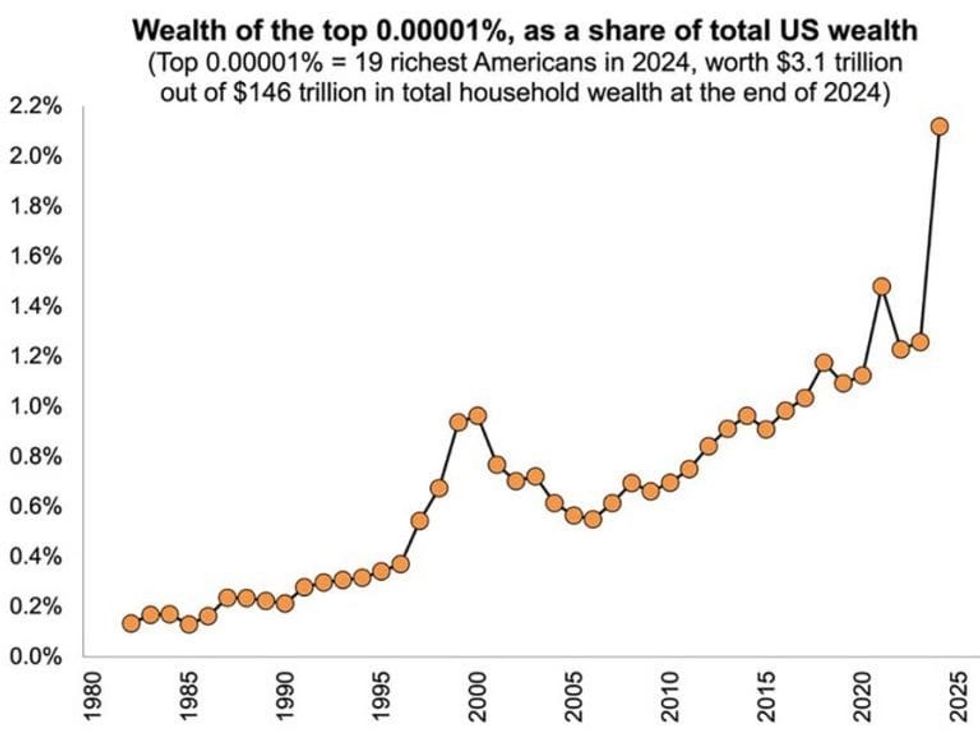

If 2% doesn’t seem to you like all that much, consider that this $3.1 trillion amounts to one-50th of our country’s wealth. We have, of course, exactly 50 states. The 19 Americans in this top 0.00001% hold personal net worths ranging from $50 billion to $360 billion. They together control the same amount of wealth as an average American state—think Massachusetts or Indiana—with a population of about 7 million people.

And the growth of our top 0.00001%’s wealth share over the years has been geometric, not linear. If policy choices over the next 42 years allow the trend of the past 42 years to continue, our top 0.00001 percenters won’t merely increase their wealth share from 2 to 4%. They will be increasing their wealth share 10-fold, to about 20%.

Will what’s left of American democracy survive for much longer if this wealth-concentrating trend continues?

Decades of policy failures have led to the concentration of wealth—and power—into so few hands that we are seeing our democracy crumble before our eyes.

Nearly a century ago, former Supreme Court jurist Louis Brandeis famously warned us: “We may have democracy, or we may have wealth concentrated in the hands of a few, but we cannot have both.”

We’re now seeing the nightmare scenario Brandeis feared—an oligarchic subversion of American democracy—play out in real time. We can argue politely about whether any single billionaire represents a policy failure. But having our nation’s three richest billionaires—Musk, Bezos, and Zuckerberg—sitting front and center at the inauguration of a billionaire president sure looks like we have a president answerable to oligarchs, not America’s voters.

An extreme concentration of oligarchic-level wealth, Brandeis feared, can easily translate into an extreme concentration of political power. To believe that this concentration has not occurred here in the United States rates as totally delusional. Musk spent over $250 million on U.S. President Donald Trump’s 2024 campaign, less than one one-thousandth of his personal fortune, yet enough to overwhelm the campaign finance system.

Musk, maybe more significantly, used his control over a powerful social media platform, X, to promote Trump’s campaign. Bezos and another billionaire, Patrick Soon-Shiung, demanded that the editorial boards of the newspapers they own, The Washington Post and the Los Angeles Times, not run editorials endorsing Trump’s opponent, former Vice President Kamala Harris.

Let’s remember that each of the country’s four wealthiest Americans—Musk, Zuckerberg, Bezos, and Ellison—controls at least one major media outlet or social media platform.

Let’s also remember that Musk, nearly immediately upon Trump taking office, began making unilateral decisions that are leading to the firing of tens of thousands of federal workers, the termination of life-saving foreign aid, and, if lawsuits don’t prevent it, the dismantling of entire federal agencies.

Decades of policy failures have led to the concentration of wealth—and power—into so few hands that we are seeing our democracy crumble before our eyes. For nearly half a century, everything from wage and labor policies to antitrust enforcement and intellectual property and trade standards have been moving us in the direction of more concentrated wealth.

In inflation-adjusted dollars, the federal minimum wage today stands at half its 1968 level. Over the past 50 years, union density has plummeted. The market power in virtually every major industry now sits massively concentrated in just a handful of giant corporations.

Against all these trends, tax policy remains our last line of defense, our firewall against the power of our wealthiest.

Think about things this way: Our policy choices in areas outside taxes—labor, wages, antitrust—all impact our national concentration of income. These policy choices drive the sharing of our country’s income between labor and capital and between consumers and businesses. And these policies have been driving an ever larger share of our nation’s income to those at the top.

Tax policy, by contrast, governs the conversion of income into wealth. Without taxation, necessary living expenses would cause income and wealth inequality to deepen over time—because those with smaller incomes must devote a larger portion of their income to basic living expenses. The passive income generated by the resulting unequal distribution of wealth—dividends and interest income, for instance—then proceeds to drive income inequality still higher in future years, causing the sharing of income remaining after living expenses to become even more skewed in favor of our richest.

With these dynamics in play, progressive income and wealth taxation becomes a necessary counterbalance to income inequality. Absent progressive taxation, income and wealth inequality will continuously worsen. The greater the level of income inequality, the more progressive the system of taxation necessary to counteract that concentration.

From this perspective, America’s tax policy choices have been an abject failure for nearly 50 years. Our top 1%’s share of our country’s income has more than doubled since 1980. Our tax system has become hugely less progressive. Regressive taxes like federal payroll taxes and state-level sales and property taxes have increased, while the gains from federal income tax cuts have flowed disproportionately to those at the top.

Between 1980 and today, the top federal income tax rate on paycheck income—the only substantial income that flows to most American households—has fallen by about one-fourth, from 50% to 37%. But the decline in the top income tax rate on dividends—income that flows primarily to major corporate shareholders—has fallen from 70 to 20%.

And these numbers just describe the surface of our current tax-cut scene. The investment gains of the ultra-rich compound tax-free until the underlying investments get sold. At sale, these gains face a one-time tax rate of 23.8%. That 23.8% translates into an equivalent annual tax rate that can run under 5%. And if a rich investor dies with billions of untaxed capital gains, all those gains totally escape any income-tax levy.

A tax system, to effectively contain the concentration of a society’s wealth, must contain a mechanism to tax either wealth itself, the income from that wealth, or the intergenerational transfer of wealth—or some combination of the three. America’s current tax system falls short on all these counts.

The income subject to federal income tax often represents only a fraction of the actual economic income that’s filling American billionaire pockets. Investment gains go untaxed unless and until investment assets get sold. The federal estate and gift tax system—originally intended to tax the intergenerational transfer of wealth—stands eviscerated by a combination of cuts and the refusal of Congress to shut down avoidance strategies that tax lawyers have fine-tuned and court decisions have blessed.

Today, even billionaires can avoid federal estate and gift tax entirely.

Here’s how undertaxed our billionaires have become: In a study commissioned by the U.S. Treasury Department, four economists at the University of California-Berkeley analyzed the tax payments of the richest 0.001% of American tax units, about 380 taxpayers in all, a total that roughly matches the annual Forbes 400.

In 2019, this study found, those 380 deep pockets ended up paying in taxes federal, state, and foreign just 2% of their wealth. The average tax burden between 2018 and 2020 for those in the top 0.00005%—some 90 tax units—amounted to just 1% of their wealth.

Meanwhile, between 2014 and 2024, the total wealth of the Forbes 400 grew from $2.3 trillion to $5.4 trillion, an average annual growth rate, net of taxes and consumption spending, of 8.9%. The wealth of just the top 19 on the Forbes list over these years grew at an annual rate of over 12%.

So do the math: Oligarchic wealth in America is growing at a rate that dwarfs the actual tax rate upon that wealth. The oligarchic cancer destroying American democracy is continuing—and will continue—to metastasize.

Unless we rise up.