The Deepwater Horizon drilling rig exploded off the coast of Louisiana one year ago, killing 11 crewmembers and ultimately releasing some 210 million gallons of oil. It became the largest oil disaster in American history. It could happen again.

Keith Jones didn't need to wait for the phone call. He knew the moment he saw the images of the April 20, 2010 explosion on television that his son was dead. Gordon, age 28, had a two-year-old son and a pregnant wife, Michelle, eagerly waiting for him at home. He was on the rig for just a one-week tour before heading home for the birth of his second child. Had he not volunteered to stay on for an extra shift because his coworker was tired, he might have made it home.

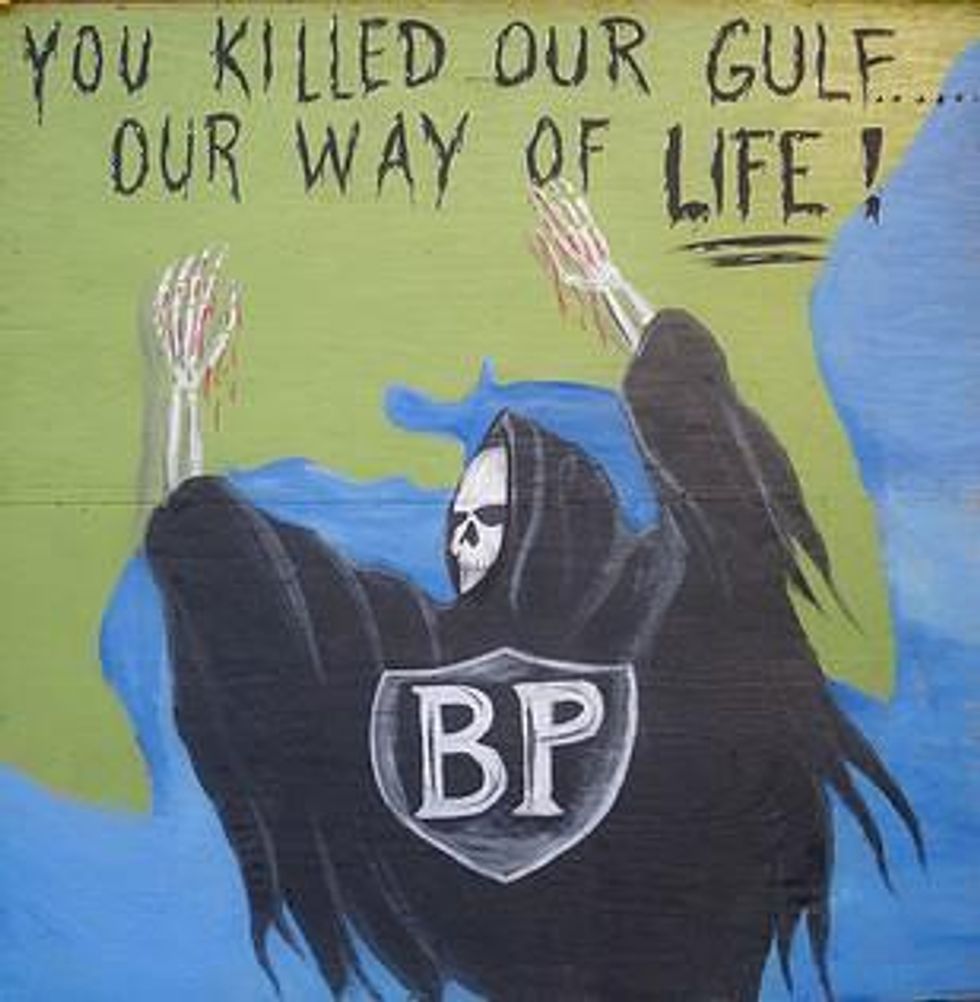

On that April day, BP lost a game of chicken it had long played with the Macondo oil well. Dubbed the "Well from Hell," the oil buried 18,500 feet below the ocean's surface had made it clear time and again that it had no intention of being pumped out of the earth. But BP refused to listen.

BP wasn't alone. Government regulators, playing out their overly intimate and trusting relationship with the oil industry, rubber-stamped every cost-cutting and progressively deadly decision. Transocean, the largest operator of oil and gas rigs in the world, and Halliburton, the world's largest energy services company, among others, operated with failed--and possibly criminal--procedures.

It was only after the explosion and the heart-rending stream of photos of oil-soaked birds that we all learned a terrible secret: although every major oil company operating in deep water around the world had guaranteed that it could handle a blowout, not a single one knew what to do. Instead, the industry's supposed emergency-response experts spent three long months learning on the fly, applying shallow-water technology suitable for wells at 400 or less feet below the ocean's surface to a deepwater blowout 5,000 feet below the surface.

Five months and nearly 5 million barrels of oil later, a newly drilled relief well finally sealed Macondo's gusher. There is no way to speed the drilling of such a well. Thus, if another deepwater blowout occurs, it is all but guaranteed that another massive release of oil is in our future.

Although each major oil company operating in the Gulf had certified that it could handle a gusher of 300,000 barrels of oil per day, none could. At its worst, the Macondo well released 80,000 barrels of oil per day. Yet no company had ships that could hold even a fraction of that oil, adequate booms to contain it, or adequate skimmers to suck it up.

Instead, in a case of the cure being worse than the disease, nearly 2 million gallons of toxic chemical dispersants were simultaneously mixed into the water and sprayed from the air to break the oil up, while at least 410 fires were ignited on the water's surface to burn the oil away. For those living in, on, and from the water, the impacts of the oil, dispersants, and fires are profound and ongoing.

The Deepwater Horizon tragedy isn't over. Oil and dispersants still line the bottom of the ocean, waiting for the next wave or hurricane to wash them ashore. What's not on the ocean floor is the sea life that once abounded there. Missing from the waters are the baby oysters and shrimp on which the fishers' 'livelihoods depend. The ocean continues to wash up dead fish, dolphins, and other sea life. Oily tar balls still dot the beaches. Local residents still suffer "the BP cough."

And the local economy has yet to recover. A mere 40 percent of the claims filed for those economically harmed by the disaster have even been processed, much less paid.

A few months after the explosion, Keith Jones told me that when his older grandson started talking in full sentences, he asked the question he'd held in his head all along: "Where is my daddy?"

On the BP oil disaster's one-year anniversary, it's time to learn its most important lesson: deepwater drilling isn't safe or worth the risk.