SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

Compared to its current clamor, the Quebec student protests began last year with a whimper. In March of 2011, Finance Minister Raymond Bachand announced that Quebec student tuition would increase by $325 every year for five years. By August, student organizations were debating the possibility of an unlimited student strike. In February 2012, student organizations from several colleges and universities endorsed the action and blockaded Montreal's Jacques Cartier Bridge, a major artery in the city.

Compared to its current clamor, the Quebec student protests began last year with a whimper. In March of 2011, Finance Minister Raymond Bachand announced that Quebec student tuition would increase by $325 every year for five years. By August, student organizations were debating the possibility of an unlimited student strike. In February 2012, student organizations from several colleges and universities endorsed the action and blockaded Montreal's Jacques Cartier Bridge, a major artery in the city. Over the next few months, numerous violent clashes with Montreal police led to mass arrests. But on May 18, 2012, Quebec's Premier Charest raised the stakes by instituting "special" Bill 78. This law prohibited protests within 50 meters of any university, effectively making all of downtown Montreal a protest-free zone. May 22 marked the 100th day of the strike, and nearly 400,000 people marched through downtown joyously defying the law.

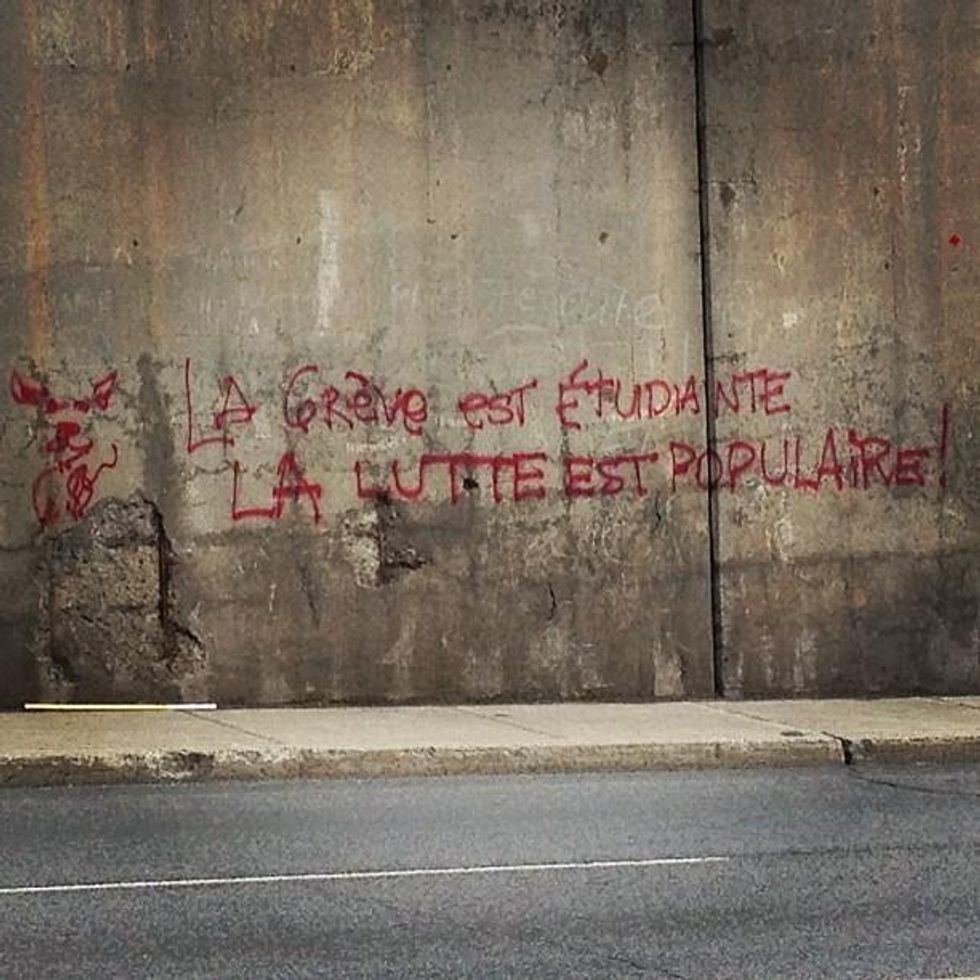

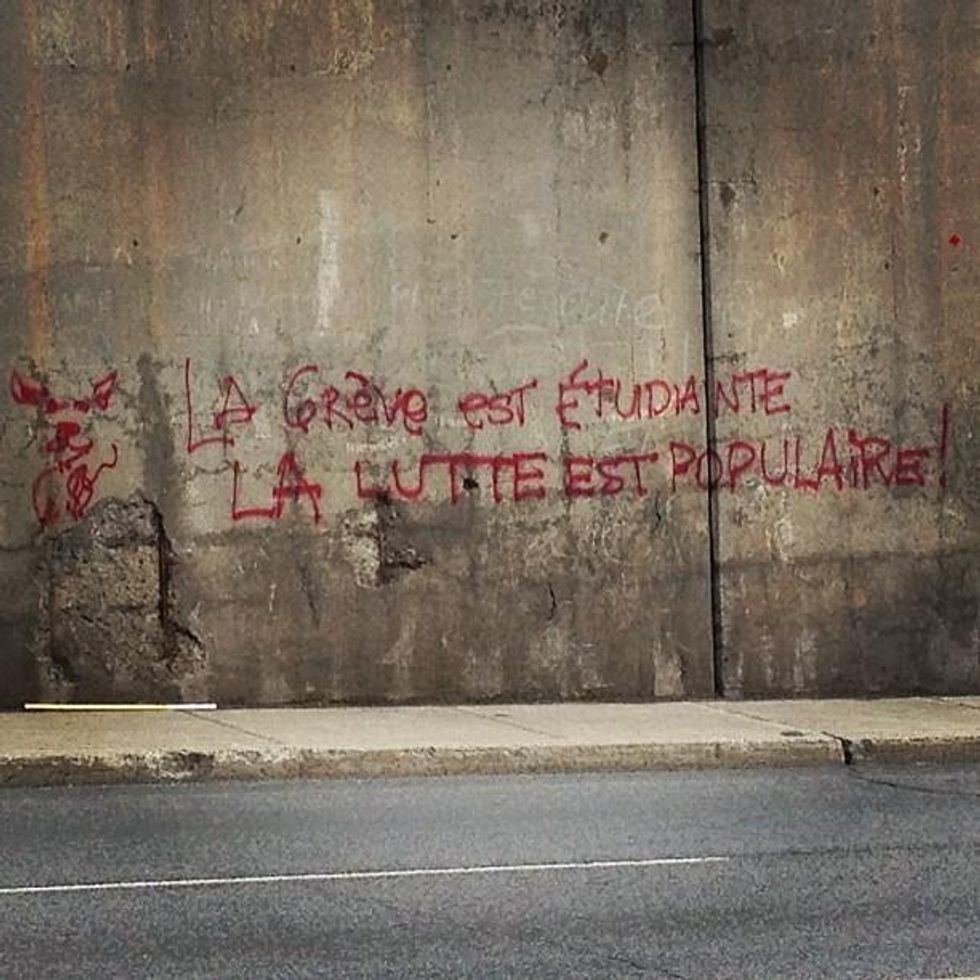

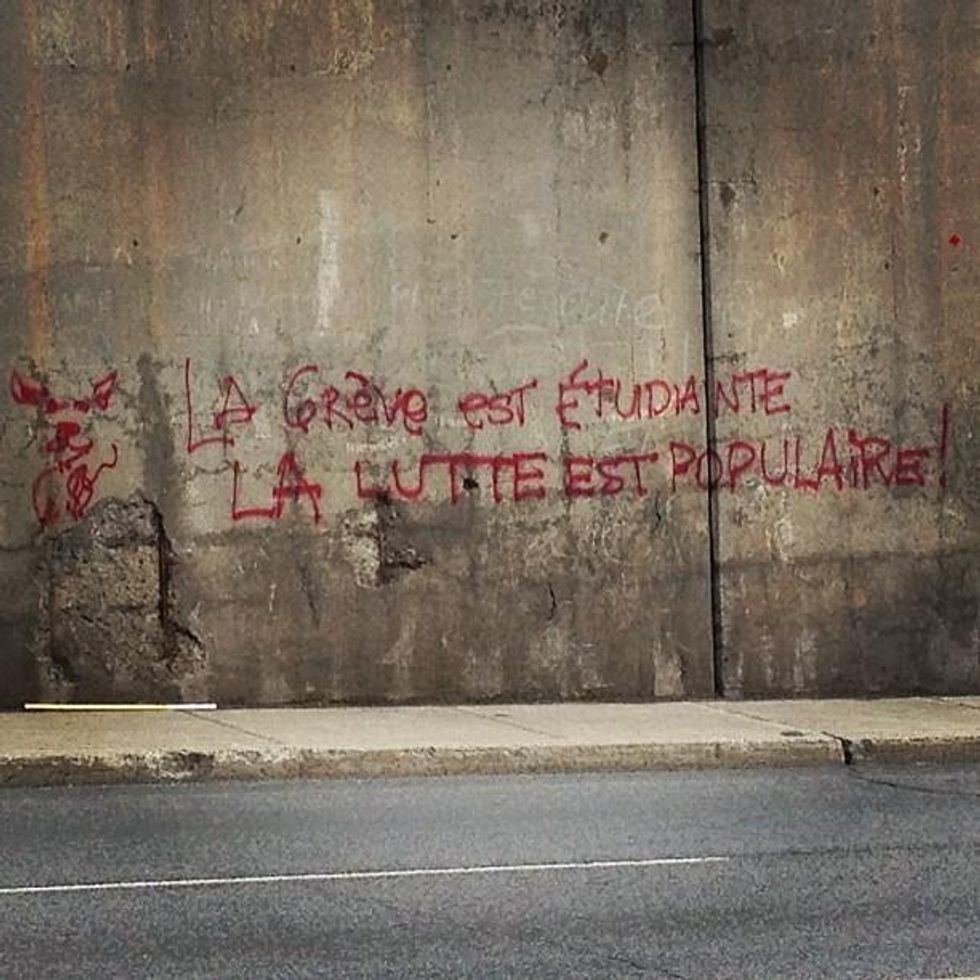

As the state repression of the student movement heightened, so has the creativity of the students' tactical repertoire, which has expanded to include marching nude, community assemblies and, especially important in Quebec's bilingual society, the tactical use of translation though music and words.

J.B. Staniforth, a McGill graduate and writer, explains that there is a Francophone cultural memory that differs from its Anglophone counterpart. "People who don't speak French have no idea how different Francophone culture and values are from Anglophone culture," he says, "particularly given the history of Franco culture rooted in protest and rebellion. The Quebecois owe much of their present identity to rebelling against the authoritarian rule of Duplessis in the fifties." Maurice Duplessis, Quebec's Premier from 1936 to 1939 and 1944 to 1959 is best remembered for corrupt politics and violently suppressing the left.

Resisters in Quebec have recently taken up two translation-based tactics in particular that aim to increase participation in the protests and bridge the cultural divide. Protesters have rallied around a series of musical night marches to counteract the increased police pressure. They've also started a blog to pit the English media's coverage against that of the French.

After Bill 78 passed, a decentralized form of resistance fomented in neighborhoods across the city, in which at 8 o'clock every night people participate in the "casserole protests" by banging on pots and pans while marching near their homes. The Montreal police Twitter account, which usually provides information about the location of the central protest, suggests that the police have been unable to follow, corral or control these distributed actions. People of all ages take to the streets with a spirit of joy and resistance. This tactic, borrowed from movements in places like Argentina and Chile, has been taken up by solidarity marches around the world, including a recent one by Occupy Wall Street in New York.

In Montreal, every act of police or legislative oppression is met with new neighborhood nodes emerging, from the suburbs of Saint Hubert to the island communities of Verdun and LaSalle. The clinks and clanks of pots on balconies turn into roaming clusters of people converging at the borders of neighboring boroughs. They stop briefly along the way to greet one another. This is truly a unique moment for the city, as many political issues hinge on a deep cultural divide between Francophones and Anglophones not just in the Province, but also across Canada. The music of the casseroles translates their struggles, giving no preference to a single voice or language. Speaking through music provides the levity and spontaneity necessary to fight back against state oppression during dark times. But this is not the only space in which an act of translation is uniting the people of Montreal and of Canada as a whole.

The focus of these protests in other locales is different, but they are united by a common cause of valuing affordable education for the social good it provides. That is something that anyone, in any language, should be able to understand.

The movement has faced a challenge in that mainstream media accounts of it reflect a severe cultural divide. While the English media portray the students as entitled and naive, usually siding with the government, the French reports depict a vastly different scene of students fighting for the civil rights of generations to come. Disheartened by the English language media coverage of Bill 78, a group of friends hatched a plan to fight back using a tumblr blog, aptly titled Translating the Printemps Erable (Maple Spring). They chose tumblr as a platform because it allows for the quick dissemination of information, along with the ability for others to submit content.

Greame Williams, an admin for the site, elaborates on its origins:

I subscribe to the Saturday edition of Le Devoir (a French-language paper), and the morning after Law 78 was passed, the editorial line of the paper was unambiguous in condemning it as a likely illegal and unconstitutional authoritarian act. Then I looked at the Globe and Mail, and they thought that the law was justified in ending the student strike. That was the breaking point leading to the blog being actually created, but poor coverage in the English-language media generally led up to this.

By setting the mainstream outlets against one another, the blog undermines their claims to journalistic objectivity.

A. Wilson, a translator for the site, adds that the problem is also rooted in the limitations of monolingual publishers themselves. "The French media," she explains, "gets more in-depth, primary-source interviews with main players in the crisis just because many are more comfortable interviewing in French, typically their mother tongue."

The great irony of the English media's portrayal of the protests is that many involved in the blog and in the casserole marches do not directly benefit from the students' cause and see it as anything but naive. A woman who goes by Anna, an admin for the Maple Spring blog, says:

I am not a student, but I hope to have kids someday and so I am invested in education being affordable in that way. But more importantly, I will benefit from a more accessible, equitable Quebec if the students "win" because we all do; I want my neighbors to be able to educate themselves, and I want our society to have a high and rigorous level of debate. All of this is only possible with accessible education.

With people like Anna recognizing themselves in the students' struggle, the task of translation and breaking down boundaries seems all the more important. It may help many more of them to turn from bystanders to participants.

"Casseroles Night in Canada" is quickly replacing the famed "Hockey Night in Canada," with solidarity protests across the globe last week, organized largely through online social media. The focus of these protests in other locales is different, but they are united by a common cause of valuing affordable education for the social good it provides. That is something that anyone, in any language, should be able to understand.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

Compared to its current clamor, the Quebec student protests began last year with a whimper. In March of 2011, Finance Minister Raymond Bachand announced that Quebec student tuition would increase by $325 every year for five years. By August, student organizations were debating the possibility of an unlimited student strike. In February 2012, student organizations from several colleges and universities endorsed the action and blockaded Montreal's Jacques Cartier Bridge, a major artery in the city. Over the next few months, numerous violent clashes with Montreal police led to mass arrests. But on May 18, 2012, Quebec's Premier Charest raised the stakes by instituting "special" Bill 78. This law prohibited protests within 50 meters of any university, effectively making all of downtown Montreal a protest-free zone. May 22 marked the 100th day of the strike, and nearly 400,000 people marched through downtown joyously defying the law.

As the state repression of the student movement heightened, so has the creativity of the students' tactical repertoire, which has expanded to include marching nude, community assemblies and, especially important in Quebec's bilingual society, the tactical use of translation though music and words.

J.B. Staniforth, a McGill graduate and writer, explains that there is a Francophone cultural memory that differs from its Anglophone counterpart. "People who don't speak French have no idea how different Francophone culture and values are from Anglophone culture," he says, "particularly given the history of Franco culture rooted in protest and rebellion. The Quebecois owe much of their present identity to rebelling against the authoritarian rule of Duplessis in the fifties." Maurice Duplessis, Quebec's Premier from 1936 to 1939 and 1944 to 1959 is best remembered for corrupt politics and violently suppressing the left.

Resisters in Quebec have recently taken up two translation-based tactics in particular that aim to increase participation in the protests and bridge the cultural divide. Protesters have rallied around a series of musical night marches to counteract the increased police pressure. They've also started a blog to pit the English media's coverage against that of the French.

After Bill 78 passed, a decentralized form of resistance fomented in neighborhoods across the city, in which at 8 o'clock every night people participate in the "casserole protests" by banging on pots and pans while marching near their homes. The Montreal police Twitter account, which usually provides information about the location of the central protest, suggests that the police have been unable to follow, corral or control these distributed actions. People of all ages take to the streets with a spirit of joy and resistance. This tactic, borrowed from movements in places like Argentina and Chile, has been taken up by solidarity marches around the world, including a recent one by Occupy Wall Street in New York.

In Montreal, every act of police or legislative oppression is met with new neighborhood nodes emerging, from the suburbs of Saint Hubert to the island communities of Verdun and LaSalle. The clinks and clanks of pots on balconies turn into roaming clusters of people converging at the borders of neighboring boroughs. They stop briefly along the way to greet one another. This is truly a unique moment for the city, as many political issues hinge on a deep cultural divide between Francophones and Anglophones not just in the Province, but also across Canada. The music of the casseroles translates their struggles, giving no preference to a single voice or language. Speaking through music provides the levity and spontaneity necessary to fight back against state oppression during dark times. But this is not the only space in which an act of translation is uniting the people of Montreal and of Canada as a whole.

The focus of these protests in other locales is different, but they are united by a common cause of valuing affordable education for the social good it provides. That is something that anyone, in any language, should be able to understand.

The movement has faced a challenge in that mainstream media accounts of it reflect a severe cultural divide. While the English media portray the students as entitled and naive, usually siding with the government, the French reports depict a vastly different scene of students fighting for the civil rights of generations to come. Disheartened by the English language media coverage of Bill 78, a group of friends hatched a plan to fight back using a tumblr blog, aptly titled Translating the Printemps Erable (Maple Spring). They chose tumblr as a platform because it allows for the quick dissemination of information, along with the ability for others to submit content.

Greame Williams, an admin for the site, elaborates on its origins:

I subscribe to the Saturday edition of Le Devoir (a French-language paper), and the morning after Law 78 was passed, the editorial line of the paper was unambiguous in condemning it as a likely illegal and unconstitutional authoritarian act. Then I looked at the Globe and Mail, and they thought that the law was justified in ending the student strike. That was the breaking point leading to the blog being actually created, but poor coverage in the English-language media generally led up to this.

By setting the mainstream outlets against one another, the blog undermines their claims to journalistic objectivity.

A. Wilson, a translator for the site, adds that the problem is also rooted in the limitations of monolingual publishers themselves. "The French media," she explains, "gets more in-depth, primary-source interviews with main players in the crisis just because many are more comfortable interviewing in French, typically their mother tongue."

The great irony of the English media's portrayal of the protests is that many involved in the blog and in the casserole marches do not directly benefit from the students' cause and see it as anything but naive. A woman who goes by Anna, an admin for the Maple Spring blog, says:

I am not a student, but I hope to have kids someday and so I am invested in education being affordable in that way. But more importantly, I will benefit from a more accessible, equitable Quebec if the students "win" because we all do; I want my neighbors to be able to educate themselves, and I want our society to have a high and rigorous level of debate. All of this is only possible with accessible education.

With people like Anna recognizing themselves in the students' struggle, the task of translation and breaking down boundaries seems all the more important. It may help many more of them to turn from bystanders to participants.

"Casseroles Night in Canada" is quickly replacing the famed "Hockey Night in Canada," with solidarity protests across the globe last week, organized largely through online social media. The focus of these protests in other locales is different, but they are united by a common cause of valuing affordable education for the social good it provides. That is something that anyone, in any language, should be able to understand.

Compared to its current clamor, the Quebec student protests began last year with a whimper. In March of 2011, Finance Minister Raymond Bachand announced that Quebec student tuition would increase by $325 every year for five years. By August, student organizations were debating the possibility of an unlimited student strike. In February 2012, student organizations from several colleges and universities endorsed the action and blockaded Montreal's Jacques Cartier Bridge, a major artery in the city. Over the next few months, numerous violent clashes with Montreal police led to mass arrests. But on May 18, 2012, Quebec's Premier Charest raised the stakes by instituting "special" Bill 78. This law prohibited protests within 50 meters of any university, effectively making all of downtown Montreal a protest-free zone. May 22 marked the 100th day of the strike, and nearly 400,000 people marched through downtown joyously defying the law.

As the state repression of the student movement heightened, so has the creativity of the students' tactical repertoire, which has expanded to include marching nude, community assemblies and, especially important in Quebec's bilingual society, the tactical use of translation though music and words.

J.B. Staniforth, a McGill graduate and writer, explains that there is a Francophone cultural memory that differs from its Anglophone counterpart. "People who don't speak French have no idea how different Francophone culture and values are from Anglophone culture," he says, "particularly given the history of Franco culture rooted in protest and rebellion. The Quebecois owe much of their present identity to rebelling against the authoritarian rule of Duplessis in the fifties." Maurice Duplessis, Quebec's Premier from 1936 to 1939 and 1944 to 1959 is best remembered for corrupt politics and violently suppressing the left.

Resisters in Quebec have recently taken up two translation-based tactics in particular that aim to increase participation in the protests and bridge the cultural divide. Protesters have rallied around a series of musical night marches to counteract the increased police pressure. They've also started a blog to pit the English media's coverage against that of the French.

After Bill 78 passed, a decentralized form of resistance fomented in neighborhoods across the city, in which at 8 o'clock every night people participate in the "casserole protests" by banging on pots and pans while marching near their homes. The Montreal police Twitter account, which usually provides information about the location of the central protest, suggests that the police have been unable to follow, corral or control these distributed actions. People of all ages take to the streets with a spirit of joy and resistance. This tactic, borrowed from movements in places like Argentina and Chile, has been taken up by solidarity marches around the world, including a recent one by Occupy Wall Street in New York.

In Montreal, every act of police or legislative oppression is met with new neighborhood nodes emerging, from the suburbs of Saint Hubert to the island communities of Verdun and LaSalle. The clinks and clanks of pots on balconies turn into roaming clusters of people converging at the borders of neighboring boroughs. They stop briefly along the way to greet one another. This is truly a unique moment for the city, as many political issues hinge on a deep cultural divide between Francophones and Anglophones not just in the Province, but also across Canada. The music of the casseroles translates their struggles, giving no preference to a single voice or language. Speaking through music provides the levity and spontaneity necessary to fight back against state oppression during dark times. But this is not the only space in which an act of translation is uniting the people of Montreal and of Canada as a whole.

The focus of these protests in other locales is different, but they are united by a common cause of valuing affordable education for the social good it provides. That is something that anyone, in any language, should be able to understand.

The movement has faced a challenge in that mainstream media accounts of it reflect a severe cultural divide. While the English media portray the students as entitled and naive, usually siding with the government, the French reports depict a vastly different scene of students fighting for the civil rights of generations to come. Disheartened by the English language media coverage of Bill 78, a group of friends hatched a plan to fight back using a tumblr blog, aptly titled Translating the Printemps Erable (Maple Spring). They chose tumblr as a platform because it allows for the quick dissemination of information, along with the ability for others to submit content.

Greame Williams, an admin for the site, elaborates on its origins:

I subscribe to the Saturday edition of Le Devoir (a French-language paper), and the morning after Law 78 was passed, the editorial line of the paper was unambiguous in condemning it as a likely illegal and unconstitutional authoritarian act. Then I looked at the Globe and Mail, and they thought that the law was justified in ending the student strike. That was the breaking point leading to the blog being actually created, but poor coverage in the English-language media generally led up to this.

By setting the mainstream outlets against one another, the blog undermines their claims to journalistic objectivity.

A. Wilson, a translator for the site, adds that the problem is also rooted in the limitations of monolingual publishers themselves. "The French media," she explains, "gets more in-depth, primary-source interviews with main players in the crisis just because many are more comfortable interviewing in French, typically their mother tongue."

The great irony of the English media's portrayal of the protests is that many involved in the blog and in the casserole marches do not directly benefit from the students' cause and see it as anything but naive. A woman who goes by Anna, an admin for the Maple Spring blog, says:

I am not a student, but I hope to have kids someday and so I am invested in education being affordable in that way. But more importantly, I will benefit from a more accessible, equitable Quebec if the students "win" because we all do; I want my neighbors to be able to educate themselves, and I want our society to have a high and rigorous level of debate. All of this is only possible with accessible education.

With people like Anna recognizing themselves in the students' struggle, the task of translation and breaking down boundaries seems all the more important. It may help many more of them to turn from bystanders to participants.

"Casseroles Night in Canada" is quickly replacing the famed "Hockey Night in Canada," with solidarity protests across the globe last week, organized largely through online social media. The focus of these protests in other locales is different, but they are united by a common cause of valuing affordable education for the social good it provides. That is something that anyone, in any language, should be able to understand.