What Are SMRs?

SMRs are nuclear reactors that are “small” (defined as 300 megawatts of electrical power or less), can be largely assembled in a centralized facility, and would be installed in a modular fashion at power generation sites. Some proposed SMRs are so tiny (20 megawatts or less) that they are called “micro” reactors. SMRs are distinct from today’s conventional nuclear plants, which are typically around 1,000 megawatts and were largely custom-built. Some SMR designs, such as NuScale, are modified versions of operating water-cooled reactors, while others are radically different designs that use coolants other than water, such as liquid sodium, helium gas, or even molten salts.

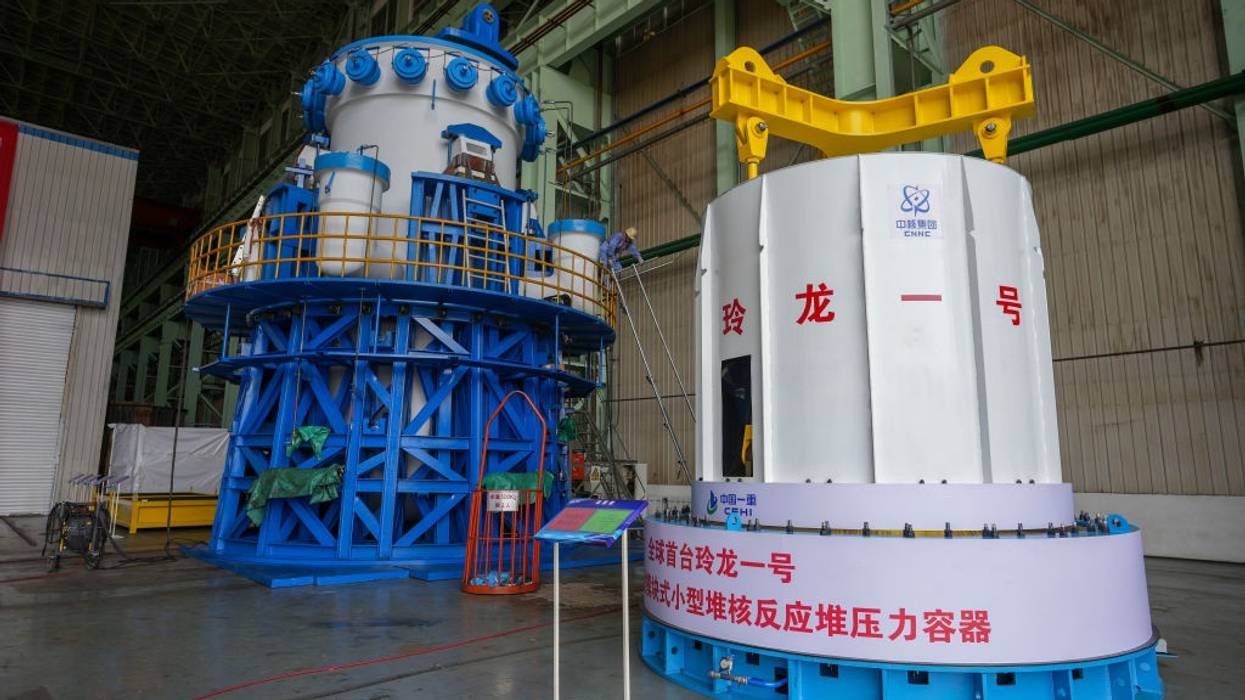

To date, however, theoretical interest in SMRs has not translated into many actual reactor orders. The only SMR currently under construction is in China. And in the United States, only one company—TerraPower, founded by Microsoft’s Bill Gates—has applied to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) for a permit to build a power reactor (but at 345 megawatts, it technically isn’t even an SMR).

The nuclear industry has pinned its hopes on SMRs primarily because some recent large reactor projects, including Vogtle units 3 and 4 in the state of Georgia, have taken far longer to build and cost far more than originally projected. The failure of these projects to come in on time and under budget undermines arguments that modern nuclear power plants can overcome the problems that have plagued the nuclear industry in the past.

Regulators are loosening safety and security requirements for SMRs in ways which could cancel out any safety benefits from passive features.

Developers in the industry and the U.S. Department of Energy say that SMRs can be less costly and quicker to build than large reactors and that their modular nature makes it easier to balance power supply and demand. They also argue that reactors in a variety of sizes would be useful for a range of applications beyond grid-scale electrical power, including providing process heat to industrial plants and power to data centers, cryptocurrency mining operations, petrochemical production, and even electrical vehicle charging stations.

Here are five facts about SMRs that the nuclear industry and the “nuclear bros” who push its message don’t want you, the public, to know.

1. SMRs Are Not More Economical Than Large Reactors.

In theory, small reactors should have lower capital costs and construction times than large reactors of similar design so that utilities (or other users) can get financing more cheaply and deploy them more flexibly. But that doesn’t mean small reactors will be more economical than large ones. In fact, the opposite usually will be true. What matters more when comparing the economics of different power sources is the cost to produce a kilowatt-hour of electricity, and that depends on the capital cost per kilowatt of generating capacity, as well as the costs of operations, maintenance, fuel, and other factors.

According to the economies of scale principle, smaller reactors will in general produce more expensive electricity than larger ones. For example, the now-cancelled project by NuScale to build a 460-megawatt, 6-unit SMR in Idaho was estimated to cost over $20,000 per kilowatt, which is greater than the actual cost of the Vogtle large reactor project of over $15,000 per kilowatt. This cost penalty can be offset only by radical changes in the way reactors are designed, built, and operated.

For example, SMR developers claim they can slash capital cost per kilowatt by achieving efficiency through the mass production of identical units in factories. However, studies find that such cost reductions typically would not exceed about 30%. In addition, dozens of units would have to be produced before manufacturers could learn how to make their processes more efficient and achieve those capital cost reductions, meaning that the first reactors of a given design will be unavoidably expensive and will require large government or ratepayer subsidies to get built. Getting past this obstacle has proven to be one of the main impediments to SMR deployment.

The levelized cost of electricity for the now-cancelled NuScale project was estimated at around $119 per megawatt-hour (without federal subsidies), whereas land-based wind and utility-scale solar now cost below $40/MWh.

Another way that SMR developers try to reduce capital cost is by reducing or eliminating many of the safety features required for operating reactors that provide multiple layers of protection, such as a robust, reinforced concrete containment structure, motor-driven emergency pumps, and rigorous quality assurance standards for backup safety equipment such as power supplies. But these changes so far haven’t had much of an impact on the overall cost—just look at NuScale.

In addition to capital cost, operation and maintenance (O&M) costs will also have to be significantly reduced to improve the competitiveness of SMRs. However, some operating expenses, such as the security needed to protect against terrorist attacks, would not normally be sensitive to reactor size. The relative contribution of O&M and fuel costs to the price per megawatt-hour varies a lot among designs and project details, but could be 50% or more, depending on factors such as interest rates that influence the total capital cost.

Economies of scale considerations have already led some SMR vendors, such as NuScale and Holtec, to roughly double module sizes from their original designs. The Oklo, Inc. Aurora microreactor has increased from 1.5 MW to 15 MW and may even go to 50 MW. And the General Electric-Hitachi BWRX-300 and Westinghouse AP300 are both starting out at the upper limit of what is considered an SMR.

Overall, these changes might be sufficient to make some SMRs cost-competitive with large reactors, but they would still have a long way to go to compete with renewable technologies. The levelized cost of electricity for the now-cancelled NuScale project was estimated at around $119 per megawatt-hour (without federal subsidies), whereas land-based wind and utility-scale solar now cost below $40/MWh.

Microreactors, however, are likely to remain expensive under any realistic scenario, with projected levelized electricity costs two to three times that of larger SMRs.

2. SMRs Are Not Generally Safer or More Secure Than Large Light-Water Reactors.

Because of their size, you might think that small nuclear reactors pose lower risks to public health and the environment than large reactors. After all, the amount of radioactive material in the core and available to be released in an accident is smaller. And smaller reactors produce heat at lower rates than large reactors, which could make them easier to cool during an accident, perhaps even by passive means—that is, without the need for electrically powered coolant pumps or operator actions.

However, the so-called passive safety features that SMR proponents like to cite may not always work, especially during extreme events such as large earthquakes, major flooding, or wildfires that can degrade the environmental conditions under which they are designed to operate. And in some cases, passive features can actually make accidents worse: For example, the NRC’s review of the NuScale design revealed that passive emergency systems could deplete cooling water of boron, which is needed to keep the reactor safely shut down after an accident.

In any event, regulators are loosening safety and security requirements for SMRs in ways which could cancel out any safety benefits from passive features. For example, the NRC has approved rules and procedures in recent years that provide regulatory pathways for exempting new reactors, including SMRs, from many of the protective measures that it requires for operating plants, such as a physical containment structure, an offsite emergency evacuation plan, and an exclusion zone that separates the plant from densely populated areas. It is also considering further changes that could allow SMRs to reduce the numbers of armed security personnel to protect them from terrorist attacks and highly trained operators to run them. Reducing security at SMRs is particularly worrisome, because even the safest reactors could effectively become dangerous radiological weapons if they are sabotaged by skilled attackers. Even passive safety mechanisms could be deliberately disabled.

Considering the cumulative impact of all these changes, SMRs could be as—or even more— dangerous than large reactors. For example, if a containment structure at a large reactor reliably prevented 90% of the radioactive material from being released from the core of the reactor during a meltdown, then a reactor five times smaller without such a containment structure could conceivably release more radioactive material into the environment, even though the total amount of material in the core would be smaller. And if the SMR were located closer to populated areas with no offsite emergency planning, more people could be exposed to dangerously high levels of radiation.

But even if one could show that the overall safety risk of a small reactor was lower than that of a large reactor, that still wouldn’t automatically imply the overall risk per unit of electricity that it generates is lower, since smaller plants generate less electricity. If an accident caused a 250-megawatt SMR to release only 25% of the radioactive material that a 1,000-megawatt plant would release, the ratio of risk to benefit would be the same. And a site with four such reactors could have four times the annual risk of a single unit, or an even greater risk if an accident at one reactor were to damage the others, as happened during the 2011 Fukushima Daiichi accident in Japan.

3. SMRs Will Not Reduce the Problem of What to Do With Radioactive Waste.

The industry makes highly misleading claims that certain SMRs will reduce the intractable problem of long-lived radioactive waste management by generating less waste, or even by “recycling” their own wastes or those generated by other reactors.

First, it’s necessary to define what “less” waste really means. In terms of the quantity of highly radioactive isotopes that result when atomic nuclei are fissioned and release energy, small reactors will produce just as much as large reactors per unit of heat generated. (Non-light-water reactors that more efficiently convert heat to electricity than light-water reactors will produce somewhat smaller quantities of fission products per unit of electricity generated—perhaps 10 to 30%—but this is a relatively small effect in the scheme of things.) And for reactors with denser fuels, the volume and mass of the spent fuel generated may be smaller, but the concentration of fission products in the spent fuel, and the heat generated by the decay products—factors that really matter to safety—will be proportionately greater.

Therefore, entities that hope to acquire SMRs, like data centers that lack the necessary waste infrastructure, will have to safely manage the storage of significant quantities of spent nuclear fuel on site for the long term, just like any other nuclear power plant does. Claims by vendors such as Westinghouse that they will take away the reactors after the fuel is no longer usable are simply not credible, as there are no realistic prospects for licensing centralized sites where the used reactors could be taken for the foreseeable future. Any community with an SMR will have to plan to be a de facto long-term nuclear waste disposal site.

4. SMRs Cannot Be Counted on to Provide Reliable and Resilient Off-the-Grid Power for Facilities, Such as Data Centers, Bitcoin Mining, Hydrogen, or Petrochemical production.

Despite the claims of developers, it is very unlikely that any reasonably foreseeable SMR design would be able to safely operate without reliable access to electricity from the grid to power coolant pumps and other vital safety systems. Just like today’s nuclear plants, SMRs will be vulnerable to extreme weather events or other disasters that could cause a loss of offsite power and force them to shut down. In such situations a user such as a data center operator would have to provide backup power, likely from diesel generators, for both the data center AND the reactor. And since there is virtually no experience with operating SMRs worldwide, it is highly doubtful that the novel designs being pitched now would be highly reliable right out of the box and require little monitoring and maintenance.

It very likely will take decades of operating experience for any new reactor design to achieve the level of reliability characteristic of the operating light-water reactor fleet. Premature deployment based on unrealistic performance expectations could prove extremely costly for any company that wants to experiment with SMRs.

5. SMRs Do Not Use Fuel More Efficiently Than Large Reactors.

Some advocates misleadingly claim that SMRs are more efficient than large ones because they use less fuel. In terms of the amount of heat generated, the amount of uranium fuel that must undergo nuclear fission is the same whether a reactor is large or small. And although reactors that use coolants other than water typically operate at higher temperatures, which can increase the efficiency of conversion of heat to electricity, this is not a big enough effect to outweigh other factors that decrease efficiency of fuel use.

Some SMRs designs require a type of uranium fuel called “high-assay low enriched uranium (HALEU),” which contains higher concentrations of the isotope uranium-235 than conventional light-water reactor fuel. Although this reduces the total mass of fuel the reactor needs, that doesn’t mean it uses less uranium nor results in less waste from “front-end” mining and milling activities: In fact, the opposite is more likely to be true.

If the nuclear bros have such a great SMR story to tell, why do they have to exaggerate so much?

One reason for this is that HALEU production requires a relatively large amount of natural uranium to be fed into the enrichment process that increases the uranium-235 concentration. For example, the TerraPower Natrium reactor which would use HALEU enriched to around 19% uranium-235, will require 2.5 to 3 times as much natural uranium to produce a kilowatt-hour of electricity than a light-water reactor. Smaller reactors, such as the 15-megawatt Oklo Aurora, are even more inefficient. Improving the efficiency of these reactors can occur only with significant advances in fuel performance, which could take decades of development to achieve.

Reactors that use uranium inefficiently have disproportionate impacts on the environment from polluting uranium mining and processing activities. They also are less effective in mitigating carbon emissions, because uranium mining and milling are relatively carbon-intensive activities compared to other parts of the uranium fuel cycle.

SMRs may have a role to play in our energy future, but only if they are sufficiently safe and secure. For that to happen, it is essential to have a realistic understanding of their costs and risks. By painting an overly rosy picture of these technologies with often misleading information, the nuclear bros are distracting attention from the need to confront the many challenges that must be resolved to make SMRs a reality—and ultimately doing a disservice to their cause.