SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

The SDGs are largely an investment agenda into human capital and infrastructure, yet many developing countries cannot finance these investments at reasonable terms.

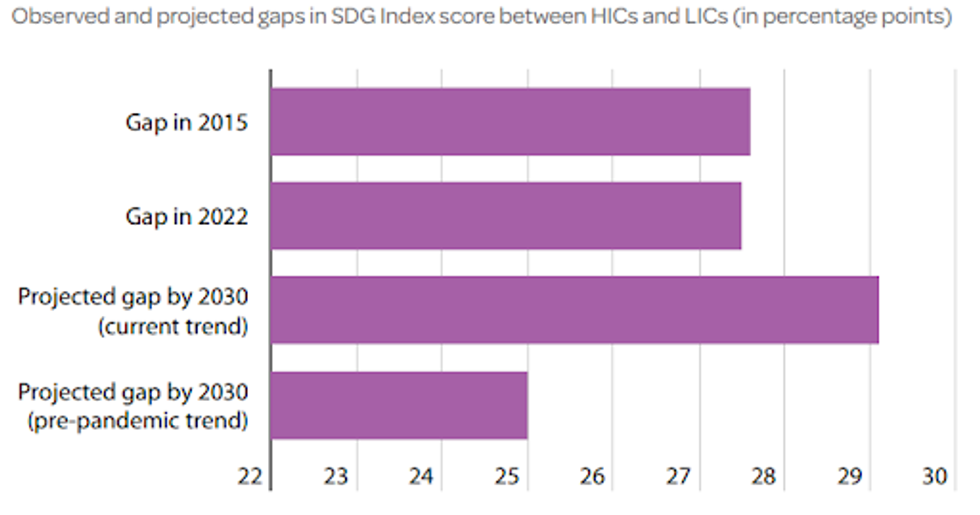

July 2023 was the hottest month ever recorded on Earth. From the rising impacts of climate change evidenced by the deadly wildfires across the world to the growing global inequities, it is clear that we have reached a decisive moment for achieving sustainable development. Furthermore, the gap between rich and poor countries on sustainable development outcomes is at risk of being larger in 2030 than it was in 2015, as highlighted in the 2023 Sustainable Development Report (which includes the SDG Index).

This is largely due to inefficiencies in the international financing system for financing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). To avoid a lost decade for convergence in sustainable development, we need long-term national SDG plans, backed by adequate financing, combined with global and regional cooperation.

The SDGs are largely an investment agenda into human capital and infrastructure, yet many developing countries cannot finance these investments at reasonable terms. The SDG financing gap was recently estimated by the United Nations at $4 trillion (or around 4% of world output). A rather modest amount relative to the size of the global economy, but very large relative to developing countries’ gross domestic product (likely 10-20 % or more). High-income countries managed to mobilize more than $17 trillion in post-Covid-19 recovery at zero or near-zero interest rates. By contrast, many developing countries lack access to capital markets, and even if they have access, they pay higher interest rates and face shorter repayment terms. This is the perfect recipe for getting stuck into liquidity crises, the “poverty trap,” and social unrest.

While it is often argued that the high interest rates faced by developing countries simply compensate for their higher risks of default, this presumption is contradicted by the historical record: The higher interest rates more than compensate for the higher risks of default of developing countries. As documented by Meyer, Reinhart, and Trebesch (2022), the long-term returns on risky sovereign bonds have been far higher than the returns on “safe” United States and United Kingdom securities, even taking into account the episodes of default. In reality, the higher interest rates faced by developing countries reflect two fundamental inefficiencies of the international financial markets:

Access to financing must be linked with SDG gaps and countries’ efforts to achieve sustainable development. There are two crucial levers to increase access to long-term SDG financing in developing countries.

First, sovereign risk-rating agencies and financial institutions at large must capture the growth potential of investing into sustainable development and better understand countries’ SDG efforts. As emphasized by U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres:

The divergence between developed and developing countries is becoming systemic—a recipe for instability, crisis, and forced migration. These imbalances are not a bug, but a feature of the global financial system. They are inbuilt and structural. They are the product of a system that routinely ascribes poor credit ratings to developing economies, starving them of private finance.

Whether it is via sustainability-themed bonds or via significant revisions of credit-risk rating methodologies, the cost of borrowing and maturities must better reflect SDG efforts and commitments in developing countries. There is a clear business case for this. When Benin worked with private financial institutions to issue the first African SDG Bond in July 2021, it managed to mobilize €500 million with a 20-base points greenium (i.e. lower cost of borrowing than its typical sovereign bond) and an average maturity of 12.5 years from the international capital market. New mechanisms, such as new swap lines and the expansion of the IMF Special Drawing Rights, can help increase guarantees and extend lender-of-last-resort protection. Partnerships between private financial institutions, governments, and civil society organizations in the development of long-term pathways and investment frameworks, as well as in the monitoring of policies and impacts, will help reduce risks and increase accountability.

Second, Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) should operate at a much higher scale. Thanks to their governance system, MDBs—including the World Bank and regional development banks—can borrow and lend to their member countries at lower interest rates. When MDBs borrow on international markets, they offer more guarantees to lenders than individual countries because the loans are guaranteed by all their members. Yet, MDBs operate at a scale which is largely insufficient.

In September 2022, Guterres introduced the SDG Stimulus. As emphasized by Sustainable Development Solutions Network Leadership Council members, the urgent objective of the SDG Stimulus is to address—in practical terms and at scale—the chronic shortfall of international SDG financing facing the low income countries and low-and-middle-income countries, and to ramp up financing flows by at least $500 billion by 2025. The most important component of the stimulus plan is a massive expansion of loans by the MDBs, backed by new rounds of paid-in capital by high-income country members. Unfortunately, the commitment made at the recent Paris Summit for a Global Financing Pact—an overall increase of $200 billion of MDBs’ lending capacity over the next 10 years (at $20 billion per year)—remains vastly insufficient.

At the global level, the SDG financing gap is largely the result of missed investment opportunities caused by an inappropriate financing framework. Moving forward, we must channel a larger share of global savings (currently equivalent to around $28 trillion per year) to activities that promote sustainable development, especially in developing countries. And the notion of risk must be reconsidered to recognize the long-term returns of investing into sustainable development and the cost of inaction.

In any case, greater access to financing from private capital markets, debt relief & restructuration, increased Official Development Assistance, foreign direct investments, and MDB lending must be associated with long-term investment planning, fiscal frameworks, project implementation, financial operations, and relations with partner institutions in developing countries, in order to be able to channel much larger funds into long-term sustainable development.

This year’s United Nations General Assembly and SDG Summit, and the upcoming G20 meeting in India, are important milestones to reform the global financial system and to promote cooperation and pathways for sustainable development.

The poorer countries are demanding an end to a world dominated by the rich—as well they should.

The key to economic development and ending poverty is investment. Nations achieve prosperity by investing in four priorities. Most important is investing in people, through quality education and health care. The next is infrastructure, such as electricity, safe water, digital networks, and public transport. The third is natural capital, protecting nature. The fourth is business investment. The key is finance: mobilizing the funds to invest at the scale and speed required.

In principle, the world should operate as an interconnected system. The rich countries, with high levels of education, healthcare, infrastructure, and business capital, should supply ample finance to the poor countries, which must urgently build up their human, infrastructure, natural, and business capital. Money should flow from rich to poor countries. As the emerging market countries became richer, profits and interest would flow back to rich countries as returns on their investments.

That’s a win-win proposition. Both rich and poor countries benefit. Poor countries become richer; rich countries earn higher returns than they would if they invested only in their own economies.

Strangely, international finance doesn’t work that way. Rich countries invest mainly in rich economies. Poorer countries get only a trickle of funds, not enough to lift out of poverty. The poorest half of the world (low-income and lower-middle-income countries) currently produces around $10 trillion a year, while the richest half of the world (high-income and upper-middle-income countries) produces around $90 trillion. Financing from the richer half to the poorer half should be perhaps $2-3 trillion year. In fact, it’s a small fraction of that.

The problem is that investing in poorer countries seems too risky. This is true if we look at the short run. Suppose that the government of a low-income country wants to borrow to fund public education. The economic returns to education are very high, but need 20-30 years to realize, as today’s children progress through 12-16 years of schooling and only then enter the labor market. Yet loans are often for only 5 years, and are denominated in US dollars rather than the national currency.

Suppose the country borrows $2 billion today, due in five years. That’s okay if in 5 years, the government can refinance the $2 billion with yet another five-year loan. With five refinance loans, each for five years, debt repayments are delayed for 30 years, by which time the economy will have grown sufficiently to repay the debt without another loan.

Yet, at some point along the way, the country will likely find it difficult to refinance the debt. Perhaps a pandemic, or Wall Street banking crisis, or election uncertainty will scare investors. When the country tries to refinance the $2 billion, it finds itself shut out from the financial market. Without enough dollars at hand, and no new loan, it defaults, and lands in the IMF emergency room.

Like most emergency rooms, what ensues is not pleasant to behold. The government slashes public spending, incurs social unrest, and faces prolonged negotiations with foreign creditors. In short, the country is plunged into a deep financial, economic, and social crisis.

Knowing this in advance, credit-rating agencies like Moody’s and S&P Global give the countries a low credit score, below “investment grade.” As a result, poorer countries are unable to borrow long term. Governments need to invest for the long term, but short-term loans push governments to short-term thinking and investing.

Poor countries also pay very high interest rates. While the US government pays less than 4 percent per year on 30-year borrowing, the government of a poor country often pays more than 10 percent on 5-year loans.

The IMF, for its part, advises the governments of poorer countries not to borrow very much. In effect, the IMF tells the government: better to forgo education (or electricity, or safe water, or paved roads) to avoid a future debt crisis. That’s tragic advice! It results in a poverty trap, rather than an escape from poverty.

The situation has become intolerable. The poorer half of the world is being told by the richer half: decarbonize your energy system; guarantee universal healthcare, education, and access to digital services; protect your rainforests; ensure safe water and sanitation; and more. And yet they are somehow to do all of this with a trickle of 5-year loans at 10 percent interest!

The problem isn’t with the global goals. These are within reach, but only if the investment flows are high enough. The problem is the lack of global solidarity. Poorer nations need 30-year loans at 4 percent, not 5-year loans at more than 10 percent, and they need much more financing.

Put more simply, the poorer countries are demanding an end to global financial apartheid.

There are two key ways to accomplish this. The first way is to expand roughly fivefold the financing by the World Bank and the regional development banks (such as the African Development Bank). Those banks can borrow at 30 years and around 4 percent, and on-lend to poorer countries on those favorable terms. Yet their operations are too small. For the banks to scale-up, the G20 countries (including the US, China, and EU) need to put a lot more capital into those multilateral banks.

The second way is to fix the credit-rating system, the IMF’s debt advice, and the financial management systems of the borrowing countries. The system needs to be reoriented towards long-term sustainable development. If poorer countries are enabled to borrow for 30 years, rather than 5 years, they won’t face financial crises in the meantime. With the right kind of long-term borrowing strategy, backed up by more accurate credit ratings and better IMF advice, the poorer countries will access much higher flows on much more favorable terms.

The major countries will have four meetings on global finance this year: in Paris in June, Delhi in September, the UN in September, and Dubai in November. If the big countries work together, they can solve this. That’s their real job, rather than fighting endless, destructive, and disastrous wars.

A historic event took place on Earth Day 2016. It was a decisive moment for the planet. On Friday, April 22nd around 60 heads of state gathered at the United Nations in New York for the signing of the Paris Climate Agreement. 175 governments took the first step of signing onto the deal and according to the White House at least 34 countries, representing 49% of greenhouse gas emissions have formally ratified the Paris Agreement. It was 'the largest ever single-day turn-out for a signing ceremony,' indicating 'strong international commitment to deliver on the promises.

I was at COP21 in Paris when negotiators finally agreed the Paris Agreement, the first legally binding global climate deal: the culmination of 21 years of international negotiation and United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) process: a massive global political mobilization in response to the looming threat of catastrophic climate change. It scales up ambition from the previous international instrument, the Kyoto Protocol, by placing mitigation and adaptation obligations on all Parties. The Agreement includes elements of previous international agreements and follows on from the Kyoto Protocol and the shameful failure of the Copenhagen Accord. The Paris Agreement is an unprecedented evolution in both international law and climate change law. We all hope that it will be enough to save the planet.

The program for the opening ceremony included messages from civil society, a UN messenger for Peace, participation of schoolchildren and a performance by the Julliard Quintet. The ceremony itself was preceded by a high level debate on climate change and sustainability. These are perceived as hopeful signs that the Paris Agreement will be inclusive and fulfill the needs of all, including the most vulnerable. "At the ceremony Hindou Oumarou Ibrahim, an indigenous women's leader from Chad, called on countries to follow through on their promises. Temperatures in her country were already a blistering 48C (118F), she said, and climate change threatened to obliterate billions spent on development aid over recent decades."

I welcome the commitments of the Paris Agreement, which "aims... to strengthen the global response to the threat of climate change, in the context of sustainable development and efforts to eradicate poverty... to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5degC above preindustrial levels." The agreement commits to "adapt to the adverse impacts of climate change and foster climate resilience," to "Making finance flows consistent with a pathway towards low greenhouse gas emissions and climate resilient development," all "implemented to reflect equity and the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities." These pledges are a great step forward in the race against catastrophic climate change.

I am very concerned, however, about the Agreement's provision to hold "the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2 degC above pre-industrial levels." This is a dangerous equivocation. By now we all know that a 2degC target is woefully inadequate.

THE 1.5 DEGREE CELSIUS TARGET

Some critics have been skeptical about the Paris Agreement, and expressed doubts that governments have either the intention or the ability to live up to their promises -- I share their doubts. NASA climate scientist Professor James Hansen, one of the world's foremost authorities on climate change, said of the agreement, "It's a fraud really, a fake... It's just bullshit for them to say: 'We'll have a 2C warming target and then try to do a little better every five years.' It's just worthless words. There is no action, just promises.'"George Monbiot writes of the Paris Agreement, "By comparison to what it could have been, it's a miracle. By comparison to what it should have been, it's a disaster."

Scientists at MIT say that under the current Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDCs) the global average temperature will soar by as much as 3.7 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels by 2100. This is far above the 1.5 degree Celsius target, which, as President Hollande memorably stated at the opening of COP21 in Paris, is the 'absolute ceiling' for global temperature rise if we are to prevent climate catastrophe. Anything above 1.5 degrees C is a death sentence for us and for the planet.

A new report released in the Earth Systems Dynamics Journal in April 2016 maps the different consequences between a 1.5 and a 2 degree Celsius warmer world. Unsurprisingly, the 2 degree scenario is apocalyptic: extreme weather events, water scarcity, reduced crop yields, coral reef degradation and sea-level rise. We are already well on our way to creating this future. 2014 saw record-breaking temperatures and 2015 was the hottest year on record. 2016 has already surpassed previous temperature highs: in February, the global temperature was 1.34C above the average from 1951-1980, according to Nasa data.

We have now arrived at the tipping point. There is no more time for procrastination, or half-measures. The time is now, and there is no Plan B.

POLITICAL WILL

Enforcing the Paris Agreement will need world leaders' commitment for many years to come. The agreement is vulnerable, because it is subject to the vagaries of political will, and to changes in administration. President Obama has, to date, been more committed to combating climate change than any other U.S. President in recent history, and he is a key supporter of the agreement.

What happens, it has been asked, when Obama's administration comes to its end? What if the unthinkable happens and Donald Trump takes the White House? Would Trump feel bound by the Paris Agreement and continue the US's current trajectory towards decarbonization and lowering emissions? Not bloody likely. Hopefully the US will escape the fate of a Trump administration. The only hope is that Hillary Clinton, if she becomes the next President of the U.S., will demonstrate the same, or greater commitment as President Obama has done to the Paris Agreement.

THE RENEWABLE ENERGY REVOLUTION

In order for the Paris Agreement to keep the warming of the world below the 1.5 degree Celsius target governments must commit to reducing CO2 emissions "in accordance with best available science." They must commit to halt the burning of fossil fuels, which have already formed a toxic "blanket" around the earth - they must "leave it in the ground." On April 22nd, at the signing ceremony, more than 170 countries vowed to put an end to the age of fossil fuels. These are fine words; but they will remain only words if countries don't commit to eradicating fossil fuels from our energy systems. They must embark upon a renewable energy revolution now.

The transition to renewable energy is urgent and necessary; and it is already bringing great economic benefit across the world. The International Energy Agency has forecast that renewables will produce more power than coal within 15 years. In July 2015, on a windy day, Denmark's wind farms produced between 116 and 140 percent of the national electricity requirements. Mexican energy firm TAU has saved so much through use of renewable energy, that they provide their customers with as much free electricity as they wish between 9 p.m. and 6 a.m. "A network of land-based 2.5 MW wind turbines... operating at as little as 20% of their rated capacity, could supply more than 40 times current worldwide consumption of electricity, more than 5 times total global use of energy in all forms," according to Harvard University. If solar's current rate of growth continues, its output could match world power demand in just 18 years time. Big banks like UBS and Citigroup are investing heavily in solar, a market Deutsche Bank estimates will be worth a staggering $5 trillion in 2035. 'The sun has become mainstream, and... promises to democratise energy generation,' writes Leonie Greene in the Telegraph.

CO2 emissions reductions that meet the ambition of the Paris Agreement can only be achieved if a transition occurs from fossil fuels to renewables and if the 196 countries that gathered in Paris implement what the Agreement sets out on sequestration and decarbonisation. Article 4.1 of the Agreement states that "In order to achieve the long-term temperature goal ... Parties aim to reach global peaking of greenhouse gas emissions as soon as possible ... and to undertake rapid reductions thereafter in accordance with best available science, so as to achieve a balance between anthropogenic emissions by sources and removals by sinks of greenhouse gases in the second half of this century..."

One of the highlights of COP21 was Al Gore's speech "Impacts and Solutions to the Climate Crisis." Before a packed crowd of more than 2,000 people he sounded the death knell for fossil fuels with a sobering and powerful address, in which he championed the viability of renewable energy.

However, not everyone has seen the (solar-powered) light. Oil and gas are currently the cheapest they have been for many years and this is a dangerous incentive for energy corporations. "A critical point is that while the world's governments have signed on the dotted line, the world's companies have not... As long as fossil fuel energy is cheaper than renewables, oil gas and coal will be dispensed by the energy companies and burned by us all in vast quantities." Herbert Girardet writes in his article "COP-out in Paris," in Resurgence and Ecologist magazine, May/ June 2016. China, India and Indonesia are investing as heavily as ever in coal-powered electricity generation. Here in Great Britain, Prime Minister David Cameron has enthusiastically adopted fracking, touting it as the solution for energy independence for the UK despite the irrefutable evidence that fracking causes earthquakes, contamination of aquifers, leakage of toxic chemicals into the ground, air pollution, increased road traffic and significantly contributes to climate change. Each well drilled requires millions of litres of water, which places an immense strain on resources.

EXTREME WEATHER EVENTS

In his speech Al Gore mentioned the Weather Disasters report from the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNISDR), released a week before COP21 got underway, which details how 90% of the natural disasters during the last 20 years have been caused by extreme weather events. The report records 6,457 floods, storms, heat waves, droughts and other weather-related disasters, claiming the lives of 606,000 people, an average of some 30,000 per year, with an additional 4.1 billion people injured, left homeless or in need of emergency assistance. Gore said "This is the acceleration of the climate crisis ... It's like a nature hike through the book of Revelations."

The figures in the report for this year end in August 2015, but -- needless to say -- weather related disasters continue to ravage the world. In the whole of 2015 earthquakes, floods, heat waves and landslides left 22,773 people dead, affected 98.6 million others and caused $66.5bn (PS47bn) of economic damage. In December 2015 a powerful winter cyclone left devastation across the globe, leading to two tornado outbreaks in the United States and disastrous river flooding, driving temperatures in the North Pole up to 50 degrees above average. On 13 January this year a huge, dry electrical storm set more than 70 fires rampaging across the island of Tasmania, destroying most of the island's UNESCO world heritage site, which contained unique, ancient and irreplaceable ecosystems, including many trees that were over a thousand years old. This month devastating floods killed 53 people in Pakistan alone.

FOREST LANDSCAPE RESTORATION AND THE BONN CHALLENGE

In order to preserve the planet and combat climate change, we must preserve the forests - between now and 2020 alone, we stand to lose 1,460,000,000 acres of tropical forest and 273,750 species. We must also restore degraded, and deforested land to purpose. There are 2 billion hectares of degraded and deforested land across the world with potential for restoration. Restoration of degraded and deforested lands is not simply about planting trees. People and communities are at the heart of the restoration effort, which transforms barren or degraded areas of land into healthy, fertile working landscapes. Restored land can be put to a mosaic of uses such as agriculture, protected wildlife reserves, ecological corridors, regenerated forests, managed plantations, agroforestry systems and river or lakeside plantings to protect waterways.

The Bonn Challenge was established by the German Government and the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) at a ministerial roundtable in September 2011. It is the largest restoration initiative the world has ever seen. The objective of the Bonn Challenge was originally to restore 150 million hectares of degraded and deforested land across the world by 2020. The New York Declaration on Forests raised the Bonn Challenge ambition in September 2014 by calling for restoration of an additional 200 million hectares by 2030, bringing the total target to 350 million hectares by 2030.

Achieving the 350 million hectare by 2030 goal would result in estimates of 0.6 - 1.7 Gt CO2 sequestered per on year average, reaching 1.6 - 3.4 Gt per year in 2030 and totalling 11.8 - 33.5 Gt over the period 2011-2030. Even restoring 150 million hectares would capture 47 Gigatonnes of CO2, and reduce the emissions gap by 17%. Forest restoration is invaluable in the race to tackle climate change. That is why, in 2012, I became IUCN Ambassador for the Bonn Challenge. Not only is forest landscape restoration a critical tool against climate change, it is an issue of the most basic human rights: the right to food, shelter, clean water and sustainable livelihoods. The Bianca Jagger Human Rights Foundation (BJHRF) of which I am Founder, President and Chief Executive, is committed to forest conservation and restoration. Almost 20 million hectares have already been pledged by governments, communities and the private sector. Commitments of further 40 million hectares are being finalised.

INDIGENOUS PEOPLE'S RIGHTS

I am concerned by the lack of protection for the rights of indigenous peoples in the Paris Agreement, who have time and again been proven the best custodians of ecosystems, including forests. According to Victoria Tauli-Corpuz, UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, "studies over the last year have shown that indigenous peoples outperform every other owner, public or private entities on forest conservation." According to the Center for World Indigenous Peoples, it was pressure from the United States, the European Union, and Norwegian delegates at COP21 which 'caused reference to the "rights of Indigenous peoples" to be cut from the binding portion of the Paris Agreement, relegating the only mention of Indigenous rights to the purely aspirational preamble.' Megan Davis, UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues Chair, said in her statement to the COP, "Sadly, the agreement asks States to merely consider their human rights obligations, rather than comply with them."

The critical role of indigenous people in combating climate change is recognised in the Paris Agreement -- but their rights are not protected. Article 7.5 of the Paris Agreement acknowledges "that adaptation action should follow a country-driven, gender-responsive, participatory and fully transparent approach, taking into consideration vulnerable groups, communities and ecosystems, and should be based on and guided by the best available science and, as appropriate, traditional knowledge, knowledge of indigenous peoples and local knowledge systems."

WOMEN

Article 7.5's language regarding women, "a gender-responsive... approach," is also weak and non-binding. It has long been established that women are disproportionately affected by climate change, especially in poorer countries. They are often most responsible for food production, household water supply and energy for heating and cooking - activities which will be seriously impacted by climate change. Yet women are often underrepresented or excluded from decision-making.

We cannot combat climate change without involving all stakeholders, including women and indigenous people, and their rights should have been at the heart of the Paris Agreement.

FINANCING

The Agreement provides $100 bn in financing to compensate poorer countries' for 'loss and damage,' mitigation and adaptation. But this is a drop in the ocean, to put it mildly. Much more financing is needed to ensure that low lying and developing countries don't pay the price for decades of reckless gas guzzling, coal burning and emissions by the richest countries.

CONCLUSION

To hold "the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2 degC above pre-industrial levels" is a mockery. Much as I applaud the historic diplomatic achievements the agreement represents, the treaty contains fatal flaws that threaten us and the planet. This is the most important treaty the world has ever known; world leaders should have come away with an agreement that is bold and ambitious enough to save us from climate catastrophe. As the climate demonstrators at COP21 called out, as they assembled peacefully in the conference halls and Paris streets, as was written large on the signs they carried aloft: it is "1.5 to stay alive."