On the surface, the choice to rely on SAFs for green aviation makes all the sense in the world. Unlike hydrogen- or battery-powered aircraft, SAFs can be easily integrated into the existing infrastructure of air transport and support long-haul flights of six hours or more.

But there are two fundamental problems with this approach.

The best and most effective way to lower the carbon footprint of the aviation sector is simply to fly less.

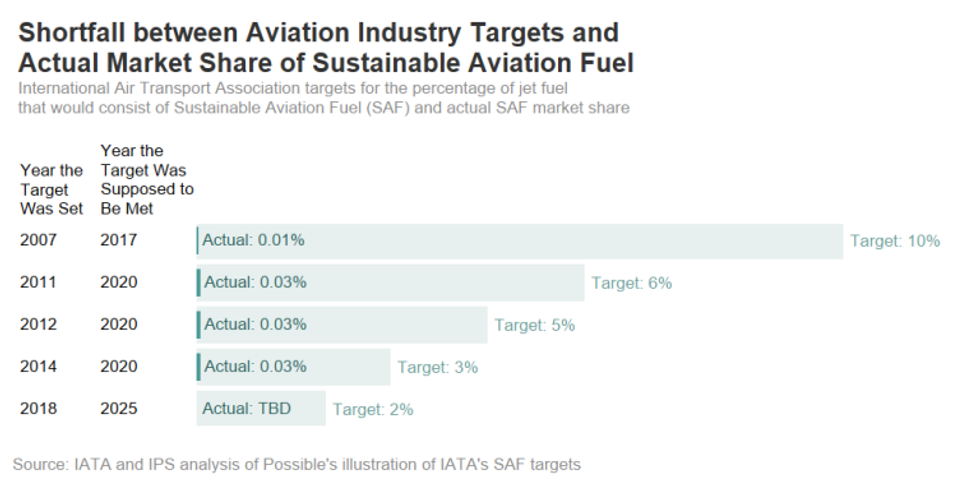

The first is that the aviation industry has an unreliable record of meeting SAF production targets. The International Air Transport Association (IATA), for example, announced in 2007 its goal to produce close to 9 billion gallons of SAFs by 2017. But this proved to be wishful thinking, and IATA proceeded to adjust its production targets lower and lower with each passing year to no avail. Even the

aim of 2% production share by 2025 is still too grand. SAFs currently represent a negligible 0.2% of total jet fuel supply, causing a majority of airline executives to be skeptical about their ability to meet their self-declared climate goals by mid century.

Part of the challenge in bringing more SAFs to market is the costs associated with its production. SAFs are

more than twice as expensive as their petroleum-based counterparts. The aviation industry, producers of alternative energies, and their representative bodies are depending on the government to play a more active role in making the price of SAFs more competitive and expanding its availability on the international market through subsidies and tax incentives.

But this ignores the second problem: the rapid expansion of SAFs actively undermines the goal of achieving net zero.

That is because biogenic and biomass feedstocks are needed to immediately increase SAF production, requiring land-use changes and the destruction of

nature-based solutions to climate change. In other words, agricultural land would prioritize the energy demands of an ever-growing aviation sector instead of growing crops to feed the planet. It will also disincentivize the regrowth of trees that remove and store carbon from our atmosphere.

Research and

analysis of a dozen different roadmaps for aviation decarbonization through the large-scale adoption of SAFs demonstrate a negative environmental outcome. It paradoxically sabotages its own aspirations for achieving net zero due to the decades-long lag in biological carbon sequestration. Even putting those concerns aside, research and expert opinion dispute the ability of SAFs to meet the growing needs and demands of the aviation industry.

This puts the Biden administration’s SAF production target of

3 billion gallons per year by 2030—from the current 24.5 million gallons produced in 2023—into a new perspective. The World Resources Institute has condemned the administration’s new guidance for allowing the inclusion of crop-based biofuels like ethanol to qualify as a SAF feedstock. Corn-based ethanol is not sustainable and its inclusion directly undermines the government’s stated climate goals. And since the administration is preparing to grant lavish subsidies and tax credits to SAF producers, this has the potential to be a massive misallocation of public resources.

The best and most effective way to lower the carbon footprint of the aviation sector is simply to fly less. This is especially true for private aviation; a mode of transportation that fully epitomizes carbon inequality. It is the ultrawealthy who fly in luxury private jets and, as a result, emit

10 times more pollutants per passenger compared to commercial air travelers.

A more efficient use of our public resources is to invest in the decarbonization of other vital sectors of the economy. The electrification of our bus fleet and the construction of green public transportation are low-hanging fruit. Those are some of the many steps we need to take to usher in the much-needed green transition and save our planet from climate catastrophe.