Rabindranath Tagore: Much More Than a Mystic

Canada must believe in great ideals. She will have to solve . . . the most difficult of all problems, the race problem.

-- Rabindranath Tagore, Vancouver, 1929

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Canada must believe in great ideals. She will have to solve . . . the most difficult of all problems, the race problem.

-- Rabindranath Tagore, Vancouver, 1929

Canada must believe in great ideals. She will have to solve . . . the most difficult of all problems, the race problem.

-- Rabindranath Tagore, Vancouver, 1929

Few Canadians know of him today but thousands of Canadians did 80 years ago, turning out in droves to see and hear Rabindranath Tagore, the first non-European Nobel laureate (Literature, 1913), and Asia's iconic poet and humanist whose 150th birth anniversary fell on May 7. The event was celebrated widely, including in Toronto and, very appropriately, in Vancouver, which he visited in 1929. He went there after having declined several invitations in protest against the Komagata Maru incident of 1914, when 376 Indian immigrants were denied entry to Canada.

Tagore was larger than life: a poet, philosopher, playwright, novelist, essayist, painter, composer and educator. He gave both India and Bangladesh their national anthems. Tagore drew a huge following wherever he went: China, Japan, Latin America, Europe and the United States. In China, Tagore remains the most widely translated foreign author after Shakespeare.

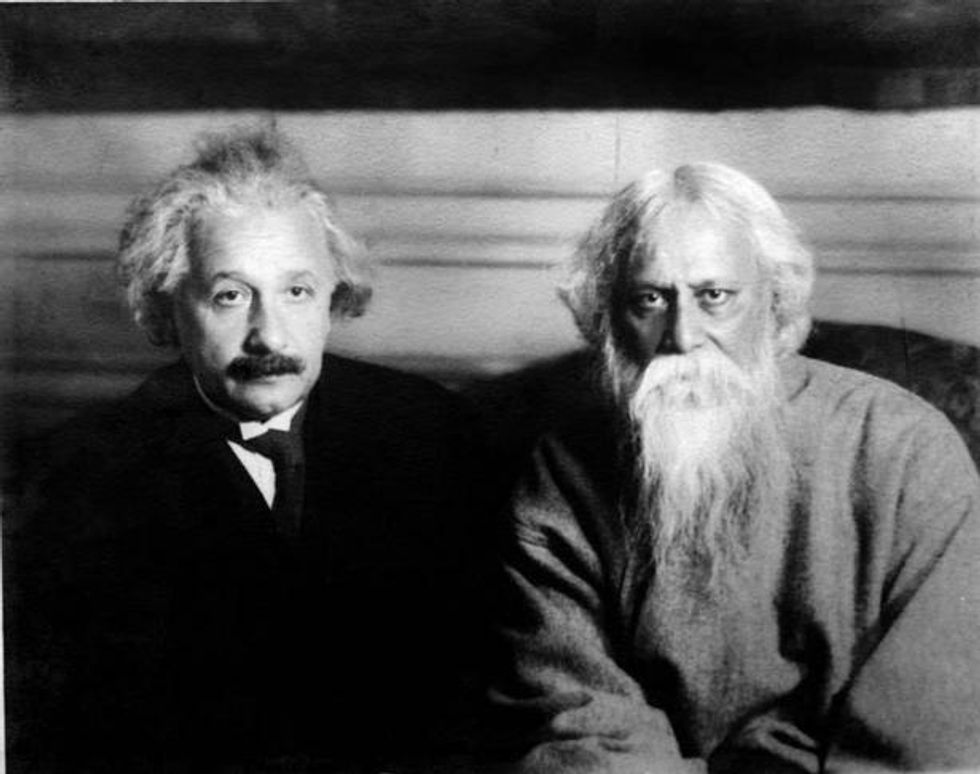

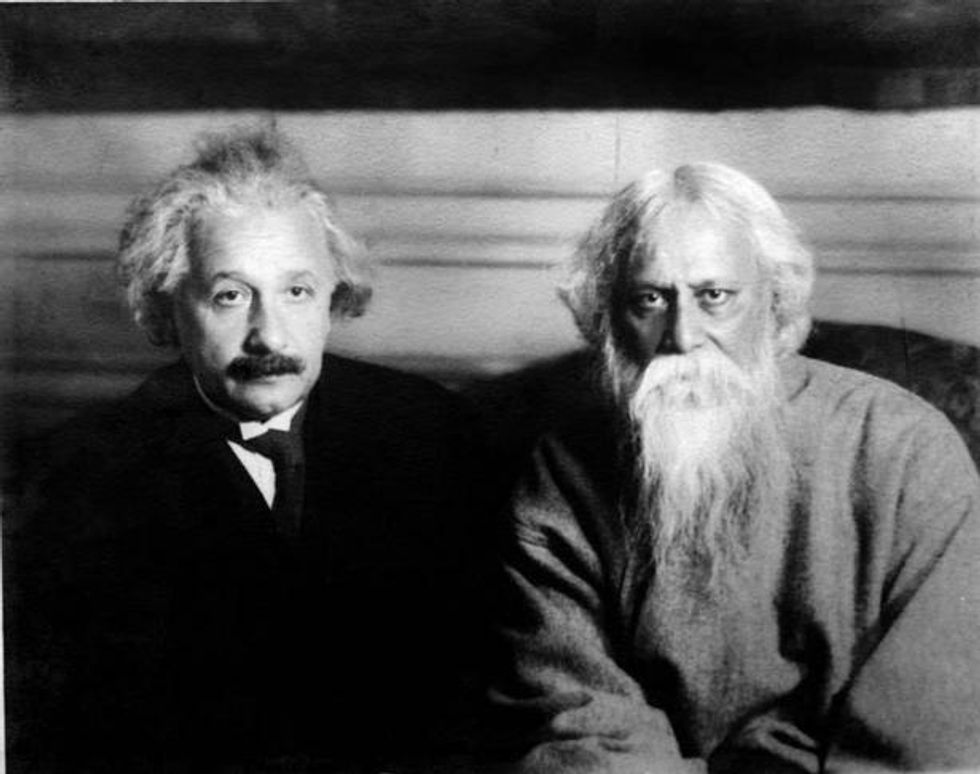

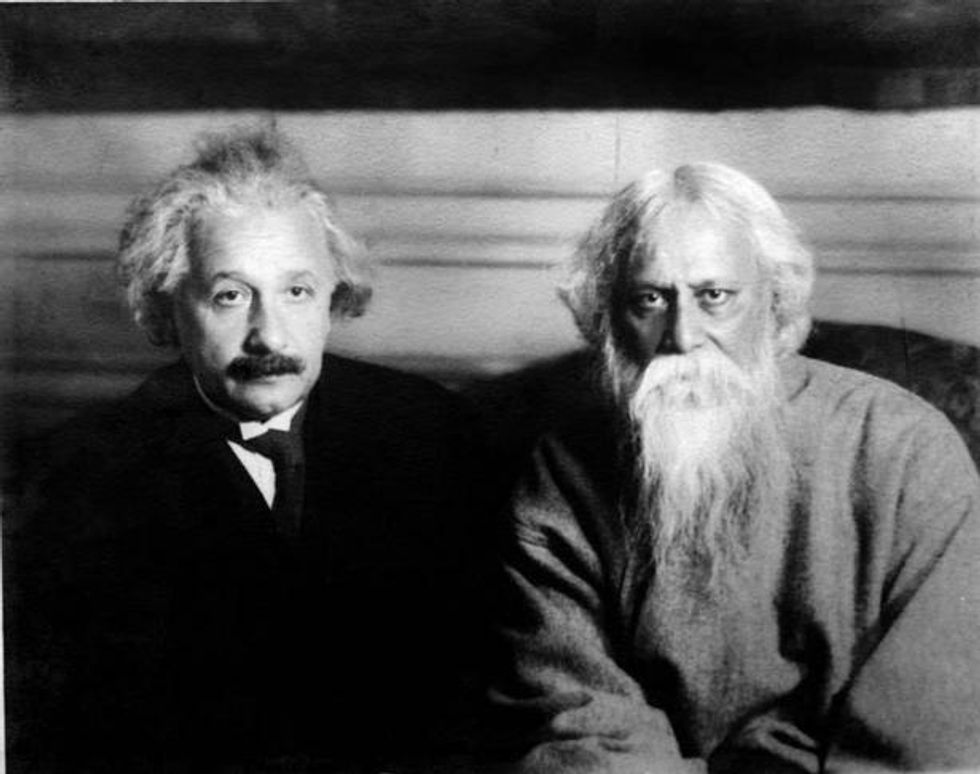

Among those who interacted with him were Albert Einstein and W.B. Yeats, the Nobel laureate poet, who wrote that Tagore's poetry stirred his blood "as nothing had for years." Einstein and Tagore conversed about many things -- from the nature of reality to music -- and were joint signatories to an antiwar letter in 1919. Tagore inspired such leaders as Mahatma Gandhi, his contemporary, and later Aung San Suu Kyi. As Myanmar's Peace laureate wrote in 2001, her "most precious lesson" had been from Tagore: "If no one answers your call, walk alone."

To the West, however, Tagore remained the "Eastern mystic," acclaimed during his lifetime and then forgotten. But more than a mystic, Tagore was a visionary who articulated ideals of humanism, equality and freedom long before the League of Nations or the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948. Disproving the claim that such ideas must necessarily come from the "West," Tagore showed how they existed in the folk philosophies of the East and in different religions, such as Buddhism and Islam. This was the theme of his Oxford University lectures in 1930.

Tagore was also one of the strongest critics of war and colonialism, fascism, and the dangers of narrow-minded nationalism. In the 1920s, he had already identified race as the greatest problem in a fast globalizing world.

Tagore rejected the notion that knowledge (and civilization) must flow from the West to the East. The West and the East had much to learn from each other, he contended, but colonialism made that impossible. Colonial education was like "education of the prison-house," intended to "produce carriers of the white man's burden . . . The training we get" tells us "that it is not for us to produce but to borrow."

In 1921 Tagore established Visva Bharati, the "world university," to bring East and West together as equals, undaunted by the asymmetry of power. Scholars, artists and students came from Europe, China, Japan, Java, Burma, Sri Lanka, Afghanistan and Palestine. A true exchange of knowledge and culture prospered at Visva Bharati.

Tagore was prophetic in his understanding of India's development. He deeply lamented the coexistence of urban prosperity and rural decay, a problem that still haunts India. "Our villages are dying," he wrote. The indifference of the urban educated classes tormented him immensely. He established a program of rural reconstruction, which anticipated by a century the notions of people-centred development so popular today.

The world has yet to fully appreciate Tagore's vision. Our youth, if they knew him, would deeply value his message of freeing creativity from every form of domination. This year's celebrations offer wonderful opportunities to know Tagore: a Tagore Festival takes place at the Etobicoke School of Arts on June 25-26; a Tagore Fair; a film festival, an exhibit of Tagore's life, and a creative competition for Canadian youth (see tagore150toronto.ca). York University is planning Echoes of Tagore, an event that will explore Tagore's influence in the Muslim world.

These celebrations in Canada, organized mostly by South Asians, perhaps have a message for all Canadians.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

Canada must believe in great ideals. She will have to solve . . . the most difficult of all problems, the race problem.

-- Rabindranath Tagore, Vancouver, 1929

Few Canadians know of him today but thousands of Canadians did 80 years ago, turning out in droves to see and hear Rabindranath Tagore, the first non-European Nobel laureate (Literature, 1913), and Asia's iconic poet and humanist whose 150th birth anniversary fell on May 7. The event was celebrated widely, including in Toronto and, very appropriately, in Vancouver, which he visited in 1929. He went there after having declined several invitations in protest against the Komagata Maru incident of 1914, when 376 Indian immigrants were denied entry to Canada.

Tagore was larger than life: a poet, philosopher, playwright, novelist, essayist, painter, composer and educator. He gave both India and Bangladesh their national anthems. Tagore drew a huge following wherever he went: China, Japan, Latin America, Europe and the United States. In China, Tagore remains the most widely translated foreign author after Shakespeare.

Among those who interacted with him were Albert Einstein and W.B. Yeats, the Nobel laureate poet, who wrote that Tagore's poetry stirred his blood "as nothing had for years." Einstein and Tagore conversed about many things -- from the nature of reality to music -- and were joint signatories to an antiwar letter in 1919. Tagore inspired such leaders as Mahatma Gandhi, his contemporary, and later Aung San Suu Kyi. As Myanmar's Peace laureate wrote in 2001, her "most precious lesson" had been from Tagore: "If no one answers your call, walk alone."

To the West, however, Tagore remained the "Eastern mystic," acclaimed during his lifetime and then forgotten. But more than a mystic, Tagore was a visionary who articulated ideals of humanism, equality and freedom long before the League of Nations or the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948. Disproving the claim that such ideas must necessarily come from the "West," Tagore showed how they existed in the folk philosophies of the East and in different religions, such as Buddhism and Islam. This was the theme of his Oxford University lectures in 1930.

Tagore was also one of the strongest critics of war and colonialism, fascism, and the dangers of narrow-minded nationalism. In the 1920s, he had already identified race as the greatest problem in a fast globalizing world.

Tagore rejected the notion that knowledge (and civilization) must flow from the West to the East. The West and the East had much to learn from each other, he contended, but colonialism made that impossible. Colonial education was like "education of the prison-house," intended to "produce carriers of the white man's burden . . . The training we get" tells us "that it is not for us to produce but to borrow."

In 1921 Tagore established Visva Bharati, the "world university," to bring East and West together as equals, undaunted by the asymmetry of power. Scholars, artists and students came from Europe, China, Japan, Java, Burma, Sri Lanka, Afghanistan and Palestine. A true exchange of knowledge and culture prospered at Visva Bharati.

Tagore was prophetic in his understanding of India's development. He deeply lamented the coexistence of urban prosperity and rural decay, a problem that still haunts India. "Our villages are dying," he wrote. The indifference of the urban educated classes tormented him immensely. He established a program of rural reconstruction, which anticipated by a century the notions of people-centred development so popular today.

The world has yet to fully appreciate Tagore's vision. Our youth, if they knew him, would deeply value his message of freeing creativity from every form of domination. This year's celebrations offer wonderful opportunities to know Tagore: a Tagore Festival takes place at the Etobicoke School of Arts on June 25-26; a Tagore Fair; a film festival, an exhibit of Tagore's life, and a creative competition for Canadian youth (see tagore150toronto.ca). York University is planning Echoes of Tagore, an event that will explore Tagore's influence in the Muslim world.

These celebrations in Canada, organized mostly by South Asians, perhaps have a message for all Canadians.

Canada must believe in great ideals. She will have to solve . . . the most difficult of all problems, the race problem.

-- Rabindranath Tagore, Vancouver, 1929

Few Canadians know of him today but thousands of Canadians did 80 years ago, turning out in droves to see and hear Rabindranath Tagore, the first non-European Nobel laureate (Literature, 1913), and Asia's iconic poet and humanist whose 150th birth anniversary fell on May 7. The event was celebrated widely, including in Toronto and, very appropriately, in Vancouver, which he visited in 1929. He went there after having declined several invitations in protest against the Komagata Maru incident of 1914, when 376 Indian immigrants were denied entry to Canada.

Tagore was larger than life: a poet, philosopher, playwright, novelist, essayist, painter, composer and educator. He gave both India and Bangladesh their national anthems. Tagore drew a huge following wherever he went: China, Japan, Latin America, Europe and the United States. In China, Tagore remains the most widely translated foreign author after Shakespeare.

Among those who interacted with him were Albert Einstein and W.B. Yeats, the Nobel laureate poet, who wrote that Tagore's poetry stirred his blood "as nothing had for years." Einstein and Tagore conversed about many things -- from the nature of reality to music -- and were joint signatories to an antiwar letter in 1919. Tagore inspired such leaders as Mahatma Gandhi, his contemporary, and later Aung San Suu Kyi. As Myanmar's Peace laureate wrote in 2001, her "most precious lesson" had been from Tagore: "If no one answers your call, walk alone."

To the West, however, Tagore remained the "Eastern mystic," acclaimed during his lifetime and then forgotten. But more than a mystic, Tagore was a visionary who articulated ideals of humanism, equality and freedom long before the League of Nations or the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948. Disproving the claim that such ideas must necessarily come from the "West," Tagore showed how they existed in the folk philosophies of the East and in different religions, such as Buddhism and Islam. This was the theme of his Oxford University lectures in 1930.

Tagore was also one of the strongest critics of war and colonialism, fascism, and the dangers of narrow-minded nationalism. In the 1920s, he had already identified race as the greatest problem in a fast globalizing world.

Tagore rejected the notion that knowledge (and civilization) must flow from the West to the East. The West and the East had much to learn from each other, he contended, but colonialism made that impossible. Colonial education was like "education of the prison-house," intended to "produce carriers of the white man's burden . . . The training we get" tells us "that it is not for us to produce but to borrow."

In 1921 Tagore established Visva Bharati, the "world university," to bring East and West together as equals, undaunted by the asymmetry of power. Scholars, artists and students came from Europe, China, Japan, Java, Burma, Sri Lanka, Afghanistan and Palestine. A true exchange of knowledge and culture prospered at Visva Bharati.

Tagore was prophetic in his understanding of India's development. He deeply lamented the coexistence of urban prosperity and rural decay, a problem that still haunts India. "Our villages are dying," he wrote. The indifference of the urban educated classes tormented him immensely. He established a program of rural reconstruction, which anticipated by a century the notions of people-centred development so popular today.

The world has yet to fully appreciate Tagore's vision. Our youth, if they knew him, would deeply value his message of freeing creativity from every form of domination. This year's celebrations offer wonderful opportunities to know Tagore: a Tagore Festival takes place at the Etobicoke School of Arts on June 25-26; a Tagore Fair; a film festival, an exhibit of Tagore's life, and a creative competition for Canadian youth (see tagore150toronto.ca). York University is planning Echoes of Tagore, an event that will explore Tagore's influence in the Muslim world.

These celebrations in Canada, organized mostly by South Asians, perhaps have a message for all Canadians.