The actors’ strike began on July 14, 2023, after their union, SAG-AFTRA, voted to end negotiations with the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers, which represents the major production studios. The main concerns of the union—which represents 160,000 actors and people in other creative professions—center around compensation on streaming platforms, such as Netflix and Amazon Prime, and artificial intelligence.

Screenwriters, who have been on strike since May 2, have similar concerns.

In 1965, executives made 15 times the average salary of their workers. By 2021 those top execs were earning 350 times more than the average worker—including actors.Screenwriters, who have been on strike since May 2, have similar concerns.

The two strikes have halted U.S. TV and movie production. Premieres are being canceled, and Emmy-nominated actors aren’t campaigning for those prestigious TV awards.

Rewind to the Rise of TV

Charlton Heston (R) and then-Screen Actors Guild President Ronald Reagan shake hands with members of the Association of Motion Picture Producers after SAG ended its 1960 strike.

(Photo: Getty Images)

Ever since Louis Le Prince filmed the first movie, Roundhay Garden Scene, in 1888, actors have earned a living through their work being shown on screens small and large.

The first hit shows on TV aired in the mid-1940s, but actors initially earned far less from television than movies. Around 1960, with the advent of hits like Leave It to Beaver, Beverly Hillbillies, and Bonanza, TV became very profitable. TV’s growing prestige and economic heft gave television actors newfound power at the contract negotiating table.

Actors demanded that their craft be compensated for TV shows about as highly as for their film appearances. Led by future President Ronald Reagan and Charlton Heston—who went on to serve as a National Rifle Association president—the Screen Actors Guild went on strike on March 7, 1960. Among that union’s top demands: health care coverage and residuals for movies aired on television, reruns, and syndication.

Hwang Dong-hyuk, the creator of Squid Game, forfeited all residuals when he cut a deal with Netflix. It earned Netflix nearly US$1 billion, but Hwang got none of that bounty.

Residuals are a form of royalty paid to actors when movies and TV shows air on television after their initial run. That can include reruns, syndication, and the broadcasting of movies on television.

The actors union’s strike, which coincided then as today with a screenwriters strike, successfully negotiated a contract with executives that resolved the residuals conflict and secured health care coverage for its members.

That contract applied to broadcasting and, years later, cable TV.

But it doesn’t work for streaming, because streamed shows aren’t scheduled. Whereas Friends, a sitcom that initially aired on NBC, is available today on Max, formerly HBO Max, through syndication, and its actors receive relevant residuals, Orange Is the New Black originated on Netflix. Because it never runs on a different platform via syndication, the actors in its cast earn paltry residuals in comparison—even though viewers are still watching the show’s seven seasons.

Hwang Dong-hyuk, the creator of Squid Game, forfeited all residuals when he cut a deal with Netflix. It earned Netflix nearly US$1 billion, but Hwang got none of that bounty.

Fast-Forward to 2023

As I explained in my 2021 book, Streaming Culture, streaming has fundamentally changed the production and consumption of both TV and film while blurring the lines between them.

People consume different types of media through subscriptions and streaming technology than they do while watching broadcast TV and cable television. Actors and writers are concerned that their compensation hasn’t kept up with this transformation.

And the actors who are on strike argue that the formulas in place since 1960 to calculate residuals don’t work anymore.

In contrast, streaming residuals pay a flat rate for foreign and domestic streams.

Residuals paid for roles in broadcast TV shows are based on the popularity of those programs, with actors earning far more for hits like Grey’s Anatomy and NCIS than for duds. Hit shows can have a second life on streaming platforms and result in actors getting paid again for that earlier work.

In contrast, streaming residuals pay a flat rate for foreign and domestic streams. A streaming original film or TV show earns a set amount for residuals in its domestic market and second set amount for foreign markets. This fee doesn’t change based on popularity or the number of times a production is streamed.

But streaming has changed more than residuals for actors and writers. It has also transformed how TV shows are made.

Ejecting Regularly Scheduled Shows

Many TV seasons have grown shorter since streaming became the norm, falling from 20 or more episodes to 10 or fewer per season.

That’s because streamers started making shows with lower budgets, as it costs less to produce fewer episodes. The studios also cut costs by hiring fewer writers.

Since actors are typically paid per episode in which they perform, their salaries have dropped by virtue of having fewer appearances in even the most popular shows.

As gaps between seasons grow, some actors are having a harder and harder time making ends meet.

The gaps between seasons have also grown longer and more unpredictable. Every season of the nine-year run of Seinfeld on NBC began in the fall and ended the next spring, then picked up again the next fall.

Streaming shows are far less predictable.

Amazon Prime’s The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel paused for more than two years between seasons 3 and 4.

The same streamer aired the first season of Lord of the Rings: Power of the Rings, in September 2022, but Season 2 won’t be released until late 2024.

As gaps between seasons grow, some actors are having a harder and harder time making ends meet.

Another change has to do with the question of whether particular shows will keep going. In conventional broadcast or cable television, networks determine whether they will renew a show during the period known as “sweeps,” at the end of a TV season. Since streaming television has no defined seasons, these decisions can drag on.

This can leave actors and writers in limbo. And their contracts often stop them from working on other shows between seasons.

Will AI Erase Actors?

SAG-AFTRA President Fran Drescher joins Writers Guild members at a picket line outside of Warner Bros studio in Burbank, California, on July 14, 2023.

(Photo: Valerie Macon/AFP via Getty Images)

Although residuals and the number of episodes have until now been negotiable, perhaps the strike’s biggest issue is the studios’ use of artificial intelligence

Actors fear studios will use AI to replace actors in the future. Without a contract that says otherwise, once a studio films an actor, it can potentially use the actor’s likeness in perpetuity. This means a background actor could be shot for one episode of a TV show and continue to be seen in the background for seasons without pay.

That hasn’t happened yet, but many actors are certain it will.

As Drescher continually points out in her media appearances, 99% of actors are struggling on working-class incomes.

Actors object to the possibility that studios will seek to “own our likeness in perpetuity, including after we’re dead, use us in their movies without any consent, without any compensation to our performers, especially background performers,” said actor Shaan Sharma, best known for his role on The Chosen. “It’s inhumane. It is dystopian.”

Until now, actors and writers say, the studios have refused to negotiate over AI with actors or writers. But both unions see AI as a threat to their members’ livelihoods, a point SAG-AFTRA President Fran Drescher made on MSNBC.

As Drescher continually points out in her media appearances, 99% of actors are struggling on working-class incomes. Meanwhile, studio executives continue to increase their own pay. For example, in 2022, Netflix co-CEOs Reed Hastings and Ted Sarandos earned roughly $50 million each. Warner-Discovery CEO David Zaslav earned $39 million.

No ‘Pause’ for Widening Inequality Gap

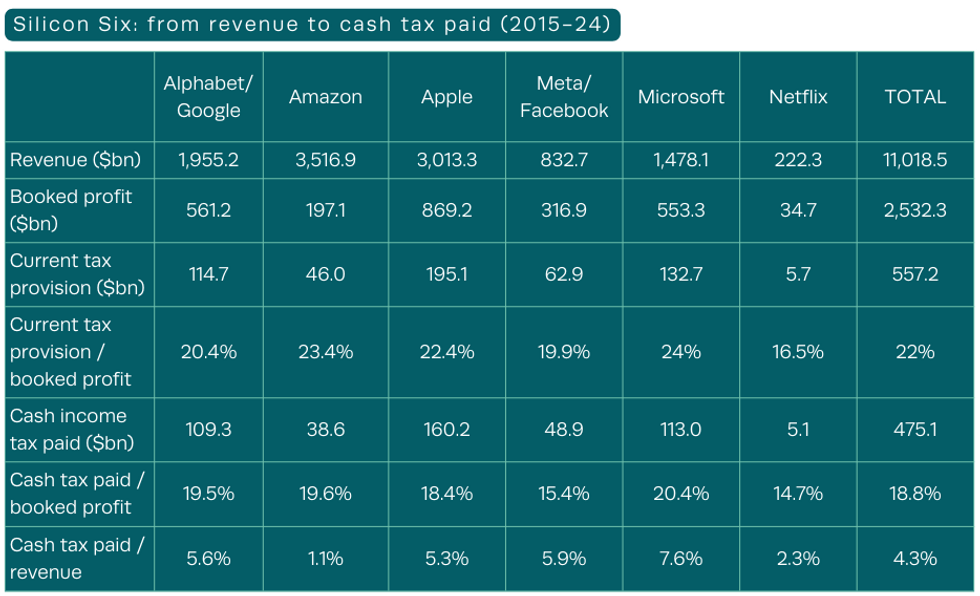

The gulf between what actors and top executives earn is a major difference between today’s actors and writer strikes and the 1960 strikes. In 1965, executives made 15 times the average salary of their workers. By 2021 those top execs were earning 350 times more than the average worker—including actors.

And while today’s biggest stars, like Pedro Pascal and Natasha Lyonne, earn millions for every performance, most actors struggle to make ends meet.

In Los Angeles, actors earn an average hourly wage of $27.73.

Meanwhile, studios are pulling in huge profits. For example, Netflix and Warner Bros. earned $5.2 billion and $2.7 billion in 2022, respectively.

Watching Union Action on Repeat

As I explain in my new book, Digital Feudalism: Creators, Credit, Consumption, and Capitalism, striking actors and screenwriters are part of the wave of labor unrest in recent years. In my view, U.S. workers are rejecting a system that expects workers to buy more on credit while making a living with increasingly precarious jobs.

From Starbucks baristas to Amazon’s union organizers to the workers planning the pending UPS strike, more and more Americans are fighting for higher wages and more control over their schedules.

In fighting threats to their livelihoods, actors and screenwriters are the latest example of a national movement for stronger labor rights.