The draft order takes aim at California's new AI safety laws, calling them "complex and burdensome" and claiming they are based on "purely speculative suspicion" that AI could harm users.

“States like Alabama, California, New York and many more have passed laws to protect kids from harms of Big Tech AI like chatbots and AI generated [child sexual abuse material]. Trump’s proposal to strip away these critical protections, which have no federal equivalent, threatens to create a taxpayer-funded death panel that will determine whether kids live or die when they decide what state laws will actually apply. This level of moral bankruptcy proves that Trump is just taking orders from Big Tech CEOs,” said Sacha Haworth, executive director of the Tech Oversight Project.

The task force would operate on the administration's argument that the federal government alone is authorized to regulate commerce between states.

Shakeel Hashim, editor of the newsletter Transformer, pointed out that that claim has been pushed aggressively in recent months by venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz.

President Donald Trump "and his team seem to have taken that idea and run with it," said Hashim. "It looks a lot like the tech industry dictating government policy—ironic, given that Trump rails against 'regulatory capture' in the draft order."

The DOJ panel would consult with Trump and White House AI Special Adviser David Sacks—an investor and cofounder of an AI company—on which state laws should be challenged.

The executive order would also authorize Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick to publish a review of "onerous" state AI laws and restrict federal broadband funds to states found to have laws the White House disagrees with. It would further direct the Federal Communications Commission to adopt a new federal AI law that would preempt state laws.

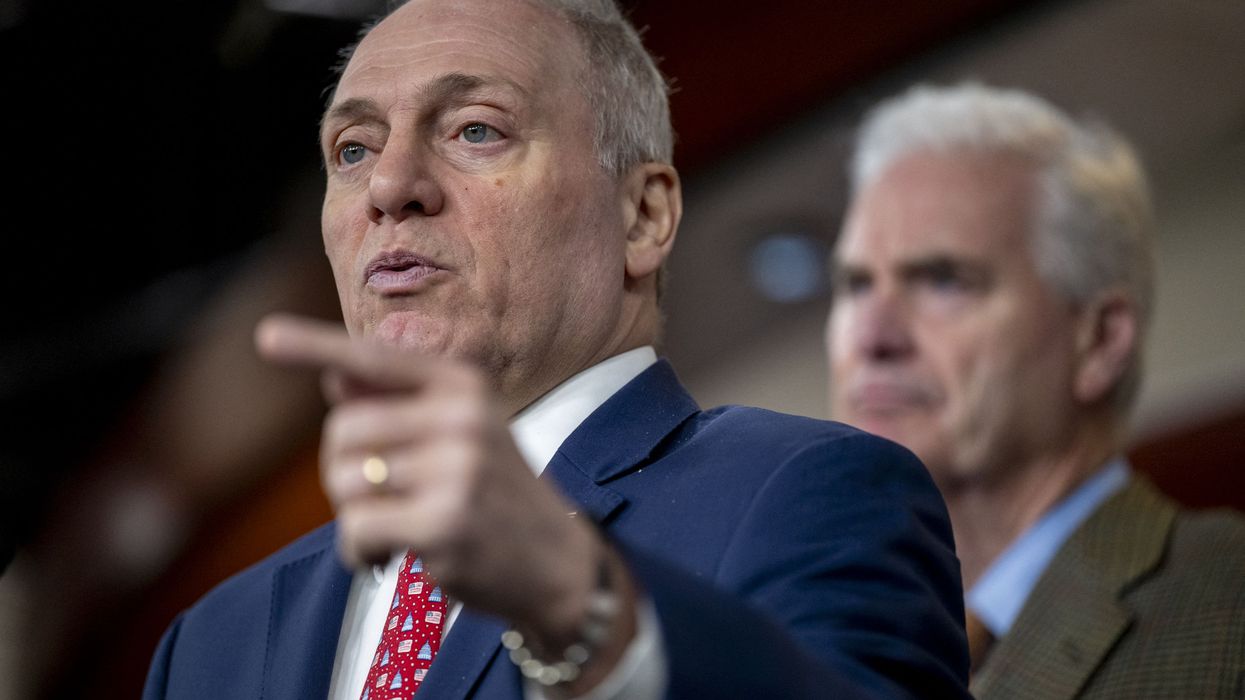

The draft executive order was reported days after Trump called on House Republicans to include a ban on state-level AI regulations in the must-pass National Defense Authorization Act, which House Majority Leader Steve Scalise (R-La.) indicated the party would try to do.

The multipronged effort to stop states from regulating the technology, including AI chatbots that have already been linked to the suicides of children, comes months after an amendment to the One Big Beautiful Bill Act was resoundingly rejected in the Senate, 99-1.

Travis Hall, director for state engagement at the Center for Democracy and Technology, suggested that legal challenges would be filed swiftly if Trump moves forward with the executive order.

"The president cannot preempt state laws through an executive order, full stop," Hall told NBC News. "Preemption is a question for Congress, which they have considered and rejected, and should continue to reject."

David Dayen, executive editor of The American Prospect, said harm the draft order could pose becomes clear "once you ask one simple question: What is an AI law?"

The draft doesn't specify, but Dayen posited that a range of statutes could apply: "Is that just something that has to do with [large language models]? Is it anything involving a business that uses an algorithm? Machine learning?"

"You can bet that every company will try to get it to apply to their industry, and do whatever corrupt transactions with Trump to ensure it," he continued. "So this is a roadmap to preempt the vast majority of state laws on business and commerce more generally, everything from consumer protection to worker rights, in the name of preventing 'obstruction' of AI. This should be challenged immediately upon signing."

The draft order was reported amid speculation among tech industry analysts that the AI "bubble" is likely about to burst, with investors dumping their shares in AI chip manufacturer Nvidia and an MIT report finding that 95% of generative AI pilot programs are not presenting a return on investment for companies. Executives at tech giant OpenAI recently suggested the government should provide companies with a "guarantee" for developing AI infrastrusture—which was widely interpreted as a plea for a bailout.

At Public Citizen, copresident Robert Weissman took aim at the White House for its claim that AI does not pose risks to consumers, noting AI technologies are already "undermining the emotional well-being of young people and adults and, in some cases, contributing to suicide; exacerbating racial disparities at workplaces; wrongfully denying patients healthcare; driving up electric bills and increasing greenhouse gas emissions; displacing jobs; and undermining society’s basic concept of truth."

Furthermore, he said, the president's draft order proves that "for all his posturing against Big Tech, Donald Trump is nothing but the industry’s well-paid waterboy."

"Big Tech companies have spent the past year cozying up to Trump—doing everything from paying for his garish White House ballroom to adopting content moderation policies of his liking—and this is their reward," said Weissman. "It’s a fabulous return on a very modest investment—at the expense of all Americans.”

JB Branch, the group's Big Tech accountability advocate, added that instead of respecting the Senate's bipartisan rejection of the earlier attempt to stop states from regulating AI, "industry lobbyists are now running to the White House."

"AI scams are exploding, children have died by suicide linked to harmful online systems, and psychologists are warning about AI-induced breakdowns, but President Trump is choosing to protect his tech oligarch friends over the safety of middle-class Americans," said Branch. "The administration should stop trying to shield Silicon Valley from responsibility and start listening to the overwhelming bipartisan consensus that stronger, not weaker, safeguards are needed.”