Sep 07, 2012

All this talk today about poverty got us wondering just how many people in America live below the poverty line," anchor Scott Pelley announced on the CBS Evening News (2/1/12). By "all this talk," Pelley was referring to less than 200 words, in a report CBS had just aired on GOP candidate Mitt Romney's missteps, that discussed Romney's remark that he wasn't "concerned about the very poor."

Though the brief story was actually about the political horse race, it apparently struck Pelley as an unusual amount of focus on poverty. And, sadly, he was right.

Poverty as an issue is nearly invisible in U.S. media coverage of the 2012 election, a new FAIR study has found--even though what candidates plan to do about an alarmingly growing poverty rate would seem to be a ripe topic for discussion in campaign coverage.

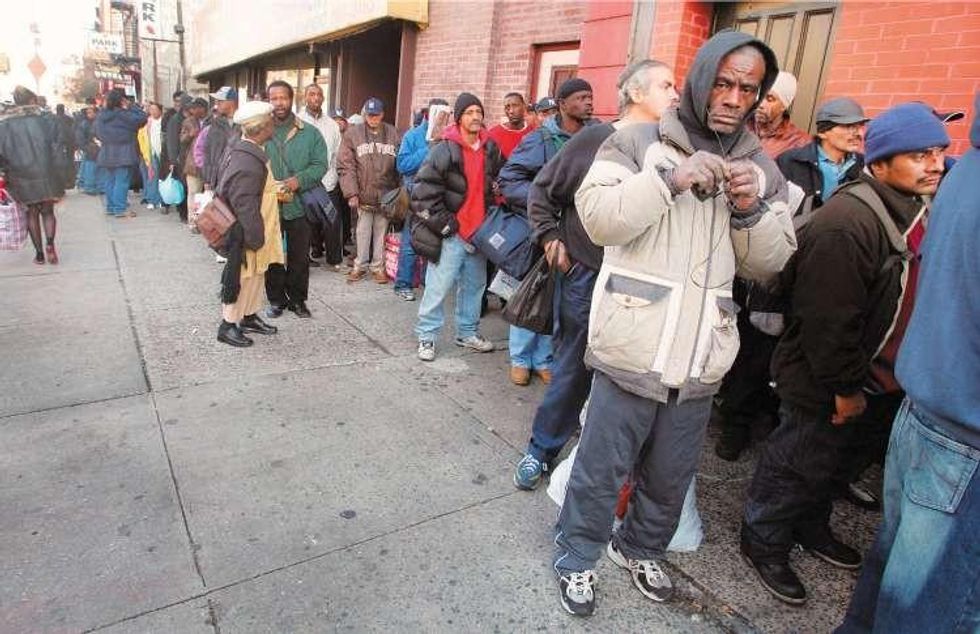

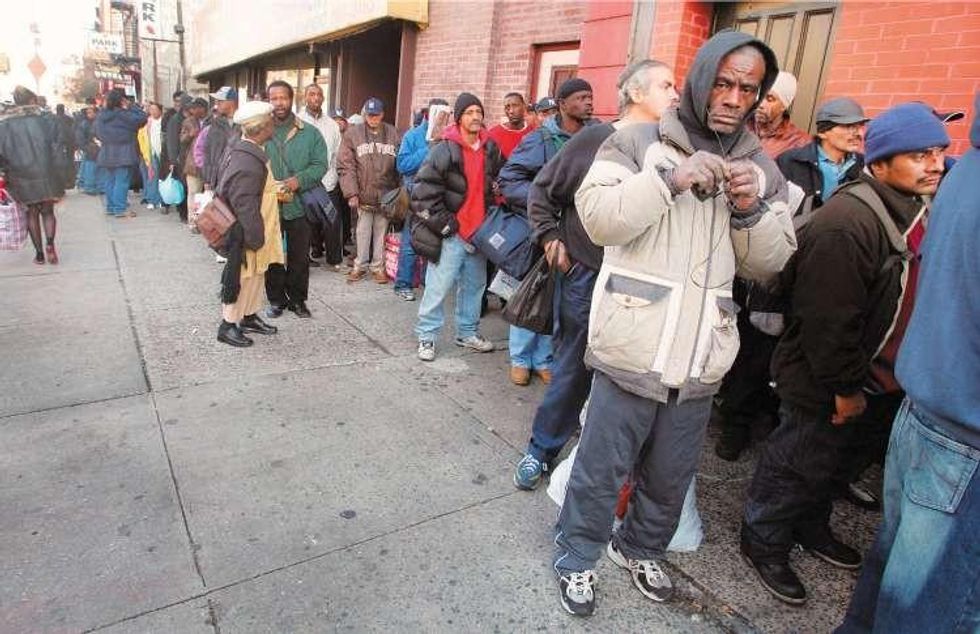

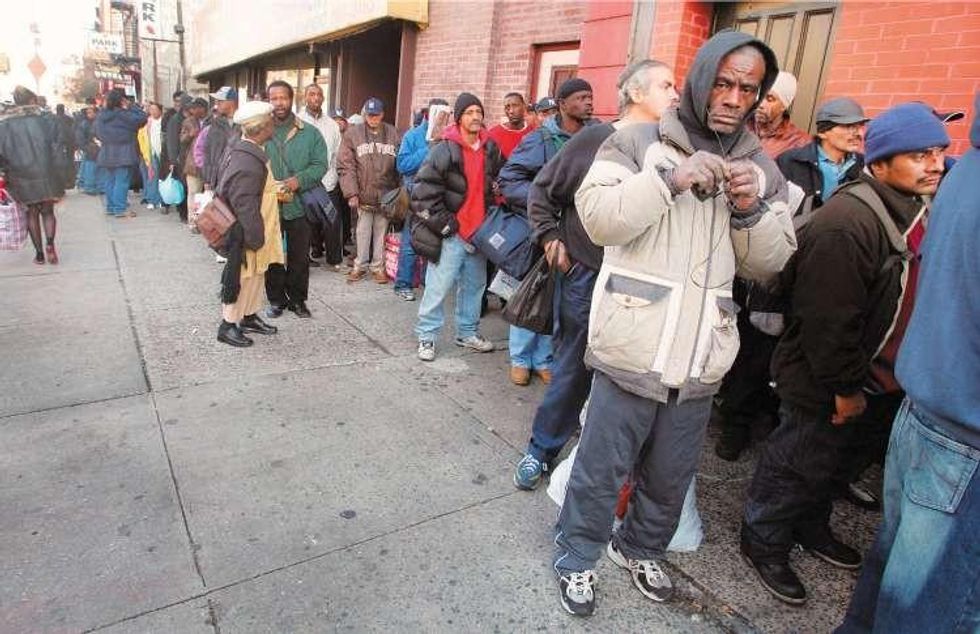

Even before the economic downturn made the poverty picture significantly worse in the United States, the Urban Institute reported that half of all Americans (51 percent) experience poverty at some time before age 65 (Urban Institute, 9/10/09).

According to the U.S. Census Bureau's 2011 report (9/11), poverty in 2010 was at a 19-year high, affecting 46 million people, or 15.1 percent of the population. That's up sharply from 11.3 percent in 2000, and 12.5 percent in 2007. And several groups feel the effects of poverty at a much higher rate than the national average. According to the 2011 census, more than one in five children (22 percent) live in poverty, as do more than a quarter of all blacks (27 percent) and Latinos (26 percent). A 2011 Brookings Institution study (9/13/11) predicted that as many as 10 million additional Americans will join the ranks of the poor by 2014.

The Census Bureau counts a single person under 65 as being in poverty if they make less than $11,702; for a family of four, the cut-off is $22,314 a year. These thresholds--calculated since the 1960s simply by multiplying estimated food costs by three--have been criticized for failing to account for the increased costs of necessities like housing, transportation and childcare, so the official poverty rates may grossly understate the number of families actually living in poverty. The National Center for Children in Poverty at Columbia University (6/08), for example, estimates that "families typically need an income of at least twice the official poverty level ($42,400 for a family of four) to meet basic needs."

A recent AP report (7/23/12) summarized the dire predictions of economists, academics and think tanks about poverty's current trajectory: "The ranks of America's poor are on track to climb to levels unseen in nearly half a century, erasing gains from the war on poverty in the 1960s amid a weak economy and fraying government safety net."

To see how this crisis is addressed in coverage of the 2012 presidential election, Extra! looked at six months of campaign coverage (1/1/12-6/23/12) by eight prominent news outlets: CBS Evening News, ABC World News, NBC Nightly News, PBSNewsHour and NPR's All Things Considered, and the print editions of the New York Times, Washington Post and Newsweek. Using the Nexis news database, the study counted campaign-related stories, both news reports and commentary, that were substantively about poverty (i.e., mentioning causes, referring to proposed solutions and so forth), as well as campaign stories that mentioned poverty in passing or less substantial ways.

Substantive mentions of the issue included stories like Jia Lynn Yang's informative news article in the Washington Post (4/14/12), which addressed the presidential candidates' policies toward the poor. Yang reported on Romney's and Obama's fundamentally different proposals for how drastic income inequality might be alleviated, but also noted that both candidates tend to court the middle class above all else.

Stories not counted as substantive coverage included largely reactive reports about candidates' "gaffes" or campaign speeches, like the ABC World News story (4/3/12) reporting Romney's soundbite: "I go across the country and I'm talking to single moms, for instance, 30 percent of single moms are living in poverty now under this president." Rather than prompting further analysis of the issue of female poverty, the soundbite merely served to illustrate how both candidates are fighting to win over the "key group" of women voters.

A New York Times editorial (2/2/12) that reacted to Romney's statement about not being concerned about the "very poor," however, was counted as substantive, because it put the remark in the context of poverty numbers and offered an argument about the impact of Romney's policy proposals:

Mr. Romney tried to explain that he was focused on middle-income Americans because the poor--now a full 15 percent of the population--already have a government safety net. He failed to mention, of course, that his policies, and those of his fellow Republicans in Washington, would drive more people into that net--while at the same time shredding it.

Despite its widely experienced impact, FAIR's study found poverty barely registers as a campaign issue. Just 17 of the 10,489 campaign stories studied (0.2 percent) addressed poverty in a substantive way. Moreover, none of the eight outlets included a substantive discussion of poverty in as much as 1 percent of its campaign stories.

Discussions of poverty in campaign coverage were so rare that PBSNewsHour had the highest percentage of its campaign stories addressing poverty--with a single story, 0.8 percent of its total. ABC World News, NBC Nightly News, NPR's All Things Considered, and Newsweek ran no campaign stories substantively discussing poverty.

The New York Times included substantive information about poverty in just 0.2 percent of its campaign stories and opinion pieces--placing it third out of the eight outlets, behind PBS and CBS.

By contrast with other issues that have received wider attention in recent campaign coverage, "poverty" was mentioned at all, with or (most often) without substantive discussion, in just 3 percent of campaign stories (309 stories) in the eight outlets. This compares to "deficit" and "debt," which were mentioned about six times as often, in 18 percent (1,848) of election stories.

Even throwing a wider net, to include stories that mentioned "poverty," "low income," "homeless," "welfare" or "food stamps," turned up just 945 pieces, 10 percent of total election stories--still well below the rate at which "debt" and "deficit" were mentioned.

Previous FAIR reports and Extra! articles (7-8/06, 9-10/07) have discussed reasons journalists find the subject of poverty unappealing: "For one, journalists like a story to have a resolution, preferably a happy one"--unlike poverty, which they see as "a sad, intractable fact of life, a story that never gets better and generates little interest or news." Perhaps more importantly, advertisers aren't fond of poverty stories, which don't provide a good media environment for their commercials.

But there are additional reasons journalists avoid raising poverty in campaign coverage.

Mainstream reporters often say they can't raise an issue unless it is first brooked by a politician or official (Extra!, 11-12/04). As Washington Post columnist David Ignatius (4/27/04) explained the astonishing lack of a media debate in the lead-up to the Iraq War:

In a sense, the media were victims of their own professionalism. Because there was little criticism of the war from prominent Democrats and foreign policy analysts, journalistic rules meant we shouldn't create a debate on our own.

It's worth noting that these "rules" are selectively applied. For instance, following mass murder at a movie theater in Aurora, Colorado, many news outlets featured at least some discussion of gun regulation, though neither major party candidate was speaking out on the subject. As the New York Times reported (7/24/12), "Neither has responded to calls for a renewed debate over how to prevent gun violence."

These rules explain why there were small flurries of stories mentioning poverty following Romney's "very poor" gaffe (2/1/12), or fellow GOP candidate Newt Gingrich's remarks calling Barack Obama the "food stamp president" (1/6/12) or proposing to have poor children work as school janitors (1/17/12).

The same journalistic standards also explain why the term "middle class," ever-present in major party candidates' stump speeches, was far more likely to be mentioned in campaign reporting than was poverty, occurring in more than twice as many stories (681), or 7 percent of campaign stories.

In the current election year, when neither the incumbent Democratic president nor any of his challengers in the GOP primary have been making poverty even a minor issue, such "rules" are relegating tens of millions of struggling citizens to virtual invisibility.

An Unconstitutional Rampage

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

© 2023 Fairness and Accuracy In Reporting (FAIR)

Steve Rendall

Steve Rendall is a FAIR contributing writer. His work has received awards from Project Censored, and has won the praise of noted journalists such as Les Payne, Molly Ivins and Garry Wills.

Mariana Garces

Mariana Garces is a journalist and former intern at Fairness and Accuracy In Reporting (FAIR).

All this talk today about poverty got us wondering just how many people in America live below the poverty line," anchor Scott Pelley announced on the CBS Evening News (2/1/12). By "all this talk," Pelley was referring to less than 200 words, in a report CBS had just aired on GOP candidate Mitt Romney's missteps, that discussed Romney's remark that he wasn't "concerned about the very poor."

Though the brief story was actually about the political horse race, it apparently struck Pelley as an unusual amount of focus on poverty. And, sadly, he was right.

Poverty as an issue is nearly invisible in U.S. media coverage of the 2012 election, a new FAIR study has found--even though what candidates plan to do about an alarmingly growing poverty rate would seem to be a ripe topic for discussion in campaign coverage.

Even before the economic downturn made the poverty picture significantly worse in the United States, the Urban Institute reported that half of all Americans (51 percent) experience poverty at some time before age 65 (Urban Institute, 9/10/09).

According to the U.S. Census Bureau's 2011 report (9/11), poverty in 2010 was at a 19-year high, affecting 46 million people, or 15.1 percent of the population. That's up sharply from 11.3 percent in 2000, and 12.5 percent in 2007. And several groups feel the effects of poverty at a much higher rate than the national average. According to the 2011 census, more than one in five children (22 percent) live in poverty, as do more than a quarter of all blacks (27 percent) and Latinos (26 percent). A 2011 Brookings Institution study (9/13/11) predicted that as many as 10 million additional Americans will join the ranks of the poor by 2014.

The Census Bureau counts a single person under 65 as being in poverty if they make less than $11,702; for a family of four, the cut-off is $22,314 a year. These thresholds--calculated since the 1960s simply by multiplying estimated food costs by three--have been criticized for failing to account for the increased costs of necessities like housing, transportation and childcare, so the official poverty rates may grossly understate the number of families actually living in poverty. The National Center for Children in Poverty at Columbia University (6/08), for example, estimates that "families typically need an income of at least twice the official poverty level ($42,400 for a family of four) to meet basic needs."

A recent AP report (7/23/12) summarized the dire predictions of economists, academics and think tanks about poverty's current trajectory: "The ranks of America's poor are on track to climb to levels unseen in nearly half a century, erasing gains from the war on poverty in the 1960s amid a weak economy and fraying government safety net."

To see how this crisis is addressed in coverage of the 2012 presidential election, Extra! looked at six months of campaign coverage (1/1/12-6/23/12) by eight prominent news outlets: CBS Evening News, ABC World News, NBC Nightly News, PBSNewsHour and NPR's All Things Considered, and the print editions of the New York Times, Washington Post and Newsweek. Using the Nexis news database, the study counted campaign-related stories, both news reports and commentary, that were substantively about poverty (i.e., mentioning causes, referring to proposed solutions and so forth), as well as campaign stories that mentioned poverty in passing or less substantial ways.

Substantive mentions of the issue included stories like Jia Lynn Yang's informative news article in the Washington Post (4/14/12), which addressed the presidential candidates' policies toward the poor. Yang reported on Romney's and Obama's fundamentally different proposals for how drastic income inequality might be alleviated, but also noted that both candidates tend to court the middle class above all else.

Stories not counted as substantive coverage included largely reactive reports about candidates' "gaffes" or campaign speeches, like the ABC World News story (4/3/12) reporting Romney's soundbite: "I go across the country and I'm talking to single moms, for instance, 30 percent of single moms are living in poverty now under this president." Rather than prompting further analysis of the issue of female poverty, the soundbite merely served to illustrate how both candidates are fighting to win over the "key group" of women voters.

A New York Times editorial (2/2/12) that reacted to Romney's statement about not being concerned about the "very poor," however, was counted as substantive, because it put the remark in the context of poverty numbers and offered an argument about the impact of Romney's policy proposals:

Mr. Romney tried to explain that he was focused on middle-income Americans because the poor--now a full 15 percent of the population--already have a government safety net. He failed to mention, of course, that his policies, and those of his fellow Republicans in Washington, would drive more people into that net--while at the same time shredding it.

Despite its widely experienced impact, FAIR's study found poverty barely registers as a campaign issue. Just 17 of the 10,489 campaign stories studied (0.2 percent) addressed poverty in a substantive way. Moreover, none of the eight outlets included a substantive discussion of poverty in as much as 1 percent of its campaign stories.

Discussions of poverty in campaign coverage were so rare that PBSNewsHour had the highest percentage of its campaign stories addressing poverty--with a single story, 0.8 percent of its total. ABC World News, NBC Nightly News, NPR's All Things Considered, and Newsweek ran no campaign stories substantively discussing poverty.

The New York Times included substantive information about poverty in just 0.2 percent of its campaign stories and opinion pieces--placing it third out of the eight outlets, behind PBS and CBS.

By contrast with other issues that have received wider attention in recent campaign coverage, "poverty" was mentioned at all, with or (most often) without substantive discussion, in just 3 percent of campaign stories (309 stories) in the eight outlets. This compares to "deficit" and "debt," which were mentioned about six times as often, in 18 percent (1,848) of election stories.

Even throwing a wider net, to include stories that mentioned "poverty," "low income," "homeless," "welfare" or "food stamps," turned up just 945 pieces, 10 percent of total election stories--still well below the rate at which "debt" and "deficit" were mentioned.

Previous FAIR reports and Extra! articles (7-8/06, 9-10/07) have discussed reasons journalists find the subject of poverty unappealing: "For one, journalists like a story to have a resolution, preferably a happy one"--unlike poverty, which they see as "a sad, intractable fact of life, a story that never gets better and generates little interest or news." Perhaps more importantly, advertisers aren't fond of poverty stories, which don't provide a good media environment for their commercials.

But there are additional reasons journalists avoid raising poverty in campaign coverage.

Mainstream reporters often say they can't raise an issue unless it is first brooked by a politician or official (Extra!, 11-12/04). As Washington Post columnist David Ignatius (4/27/04) explained the astonishing lack of a media debate in the lead-up to the Iraq War:

In a sense, the media were victims of their own professionalism. Because there was little criticism of the war from prominent Democrats and foreign policy analysts, journalistic rules meant we shouldn't create a debate on our own.

It's worth noting that these "rules" are selectively applied. For instance, following mass murder at a movie theater in Aurora, Colorado, many news outlets featured at least some discussion of gun regulation, though neither major party candidate was speaking out on the subject. As the New York Times reported (7/24/12), "Neither has responded to calls for a renewed debate over how to prevent gun violence."

These rules explain why there were small flurries of stories mentioning poverty following Romney's "very poor" gaffe (2/1/12), or fellow GOP candidate Newt Gingrich's remarks calling Barack Obama the "food stamp president" (1/6/12) or proposing to have poor children work as school janitors (1/17/12).

The same journalistic standards also explain why the term "middle class," ever-present in major party candidates' stump speeches, was far more likely to be mentioned in campaign reporting than was poverty, occurring in more than twice as many stories (681), or 7 percent of campaign stories.

In the current election year, when neither the incumbent Democratic president nor any of his challengers in the GOP primary have been making poverty even a minor issue, such "rules" are relegating tens of millions of struggling citizens to virtual invisibility.

Steve Rendall

Steve Rendall is a FAIR contributing writer. His work has received awards from Project Censored, and has won the praise of noted journalists such as Les Payne, Molly Ivins and Garry Wills.

Mariana Garces

Mariana Garces is a journalist and former intern at Fairness and Accuracy In Reporting (FAIR).

All this talk today about poverty got us wondering just how many people in America live below the poverty line," anchor Scott Pelley announced on the CBS Evening News (2/1/12). By "all this talk," Pelley was referring to less than 200 words, in a report CBS had just aired on GOP candidate Mitt Romney's missteps, that discussed Romney's remark that he wasn't "concerned about the very poor."

Though the brief story was actually about the political horse race, it apparently struck Pelley as an unusual amount of focus on poverty. And, sadly, he was right.

Poverty as an issue is nearly invisible in U.S. media coverage of the 2012 election, a new FAIR study has found--even though what candidates plan to do about an alarmingly growing poverty rate would seem to be a ripe topic for discussion in campaign coverage.

Even before the economic downturn made the poverty picture significantly worse in the United States, the Urban Institute reported that half of all Americans (51 percent) experience poverty at some time before age 65 (Urban Institute, 9/10/09).

According to the U.S. Census Bureau's 2011 report (9/11), poverty in 2010 was at a 19-year high, affecting 46 million people, or 15.1 percent of the population. That's up sharply from 11.3 percent in 2000, and 12.5 percent in 2007. And several groups feel the effects of poverty at a much higher rate than the national average. According to the 2011 census, more than one in five children (22 percent) live in poverty, as do more than a quarter of all blacks (27 percent) and Latinos (26 percent). A 2011 Brookings Institution study (9/13/11) predicted that as many as 10 million additional Americans will join the ranks of the poor by 2014.

The Census Bureau counts a single person under 65 as being in poverty if they make less than $11,702; for a family of four, the cut-off is $22,314 a year. These thresholds--calculated since the 1960s simply by multiplying estimated food costs by three--have been criticized for failing to account for the increased costs of necessities like housing, transportation and childcare, so the official poverty rates may grossly understate the number of families actually living in poverty. The National Center for Children in Poverty at Columbia University (6/08), for example, estimates that "families typically need an income of at least twice the official poverty level ($42,400 for a family of four) to meet basic needs."

A recent AP report (7/23/12) summarized the dire predictions of economists, academics and think tanks about poverty's current trajectory: "The ranks of America's poor are on track to climb to levels unseen in nearly half a century, erasing gains from the war on poverty in the 1960s amid a weak economy and fraying government safety net."

To see how this crisis is addressed in coverage of the 2012 presidential election, Extra! looked at six months of campaign coverage (1/1/12-6/23/12) by eight prominent news outlets: CBS Evening News, ABC World News, NBC Nightly News, PBSNewsHour and NPR's All Things Considered, and the print editions of the New York Times, Washington Post and Newsweek. Using the Nexis news database, the study counted campaign-related stories, both news reports and commentary, that were substantively about poverty (i.e., mentioning causes, referring to proposed solutions and so forth), as well as campaign stories that mentioned poverty in passing or less substantial ways.

Substantive mentions of the issue included stories like Jia Lynn Yang's informative news article in the Washington Post (4/14/12), which addressed the presidential candidates' policies toward the poor. Yang reported on Romney's and Obama's fundamentally different proposals for how drastic income inequality might be alleviated, but also noted that both candidates tend to court the middle class above all else.

Stories not counted as substantive coverage included largely reactive reports about candidates' "gaffes" or campaign speeches, like the ABC World News story (4/3/12) reporting Romney's soundbite: "I go across the country and I'm talking to single moms, for instance, 30 percent of single moms are living in poverty now under this president." Rather than prompting further analysis of the issue of female poverty, the soundbite merely served to illustrate how both candidates are fighting to win over the "key group" of women voters.

A New York Times editorial (2/2/12) that reacted to Romney's statement about not being concerned about the "very poor," however, was counted as substantive, because it put the remark in the context of poverty numbers and offered an argument about the impact of Romney's policy proposals:

Mr. Romney tried to explain that he was focused on middle-income Americans because the poor--now a full 15 percent of the population--already have a government safety net. He failed to mention, of course, that his policies, and those of his fellow Republicans in Washington, would drive more people into that net--while at the same time shredding it.

Despite its widely experienced impact, FAIR's study found poverty barely registers as a campaign issue. Just 17 of the 10,489 campaign stories studied (0.2 percent) addressed poverty in a substantive way. Moreover, none of the eight outlets included a substantive discussion of poverty in as much as 1 percent of its campaign stories.

Discussions of poverty in campaign coverage were so rare that PBSNewsHour had the highest percentage of its campaign stories addressing poverty--with a single story, 0.8 percent of its total. ABC World News, NBC Nightly News, NPR's All Things Considered, and Newsweek ran no campaign stories substantively discussing poverty.

The New York Times included substantive information about poverty in just 0.2 percent of its campaign stories and opinion pieces--placing it third out of the eight outlets, behind PBS and CBS.

By contrast with other issues that have received wider attention in recent campaign coverage, "poverty" was mentioned at all, with or (most often) without substantive discussion, in just 3 percent of campaign stories (309 stories) in the eight outlets. This compares to "deficit" and "debt," which were mentioned about six times as often, in 18 percent (1,848) of election stories.

Even throwing a wider net, to include stories that mentioned "poverty," "low income," "homeless," "welfare" or "food stamps," turned up just 945 pieces, 10 percent of total election stories--still well below the rate at which "debt" and "deficit" were mentioned.

Previous FAIR reports and Extra! articles (7-8/06, 9-10/07) have discussed reasons journalists find the subject of poverty unappealing: "For one, journalists like a story to have a resolution, preferably a happy one"--unlike poverty, which they see as "a sad, intractable fact of life, a story that never gets better and generates little interest or news." Perhaps more importantly, advertisers aren't fond of poverty stories, which don't provide a good media environment for their commercials.

But there are additional reasons journalists avoid raising poverty in campaign coverage.

Mainstream reporters often say they can't raise an issue unless it is first brooked by a politician or official (Extra!, 11-12/04). As Washington Post columnist David Ignatius (4/27/04) explained the astonishing lack of a media debate in the lead-up to the Iraq War:

In a sense, the media were victims of their own professionalism. Because there was little criticism of the war from prominent Democrats and foreign policy analysts, journalistic rules meant we shouldn't create a debate on our own.

It's worth noting that these "rules" are selectively applied. For instance, following mass murder at a movie theater in Aurora, Colorado, many news outlets featured at least some discussion of gun regulation, though neither major party candidate was speaking out on the subject. As the New York Times reported (7/24/12), "Neither has responded to calls for a renewed debate over how to prevent gun violence."

These rules explain why there were small flurries of stories mentioning poverty following Romney's "very poor" gaffe (2/1/12), or fellow GOP candidate Newt Gingrich's remarks calling Barack Obama the "food stamp president" (1/6/12) or proposing to have poor children work as school janitors (1/17/12).

The same journalistic standards also explain why the term "middle class," ever-present in major party candidates' stump speeches, was far more likely to be mentioned in campaign reporting than was poverty, occurring in more than twice as many stories (681), or 7 percent of campaign stories.

In the current election year, when neither the incumbent Democratic president nor any of his challengers in the GOP primary have been making poverty even a minor issue, such "rules" are relegating tens of millions of struggling citizens to virtual invisibility.

We've had enough. The 1% own and operate the corporate media. They are doing everything they can to defend the status quo, squash dissent and protect the wealthy and the powerful. The Common Dreams media model is different. We cover the news that matters to the 99%. Our mission? To inform. To inspire. To ignite change for the common good. How? Nonprofit. Independent. Reader-supported. Free to read. Free to republish. Free to share. With no advertising. No paywalls. No selling of your data. Thousands of small donations fund our newsroom and allow us to continue publishing. Can you chip in? We can't do it without you. Thank you.