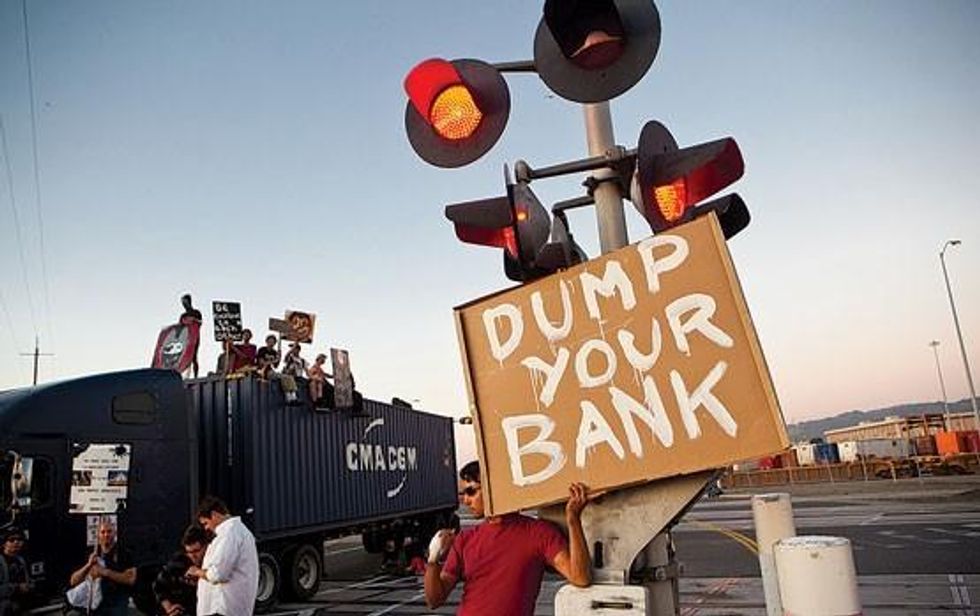

Since the big corporate banks crashed the economy in 2008, they've been rewarded with bailouts, tax breaks, and bonuses, while American workers lose jobs and homes. Little wonder that many Americans--and now, institutions and local governments--have been closing their accounts at big corporate banks and transferring their money to community banks and credit unions. The idea is to send a strong message about responsibility to government and Wall Street, while supporting institutions that genuinely stimulate local economies.

Bank Transfer Day was publicized over five weeks, largely through social networks. In that period, credit unions received an estimated $4.5 billion in new deposits transferred from banks, according to the Credit Union National Association.

Encouraged by the popularity of the "Move Your Money" campaign, citizens are calling for institutions to be accountable and "Move Our Money." A number of schools, churches, and local governments across the country are transferring large sums, or at least considering it, in what looks like the beginning of a broad movement to invest in local economies instead of Wall Street.

Last year the city of San Jose moved nearly $1 billion from Bank of America because of the bank's high record of home foreclosures. City Council members linked foreclosures to lost tax revenues and cuts to jobs and services, and urged other U.S. cities to follow San Jose's example. More recently, in November 2011, the Seattle City Council responded to the Occupy movement by unanimously passing a resolution to review its banking and investment practices "to ensure that public funds are invested in responsible financial institutions that support our community." Officials in Portland, Ore., Los Angeles, and New York City are discussing proposals that address how and where city funds are invested. Massachusetts launched the Small Business Banking Partnership initiative last year to leverage small business loans and has already deposited $106 million in state reserve funds into community banks.

Student activists and the Responsible Endowments Coalition are urging colleges and universities--some of which have assets comparable to those of a town or city--to move at least a portion of their endowments from Wall Street. The Peralta Community Colleges District in California, with an annual budget of $140 million, has done just that. The district's board of trustees voted unanimously in November to move its assets into community banks and credit unions.

Churches and faith organizations are moving their money too. Congregations in the California interfaith coalition LA Voice vowed to divest $2 million from Wells Fargo and Bank of America, ending a 200-year relationship with the big banks. The Most Holy Trinity Catholic Church in East San Jose, Calif., pulled $3 million out of Bank of America and reinvested the funds into Micro Branch, a division of Self-Help Federal Credit Union designed to assist underserved communities.

Moving money is most effective where banking practices and investments are transparent. Oregon Banks Local represents small business, family farms, and community banks. It offers a website tool that ranks local banks and credit unions on criteria like headquarters location, jobs created, and extent of local investment to show which financial institutions truly serve local communities.

"People from all walks of life are angry at the banks," says Ilana Berger, co-director of The New Bottom Line, a national campaign that promotes moving money from Wall Street. But the broad appeal of this grassroots movement toward financial reform is based on more than anger or strategy. "It's a way to move our money to follow our values," says Berger. "It's an opportunity to really protest against the banks, but also a way to show what we want them to be."