SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

Millions of people are still shocked and outraged by the state of Georgia's execution of Troy Davis for a murder he may not have committed.

People who had never heard of Davis or had never thought much about the death penalty suddenly confronted Georgia's senseless act of brutality. They asked themselves: How could the state kill someone in the face of so much doubt about his guilt?

The Sept. 21 execution struck a nerve unlike any other I have witnessed in years of work to abolish the death penalty. It triggered outrage across a broad spectrum that included celebrity tweeter Kim Kardashian, South African Archbishop Desmond Tutu, conservative columnist Kathleen Parker, and even Davis' former warden.

The many who are determined to heed Davis' final words -- "to continue to fight this fight" to end capital punishment -- can turn to another equally unjust case in St. Louis, Missouri.

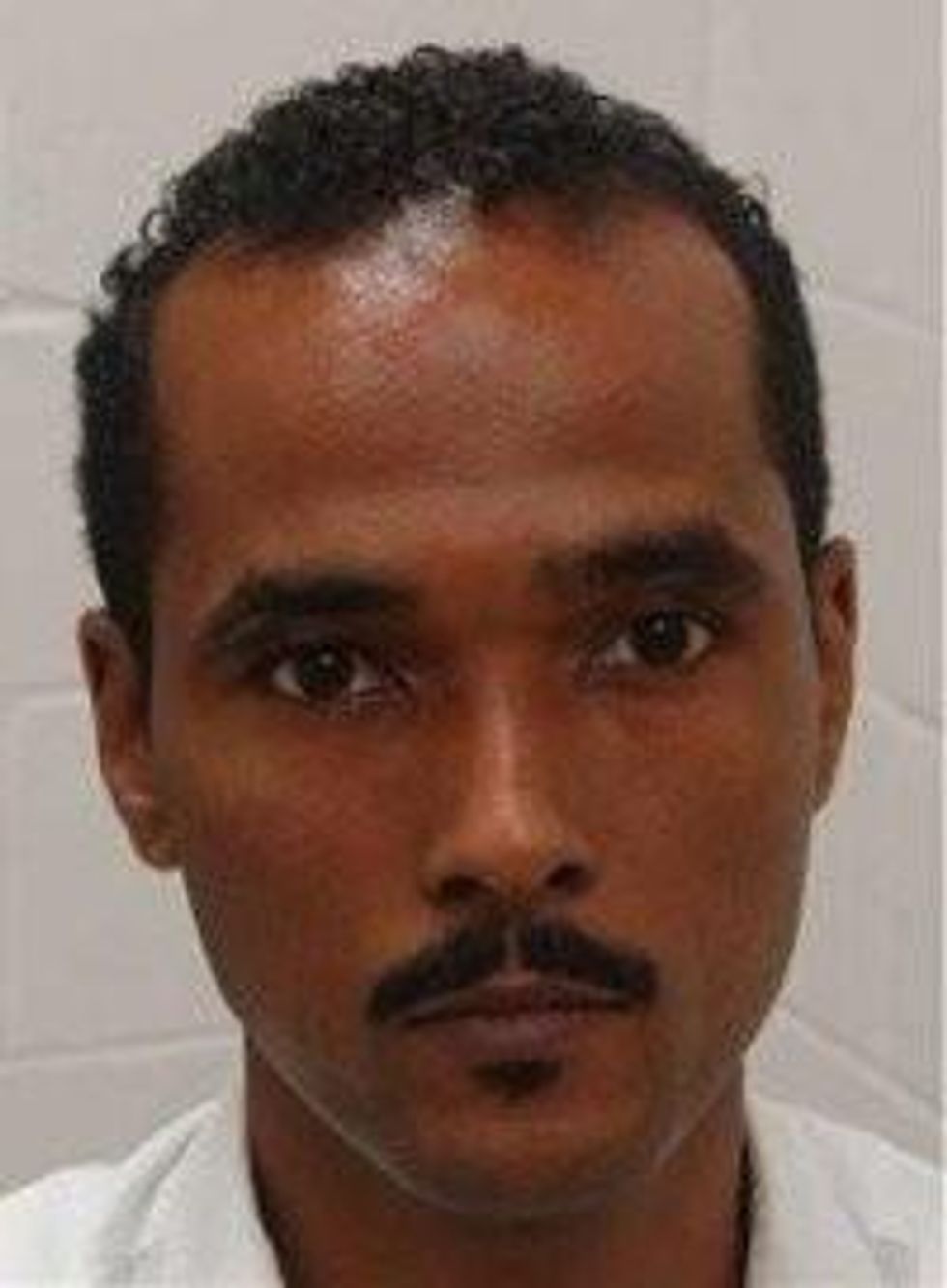

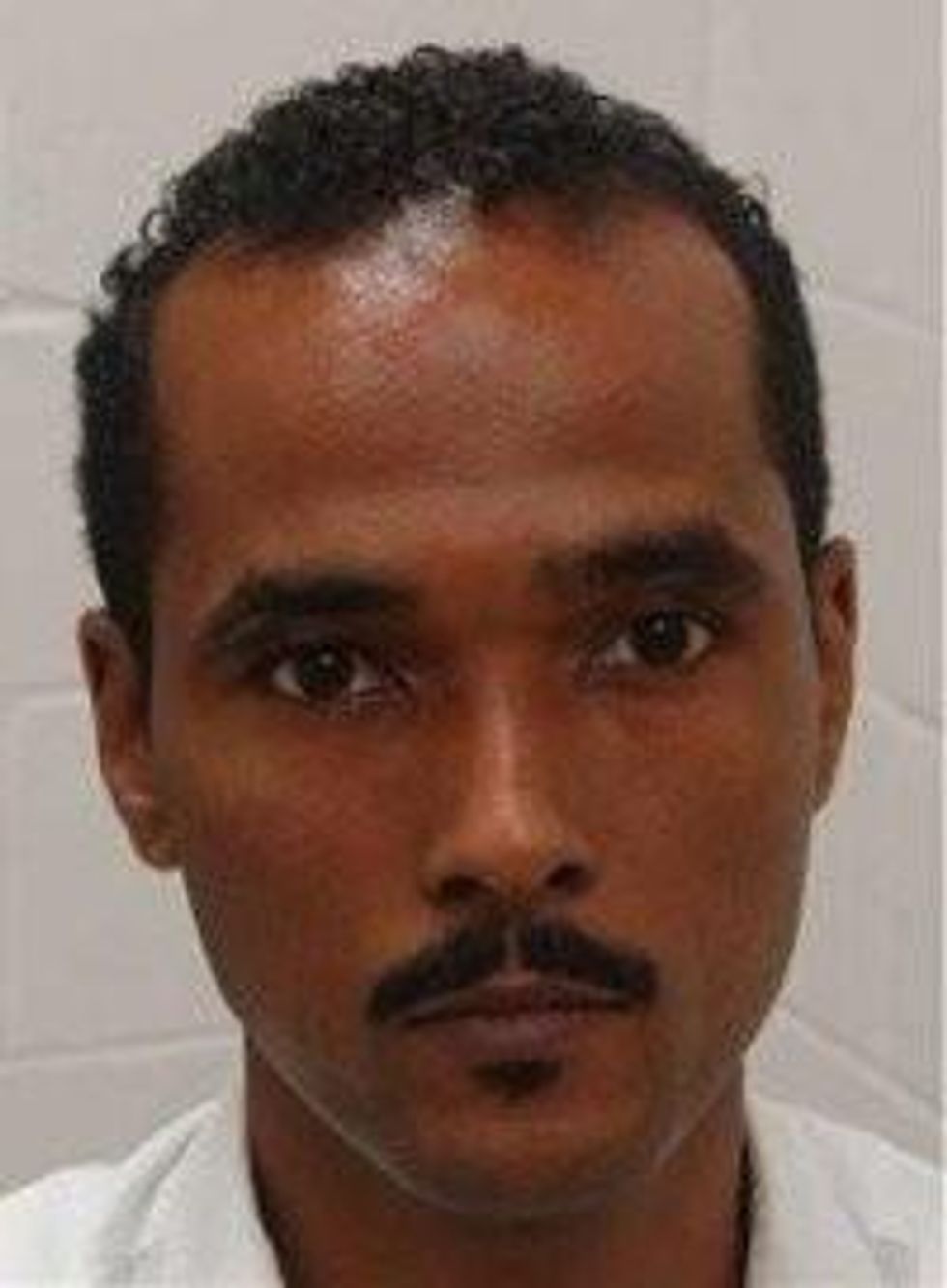

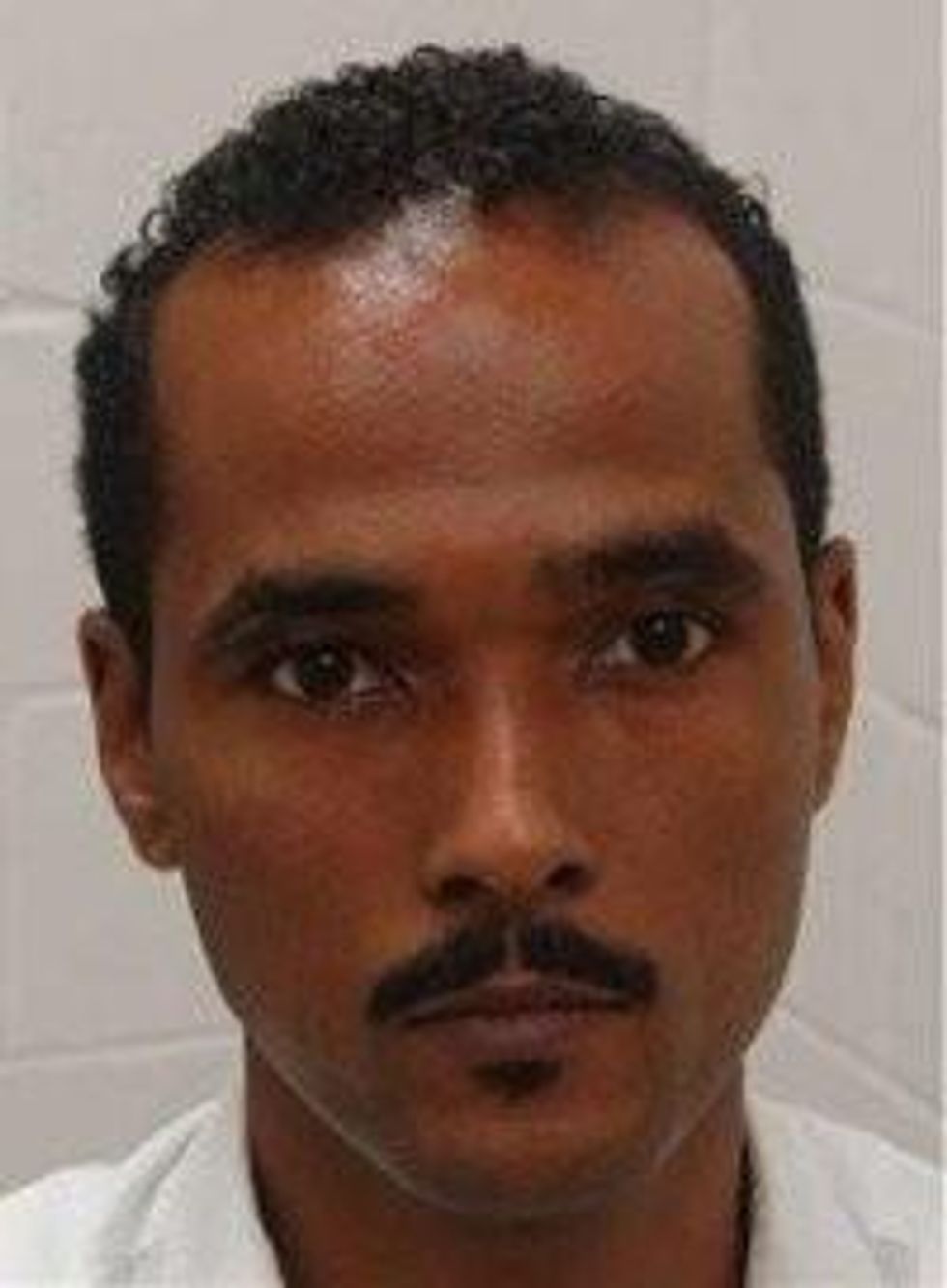

Reggie Clemons, 40, has spent half of his life behind bars. He's seeking clemency for a crime he may not have committed, just as Troy Davis did until his last breath.

Sentenced as an accomplice in the 1991 murder of two young white women, Clemons has already faced one execution date, and one of his co-defendants has already been executed. But a multitude of flaws both in the investigation and in the original trial leaves a massive amount of doubt about Clemons' guilt.

In April 1991, Julie and Robin Kerry plunged to their deaths from a bridge over the Mississippi River. Their white cousin Thomas Cummins initially took responsibility for their deaths, but later retracted his statement.

Instead Clemons and two other young men -- Marlin Gray and Antonio Richardson -- were convicted and received death sentences. Another man, Daniel Winfrey, received a lesser prison sentence in exchange for testifying against them. Gray, who like Clemons and Richardson was African-American, was executed in 2005. Richardson, who was 16 at the time of the crime, had his death sentence commuted to life in 2003. Winfrey, who is white, is now out of prison.

As in the Davis case, there's no physical evidence linking Clemons to the crime, only the testimony of two witnesses. The prosecution conceded that Clemons, who was 19 when the crime occurred, neither killed the victims nor planned the crime.

The allegations of police misconduct in the Clemons case are stark and disturbing. After his interrogation, Clemons' face was so swollen that the court where he was to be arraigned sent him instead to the emergency room.

The trial prosecutor was cited for "abusive and boorish" behavior. The defense lawyers -- a divorced husband and wife, one of whom lived in California and practiced tax law -- weren't up to the challenge.

The racial dynamic in the Clemons case can't be disputed. The trial was heard by a jury in which 10 of the 12 jurors were white. Higher courts have dismissed Clemons' appeals on these issues, on procedural technicalities rather than their merits.

In 2009, the Missouri Supreme Court stayed his execution and appointed a Special Master to take a second look at the case. Some new evidence has also emerged. Last year, a rape kit was discovered in the St. Louis police department's evidence room -- evidently forgotten for 19 years. That it sat unnoticed for so long casts further doubt on the quality of the investigation and trial.

After his alleged beating by police interrogators, Clemons had confessed to rape. He later retracted the confession and those charges were dropped after his murder conviction.

Worldwide pressure couldn't stop Georgia's machinery of death for Troy Davis. But the groundswell of protest his case generated proves that people are sickened by a criminal justice system that disregards the possibility of mistakes, errors, and doubts.

The Davis execution exposed a system with the power to kill but not to correct mistakes. Clemons' case will provide a similar test.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

Millions of people are still shocked and outraged by the state of Georgia's execution of Troy Davis for a murder he may not have committed.

People who had never heard of Davis or had never thought much about the death penalty suddenly confronted Georgia's senseless act of brutality. They asked themselves: How could the state kill someone in the face of so much doubt about his guilt?

The Sept. 21 execution struck a nerve unlike any other I have witnessed in years of work to abolish the death penalty. It triggered outrage across a broad spectrum that included celebrity tweeter Kim Kardashian, South African Archbishop Desmond Tutu, conservative columnist Kathleen Parker, and even Davis' former warden.

The many who are determined to heed Davis' final words -- "to continue to fight this fight" to end capital punishment -- can turn to another equally unjust case in St. Louis, Missouri.

Reggie Clemons, 40, has spent half of his life behind bars. He's seeking clemency for a crime he may not have committed, just as Troy Davis did until his last breath.

Sentenced as an accomplice in the 1991 murder of two young white women, Clemons has already faced one execution date, and one of his co-defendants has already been executed. But a multitude of flaws both in the investigation and in the original trial leaves a massive amount of doubt about Clemons' guilt.

In April 1991, Julie and Robin Kerry plunged to their deaths from a bridge over the Mississippi River. Their white cousin Thomas Cummins initially took responsibility for their deaths, but later retracted his statement.

Instead Clemons and two other young men -- Marlin Gray and Antonio Richardson -- were convicted and received death sentences. Another man, Daniel Winfrey, received a lesser prison sentence in exchange for testifying against them. Gray, who like Clemons and Richardson was African-American, was executed in 2005. Richardson, who was 16 at the time of the crime, had his death sentence commuted to life in 2003. Winfrey, who is white, is now out of prison.

As in the Davis case, there's no physical evidence linking Clemons to the crime, only the testimony of two witnesses. The prosecution conceded that Clemons, who was 19 when the crime occurred, neither killed the victims nor planned the crime.

The allegations of police misconduct in the Clemons case are stark and disturbing. After his interrogation, Clemons' face was so swollen that the court where he was to be arraigned sent him instead to the emergency room.

The trial prosecutor was cited for "abusive and boorish" behavior. The defense lawyers -- a divorced husband and wife, one of whom lived in California and practiced tax law -- weren't up to the challenge.

The racial dynamic in the Clemons case can't be disputed. The trial was heard by a jury in which 10 of the 12 jurors were white. Higher courts have dismissed Clemons' appeals on these issues, on procedural technicalities rather than their merits.

In 2009, the Missouri Supreme Court stayed his execution and appointed a Special Master to take a second look at the case. Some new evidence has also emerged. Last year, a rape kit was discovered in the St. Louis police department's evidence room -- evidently forgotten for 19 years. That it sat unnoticed for so long casts further doubt on the quality of the investigation and trial.

After his alleged beating by police interrogators, Clemons had confessed to rape. He later retracted the confession and those charges were dropped after his murder conviction.

Worldwide pressure couldn't stop Georgia's machinery of death for Troy Davis. But the groundswell of protest his case generated proves that people are sickened by a criminal justice system that disregards the possibility of mistakes, errors, and doubts.

The Davis execution exposed a system with the power to kill but not to correct mistakes. Clemons' case will provide a similar test.

Millions of people are still shocked and outraged by the state of Georgia's execution of Troy Davis for a murder he may not have committed.

People who had never heard of Davis or had never thought much about the death penalty suddenly confronted Georgia's senseless act of brutality. They asked themselves: How could the state kill someone in the face of so much doubt about his guilt?

The Sept. 21 execution struck a nerve unlike any other I have witnessed in years of work to abolish the death penalty. It triggered outrage across a broad spectrum that included celebrity tweeter Kim Kardashian, South African Archbishop Desmond Tutu, conservative columnist Kathleen Parker, and even Davis' former warden.

The many who are determined to heed Davis' final words -- "to continue to fight this fight" to end capital punishment -- can turn to another equally unjust case in St. Louis, Missouri.

Reggie Clemons, 40, has spent half of his life behind bars. He's seeking clemency for a crime he may not have committed, just as Troy Davis did until his last breath.

Sentenced as an accomplice in the 1991 murder of two young white women, Clemons has already faced one execution date, and one of his co-defendants has already been executed. But a multitude of flaws both in the investigation and in the original trial leaves a massive amount of doubt about Clemons' guilt.

In April 1991, Julie and Robin Kerry plunged to their deaths from a bridge over the Mississippi River. Their white cousin Thomas Cummins initially took responsibility for their deaths, but later retracted his statement.

Instead Clemons and two other young men -- Marlin Gray and Antonio Richardson -- were convicted and received death sentences. Another man, Daniel Winfrey, received a lesser prison sentence in exchange for testifying against them. Gray, who like Clemons and Richardson was African-American, was executed in 2005. Richardson, who was 16 at the time of the crime, had his death sentence commuted to life in 2003. Winfrey, who is white, is now out of prison.

As in the Davis case, there's no physical evidence linking Clemons to the crime, only the testimony of two witnesses. The prosecution conceded that Clemons, who was 19 when the crime occurred, neither killed the victims nor planned the crime.

The allegations of police misconduct in the Clemons case are stark and disturbing. After his interrogation, Clemons' face was so swollen that the court where he was to be arraigned sent him instead to the emergency room.

The trial prosecutor was cited for "abusive and boorish" behavior. The defense lawyers -- a divorced husband and wife, one of whom lived in California and practiced tax law -- weren't up to the challenge.

The racial dynamic in the Clemons case can't be disputed. The trial was heard by a jury in which 10 of the 12 jurors were white. Higher courts have dismissed Clemons' appeals on these issues, on procedural technicalities rather than their merits.

In 2009, the Missouri Supreme Court stayed his execution and appointed a Special Master to take a second look at the case. Some new evidence has also emerged. Last year, a rape kit was discovered in the St. Louis police department's evidence room -- evidently forgotten for 19 years. That it sat unnoticed for so long casts further doubt on the quality of the investigation and trial.

After his alleged beating by police interrogators, Clemons had confessed to rape. He later retracted the confession and those charges were dropped after his murder conviction.

Worldwide pressure couldn't stop Georgia's machinery of death for Troy Davis. But the groundswell of protest his case generated proves that people are sickened by a criminal justice system that disregards the possibility of mistakes, errors, and doubts.

The Davis execution exposed a system with the power to kill but not to correct mistakes. Clemons' case will provide a similar test.