,000 people, its peaceful multilateralism gives it a big voice. Barbados’ globally respected Prime Minister Mia Mottley, recently teamed up with French President Emmanuel Macron to co-host an important Summit for a New Global Financing Pact for People and Planet, in Paris this past June. This summit built on Barbados’ Bridgetown Initiative—named after the Barbados’ capital city—to reform the Global Financial Architecture to enable vulnerable countries cope with climate change.

At the very bottom of the ranking of 74 countries is the United States, with Israel being the second from the bottom. Both countries are frequently at odds with the UN multilateral system, as is so evident these days.

In a deeply interconnected and interdependent world, facing unprecedented and complex crises ranging from pandemics to wars to climate change, the need for multilateralism under the UN Charter is more urgent than ever.

The U.S. fails to adhere to the UN Charter in several ways. The starkest is the many wars and regime change operations that the U.S. has led, without any UN mandate and often against the will of the UN Security Council. In 2003, the U.S. tried to get the UN Security Council to vote for a war against Iraq. When the Security Council opposed the U.S., the U.S. launched the war anyway. As events later proved, the U.S. ostensible reason for launching the war, Iraq’s possession of weapons of mass destruction, did not even exist. The U.S. has engaged in dozens of covert and overt regime-change operations that violate the letter and spirit of the UN Charter. One important study finds 64 covert regime change operations by the U.S. during the Cold War, 1947-1989. There have been many well-known U.S. covert operations since then.

The U.S. also goes it alone on issues of sustainable development. In 2015, all 193 UN member states adopted the SDGs to guide national policies and international development cooperation during the period 2016-2030. Every UN member state is supposed to present its national SDG plans, challenges, and achievements to the other nations, in a presentation called the Voluntary National Review, or VNR. So far, 188 of the 193 UN member states have presented VNRs, sometimes more than once. Barbados, for instance, presented two VNRs in 2020 and 2023. Yet five countries have never presented a single VNR: Haiti, Myanmar, South Sudan, Yemen, and yes, the United States of America. South Sudan and Yemen are now on the list of countries to present a VNR in 2024, but not the US.

At this stage, the Multilateralism Index covers 74 of the 193 UN member states, the group for which we have collected extensive data on the governments’ efforts to achieve the SDGs. The Multilateralism Index is positively correlated with those SDG efforts, that is, countries abiding by UN processes (according to the Index) also demonstrate a strong commitment to the SDGs.

To be multilateral within the UN system... means to abide by UN precepts and the voice of the global community.

The Multilateralism Index is based on five indicators.

The first is the proportion of UN treaties between 1946 and 2022 that each country has ratified. As an example, Barbados has ratified more than 80 percent of major UN treaties, while the U.S. has ratified less than 60 percent.

The second is each country’s deployment of unilateral economic sanctions (sometimes called “unilateral coercive measures”) not approved by the UN. The UN General Assembly proclaimed in 1974 that “no State may use or encourage the use of economic, political or any other type of measures to coerce another State in order to obtain from it the subordination of the exercise of its sovereign rights.”

The third measures each country’s membership in major UN organizations.

The fourth measures each country’s militarization and inclination to resort to war. The indicator draws on the excellent work of the Global Peace Index.

The fifth measures each high-income country’s economic solidarity with poorer nations, according to its Official Development Assistance (ODA) as a percent of the Gross National Income (GNI). According to a resolution of the UN General Assembly in October 1970, high-income countries are supposed to devote at least 0.7 percent of GNI to ODA. The U.S., by contrast, devoted just 0.22 percent in 2022.

We combine these five indicators to produce the Multilateralism Index.

Our index, which is based on data up through 2022, has shown its predictive power. In recent weeks, in vote after vote, we have witnessed America’s self-isolation within the UN. To be multilateral within the UN system, after all, means to abide by UN precepts and the voice of the global community.

On October 18, the U.S. stood alone in the UN Security Council, when it deployed its veto to stop a resolution calling for a humanitarian ceasefire in Gaza. The vote was 12 voting yes, 2 abstentions, and the U.S. alone vetoing the measure.

Similarly, on November 2, 2023 the UN General Assembly adopted Resolution A/78/L.5, which calls on the United States to end its long-standing economic, financial, and commercial embargo on Cuba. To put it mildly, this was not a close vote: 187 countries voted in favor of the resolution, while only the United States and Israel voted against. Ukraine abstained, and three countries did not vote. Thus, the vote was 187 saying yes, 2 no, and 1 abstention. This year’s resolution follows 30 similar resolutions, dating back to 1993. The United States has ignored every single one of those UN General Assembly resolutions.

In a deeply interconnected and interdependent world, facing unprecedented and complex crises ranging from pandemics to wars to climate change, the need for multilateralism under the UN Charter is more urgent than ever. No government can do it alone. Barbados sets the highest standard for others to achieve. The U.S. needs to recognize that the UN system, operating under the UN Charter, is the true “rule-based international order.”