SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

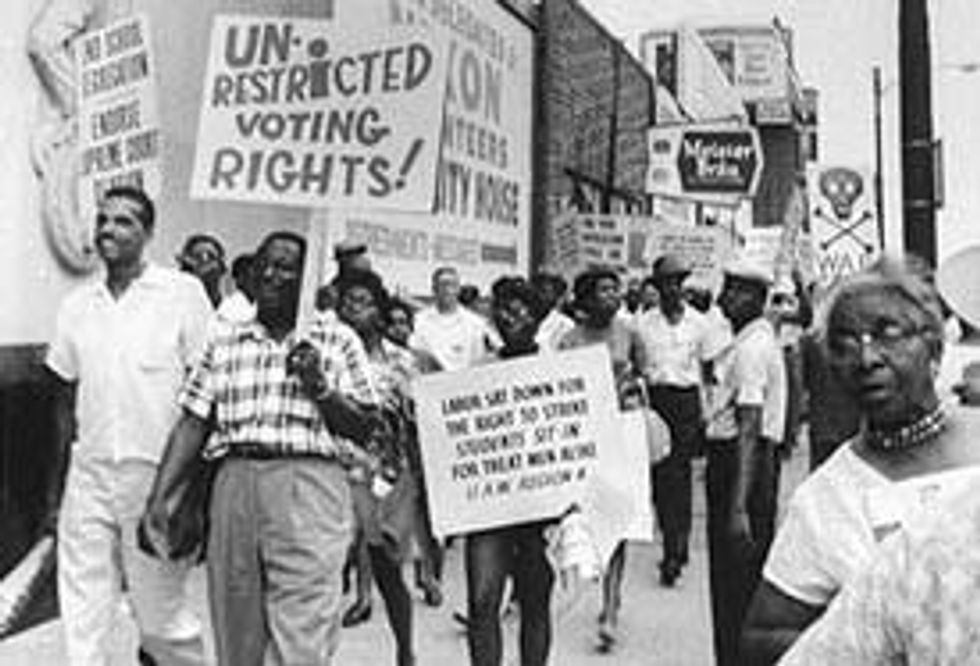

The story of American politics is, as much as anything else, a story of continuing struggle over the right to vote. After beginning as a system controlled by property-owning white men, the nation's electorate has slowly, fitfully expanded to include women, the poor and descendents of slaves, over the frequently violent resistance of conservative forces

The story of American politics is, as much as anything else, a story of continuing struggle over the right to vote. After beginning as a system controlled by property-owning white men, the nation's electorate has slowly, fitfully expanded to include women, the poor and descendents of slaves, over the frequently violent resistance of conservative forces

Florida--a key swing state in recent presidential elections--is the poster child for rolling back voting rights. Right wing politicians there have not only reduced early voting but also made it harder for ex-felons to regain their right to vote and restricted groups like the League of Women Voters from helping people register. (That last measure was struck down by a federal judge, but not before it hampered registration efforts this election season.) Sunshine State officials have also been trying to purge as many as 182,000 alleged non-citizens from its voter rolls, even though investigations have shown that at least 20 percent of the targeted voters are, in fact, citizens.

The stated purpose of the new restrictions on voting--reducing fraud--flies in the face of reality. Study after study shows voter fraud is vanishingly rare. The real fraud here is the voter ID laws themselves, which pretend to be about electoral integrity when they're really about skewing election outcomes. To understand the real reasons for them, you don't have to look any further than the main force behind them: the American Legislative Exchange Council.

ALEC is essentially a membership group for corporations that brings state legislators and industry lobbyists together to write model state laws. Its wide-ranging agenda includes making it easier for companies to hide the chemicals used in fracking operations, repealing minimum wage laws and reducing funding for public transportation.

Voter ID laws fit right in with those sorts of goals. By making it as difficult as possible for low-income people to vote, the corporate-funded right wing makes it easier to pass unpopular, industry-friendly legislation.

And we're not talking about disenfranchising only a handful of people. Even leaving aside early voting and other issues, requiring IDs to vote affects a large chunk of the population. According to the Brennan Center for Justice, as many as 10 percent of eligible voters don't have photo IDs. Those that don't are more likely to be seniors, people with disabilities, low-income people, students or people of color.

It's bad enough that many people without a drivers' license or passport are deterred by the shear hassle of getting a photo ID, or by not knowing they'll need one. What's even more disturbing is that many people who are willing to go to great lengths to vote are still being turned away under new ID laws. In Pennsylvania, one of many people in that position is Wilola Lee. Lee, 59, has been voting for the past 40 years. Now, under the state's new law, she's unable to get the identification she needs because she can't get her birth certificate from Georgia, where she was born. Lee has spent 10 years and hundreds of dollars trying to get the documentation, but she's been unsuccessful.

If new laws represent an attack on the rights of individual voters like Lee, they're just as much of a problem for the quality of the nation's political life. Already, the likelihood that Americans will vote is closely tied to their income levels. In the 2008 election, 52 percent of people with family incomes under $20,000 voted. Among those with incomes over $100,000, 80 percent did.

The issue of who votes is often put in partisan terms, and it's true that the new voter restrictions, uniformly passed by Republican-controlled state legislatures, mostly affect groups that lean toward Democrats. But the issue goes much deeper. The correlation between income and voter turnout means that the wealthier people are, the more they matter to politicians. And that's before even considering the power of campaign donations.

Throughout the nation's history, voting rights have only expanded when people joined together and demanded it. Every time, they've had to fight a powerful backlash from conservative forces. Women's suffrage was met with pamphleteers decrying the cause as "anti-female, anti-family, and anti-American." Black voters in the 1890s and afterward faced the organized terrorism of lynch mobs.

The expansion of voting rights in the face of backlash should give us hope for the future. In recent years, Election-Day registration and expanded early voting have broadened the electoral base in the states where they've been tried. And there are other ways to broaden it even more. Nations that make Election Day a holiday, or streamline registration and voting into a single step, get more participation. And other nations have plenty to teach us. An international study of the percentage of voting-age people who turned out to vote between 1945 and 2000 put the U.S. in 138th place.

Advocates of broader political participation have always had to battle against forces that want to make the government less accountable to the governed. The American right's current efforts to suppress the vote are just the latest installment in its seemingly never-ending war on democracy.

Political revenge. Mass deportations. Project 2025. Unfathomable corruption. Attacks on Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. Pardons for insurrectionists. An all-out assault on democracy. Republicans in Congress are scrambling to give Trump broad new powers to strip the tax-exempt status of any nonprofit he doesn’t like by declaring it a “terrorist-supporting organization.” Trump has already begun filing lawsuits against news outlets that criticize him. At Common Dreams, we won’t back down, but we must get ready for whatever Trump and his thugs throw at us. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. By donating today, please help us fight the dangers of a second Trump presidency. |

The story of American politics is, as much as anything else, a story of continuing struggle over the right to vote. After beginning as a system controlled by property-owning white men, the nation's electorate has slowly, fitfully expanded to include women, the poor and descendents of slaves, over the frequently violent resistance of conservative forces

Florida--a key swing state in recent presidential elections--is the poster child for rolling back voting rights. Right wing politicians there have not only reduced early voting but also made it harder for ex-felons to regain their right to vote and restricted groups like the League of Women Voters from helping people register. (That last measure was struck down by a federal judge, but not before it hampered registration efforts this election season.) Sunshine State officials have also been trying to purge as many as 182,000 alleged non-citizens from its voter rolls, even though investigations have shown that at least 20 percent of the targeted voters are, in fact, citizens.

The stated purpose of the new restrictions on voting--reducing fraud--flies in the face of reality. Study after study shows voter fraud is vanishingly rare. The real fraud here is the voter ID laws themselves, which pretend to be about electoral integrity when they're really about skewing election outcomes. To understand the real reasons for them, you don't have to look any further than the main force behind them: the American Legislative Exchange Council.

ALEC is essentially a membership group for corporations that brings state legislators and industry lobbyists together to write model state laws. Its wide-ranging agenda includes making it easier for companies to hide the chemicals used in fracking operations, repealing minimum wage laws and reducing funding for public transportation.

Voter ID laws fit right in with those sorts of goals. By making it as difficult as possible for low-income people to vote, the corporate-funded right wing makes it easier to pass unpopular, industry-friendly legislation.

And we're not talking about disenfranchising only a handful of people. Even leaving aside early voting and other issues, requiring IDs to vote affects a large chunk of the population. According to the Brennan Center for Justice, as many as 10 percent of eligible voters don't have photo IDs. Those that don't are more likely to be seniors, people with disabilities, low-income people, students or people of color.

It's bad enough that many people without a drivers' license or passport are deterred by the shear hassle of getting a photo ID, or by not knowing they'll need one. What's even more disturbing is that many people who are willing to go to great lengths to vote are still being turned away under new ID laws. In Pennsylvania, one of many people in that position is Wilola Lee. Lee, 59, has been voting for the past 40 years. Now, under the state's new law, she's unable to get the identification she needs because she can't get her birth certificate from Georgia, where she was born. Lee has spent 10 years and hundreds of dollars trying to get the documentation, but she's been unsuccessful.

If new laws represent an attack on the rights of individual voters like Lee, they're just as much of a problem for the quality of the nation's political life. Already, the likelihood that Americans will vote is closely tied to their income levels. In the 2008 election, 52 percent of people with family incomes under $20,000 voted. Among those with incomes over $100,000, 80 percent did.

The issue of who votes is often put in partisan terms, and it's true that the new voter restrictions, uniformly passed by Republican-controlled state legislatures, mostly affect groups that lean toward Democrats. But the issue goes much deeper. The correlation between income and voter turnout means that the wealthier people are, the more they matter to politicians. And that's before even considering the power of campaign donations.

Throughout the nation's history, voting rights have only expanded when people joined together and demanded it. Every time, they've had to fight a powerful backlash from conservative forces. Women's suffrage was met with pamphleteers decrying the cause as "anti-female, anti-family, and anti-American." Black voters in the 1890s and afterward faced the organized terrorism of lynch mobs.

The expansion of voting rights in the face of backlash should give us hope for the future. In recent years, Election-Day registration and expanded early voting have broadened the electoral base in the states where they've been tried. And there are other ways to broaden it even more. Nations that make Election Day a holiday, or streamline registration and voting into a single step, get more participation. And other nations have plenty to teach us. An international study of the percentage of voting-age people who turned out to vote between 1945 and 2000 put the U.S. in 138th place.

Advocates of broader political participation have always had to battle against forces that want to make the government less accountable to the governed. The American right's current efforts to suppress the vote are just the latest installment in its seemingly never-ending war on democracy.

The story of American politics is, as much as anything else, a story of continuing struggle over the right to vote. After beginning as a system controlled by property-owning white men, the nation's electorate has slowly, fitfully expanded to include women, the poor and descendents of slaves, over the frequently violent resistance of conservative forces

Florida--a key swing state in recent presidential elections--is the poster child for rolling back voting rights. Right wing politicians there have not only reduced early voting but also made it harder for ex-felons to regain their right to vote and restricted groups like the League of Women Voters from helping people register. (That last measure was struck down by a federal judge, but not before it hampered registration efforts this election season.) Sunshine State officials have also been trying to purge as many as 182,000 alleged non-citizens from its voter rolls, even though investigations have shown that at least 20 percent of the targeted voters are, in fact, citizens.

The stated purpose of the new restrictions on voting--reducing fraud--flies in the face of reality. Study after study shows voter fraud is vanishingly rare. The real fraud here is the voter ID laws themselves, which pretend to be about electoral integrity when they're really about skewing election outcomes. To understand the real reasons for them, you don't have to look any further than the main force behind them: the American Legislative Exchange Council.

ALEC is essentially a membership group for corporations that brings state legislators and industry lobbyists together to write model state laws. Its wide-ranging agenda includes making it easier for companies to hide the chemicals used in fracking operations, repealing minimum wage laws and reducing funding for public transportation.

Voter ID laws fit right in with those sorts of goals. By making it as difficult as possible for low-income people to vote, the corporate-funded right wing makes it easier to pass unpopular, industry-friendly legislation.

And we're not talking about disenfranchising only a handful of people. Even leaving aside early voting and other issues, requiring IDs to vote affects a large chunk of the population. According to the Brennan Center for Justice, as many as 10 percent of eligible voters don't have photo IDs. Those that don't are more likely to be seniors, people with disabilities, low-income people, students or people of color.

It's bad enough that many people without a drivers' license or passport are deterred by the shear hassle of getting a photo ID, or by not knowing they'll need one. What's even more disturbing is that many people who are willing to go to great lengths to vote are still being turned away under new ID laws. In Pennsylvania, one of many people in that position is Wilola Lee. Lee, 59, has been voting for the past 40 years. Now, under the state's new law, she's unable to get the identification she needs because she can't get her birth certificate from Georgia, where she was born. Lee has spent 10 years and hundreds of dollars trying to get the documentation, but she's been unsuccessful.

If new laws represent an attack on the rights of individual voters like Lee, they're just as much of a problem for the quality of the nation's political life. Already, the likelihood that Americans will vote is closely tied to their income levels. In the 2008 election, 52 percent of people with family incomes under $20,000 voted. Among those with incomes over $100,000, 80 percent did.

The issue of who votes is often put in partisan terms, and it's true that the new voter restrictions, uniformly passed by Republican-controlled state legislatures, mostly affect groups that lean toward Democrats. But the issue goes much deeper. The correlation between income and voter turnout means that the wealthier people are, the more they matter to politicians. And that's before even considering the power of campaign donations.

Throughout the nation's history, voting rights have only expanded when people joined together and demanded it. Every time, they've had to fight a powerful backlash from conservative forces. Women's suffrage was met with pamphleteers decrying the cause as "anti-female, anti-family, and anti-American." Black voters in the 1890s and afterward faced the organized terrorism of lynch mobs.

The expansion of voting rights in the face of backlash should give us hope for the future. In recent years, Election-Day registration and expanded early voting have broadened the electoral base in the states where they've been tried. And there are other ways to broaden it even more. Nations that make Election Day a holiday, or streamline registration and voting into a single step, get more participation. And other nations have plenty to teach us. An international study of the percentage of voting-age people who turned out to vote between 1945 and 2000 put the U.S. in 138th place.

Advocates of broader political participation have always had to battle against forces that want to make the government less accountable to the governed. The American right's current efforts to suppress the vote are just the latest installment in its seemingly never-ending war on democracy.