In late May, I went to Georgia, where I met with Troy Anthony Davis on Death Row. He has been there for eighteen years, and I wanted to speak with him. I came away convinced that he represents the most compelling case of innocence in decades.

This week, the Supreme Court agreed to decide whether to hear the request for a writ of habeas corpus in Davis's case in September hopefully signaling a more careful review of his motion. The reality, though, is that the last time the Justices granted such a motion was 1925 and should the Supreme Court decline the request, the countdown to Davis's execution will begin. It is even more imperative that the Chatham County District Attorney, Larry Chisolm, act now to do the right thing, and move to reopen the case.

The case must be reopened for several reasons: Davis's conviction was based on the word of eyewitnesses. However, since 2001, seven of the nine witnesses recanted or contradicted their original testimony. Several said they were coerced by the police. No physical evidence was ever produced that tied Davis to the murder of Mark Allen MacPhail, a white off-duty Savannah police officer who was killed as he tried to break up a street fight. The gun used in the shooting was never found.

Second, there is abundant evidence supporting Davis's likely innocence but it has not been aired in court. Our legal system does not allow defendants the opportunity to present new evidence of their innocence after conviction. This intransigence on legal procedural matters is unconscionable when a life is on the line.

The new evidence of his innocence means Davis deserves another day in court, not execution: The prospect that an innocent man might be put to death based on faulty witness testimony, and because the court won't agree to hear evidence of his innocence, represents a tragedy of epic proportions. A wrongful execution cannot be rectified.

More than thirty years' worth of social science and criminal justice research shows that eyewitness testimonies are notoriously unreliable, according to The Innocence Project. Since 1973, a total of 133 men and women have been exonerated or had their death sentences commuted based on post-conviction findings that demonstrated their likely innocence, according to the Death Penalty Information Center.

Adding to the sense of urgency around the Davis case, too, is the long, sour history of wrongly-accused black men receiving "rough justice" in the Deep South. Davis was convicted in Chatham County, a place where genteel traditions and picturesque antebellum mansions mask the harsher truths about the history of slavery, racism, and the Jim Crow era that is still imprinted on the region. Chatham County is home to about 250,000 of Georgia's 9.7 million residents but it has produced 40 percent of all death row exonerations in the state.

The department of corrections in Georgia has blocked television media from visiting Davis. But when I met with him on May 29, I was overwhelmed by his quiet confidence, and by the high regard with which he is held by inmates and personnel alike.

It is evident that Davis's jailers--prison guards whose faces are usually stony or a blank slate of indifference--are moved by his plight. While we talked, I saw guards who clearly had come to believe as I do--that Troy Davis has spent nearly half his life on Death Row for a crime he did not commit. Outside, as I crossed the parking-lot under a merciless sun, I chatted with a woman who said she knew of a former guard who quit his duty at that facility, rather than have to take part in marching Troy Davis to the death chamber. I share that man's sense of outrage. I've also met with Davis's sister, Marita, and her son. He is nearing adulthood, and has only known his uncle as a Death Row inmate. But Davis, a former athletic coach, has nonetheless been an effective, compassionate mentor to his only nephew.

Yet it is not only the many details of Davis's humanity that has led to a groundswell of grassroots support for a campaign to reopen the case: It is the undeniable fact that, as a nation of laws, we have an obligation to reconsider death penalty convictions when new evidence of innocence is revealed.

This is why a "strange bedfellows" group of individuals have been drawn together to fight for the reopening of his case, including former FBI Director William Sessions, Pope Benedict XVI; former Libertarian Party presidential candidate Bob Barr, and Archbishop Desmond Tutu. Sessions, in fact, has been quite fired up about the need for reforms in a court and criminal justice system that refuses to re-examine a death penalty case despite new evidence that may prove a defendant's innocence.

"Only a full hearing, with all witnesses subject to rigorous cross-examination and a full exploration of the circumstances of their testimony, will provide a means to determine the reliability of the conviction," Sessions wrote in an Atlanta Journal-Constitution op-ed last year. "This never happened at [Troy Davis] trial. It must happen now."

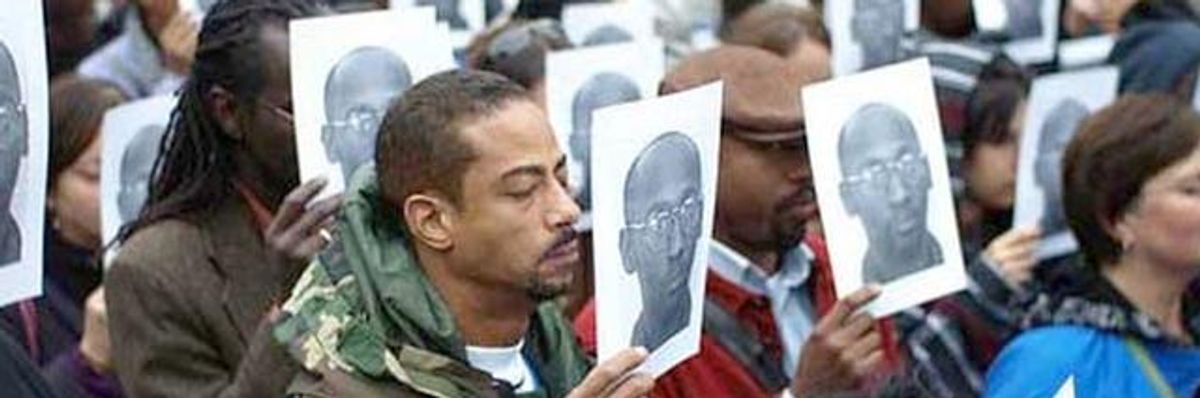

The idea that any American might be sentenced to death without being allowed a full airing of all the evidence is an outrage, and represents a blatant flouting of our nation's founding principles. The NAACP has joined with Sessions, former president Jimmy Carter; Amnesty International, and a coalition of other human and civil rights groups to raise awareness of not only just the Troy Davis case, but of the urgent need to push for reforms to the criminal justice system. At www.iamtroy.com, information is available showing why innocence matters, and how all Americans can become a part of the movement to find solutions.

I believe that Troy Davis is innocent--and that the family of the slain Savannah police officer, Mark MacPhail, deserve to see the real killer brought to justice. These two things are not mutually exclusive, and our Constitution should be strong enough to ensure that both parts of that equation are realized.