The story is worse than people think. Now that the government has been forced to disclose the full legal advice submitted by Lord Goldsmith, the extent to which Parliament and the country were misled is clear for all to see.

The issue at stake is not whether, when or why the Attorney General changed his mind on the legality of war in Iraq. Tony Blair and Jack Straw have pointed out, with the customary slipperiness of a profession they know well, that it is the right of a lawyer to elide from one line of argument to the next. Goldsmith's views may well have "evolved". In fact, I have previously documented how they did.

What matters is that MPs were not made aware of - to put it politely - the progression of his thinking. When Goldsmith sat in the cabinet seat vacated hours earlier by Robin Cook, he was asked by the Prime Minister to make a presentation of the legal case for invasion. Blair did not invite questions before the Attorney was thanked for his contribution and left.

Later that day, 17 March 2003, the House of Lords received a document entitled "the attorney-general's view of the legal basis for the use of force against Iraq". Straw published a similar paper in the Commons. These papers were of an entirely different nature to the legal advice of 7 March that the government has sought so hard to keep secret. They were not, as some ministers claimed, a "summary" of the legal advice. These were papers of advocacy - partial, tendentious accounts of that advice, shorn of the caveats that Goldsmith had included 10 days earlier. Sexing up had become a habit. If MPs had been given the full information, they might have concluded differently. Too much impartial knowledge, in Blair's world, is dangerous.

Goldsmith's U-turn came as a surprise to the legal establishment and to Whitehall. A commercial barrister with little experience of international law, he shifted his position on the legality of war not once, but twice. Between September 2002 and February 2003 the Attorney let it be known, usually verbally, that he could not sanction military action without specific UN approval. He indicated that resolution 1441 did not provide that automatic trigger and that a further resolution was necessary.

Goldsmith's team worked closely with the Foreign Office lawyers, who were unanimously concerned about the legality of the impending war. Crucially, he told them they knew what his view was but added that he could not give them a formal steer. The implication was that Blair would not let him. If at any point during this period Goldsmith had disagreed with the FCO legal opinion he had ample opportunity to tell them.

Blair was fully aware of his attorney's reservations. For that reason he instructed him not to declare his position formally. When challenged by one cabinet minister in autumn 2002 why the Government had not yet received formal advice from Goldsmith, Blair responded: "I'll ask him when I have to, and not before."

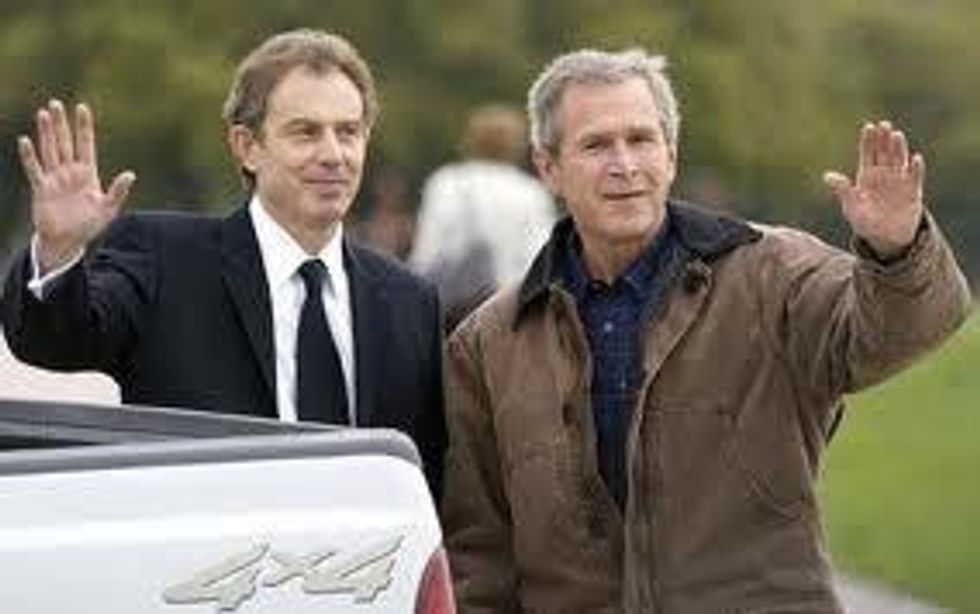

In mid-February, Goldsmith was instructed to go to Washington. There he met not just his US counterpart, John Ashcroft, but a powerful behind-the-scenes figure called John Bellinger. He was sent, in the words of one official, "to put some steel in his spine". Even then he could not bring himself to produce the unequivocal endorsement that Blair and George Bush required. Goldsmith told lawyer friends in the fraught final weeks before war that his position was impossible. He wondered out loud whether he should stay. He did the business, and did stay.

So sensitive is the whole affair that Goldsmith was reluctant to speak about it during his two appearances before the Butler inquiry a year ago. His testimony was regarded as evasive and unconvincing. Initially he even suggested that he could not show the 7 March advice. The five-person committee was flabbergasted. Goldsmith acceded to their demand only after they told him they would abandon their inquiry and announce why they had done so. That would have precipitated another crisis.

When asked by Butler why he had refused to circulate to senior ministers or to the Permanent Secretaries of key government departments the doubt-laden 7 March document, Blair suggested he could not trust some members of his cabinet with such papers. Again, Lord Butler and his team were taken aback by the audacity.

As with weapons of mass destruction, there is no need to accuse Blair of outright lies. The chronology of events speaks for itself. He committed himself to war at Bush's ranch in April 2002. From that point he was in a bind. He had to make the facts fit. These were actions of a desperate man, who blundered into one of the worst foreign policy decisions of modern times. He bought time for himself, but in so doing lost our trust.