SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

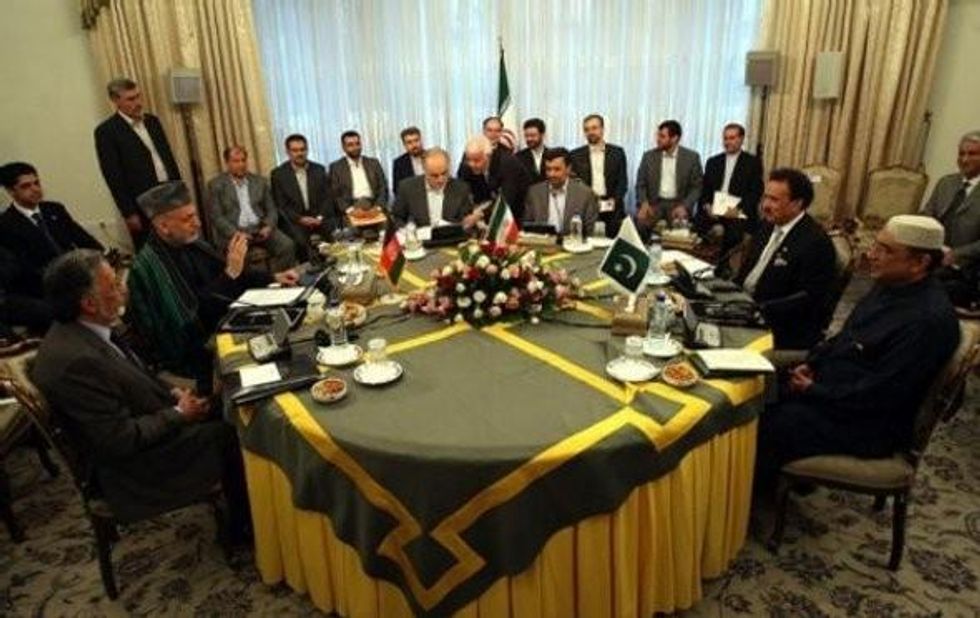

What is wrong with this picture?

After all, it looks like a typical photo of world leaders making decisions for their countries. That is precisely the problem. What's wrong is the total absence of women--at the table, in the room, and, as a result, from the agenda at this meeting and too many meetings like it.

What is wrong with this picture?

After all, it looks like a typical photo of world leaders making decisions for their countries. That is precisely the problem. What's wrong is the total absence of women--at the table, in the room, and, as a result, from the agenda at this meeting and too many meetings like it.

I worked with the United Nations in Afghanistan from 2008 to 2010 with women human rights defenders. Since coming back to the US, I am aware of the urgency in public calls to end our military involvement in Afghanistan, which means increasing pressure to negotiate with the Taliban for a political power sharing deal. Yet, I also hear in the back of my head the voices of Afghan women, who have warned all along, Don't wager human rights, especially the fragile ones of women, for the sake of political expediency in striking a peace deal.

The photo portrays a three-way summit on June 24 hosted by Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad with Pakistani President Asif Ali Zardari and his Afghan counterpart, President Hamid Karzai. The goal of the meeting was to discuss "concern over a rising lack of security, extremism and terrorism," and the need for "cooperation to combat these phenomena." The day following the photo, Presidents Zardari and Karzai attended an international anti-terrorism conference, again hosted by Ahmadinejad. Also present was Sudan's President Omar al-Bashir, wanted by the International Criminal Court on charges of war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide in Darfur, where rape was used rampantly as a weapon of war.

As the Obama administration and President Karzai's government undertake talks-about-talks to engage the Taliban, how many women will be at that table? Afghan women have expressed concerns that "behind the scenes" peace deals are already taking place. While women have fought to be included in public processes (they hold 9 of the 70 seats of the Afghanistan High Peace Council put together by Karzai last year), they are consistently locked out of the "old boy networks" of male world leaders where decisions are being made that will have vital consequences on the lives of women and their families. That is the problem the photo makes clear. Right now, the Afghanistan peace process is proceeding without the participation of women.

In 2000, the UN Security Council unanimously adopted Resolution 1325, obliging all UN member states to promote and protect women's meaningful participation in peace and security processes. Yet, UN Women's research has found that in 24 peace processes over the past two decades, women formed less than 8 percent of negotiating teams--and, as a result, women's needs and concerns are almost entirely missing from the resulting agreements. A study of 585 peace agreements concluded between 1990 and 2010 found that just 16 percent referred to women at all--only 3 percent had a reference to sexual- or gender-based violence.

When women are at the table, their concerns are more likely to be addressed. Their perspectives on human needs, peacebuilding, and reconciliation can be included. Their experiences can add to the understanding of the impact of war and everyday violence in communities, homes, and families--and therefore increase the likelihood of an authentic, lasting, and just peace.

Afghan women have been making this argument for years. Last week, 11 women human rights leaders were in Washington DC to meet with policy makers at the White House and in Congress. They pushed for the inclusion of more women leaders in peace talks to end the war in their country. They insisted that they are capable of contributing despite real--and at times tragic--risks to women who enter public life in Afghanistan.

The women repeated their message on PBS NewsHour a day before President Obama announced an accelerated withdrawal of troops from Afghanistan. None of the women rejected negotiations with the Taliban out of hand--indeed, they suggest that such direct dialogue could be beneficial. Yet, they pointed to a situation more complicated than simply talking to the Taliban when it comes to the security for Afghan women. Wazhma Frogh, from the Afghan Women's Network, said:

[the] Taliban are not the only threats to the women of Afghanistan or to all the people of Afghanistan. I have seen warlords who have raped women on the streets. We have seen people who have taken our lands. We have seen people who have done more damage.

Frogh also explained how people are driven to insurgency by the Afghan government itself:

It has no capacity in providing people with access to justice. So, a 13-year-old girl raped with 13 police, 13 men which--police officers among them, what do you expect people--like, the father of that girl says, I will blow myself up in a suicide attack, blowing up a government entity.

Negotiation tables most often include armed actors, who may be able to end the war but are little-equipped to bring the peace. As long as peace talks privilege those with arms--and those who derive their power from armed conflict--women and other nonviolent members of civil society will be excluded. The resulting "peace" deal too often redistributes power among a small group of armed actors, rather than creating a sustainable process that can establish a society based on justice, accountability, and inclusivity. History has shown that the end result is a recurring cycle of violence. Rangina Hamidi, a peace activist from Kandahar, spoke on PBS NewsHour about the tenuous gains Afghan women have made in the past ten years. She appeals:

Please, do not let Afghanistan fall back to the years of civil war, to the years of injustice and inhuman acts against all sectors of society, most especially women. So, for once, let's listen to the women and take their suggestions seriously.

As the US and Europe scramble for an exit strategy out of Afghanistan, they will need a way to claim relative success after 10 years of war. Isn't it time to look to Afghan women as agents of change and brokers of authentic human security? Peace requires this, and Afghanistan deserves this.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

What is wrong with this picture?

After all, it looks like a typical photo of world leaders making decisions for their countries. That is precisely the problem. What's wrong is the total absence of women--at the table, in the room, and, as a result, from the agenda at this meeting and too many meetings like it.

I worked with the United Nations in Afghanistan from 2008 to 2010 with women human rights defenders. Since coming back to the US, I am aware of the urgency in public calls to end our military involvement in Afghanistan, which means increasing pressure to negotiate with the Taliban for a political power sharing deal. Yet, I also hear in the back of my head the voices of Afghan women, who have warned all along, Don't wager human rights, especially the fragile ones of women, for the sake of political expediency in striking a peace deal.

The photo portrays a three-way summit on June 24 hosted by Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad with Pakistani President Asif Ali Zardari and his Afghan counterpart, President Hamid Karzai. The goal of the meeting was to discuss "concern over a rising lack of security, extremism and terrorism," and the need for "cooperation to combat these phenomena." The day following the photo, Presidents Zardari and Karzai attended an international anti-terrorism conference, again hosted by Ahmadinejad. Also present was Sudan's President Omar al-Bashir, wanted by the International Criminal Court on charges of war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide in Darfur, where rape was used rampantly as a weapon of war.

As the Obama administration and President Karzai's government undertake talks-about-talks to engage the Taliban, how many women will be at that table? Afghan women have expressed concerns that "behind the scenes" peace deals are already taking place. While women have fought to be included in public processes (they hold 9 of the 70 seats of the Afghanistan High Peace Council put together by Karzai last year), they are consistently locked out of the "old boy networks" of male world leaders where decisions are being made that will have vital consequences on the lives of women and their families. That is the problem the photo makes clear. Right now, the Afghanistan peace process is proceeding without the participation of women.

In 2000, the UN Security Council unanimously adopted Resolution 1325, obliging all UN member states to promote and protect women's meaningful participation in peace and security processes. Yet, UN Women's research has found that in 24 peace processes over the past two decades, women formed less than 8 percent of negotiating teams--and, as a result, women's needs and concerns are almost entirely missing from the resulting agreements. A study of 585 peace agreements concluded between 1990 and 2010 found that just 16 percent referred to women at all--only 3 percent had a reference to sexual- or gender-based violence.

When women are at the table, their concerns are more likely to be addressed. Their perspectives on human needs, peacebuilding, and reconciliation can be included. Their experiences can add to the understanding of the impact of war and everyday violence in communities, homes, and families--and therefore increase the likelihood of an authentic, lasting, and just peace.

Afghan women have been making this argument for years. Last week, 11 women human rights leaders were in Washington DC to meet with policy makers at the White House and in Congress. They pushed for the inclusion of more women leaders in peace talks to end the war in their country. They insisted that they are capable of contributing despite real--and at times tragic--risks to women who enter public life in Afghanistan.

The women repeated their message on PBS NewsHour a day before President Obama announced an accelerated withdrawal of troops from Afghanistan. None of the women rejected negotiations with the Taliban out of hand--indeed, they suggest that such direct dialogue could be beneficial. Yet, they pointed to a situation more complicated than simply talking to the Taliban when it comes to the security for Afghan women. Wazhma Frogh, from the Afghan Women's Network, said:

[the] Taliban are not the only threats to the women of Afghanistan or to all the people of Afghanistan. I have seen warlords who have raped women on the streets. We have seen people who have taken our lands. We have seen people who have done more damage.

Frogh also explained how people are driven to insurgency by the Afghan government itself:

It has no capacity in providing people with access to justice. So, a 13-year-old girl raped with 13 police, 13 men which--police officers among them, what do you expect people--like, the father of that girl says, I will blow myself up in a suicide attack, blowing up a government entity.

Negotiation tables most often include armed actors, who may be able to end the war but are little-equipped to bring the peace. As long as peace talks privilege those with arms--and those who derive their power from armed conflict--women and other nonviolent members of civil society will be excluded. The resulting "peace" deal too often redistributes power among a small group of armed actors, rather than creating a sustainable process that can establish a society based on justice, accountability, and inclusivity. History has shown that the end result is a recurring cycle of violence. Rangina Hamidi, a peace activist from Kandahar, spoke on PBS NewsHour about the tenuous gains Afghan women have made in the past ten years. She appeals:

Please, do not let Afghanistan fall back to the years of civil war, to the years of injustice and inhuman acts against all sectors of society, most especially women. So, for once, let's listen to the women and take their suggestions seriously.

As the US and Europe scramble for an exit strategy out of Afghanistan, they will need a way to claim relative success after 10 years of war. Isn't it time to look to Afghan women as agents of change and brokers of authentic human security? Peace requires this, and Afghanistan deserves this.

What is wrong with this picture?

After all, it looks like a typical photo of world leaders making decisions for their countries. That is precisely the problem. What's wrong is the total absence of women--at the table, in the room, and, as a result, from the agenda at this meeting and too many meetings like it.

I worked with the United Nations in Afghanistan from 2008 to 2010 with women human rights defenders. Since coming back to the US, I am aware of the urgency in public calls to end our military involvement in Afghanistan, which means increasing pressure to negotiate with the Taliban for a political power sharing deal. Yet, I also hear in the back of my head the voices of Afghan women, who have warned all along, Don't wager human rights, especially the fragile ones of women, for the sake of political expediency in striking a peace deal.

The photo portrays a three-way summit on June 24 hosted by Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad with Pakistani President Asif Ali Zardari and his Afghan counterpart, President Hamid Karzai. The goal of the meeting was to discuss "concern over a rising lack of security, extremism and terrorism," and the need for "cooperation to combat these phenomena." The day following the photo, Presidents Zardari and Karzai attended an international anti-terrorism conference, again hosted by Ahmadinejad. Also present was Sudan's President Omar al-Bashir, wanted by the International Criminal Court on charges of war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide in Darfur, where rape was used rampantly as a weapon of war.

As the Obama administration and President Karzai's government undertake talks-about-talks to engage the Taliban, how many women will be at that table? Afghan women have expressed concerns that "behind the scenes" peace deals are already taking place. While women have fought to be included in public processes (they hold 9 of the 70 seats of the Afghanistan High Peace Council put together by Karzai last year), they are consistently locked out of the "old boy networks" of male world leaders where decisions are being made that will have vital consequences on the lives of women and their families. That is the problem the photo makes clear. Right now, the Afghanistan peace process is proceeding without the participation of women.

In 2000, the UN Security Council unanimously adopted Resolution 1325, obliging all UN member states to promote and protect women's meaningful participation in peace and security processes. Yet, UN Women's research has found that in 24 peace processes over the past two decades, women formed less than 8 percent of negotiating teams--and, as a result, women's needs and concerns are almost entirely missing from the resulting agreements. A study of 585 peace agreements concluded between 1990 and 2010 found that just 16 percent referred to women at all--only 3 percent had a reference to sexual- or gender-based violence.

When women are at the table, their concerns are more likely to be addressed. Their perspectives on human needs, peacebuilding, and reconciliation can be included. Their experiences can add to the understanding of the impact of war and everyday violence in communities, homes, and families--and therefore increase the likelihood of an authentic, lasting, and just peace.

Afghan women have been making this argument for years. Last week, 11 women human rights leaders were in Washington DC to meet with policy makers at the White House and in Congress. They pushed for the inclusion of more women leaders in peace talks to end the war in their country. They insisted that they are capable of contributing despite real--and at times tragic--risks to women who enter public life in Afghanistan.

The women repeated their message on PBS NewsHour a day before President Obama announced an accelerated withdrawal of troops from Afghanistan. None of the women rejected negotiations with the Taliban out of hand--indeed, they suggest that such direct dialogue could be beneficial. Yet, they pointed to a situation more complicated than simply talking to the Taliban when it comes to the security for Afghan women. Wazhma Frogh, from the Afghan Women's Network, said:

[the] Taliban are not the only threats to the women of Afghanistan or to all the people of Afghanistan. I have seen warlords who have raped women on the streets. We have seen people who have taken our lands. We have seen people who have done more damage.

Frogh also explained how people are driven to insurgency by the Afghan government itself:

It has no capacity in providing people with access to justice. So, a 13-year-old girl raped with 13 police, 13 men which--police officers among them, what do you expect people--like, the father of that girl says, I will blow myself up in a suicide attack, blowing up a government entity.

Negotiation tables most often include armed actors, who may be able to end the war but are little-equipped to bring the peace. As long as peace talks privilege those with arms--and those who derive their power from armed conflict--women and other nonviolent members of civil society will be excluded. The resulting "peace" deal too often redistributes power among a small group of armed actors, rather than creating a sustainable process that can establish a society based on justice, accountability, and inclusivity. History has shown that the end result is a recurring cycle of violence. Rangina Hamidi, a peace activist from Kandahar, spoke on PBS NewsHour about the tenuous gains Afghan women have made in the past ten years. She appeals:

Please, do not let Afghanistan fall back to the years of civil war, to the years of injustice and inhuman acts against all sectors of society, most especially women. So, for once, let's listen to the women and take their suggestions seriously.

As the US and Europe scramble for an exit strategy out of Afghanistan, they will need a way to claim relative success after 10 years of war. Isn't it time to look to Afghan women as agents of change and brokers of authentic human security? Peace requires this, and Afghanistan deserves this.