SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

Listening to the talk in Washington is depressing these days for those concerned about the future of our planet.

Listening to the talk in Washington is depressing these days for those concerned about the future of our planet.

When she isn't busy fighting fracking or organizing communities, Deirdre Lally teaches free health and nutrition classes in rural northeastern Pennsylvania. On Lally's commute, she passes dozens of gas operation trucks and a number of active strip mines.

"While teaching children and seniors how to stay healthy, I look out the window of the classroom and I see nothing but strip mines surrounding the town," Lally shared in a meeting between activists fighting mountaintop removal and fracking this past spring. "Poison is running into the streams and water tables and coal dust is in the air. How is a population to be healthy when extractive industries are taking over their towns?"

Lally was at Mountain Justice Spring Break, an annual training camp for anti-mountaintop removal activists. For the past several years, students, community members and activists have gathered together each spring to share skills and fight mountaintop removal, an extremely destructive form of strip mining that scrapes off the top of mountains to get to the coal seams below. Since the 1990s, a growing coalition of activists have engaged in organized resistance to mountaintop removal, using tactics as diverse as media campaigns, direct actions and lobbying.

In a region that stretches from New York to Ohio, a geologic formation called the Marcellus Shale has become a new hot spot of environmental injustice. There, gas companies are using a process called hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, which can crack the water table and lead to groundwater contamination, among other effects. In rural Pennsylvania, where Lally lives and works, gas companies are paying off landowners to frack on their property.

This year, Mountain Justice Spring Break was located in northern West Virginia, where fracking is currently wreaking havoc upon the landscape. The intention of the location was to bring activists fighting mountaintop removal in Appalachia and fracking in the Marcellus Shale region together to share skills, strategies and experiences. The camp was an early step towards a larger vision: to turn the dozens of fights against resource extraction across the country into a unified movement for land, water and health.

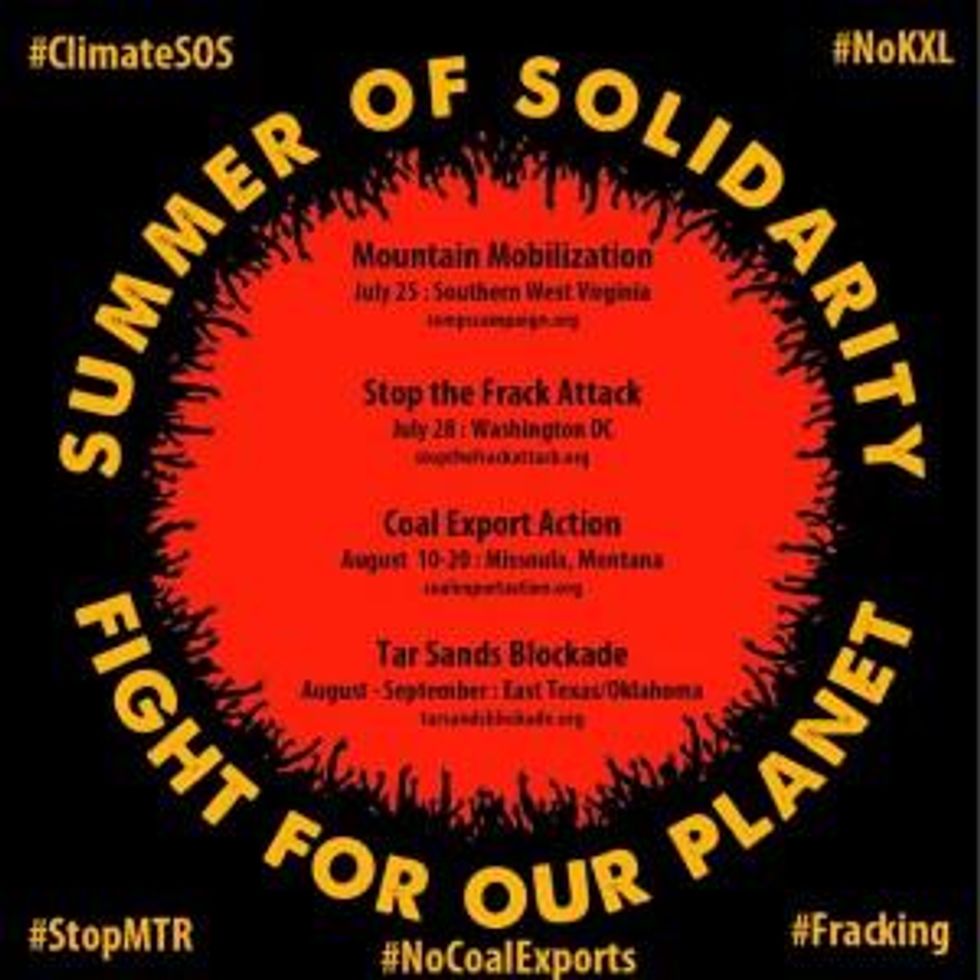

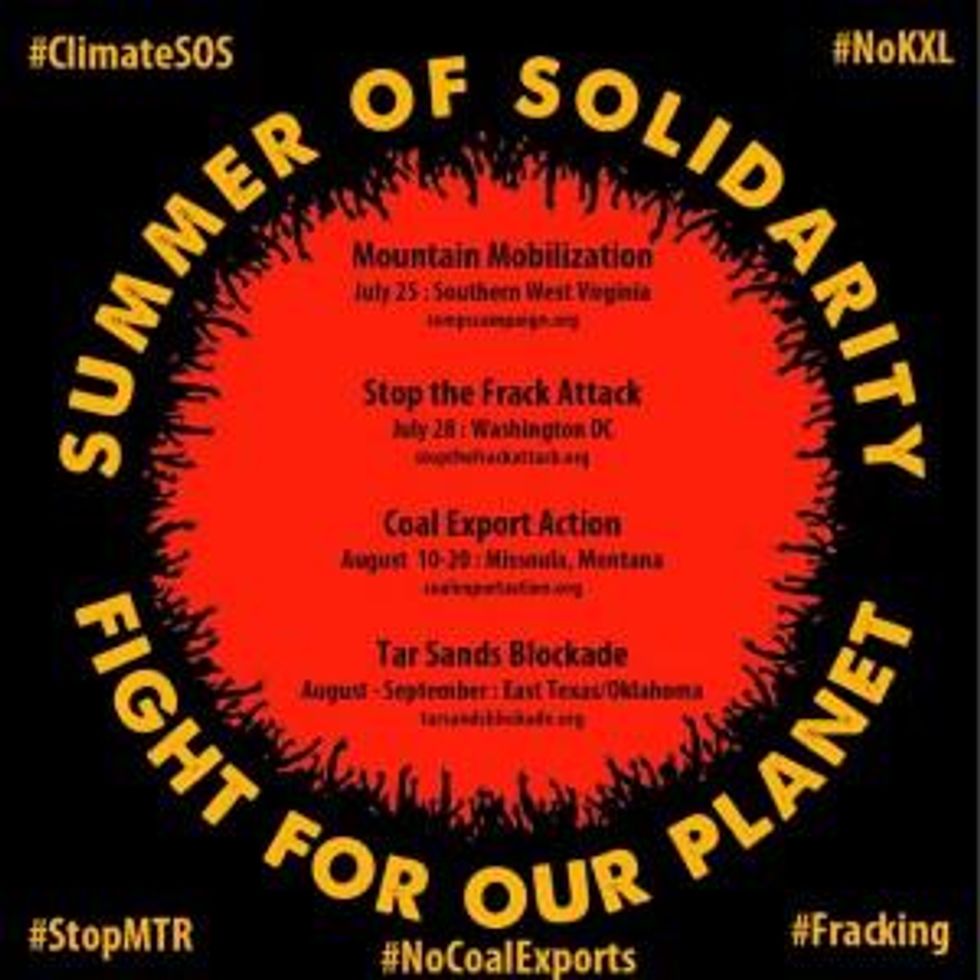

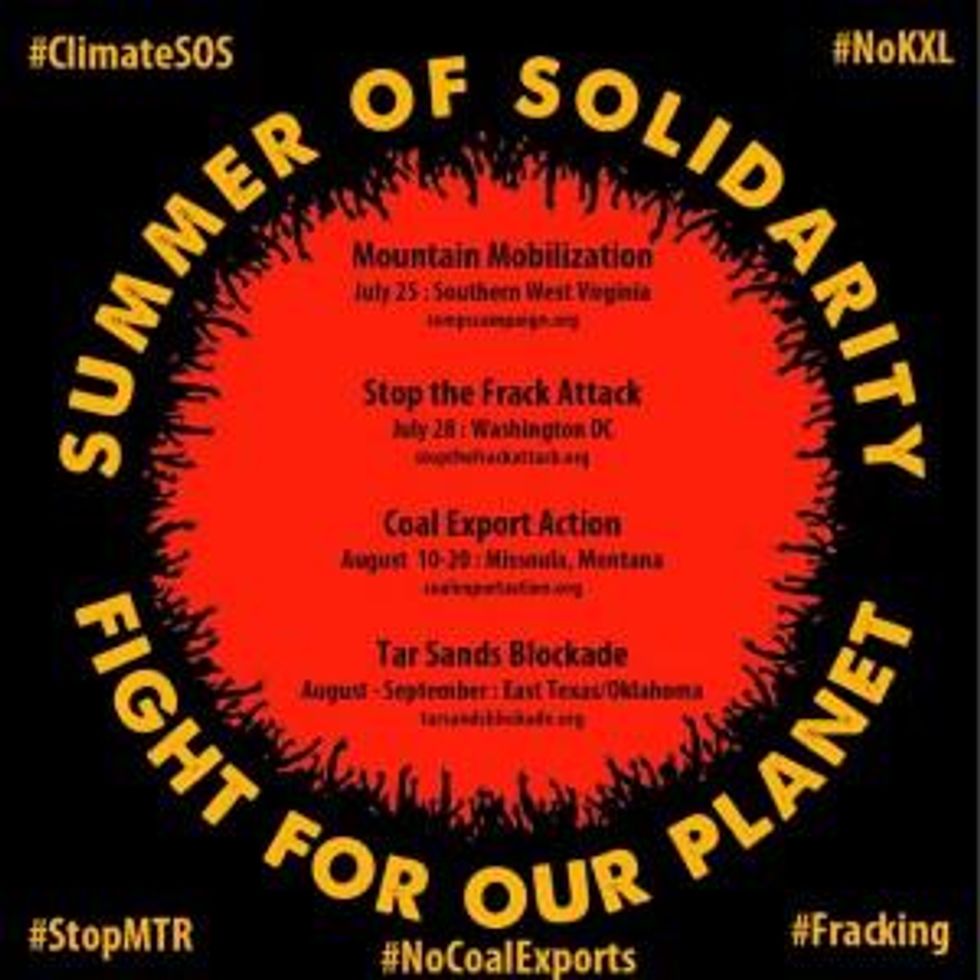

Beginning in late May, strategizing and discussion grew into a plethora of actions against coal, fracking and other extractive industries. These actions have included a lock down to a coal barge on a West Virginia river and two blockades of wastewater injection wells in Ohio. In central Pennsylvania, Earth First! activists at the Moshannon State Forest blockaded a road to a gas rig, leading to the first shut down of a fracking site in United States' history. Much more is planned this summer. In August, Coal Export Action will set up camp at the state Capitol in Helena, Montana to oppose the Otter Creek Mine and other proposed mining projects in Montana and Wyoming. The national anti-fracking movement is coming together to Stop The Frack Attack in D.C., while in north Texas, citizens are preparing to blockade the Keystone XL pipeline. Taken as a whole, the actions this summer have been nicknamed the National Uprising Against Extraction.

The mobilization is being organized by the RAMPS (Radical Action for Mountain People's Survival) Campaign. Since its formation in early 2011, RAMPS has continued the fine Appalachian tradition of using direct action to stop strip mining. RAMPS helped organize last June's March on Blair Mountain, a five-day walk to the site of the largest armed labor insurrection in United States history, which is slated to be mountaintop removal mined. Later that summer, RAMPS executed a tree sit on Coal River Mountain that, stretching to the 30-day mark, is now the longest lasting sit east of the Mississippi. This spring, they worked with a coalition of groups, including Greenpeace and Mountain Justice, to block a coal train in North Carolina.

The Mountain Mobilization represents an escalation for the RAMPS Campaign and the movement to end strip mining in Appalachia. As Tim DeChristopher pointed out, it is sustained mass action that transforms a human crisis into a political crisis which forces action from an unwilling government. This mobilization is a step towards more sustained, ongoing mass civil resistance on strip mines that the RAMPS Campaign, affiliated groups and allies hope to organize next spring.

To achieve this goal, RAMPS activists realized a bigger coalition was needed. In addition to joining with others fighting extraction, anti-strip mining activists have been building relationships with the Occupy movement and others focused on economic justice. The movement to end strip mining in Appalachia has tactical and ideological links with Occupy; it too focused on issues of economic inequality, which are at the root of strip mining and the struggle against it. Organizers from OWS came to the meeting at Mountain Justice Spring Break and many more are coming to the Mobilization.

West Virginia and the other Appalachian states where mountaintop removal occurs -- Kentucky, Tennessee and Virginia -- have a long history of economic and political domination by the coal industry. Absentee landholders own much of the mountainscape of southern West Virginia. The coal industry has a vast amount of control within the state government, paving the way for egregious environmental impacts at the expense of the state's communities.

Coal companies have long blamed the EPA and environmental groups for destroying the industry, but have recently admitted that diminishing resources are a key part of the decline. Arch Coal, one of the main players in the central Appalachian coal market, recently closed a strip mine in Webster County and laid off 122 workers. The Annual Energy Outlook 2012, produced by the U.S. Energy Information Administration, shows central Appalachian coal production declining up to 60 percent by the year 2020. Even West Virginia Senator Jay Rockefeller, who has toed the coal industry line over the past several decades, recently criticized industry leaders for their unwillingness to embrace changes. In Congress, Dennis Kucinich of Ohio and Louise Slaughter of New York, have introduced the Appalachian Communities Health Emergency Act. This bill would put a moratorium on mountaintop removal permits until health studies are conducted by the Department of Health and Human Services.

"King Coal is feeling the pressure like never before, and that means this is the most important time to ramp up resistance," says Junior Walk, an organizer and lifelong southern West Virginian. "Now we decide if we let the coal industry strip it all before deserting Appalachia or if we send them packing while we still have mountains."

And if the activists organizing the Mountain Mobilization, the participants attending it and their allies across the country keep the pressure on, it seems a lot more likely that Appalachia will still have its mountains.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

When she isn't busy fighting fracking or organizing communities, Deirdre Lally teaches free health and nutrition classes in rural northeastern Pennsylvania. On Lally's commute, she passes dozens of gas operation trucks and a number of active strip mines.

"While teaching children and seniors how to stay healthy, I look out the window of the classroom and I see nothing but strip mines surrounding the town," Lally shared in a meeting between activists fighting mountaintop removal and fracking this past spring. "Poison is running into the streams and water tables and coal dust is in the air. How is a population to be healthy when extractive industries are taking over their towns?"

Lally was at Mountain Justice Spring Break, an annual training camp for anti-mountaintop removal activists. For the past several years, students, community members and activists have gathered together each spring to share skills and fight mountaintop removal, an extremely destructive form of strip mining that scrapes off the top of mountains to get to the coal seams below. Since the 1990s, a growing coalition of activists have engaged in organized resistance to mountaintop removal, using tactics as diverse as media campaigns, direct actions and lobbying.

In a region that stretches from New York to Ohio, a geologic formation called the Marcellus Shale has become a new hot spot of environmental injustice. There, gas companies are using a process called hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, which can crack the water table and lead to groundwater contamination, among other effects. In rural Pennsylvania, where Lally lives and works, gas companies are paying off landowners to frack on their property.

This year, Mountain Justice Spring Break was located in northern West Virginia, where fracking is currently wreaking havoc upon the landscape. The intention of the location was to bring activists fighting mountaintop removal in Appalachia and fracking in the Marcellus Shale region together to share skills, strategies and experiences. The camp was an early step towards a larger vision: to turn the dozens of fights against resource extraction across the country into a unified movement for land, water and health.

Beginning in late May, strategizing and discussion grew into a plethora of actions against coal, fracking and other extractive industries. These actions have included a lock down to a coal barge on a West Virginia river and two blockades of wastewater injection wells in Ohio. In central Pennsylvania, Earth First! activists at the Moshannon State Forest blockaded a road to a gas rig, leading to the first shut down of a fracking site in United States' history. Much more is planned this summer. In August, Coal Export Action will set up camp at the state Capitol in Helena, Montana to oppose the Otter Creek Mine and other proposed mining projects in Montana and Wyoming. The national anti-fracking movement is coming together to Stop The Frack Attack in D.C., while in north Texas, citizens are preparing to blockade the Keystone XL pipeline. Taken as a whole, the actions this summer have been nicknamed the National Uprising Against Extraction.

The mobilization is being organized by the RAMPS (Radical Action for Mountain People's Survival) Campaign. Since its formation in early 2011, RAMPS has continued the fine Appalachian tradition of using direct action to stop strip mining. RAMPS helped organize last June's March on Blair Mountain, a five-day walk to the site of the largest armed labor insurrection in United States history, which is slated to be mountaintop removal mined. Later that summer, RAMPS executed a tree sit on Coal River Mountain that, stretching to the 30-day mark, is now the longest lasting sit east of the Mississippi. This spring, they worked with a coalition of groups, including Greenpeace and Mountain Justice, to block a coal train in North Carolina.

The Mountain Mobilization represents an escalation for the RAMPS Campaign and the movement to end strip mining in Appalachia. As Tim DeChristopher pointed out, it is sustained mass action that transforms a human crisis into a political crisis which forces action from an unwilling government. This mobilization is a step towards more sustained, ongoing mass civil resistance on strip mines that the RAMPS Campaign, affiliated groups and allies hope to organize next spring.

To achieve this goal, RAMPS activists realized a bigger coalition was needed. In addition to joining with others fighting extraction, anti-strip mining activists have been building relationships with the Occupy movement and others focused on economic justice. The movement to end strip mining in Appalachia has tactical and ideological links with Occupy; it too focused on issues of economic inequality, which are at the root of strip mining and the struggle against it. Organizers from OWS came to the meeting at Mountain Justice Spring Break and many more are coming to the Mobilization.

West Virginia and the other Appalachian states where mountaintop removal occurs -- Kentucky, Tennessee and Virginia -- have a long history of economic and political domination by the coal industry. Absentee landholders own much of the mountainscape of southern West Virginia. The coal industry has a vast amount of control within the state government, paving the way for egregious environmental impacts at the expense of the state's communities.

Coal companies have long blamed the EPA and environmental groups for destroying the industry, but have recently admitted that diminishing resources are a key part of the decline. Arch Coal, one of the main players in the central Appalachian coal market, recently closed a strip mine in Webster County and laid off 122 workers. The Annual Energy Outlook 2012, produced by the U.S. Energy Information Administration, shows central Appalachian coal production declining up to 60 percent by the year 2020. Even West Virginia Senator Jay Rockefeller, who has toed the coal industry line over the past several decades, recently criticized industry leaders for their unwillingness to embrace changes. In Congress, Dennis Kucinich of Ohio and Louise Slaughter of New York, have introduced the Appalachian Communities Health Emergency Act. This bill would put a moratorium on mountaintop removal permits until health studies are conducted by the Department of Health and Human Services.

"King Coal is feeling the pressure like never before, and that means this is the most important time to ramp up resistance," says Junior Walk, an organizer and lifelong southern West Virginian. "Now we decide if we let the coal industry strip it all before deserting Appalachia or if we send them packing while we still have mountains."

And if the activists organizing the Mountain Mobilization, the participants attending it and their allies across the country keep the pressure on, it seems a lot more likely that Appalachia will still have its mountains.

When she isn't busy fighting fracking or organizing communities, Deirdre Lally teaches free health and nutrition classes in rural northeastern Pennsylvania. On Lally's commute, she passes dozens of gas operation trucks and a number of active strip mines.

"While teaching children and seniors how to stay healthy, I look out the window of the classroom and I see nothing but strip mines surrounding the town," Lally shared in a meeting between activists fighting mountaintop removal and fracking this past spring. "Poison is running into the streams and water tables and coal dust is in the air. How is a population to be healthy when extractive industries are taking over their towns?"

Lally was at Mountain Justice Spring Break, an annual training camp for anti-mountaintop removal activists. For the past several years, students, community members and activists have gathered together each spring to share skills and fight mountaintop removal, an extremely destructive form of strip mining that scrapes off the top of mountains to get to the coal seams below. Since the 1990s, a growing coalition of activists have engaged in organized resistance to mountaintop removal, using tactics as diverse as media campaigns, direct actions and lobbying.

In a region that stretches from New York to Ohio, a geologic formation called the Marcellus Shale has become a new hot spot of environmental injustice. There, gas companies are using a process called hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, which can crack the water table and lead to groundwater contamination, among other effects. In rural Pennsylvania, where Lally lives and works, gas companies are paying off landowners to frack on their property.

This year, Mountain Justice Spring Break was located in northern West Virginia, where fracking is currently wreaking havoc upon the landscape. The intention of the location was to bring activists fighting mountaintop removal in Appalachia and fracking in the Marcellus Shale region together to share skills, strategies and experiences. The camp was an early step towards a larger vision: to turn the dozens of fights against resource extraction across the country into a unified movement for land, water and health.

Beginning in late May, strategizing and discussion grew into a plethora of actions against coal, fracking and other extractive industries. These actions have included a lock down to a coal barge on a West Virginia river and two blockades of wastewater injection wells in Ohio. In central Pennsylvania, Earth First! activists at the Moshannon State Forest blockaded a road to a gas rig, leading to the first shut down of a fracking site in United States' history. Much more is planned this summer. In August, Coal Export Action will set up camp at the state Capitol in Helena, Montana to oppose the Otter Creek Mine and other proposed mining projects in Montana and Wyoming. The national anti-fracking movement is coming together to Stop The Frack Attack in D.C., while in north Texas, citizens are preparing to blockade the Keystone XL pipeline. Taken as a whole, the actions this summer have been nicknamed the National Uprising Against Extraction.

The mobilization is being organized by the RAMPS (Radical Action for Mountain People's Survival) Campaign. Since its formation in early 2011, RAMPS has continued the fine Appalachian tradition of using direct action to stop strip mining. RAMPS helped organize last June's March on Blair Mountain, a five-day walk to the site of the largest armed labor insurrection in United States history, which is slated to be mountaintop removal mined. Later that summer, RAMPS executed a tree sit on Coal River Mountain that, stretching to the 30-day mark, is now the longest lasting sit east of the Mississippi. This spring, they worked with a coalition of groups, including Greenpeace and Mountain Justice, to block a coal train in North Carolina.

The Mountain Mobilization represents an escalation for the RAMPS Campaign and the movement to end strip mining in Appalachia. As Tim DeChristopher pointed out, it is sustained mass action that transforms a human crisis into a political crisis which forces action from an unwilling government. This mobilization is a step towards more sustained, ongoing mass civil resistance on strip mines that the RAMPS Campaign, affiliated groups and allies hope to organize next spring.

To achieve this goal, RAMPS activists realized a bigger coalition was needed. In addition to joining with others fighting extraction, anti-strip mining activists have been building relationships with the Occupy movement and others focused on economic justice. The movement to end strip mining in Appalachia has tactical and ideological links with Occupy; it too focused on issues of economic inequality, which are at the root of strip mining and the struggle against it. Organizers from OWS came to the meeting at Mountain Justice Spring Break and many more are coming to the Mobilization.

West Virginia and the other Appalachian states where mountaintop removal occurs -- Kentucky, Tennessee and Virginia -- have a long history of economic and political domination by the coal industry. Absentee landholders own much of the mountainscape of southern West Virginia. The coal industry has a vast amount of control within the state government, paving the way for egregious environmental impacts at the expense of the state's communities.

Coal companies have long blamed the EPA and environmental groups for destroying the industry, but have recently admitted that diminishing resources are a key part of the decline. Arch Coal, one of the main players in the central Appalachian coal market, recently closed a strip mine in Webster County and laid off 122 workers. The Annual Energy Outlook 2012, produced by the U.S. Energy Information Administration, shows central Appalachian coal production declining up to 60 percent by the year 2020. Even West Virginia Senator Jay Rockefeller, who has toed the coal industry line over the past several decades, recently criticized industry leaders for their unwillingness to embrace changes. In Congress, Dennis Kucinich of Ohio and Louise Slaughter of New York, have introduced the Appalachian Communities Health Emergency Act. This bill would put a moratorium on mountaintop removal permits until health studies are conducted by the Department of Health and Human Services.

"King Coal is feeling the pressure like never before, and that means this is the most important time to ramp up resistance," says Junior Walk, an organizer and lifelong southern West Virginian. "Now we decide if we let the coal industry strip it all before deserting Appalachia or if we send them packing while we still have mountains."

And if the activists organizing the Mountain Mobilization, the participants attending it and their allies across the country keep the pressure on, it seems a lot more likely that Appalachia will still have its mountains.