Less discussed was Volcker's role at the behest of President Richard Nixon in taking the dollar off the gold standard, which he called "the single most important event of his career." He evidently intended for another form of stable exchange system to replace the Bretton Woods system it destroyed, but that did not happen. Instead, freeing the dollar from gold unleashed an unaccountable central banking system that went wild printing money for the benefit of private Wall Street and London financial interests.

The power to create money can be a good and necessary tool in the hands of benevolent leaders working on behalf of the people and the economy. But like with the Sorcerer's Apprentice in Disney's "Fantasia," if it falls in the wrong hands, it can wreak havoc on the world. Unfortunately for Volcker's legacy and the well-being of the rest of us, his signature policies led to the devastation of the American working class in the 1980s and ultimately set the stage for the 2008 global financial crisis.

The Official Story and Where It Breaks Down

According to a Dec. 9 obituary in The Washington Post:

Mr. Volcker's greatest historical mark was in eight years as Fed chairman. When he took the reins of the central bank, the nation was mired in a decade-long period of rapidly rising prices and weak economic growth. Mr. Volcker, overcoming the objections of many of his colleagues, raised interest rates to an unprecedented 20%, drastically reducing the supply of money and credit.

The Post acknowledges that the effect on the economy was devastating, triggering what was then the deepest economic downturn since the Depression of the 1930s, driving thousands of businesses and farms to bankruptcy and propelling the unemployment rate past 10%:

Mr. Volcker was pilloried by industry, labor unions and lawmakers of all ideological stripes. He took the abuse, convinced that this shock therapy would finally break Americans' expectations that prices would forever rise rapidly and that the result would be a stronger economy over the longer run.

On this he was right, contends the author:

Soon after Mr. Volcker took his foot off the brake of the U.S. economy in 1981, and the Fed began lowering interest rates, the nation began a quarter century of low inflation, steady growth, and rare and mild recessions. Economists attribute that period, one of the sunniest in economic history, at least in part to the newfound credibility as an inflation-fighter that Mr. Volcker earned for the Fed.

That is the conventional version, but the stagflation of the 1970s and its sharp reversal in the early 1980s appears more likely to have been due to a correspondingly sharp rise and fall in the price of oil. There is evidence this oil shortage was intentionally engineered for the purpose of restoring the global dominance of the U.S. dollar, which had dropped precipitously in international markets after it was taken off the gold standard in 1971.

The Other Side of the Story

How the inflation rate directly followed the price of oil was tracked by Benjamin Studebaker in a 2012 article titled "Stagflation: What Really Happened in the 70's":

We see that the problem begins in 1973 with the '73-'75 recession - that's when growth first dives. In October of 1973, the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries declared an oil embargo upon the supporters of Israel - western nations. The '73-'75 recession begins in November of 1973, immediately after. During normal recessions, inflation does not rise - it shrinks, as people spend less and prices fall. So why does inflation rise from '73-'75? Because this recession is not a normal recession - it is sparked by an oil shortage. The price of oil more than doubles in the space of a mere few months from '73-'74. Oil is involved in the manufacturing of plastics, in gasoline, in sneakers, it's everywhere. When the price of oil goes up, the price of most things go up. The spike in the oil price is so large that it drives up the costs of consumer goods throughout the rest of the economy so fast that wages fail to keep up with it. As a result, you get both inflation and a recession at once.

... Terrified by the double-digit inflation rate in 1974, the Federal Reserve switches gears and jacks the interest rate up to near 14%. ... The economy slips back into the throws of the recession for another year or so, and the unemployment rate takes off, rising to around 9% by 1975. ...

Then, in 1979, the economy gets another oil price shock (this time caused by the Revolution in Iran in January of that year) in which the price of oil again more than doubles. The result is a fall in growth and inflation knocked all the way up into the teens. The Federal Reserve tries to fight the oil-driven inflation by raising interest rates high into the teens, peaking out at 20% in 1980.

... [B]y 1983, the unemployment rate has peaked at nearly 11%. To fight this, the Federal Reserve knocks the interest rate back below 10%, and meanwhile, alongside all of this, Ronald Reagan spends lots of money and expands the state in '82/83. ... Why does inflation not respond by returning? Because oil prices are falling throughout this period, and by 1985 have collapsed utterly.

The federal funds rate was just below 10% in 1975 at the height of the early stagflation crisis. How could the same rate that was responsible for inflation in the 1970s drop the consumer price index to acceptable levels after 1983? And if the federal funds rate has that much effect on inflation, why is the extremely low 1.55% rate today not causing hyperinflation? What Fed Chairman Jerome Powell is now fighting instead is deflation, a lack of consumer demand causing stagnant growth in the real, producing economy.

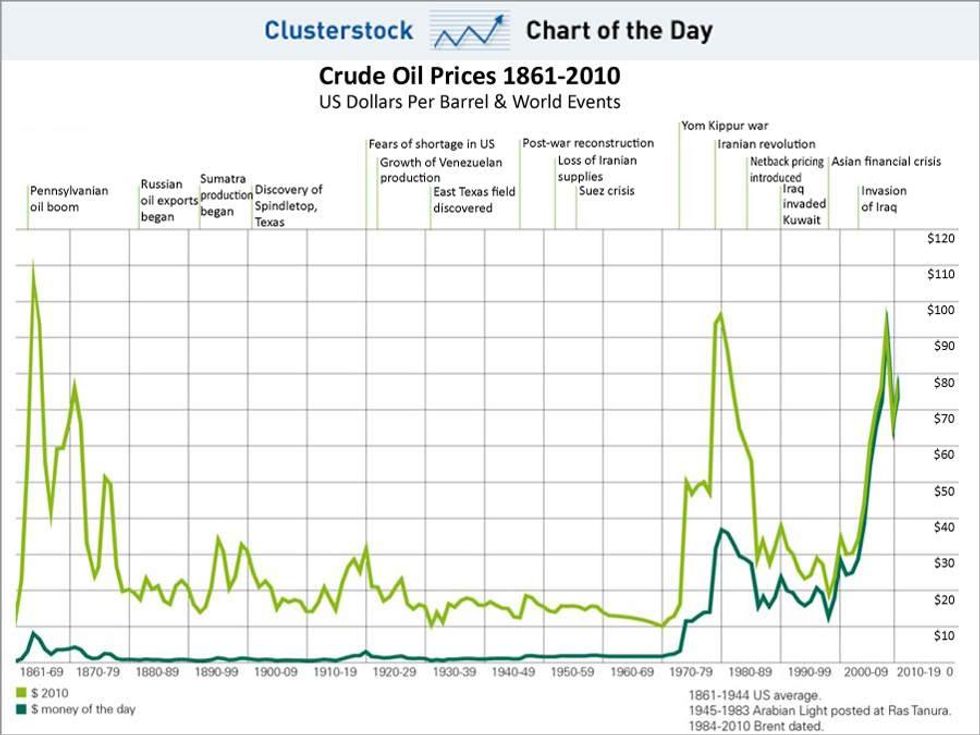

Thus it looks as if oil, not the federal funds rate, was the critical factor in the rise and fall of consumer prices in the 1970s and 1980s. "Stagflation" was just a predictable result of the shortage of this essential commodity at a time when the country was not energy-independent. The following chart from Business Insider Australia shows the historical correlations:

The Plot Thickens

But there's more. The subplot is detailed by William Engdahl in "The Gods of Money"(2009). To counter the falling dollar after it was taken off the gold standard, U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger and President Nixon held a clandestine meeting in 1972 with the Shah of Iran. Then, in 1973, a group of powerful financiers and politicians met secretly in Sweden to discuss how the dollar might effectively be "backed" by oil. An arrangement was finalized in which the oil-producing countries of OPEC would sell their oil only in U.S. dollars, and the dollars would wind up in Wall Street and London banks, where they would fund the burgeoning U.S. debt.

For the OPEC countries, the quid pro quo was military protection, along with windfall profits from a dramatic boost in oil prices. In 1974, according to plan, an oil embargo caused the price of oil to quadruple, forcing countries without sufficient dollar reserves to borrow from Wall Street and London banks to buy the oil they needed. Increased costs then drove up prices worldwide.

The story is continued by Matthieu Auzanneau in "Oil, Power, and War: A Dark History":

The panic caused by the Iranian Revolution raised a new tsunami of inflation that was violently unleashed on the world economy, whose consequences were even greater than what took place in 1973. Once again, the sharp, unexpected increase in the price of crude oil instantly affected transportation, construction, and agriculture - confirming oil's ubiquity. ... The time of draconian monetarist policies advocated by economist Milton Friedman, David Rockefeller's protege, had arrived. The Bank of England's interest rate was around 16% in 1980. The impact on the economy was brutal. ...

Appointed by President Carter in August 1979, Paul Volcker, the new chief of the Federal Reserve, administered the same shock treatment [drastically raising interest rates] to the American economy. Carter had initially offered the position to David Rockefeller; Chase Manhattan's president politely declined the offer and "strongly" recommended that Carter appeal to Volcker (who had been a Chase vice president in the 1960s). To stop the spiral of inflation that endangered the profitability and stability of all banks, the Federal Reserve increased its benchmark rate to 20% in 1980 and 1981. The following year, 1982, the American economy experienced a 2% recession, much more severe than the recession of 1974.

In an article in American Opinion in 19179, Gary Allen, author of "None Dare Call It Conspiracy: The Rockefeller Files" (1971), observed that both Volcker and Henry Kissinger were David Rockefeller proteges. Volcker had worked for Rockefeller at Chase Manhattan Bank and was a member of the Trilateral Commission and the Council on Foreign Relations. In 1971, when he was Treasury undersecretary for monetary affairs, Volcker played an instrumental role in the top-secret Camp David meeting at which the president approved taking the dollar off the gold standard. Allen wrote that it was Volcker who "led the effort to demonetize gold in favor of bookkeeping entries as part of another international banking grab. His appointment now threatens an economic bust."

Volcker's Real Legacy

Allen went on:

How important is the post to which Paul Volcker has been appointed? The New York Times tells us: "As the nation's central bank, the Federal Reserve System, which by law is independent of the Administration and Congress, has exclusive authority to control the amount of money available to consumers and businesses." ... This means that the Federal Reserve Board has life-and-death power over the economy.

And that is Paul Volcker's true legacy. At a time when the Fed's credibility was "greatly diminished," he restored to it the life-and-death power over the economy that it continues to exercise today. His "shock therapy" of the early 1980s broke the backs of labor and the unions, bankrupted the savings and loans, and laid the groundwork for the "liberalization" of the banking laws that allowed securitization, derivatives, and the repo market to take center stage. As noted by Jeff Spross in The Week, Volcker's chosen strategy essentially loaded all the pain onto the working class, an approach to monetary policy that has shaped Fed policy ever since.

In 2008-09, the Fed was an opaque accessory to the bank heist in which massive fraud was covered up and the banks were made whole despite their criminality. Taking the dollar off the gold standard allowed the Fed to engage in the "quantitative easing" that underwrote this heist. Bolstered by OPEC oil backing, uncoupling the dollar from gold also allowed it to maintain and expand its status as global reserve currency.

What was Volcker's role in all this? He is described by those who knew him as a personable man who lived modestly and didn't capitalize on his powerful position to accumulate personal wealth. He held a lifelong skepticism of financial elites and financial "innovation." He proposed a key restriction on speculative activity by banks that would become known as the "Volcker Rule." In the late 1960s, he opposed allowing global exchange rates to float freely, which he said would allow speculators to "pounce on a depreciating currency, pushing it even lower." And he evidently regretted the calamity caused by his 1980s shock treatment, saying if he could do it over again, he would do it differently.

It could be said that Volcker was a good man, who spent his life trying to rectify that defining moment when he helped free the dollar from gold. Ultimately, eliminating the gold standard was a necessary step in allowing the money supply to expand to meet the needs of trade. The power to create money can be a useful tool in the right hands. It just needs to be recaptured and wielded in the public interest, following the lead of the American colonial governments that first demonstrated its very productive potential.