At the dawn of the twentieth century the industrial giants watched each other cautiously. The British sent high-ranking commissions to the United States and the United States sent similar groups to Britain and Germany. All were looking over their shoulders to see what made for economic greatness and what would ensure supremacy in the future… Earlier delegations focused on technology and physical capital. Those of the turn-of-the-century turned their attention to something different. People and training, not capital and technology, had become the new concerns…For the twentieth century to become the human capital century required vast changes in educational institutions, a commitment by governments to fund education, a readiness by taxpayers to pay for the education of other people’s children, a belief by business and industry that formal schooling mattered to them, and a willingness on the part of parents to send their children to school (and by youths to go). The transition occurred first in the United States and was accompanied by a set of “virtues” or principles, many of which can be summarized by the word “egalitarianism.”

In the 21st century, unfortunately, too many policymakers seem determined to squander this legacy by starving public education of money and legitimacy, often in the name of “school choice.” Their central claim (when they bother to make one with any clarity) is that public provision of goods or services is ineffective by definition and that a dose of private, market-like competition will lead to better schooling outcomes for the nation’s children.

This claim is weak on its logical face, as the conditions needed for market competition to lead to better outcomes clearly do not exist in the educational realm. Take just three obvious examples. First, unlike other goods and services, there is no option to forego education entirely. In other markets, if the private sector is doing a poor job at offering attractive options for a good or service, people can just consume other things. But the United States—rightly—mandates basic education for all kids. Second, competition works well when the cost of switching providers is small. If you get tired of prices or goods at Whole Foods, you can shop at Giant. By contrast, switching schools is an extraordinarily costly decision in time, administrative burden, and severed social networks. Third, competition works well in markets when a transaction only affects the buyer and seller—and not unrelated third parties. But if third parties are affected by a transaction (think of pollution affecting third parties when I decide to buy gasoline for my car), then private markets will fail to match costs and benefits. Universal schooling generates positive spillovers to society at large, meaning that individuals would be inclined to underinvest in education relative to the full benefits it provides.

The easiest way to boost educational outcomes is providing more public resources

To the degree any evidence is mobilized in support of the view that public education needs market-like disruption through “school choice” instruments like vouchers, it generally relies on outdated research claiming that public schools already have “enough” funding, and that additional resources would not generate better outcomes. If one believed that the level of public education resources was sufficient, then strategies aimed at changing the composition of these resources or how they were mobilized—say through privatization via vouchers—might make some sense.

But this is wrong on several fronts.

First, newer research with better methods confirms that more money for public schools does improve educational outcomes. And not only does more money improve schooling outcomes for children, it also has the largest beneficial effects on the performance of particularly disadvantaged students.

Such spending is not random and depends on a number of factors that are correlated with student success. For example, spending in a given district might rise as higher-income families move into the area and property values increase. These higher-income families might also be able to provide greater in home resources that will aid their children’s academic performance. Simple correlations between the level of district spending and student success might hence show a positive relationship, but the causality would not necessarily be running from district spending decisions to student success; both might instead be driven by a third variable, which is simply the level of family resources on average across the district.

Running the opposite direction, much school funding is explicitly compensatory, targeting students facing greater socioeconomic disadvantage to attempt to even out total resources (both in home and public) available to students for academic success. But if this greater spending targets students with fewer in home resources, it could show a negative relationship between levels of spending and student performance, but again will not be reflecting the causal effect of this spending.

The new research has overcome this key challenge in empirical assessments of the relationship between school spending and student outcomes: It found natural experiments that allow truly exogenous changes in school spending to be identified, and hence the effects on student achievement to reflect the causal effect of this spending. The exogenous changes that allowed for these examinations were largely court-ordered school finance reforms (SFRs).

For example, Jackson, Johnson, and Persico (2016) examined the impact of school finance reforms between 1972 and 2010, and found that a 10% increase in school spending for 12 years lead to increases in high school graduation rates, 7% higher wages, and 10% higher family incomes in adulthood for children from districts that saw the spending increase. Gains were concentrated among students in high-poverty households. Lafortune, Rothstein, and Schanzenbach (2018) similarly found that a $1,000 increase in per-pupil spending for low-income districts would reduce the test score gap between low- and high-income school districts within a state by roughly 0.18 standard deviations (SDs) following court-ordered SFRs, or by nearly 40% of the baseline gap.

In short, the evidence indicates that public schooling in the United States simply needs more resources to deliver even better student achievement—not some radical disruption in how it is delivered and by what institutions.

Second, vouchers don’t lead to better student achievement. Several high-quality studies have investigated the impact of recent voucher programs and have found notably worse outcomes for student achievement. In the first two years following Louisiana’s Scholarship voucher program, student achievement in language arts and math both decreased by as much as 0.34 SDs. In Ohio, under the Ed Choice program, students who went to private schools with a voucher performed worse than they would have had they remained in public schools. In Indiana, students that used the Indiana Choice Scholarship voucher program experienced an average achievement loss of 0.15 SDs in mathematics.

The promise of vouchers improving educational outcomes rests on assumptions that the private sector is always and everywhere more efficient than public providers of goods and services. But the private schools that expand or are created in response to the introduction of voucher programs are often of very poor quality. In the case of Milwaukee’s longstanding voucher programs, for example, researchers found that 40% of private voucher schools failed or closed down within the program’s first 25 years. Parents often belatedly realize that these schools are no improvement relative to public schools; this has lead a large share of students that took vouchers to return to public schools shortly after. In Milwaukee, nearly 20% of kids left voucher programs every year, with most coming back to public school.

Vouchers reduce public school resources, but introduce large new fiscal obligations overall

It would be bad enough if the introduction of vouchers simply funneled some students into poorly performing private schools for a stretch of time. But vouchers also affirmatively drain resources from the entire public education system—resources that would reliably produce better outcomes for children if they had stayed in public schools. Paradoxically, while vouchers are associated with significant drains from public school resources, they could actually boost the total fiscal cost of state support for education over time by shoveling more and more resources to (poorly performing, on average) private schools.

Arizona provides a cautionary tale. Arizona’s 2023 universal voucher program was forecast to cost $33 million in the first year and $65 million in the second. Instead, the program ended up costing $587 million in the first year and is projected to cost upwards of $708 million in 2024 fiscal year. Even smaller programs tend to be dramatically underestimated.

Part of this unexpected cost was the subsidy offered to parents who had already enrolled their kids in private schools: 75% of the first wave of applicants to the Arizona program were parents of students with no history of public school attendance, who could now tap taxpayer money to pay for their children’s private schools. Much of the cost of vouchers is essentially a subsidy for parents (many of them affluent) who never intended on using the public school system.

Other states have followed this pattern of introducing programs promised to be small and seeing them balloon in size. New Hampshire’s 2021 Educational Freedom Account was estimated to cost $300,000 in the first year and $3 million in the second, but in reality the bill cost $8.1 million in the first year, $14.6 million in 2022, and $25 million in the 2023-24 school year.

The rise of vouchers in the past 15 years represents an affirmative effort to erode public education by starving it of needed funding. Voucher proponents often want voters to think these programs simply broaden the suite of options enjoyed by parents and students. But the data tell a different story: Where significant voucher programs have been instituted, the resources available to public school children have decreased. Again, highly persuasive recent research shows that public school resources are crucial on the margin, and that more public resources reliably improve student achievement and economic outcomes later in life—while fewer public resources reliably harm education. Voucher programs that starve public resources for education are therefore deeply damaging.

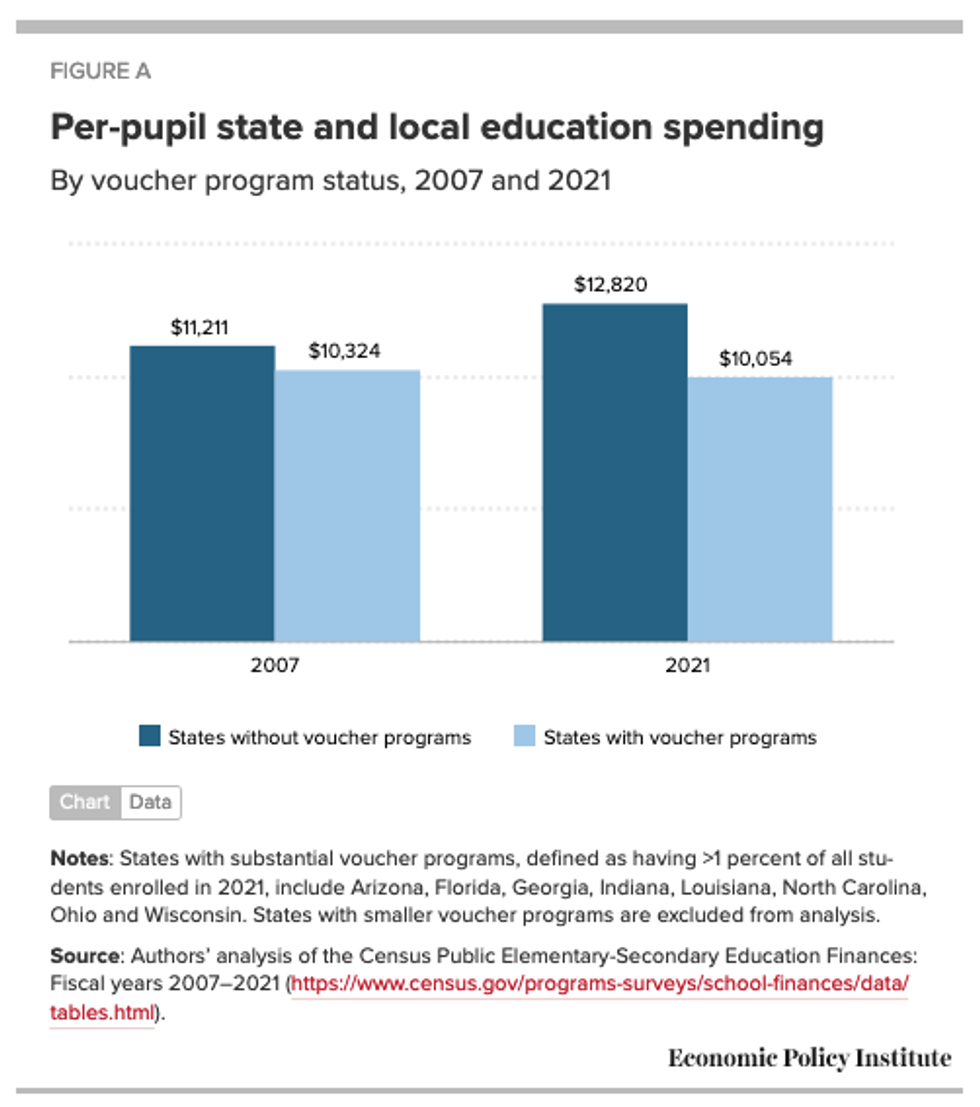

Figure A shows state and local per-pupil funding levels in 2007 and 2021 (expressed in 2020 dollars) for states that passed substantial voucher programs during the period (defined as having >1% of enrolled students using vouchers by 2021) as well as for states without any voucher programs. In 2007, the average difference in per-pupil spending between these two groups of states was around $900 (higher in states that did not subsequently pass significant voucher programs). Between 2007 and 2021, voucher programs grew significantly in one set of these states. By 2021, states without voucher programs were spending $2,800 more per-pupil—essentially more than tripling the spending advantage they had before the rise of voucher programs in the 2010s and early 2020s.

The failure to increase per-pupil funding leads to the erosion of public education services in all forms: everything from school meals, extracurricular activities, mental health and counseling services, vocational and technical programs, and investments in teacher quality and pay. It is also worth noting that flat per-pupil educational spending—even in inflation-adjusted terms—is effectively a decline in the quality of education over time. Take the example of teachers: In a growing economy, simply keeping real pay constant for teachers means that their pay, relative to other skilled and credentialed professionals, is declining. This decline in relative teachers’ pay (even with absolute pay levels flat) will put downward pressure on the quality of the teaching labor pool, as more and more people who could have been excellent teachers decide to choose higher-pay occupations.

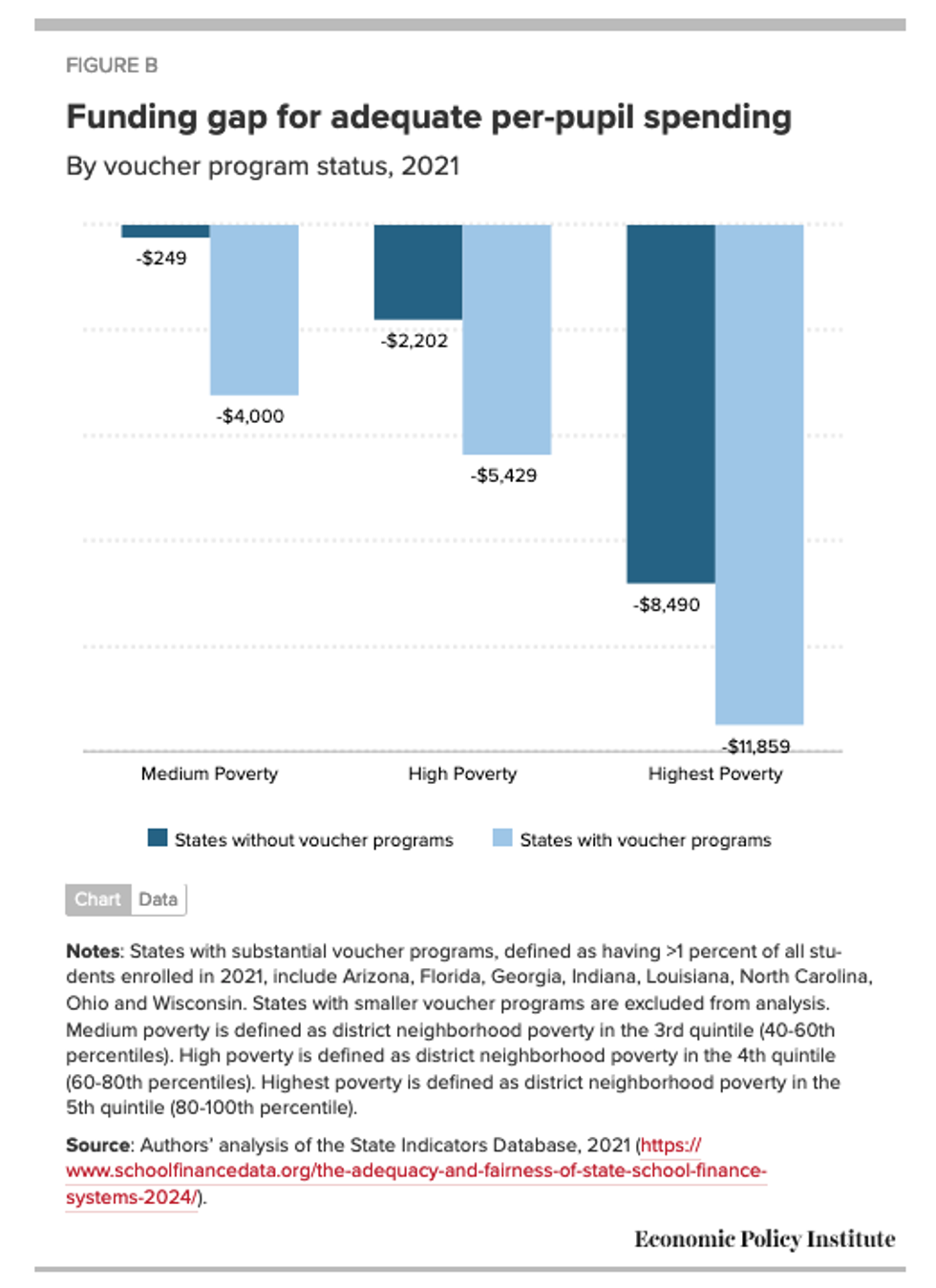

Stagnant spending in states with significant voucher programs has also left education funding in those states substantially below measures of funding adequacy. In school finance research, adequacy is defined as the level of funding needed in a district to ensure students reach an average level of student achievement. For the measure of adequacy used below, the outcome is achieving the national average of test scores. Adequacy measures account for needs that differ by district depending on influences like the socioeconomic status of the student population.

State constitutions mandate sufficient education funding for students to have access to an adequate education, regardless of students’ economic or social circumstances. For example, students in high-poverty districts will need more education funding than students in low-poverty districts to achieve the same outcome because they live in neighborhoods where there are fewer resources available to help them succeed. Several court cases in recent decades have found a constitutional responsibility for states to provide such adequate funding.

Figure B relies on total per-pupil spending data from the School Finance Indicator Database to assess the adequacy of school spending for states with large voucher programs and states without any voucher program, comparing the gap for students in medium-, high-, and highest-poverty districts in our two groups of states in 2021. A negative gap implies that state spending is inadequate, and students are not receiving the resources required to meet average academic achievement levels. Regardless of poverty status, states with substantial voucher programs in 2021 are not spending enough to meet students’ needs.

For medium-poverty districts, the adequacy gap is negative, but quite small in schools without a voucher presence (roughly $220 per pupil). In medium-poverty districts of states with a significant voucher presence, however, the adequacy gap is negative and very large—with actual spending lagging adequacy measures by $3,750 per pupil. In high-poverty districts, even states without vouchers have large adequacy gaps—roughly $2,200 per pupil. But these gaps are double the size in states with significant voucher programs—roughly $5,400 per pupil. Finally, adequacy gaps are shamefully large in both states without vouchers ($8,500 per pupil) and in states with significant vouchers ($11,900), but the difference remains quite high.

These results clearly show that school financing is far from perfect in states without voucher programs, but is far worse in states that have introduced these programs.

Conclusion

Vouchers are not a cost-free policy that simply adds on another education option for children—they are instead an intentional attack on universal public education, one of the crown jewels of U.S. society. Vouchers make no coherent economic sense, and the evidence shows that vouchers harm student achievement and expose state budgets to large future obligations that are hard to forecast, even while they divert spending away from public education. Our analysis shows that states that have introduced significant voucher programs over the past decade and a half have experienced significant declines in per-pupil spending relative to states without voucher programs. In short, the data clearly show that choosing to implement vouchers programs takes funding away from public education. The public spending declines associated with the introduction of vouchers will reliably cause significantly worse educational outcomes and will harm kids in high-poverty neighborhoods more than kids in low-poverty neighborhoods.

The rise of vouchers is especially damaging given that we now know what does boost educational outcomes: more spending on public education. Leaving these potential gains on the table and promoting voucher programs instead of investing in public education demonstrates that kids’ education is not a priority.