SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

"When American history starts getting treated like something you can ban, erase, rename, or rebrand for somebody else's ego, I can’t stand on that stage and sleep right at night," said folk singer Kristy Lee.

President Donald Trump's decision to slap his name on the side of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts is not going over well with many of the artists scheduled to perform there.

Days after the annual Kennedy Center Christmas Eve jazz concert was canceled over performers' objections to the name change, more artists have decided to withdraw in protest over the president's actions, leading to the cancelation of New Year's Eve festivities at the center.

A Monday report from the Washington Post quoted saxophonist Billy Harper, a member of the jazz ensemble the Cookers that had been set to perform on New Year's Eve, as saying his group did not want to play in a venue that had been unofficially renamed after the current president.

"I would never even consider performing in a venue bearing a name... that represents overt racism and deliberate destruction of African American music and culture," said Harper. "After all the years I spent working with some of the greatest heroes of the anti-racism fight like Max Roach and Randy Weston and Rahsaan Roland Kirk and Stanley Cowell, I know they would be turning in their graves to see me stand on a stage under such circumstances and betray all we fought for, and sacrificed for."

The Cookers weren't the only artists to withdraw from a scheduled performance at the Kennedy Center, as the New York-based dance company Doug Varone and Dancers also announced Monday that they were withdrawing from April performances at the venue.

In a social media post announcing the cancelation, the company explicitly linked its decision to Trump's renaming of the building.

"With the latest act of Donald J. Trump renaming the Center after himself, we can no longer permit ourselves nor ask our audiences to step inside this once great institution," the company explained.

Doug Varone, the head of the company, told the New York Times that his decision to cancel the performance was "financially devastating but morally exhilarating," and he noted that the troupe was set to take a $40,000 hit from withdrawing.

Folk singer Kristy Lee last week also announced she would not be performing at a scheduled Kennedy Center show in January, even while acknowledging that doing so "hurts" her financially.

However, she emphasized that "losing my integrity would cost me more than any paycheck," and argued that "when American history starts getting treated like something you can ban, erase, rename, or rebrand for somebody else's ego, I can’t stand on that stage and sleep right at night."

Trump-appointed Kennedy Center chairman Richard Grenell has lashed out bitterly at artists for canceling their performances, and accused them of having "a form of derangement syndrome." Grenell has also threatened to sue the jazz musicians who withdrew from the Christmas Eve performance for $1 million in damages.

Do not pretend to be anything other than yourself attempting to gain the approval of heartless authority and petty tyrants of the everyday kind.

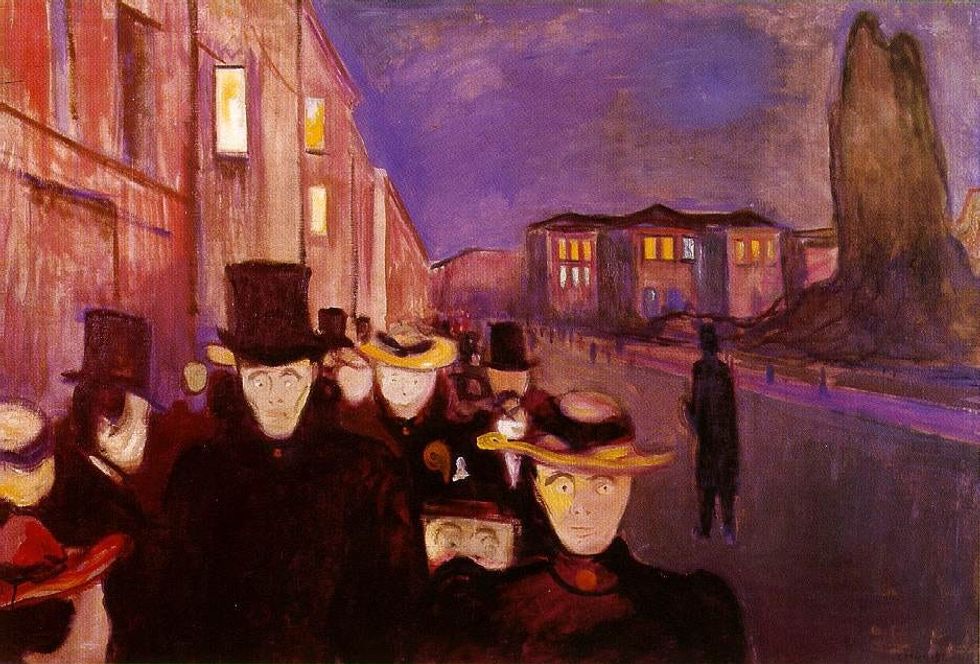

"I need to be alone. I need to ponder my shame and my despair in seclusion; I need the sunshine and the paving stones of the streets without companions, without conversation, face to face with myself, with only the music of my heart for company."—Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer

Deep down, we struggle to come upon accurate words to describe the terrible beauty of our aloneness. In this plight, we are together. In this musing, I, listening to the music of my heart, will attempt to hobble through and send back dispatches conveying a lexicon of aloneness.

A lesson I hope to learn by scribing a travelog of the dark: I've noticed, people who have survived the howling abyss of abandonment, and have been freed from its grip of grief, have been transfigured by the ordeal. Rarely, as a consequence, do such individuals act as errand boys, muscle, or apologists of oppressors.

They have snatched this from the mouth of despair, it would be tragic to be false to the forces that formed them. Thus make a vow to self: Do not pretend to be anything other than yourself attempting to gain the approval of heartless authority and petty tyrants of the everyday kind. Your wounds demand you speak your truth.

Even in our cultural atomization, we are connected to those cast out; we are bonded to society's denizens of the dark, to those who feel the pain of the suffering Earth; to those who the misnomer known as normalcy casts from conscious awareness; to those who capitalist functionality (i.e., crackpot realism) brutalizes, kicks to the curb, and condemns to madness and death… yet life on life's terms, confronts us with innumerable, seemingly infinite connections. Within, we mirror all things. We, unbeknownst to ourselves, communicate with all things. Not only the realm of the human but soil, ocean, storm, star, galaxy, electron…

We, moment to moment, travel the bridge between each other's heartbeats. We are connected both with what we love and what we shun. Moreover, what we cast out and shun will return as affliction. Hence, the Earth herself is unwell and she rages in floods and firestorms.

Breathe in deep, clear your throat, and make exhortations on behalf of the voiceless. If you have a gift for music, compose and play them a song, let the weary take refuge in the rest between musical notes. Display sacred vehemence toward life-defying oppressors who contrive to make the life of the many a prison by incarceration of the heart.

When the culture of a nation, intoxicated on extraverted mania inherent to Mephistophelian capitalism, disallows the visions of its denizens of despair into the conversation, compensatory angels borne from the unconscious (what people in times past knew as the soul) will descend bringing on a cultural darkness. In the sterile, clinical language of our time, the phenomenon is termed a pandemic of depression.

Emissaries, invisible in daylight glare, appear in the dreams of the scorned and forsaken; the visitors whisper verse to those capable of stillness, and guide the willing into moments of inadvertent reprieve. In short, deliverance occurs by means of easing the burden of self—which is a gentle way of saying, aiding one in getting the living hell over oneself. These emissaries impart the message the visible world can be a mirage. Hope is an invisible force allied with luminous angels whose light would blind us upon sight. Hence, we are moved to transformation by a force not perceptible during quotidian day.

Paradoxically, because all things arrive freighted with their opposite (enantiodromia) bearers of hope are, often, those aforementioned lonely, despair-wracked individuals driven to stand at the edge of the abyss—the abjectly lonely who have been moved, by desperation, to implore the unseen for mercy.

No person wants to arrive at such a place. One would choose, and most do, a mundane life wherein we follow the signposts, on an exclusive basis, of the visible world—yet is, in essence, given our human proclivity for habitual self-reference, a graceless tour of a house of mirrors. Oh—the hellish mix of confusion and blandness of the choice.

Prayer before sleep: Lord of nightmares bestow grace on me by allowing me to be reborn from within the womb of night. Despair's blackness grants the intrepid traveller the ability to navigate darkness, thereby avoiding a life defined by the limbo of complacency.

A person open to being ministered to, thus transformed, by a numinous voice, calling from the darkness at the edge of the daylight world, will, in all likelihood, spend their days alone, all too often suffering the pain of wounds inflicted by rejection. Loneliness will be a constant companion.

But as Rilke avers in verse:

You, darkness, that I come from

I love you more than all the fires

that fence in the world,

for the fire makes a circle of light for everyone

and then no one outside learns of you.

But the darkness pulls in everything—

shapes and fires, animals and myself,

how easily it gathers them!—

powers and people—

and it is possible a great presence is moving near me.

I have faith in nights.—Rainer Maria Rilke, "You Darkness"

Often, a shunned soul, one who travelled through the world of mindless consensus' inferno of fuckwit and has returned, will be put on the defensive by normalcy's bullies and challenged to make an accounting of himself—i.e., to account for the unaccountable. In the end, one who has seen and survived one's own darkness, will be able to apprehend the darkness within his inquisitors. At the speed of a synapse, his tormentors will go from bullying to claiming victimization.

For, when backed against the wall, he is often moved to speak in a soul-plangent lexicon that causes a collapse, even for an instant, of his tormentor's protective yet ad hoc walls of coping—thus revealing the fragile banality that governs their lives. In so doing, he has committed an act, in nice society, that will never be forgiven.

Rilke surveys the scene and sends back this dispatch in verse:

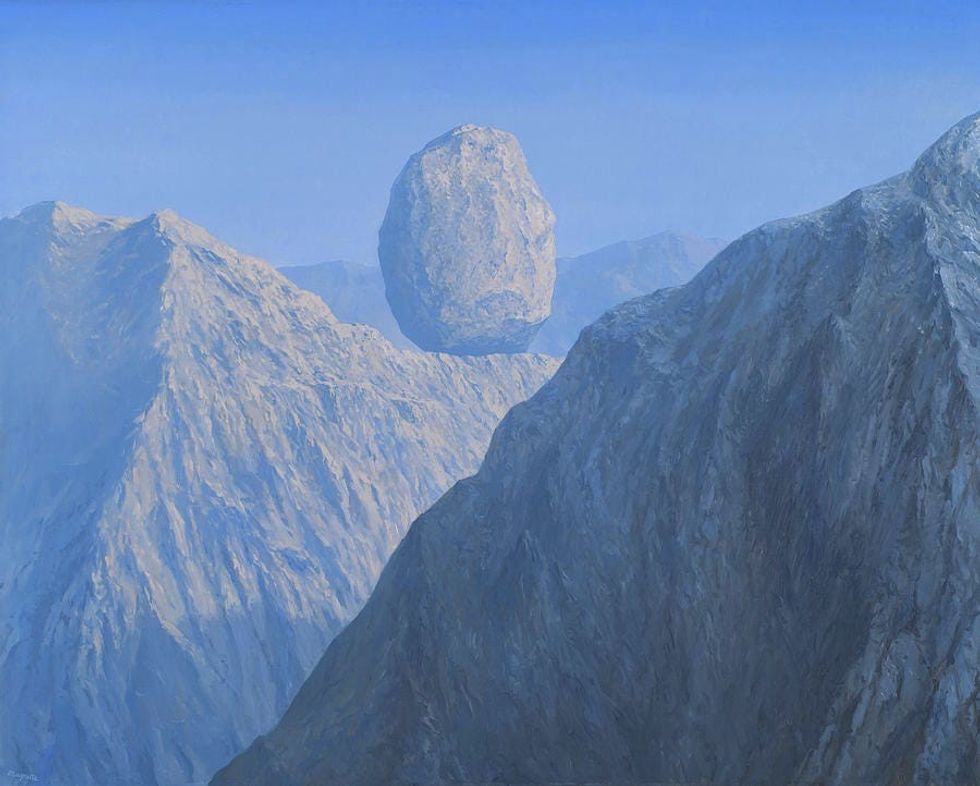

Exposed on the cliffs of the heart. Look, how tiny down there,

look: the last village of words and, higher,

(but how tiny) still one last

farmhouse of feeling. Can you see it?

Exposed on the cliffs of the heart. Stoneground

under your hands. Even here, though,

something can bloom; on a silent cliff-edge

an unknowing plant blooms, singing, into the air.

But the one who knows? Ah, he began to know

and is quiet now, exposed on the cliffs of the heart.

While, with their full awareness,

many sure-footed mountain animals pass

or linger. And the great sheltered birds flies, slowly

circling, around the peak's pure denial.—But

without a shelter, here on the cliffs of the heart.—Rilke, "Exposed On The Mountains Of My Heart"

Stop for a moment and take it all in. This life… on our Earth. The beauty. The terror. Notice: The terror involved in taking in the beauty of it all. The act will awaken your heart. Ask yourself: Am I on my heart's path? Or does this road lead me, again and again, into the dominion of exploiters? If you received an affirmative in regard to the latter question, I suggest, after you cease weeping—a sane response to you taking notice of the heart-devoid landscape where you have strayed—ask yourself: How can I reorient myself as to the direction of my heart's path?

Do you feel thwarted by circumstance, by the inherent miseries in facing capitalist hierarchies of immovable power and the system's architecture of exploitation? Rebel by engagement with the eternity delivery system of the imagination. Doing so does not translate into idle fantasy. By a receptivity to originality, by being moved to enthusiasm by acts of creativity… will provide the libido to trundle through the living landscape of imagination; thereby, one does not need to be an artist to live and engage the world in an artful manner.

Become a one person hallelujah chorus for originality. Within you, glide wheels of fire. The valley of bones rises as an army of flesh. This is your exodus out of bondage.

Just as church hymns carried our ancestors through hardships, our music today carries forward the spirit of every Black, queer person who dared to dream of visibility and freedom.

Music has always been at the very heartbeat of Black culture. Through harmonies, we have found community. Through lyrics, we have found healing. Through dance, we have found freedom in our bodies. And through the drumbeat of music, we have found resistance.

From the spirituals sung by our ancestors on the very land I stand today, to the hymns sweetly sung in my childhood church, to the bass-rattling house music in gay clubs throughout Houston, music has always connected me to my culture. And suddenly, as things begin to feel more quiet on a national stage, I am reminded that the music of Black and queer voices must keep playing, louder than ever before.

I discovered this month that Black History Month quietly vanished from my Google Calendar. Pride was gone too—a so-called “small” omission that represents something much larger and more sinister. This quiet erasure of history is becoming commonplace in public and private spaces, and it speaks volumes. With the cancellation of the Gay Men’s Chorus at the Kennedy Center, the oppressive tides of “Don’t Say Gay” legislation, the transphobic rhetoric, the defunding of LGBTQ+ healthcare and art, and the anti-DEI movements trying their hardest to erase Black and queer identities, making noise remains an act of rebellion.

Black, queer music cannot be ignored or sanitized or whitewashed or undervalued for the next four years, which means Black, queer creators need to be paid, be on the main stages, be given the mic at the awards ceremonies, and be given their flowers for the culture they sustain.

But the history of Black music cannot be rewritten to fit dominant narratives because it is the history of resistance itself. Church hymns and spirituals carried prayers and codes for the enslaved. Blues gave us a place to voice the injustices we endured. Jazz was birthed from the need for freedom of expression. Hip-hop became our weapon to challenge our oppressors. And our many contributions—too often uncredited—built the foundation for rock, country, pop, house, dance, and so much more.

And queer artists have been pivotal to this story. Billy Strayhorn, Duke Ellington’s openly gay composer, brought undeniable brilliance to the jazz world. Billie Holiday turned her voice into a protest. Little Richard, known fondly as the “King of Rock and Roll,” shattered norms and sang about his desires with the kind of joy that felt revolutionary. Sylvester, the “Queen of Disco,” gave us revolutionary anthems of love and resilience while fighting on the frontlines of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Gospel music would cease to exist if the Black, queer writers, singers, and composers were erased.

Even today, Black LGBTQ+ artists are breaking records and capturing the world’s attention. Big Freedia is the New Orleans “Queen of Bounce” whose music and style have been sampled by some of the biggest artists today. Lil Nas X is bending genres and expectations for Black male rappers. Doechii captivated everyone watching this year’s Grammys and used her speech as a message of hope for Black and queer creators. These artists are showing that the power of being visible and unrelenting in their truth extends far beyond music charts.

But here’s the truth we can’t ignore—many of the icons that came before them, or are their peers today, still have to hide who they were and are. Societal pressures and safety concerns force them into invisibility. And now fear remains that if billion-dollar industries are cowering to current political climates, what will that mean for Black, queer creators?

That is why it is so important to support Black and queer creators, through hiring, funding, streaming, and screaming their songs at the top of our lungs. Their music doesn’t just entertain; it liberates. It mends spirits and moves people to think, to feel, and to act. It’s an instrument of resistance and a tool to drown out this world’s hate. Black, queer music cannot be ignored or sanitized or whitewashed or undervalued for the next four years, which means Black, queer creators need to be paid, be on the main stages, be given the mic at the awards ceremonies, and be given their flowers for the culture they sustain.

When The Normal Anomaly started BQAF (Black Queer AF) Music Festival in Houston, Texas four years ago, it was not created to be a demonstration. We just believed the power of music could bring people together, and—since no one in Texas had done it before—to center it around Black, queer, and allied artists we loved seemed logical. Now, it is the track list to a freedom song so necessary to repeat to quiet the deafening sounds of hate and fear for the community.

That’s why we’re unapologetically taking up space and taking the stage at this year’s BQAF Music Festival, an all-Black queer and allied lineup. For our fourth iteration, our theme this year is VISIBILITY. This music festival is a love letter to our community and our message to the nation and the world—we won’t be erased or silenced. We will be seen, heard, felt, and celebrated. We are turning the volume all the way up—not just for Houston to hear, but for every person across this country who has been made to feel like their identity does not deserve respect or recognition.

We’ve built momentum as a community. Black, queer artists are out here breaking records, genres, and boundaries. And we will not halt this progress. Just as church hymns carried our ancestors through hardships, our music today carries forward the spirit of every Black, queer person who dared to dream of visibility and freedom. Together, we’ll send a message to every lawmaker and system working against us. They may try to silence us, but Black and queer music will always be louder.

As long as there is air in my lungs, I will have a song to sing that fills the silence with the beauty, resilience, and limitless brilliance of our culture.