SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

Marie Sklodowska Curie Metro High School is located in a hardscrabble neighborhood on Chicago's southwest side. A coal-burning power plant lies just to the north and various factories and warehouses stand on surrounding streets.

Gang violence is a serious problem in the area, and the economic crisis has hit many immigrant families hard.

Students and teachers describe the school as a safe haven, a place where, despite a severe lack of resources, teachers offer innovative lessons with real-world context and organize clubs and after-school programs on topics like literature, science, and the environment.

Curie students say they recognize the extra lengths their teachers go to in making sure they get a stimulating, top-flight education even in such trying circumstances. Hence many students and former students have spent the past few days on the picket lines with their teachers and former teachers.

"This is my family," said Nicolas Coronado, 19, a DePaul University political science student on the picket line with his former IB History teacher, Homero Penuelas. "I loved it here."

A student marching band has been helping to keep their teachers' spirits up on the picket line, and one student has even turned up each day in a hot dog costume with a sign saying "Mayor Emanuel Is a Weenie."

On Thursday morning, 2007 Curie graduate Jose Xavier Montenegro gave a younger student pointers on drumming.

"I wasn't the best student but I look up to these teachers," said Montenegro, who now works as a laborer with his own company and competes in power-lifting. "I know what it's like in those classrooms. It's jam-packed; in one class we had 42 students. One time a rat ran through the classroom. Teachers could do a lot more if they had more resources."

Students describe teachers regularly buying supplies out of their own pockets.

"It's like being in a factory and paying your own money for the parts you need to make a phone," said Curie senior Adam Cabanas, 17, standing on the picket line Thursday with senior Cheyenne Watkins. "I love my teachers. They are always there for you."

"They take money out of their own wallets for us," added Watkins, 17. "For teachers to be treated badly after they have put so much of their lives into this is not fair. [The administration] tries to make it look like teachers are hurting students. But students are hurting in the classrooms - there's no air conditioning. You have 38 students in one class."

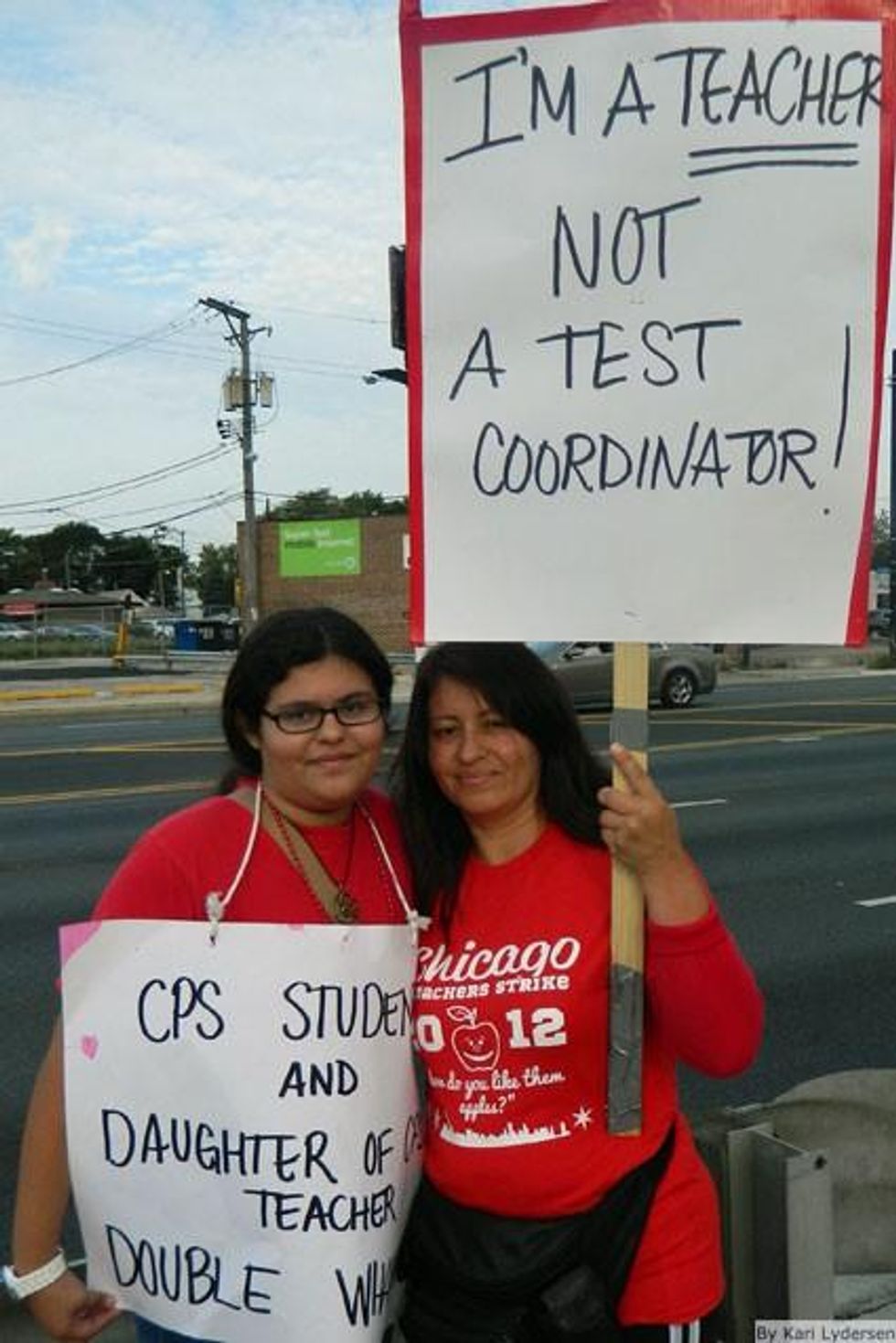

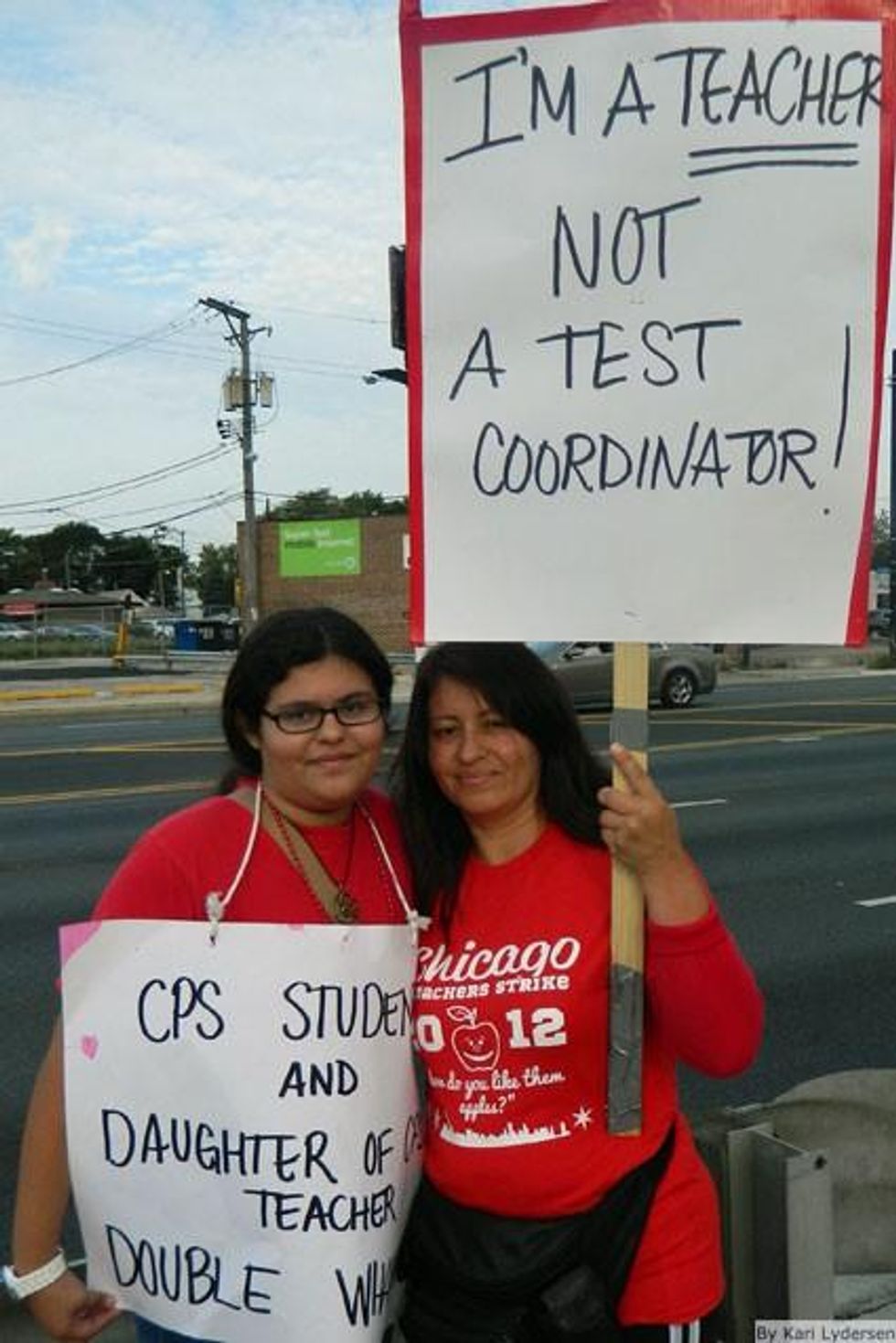

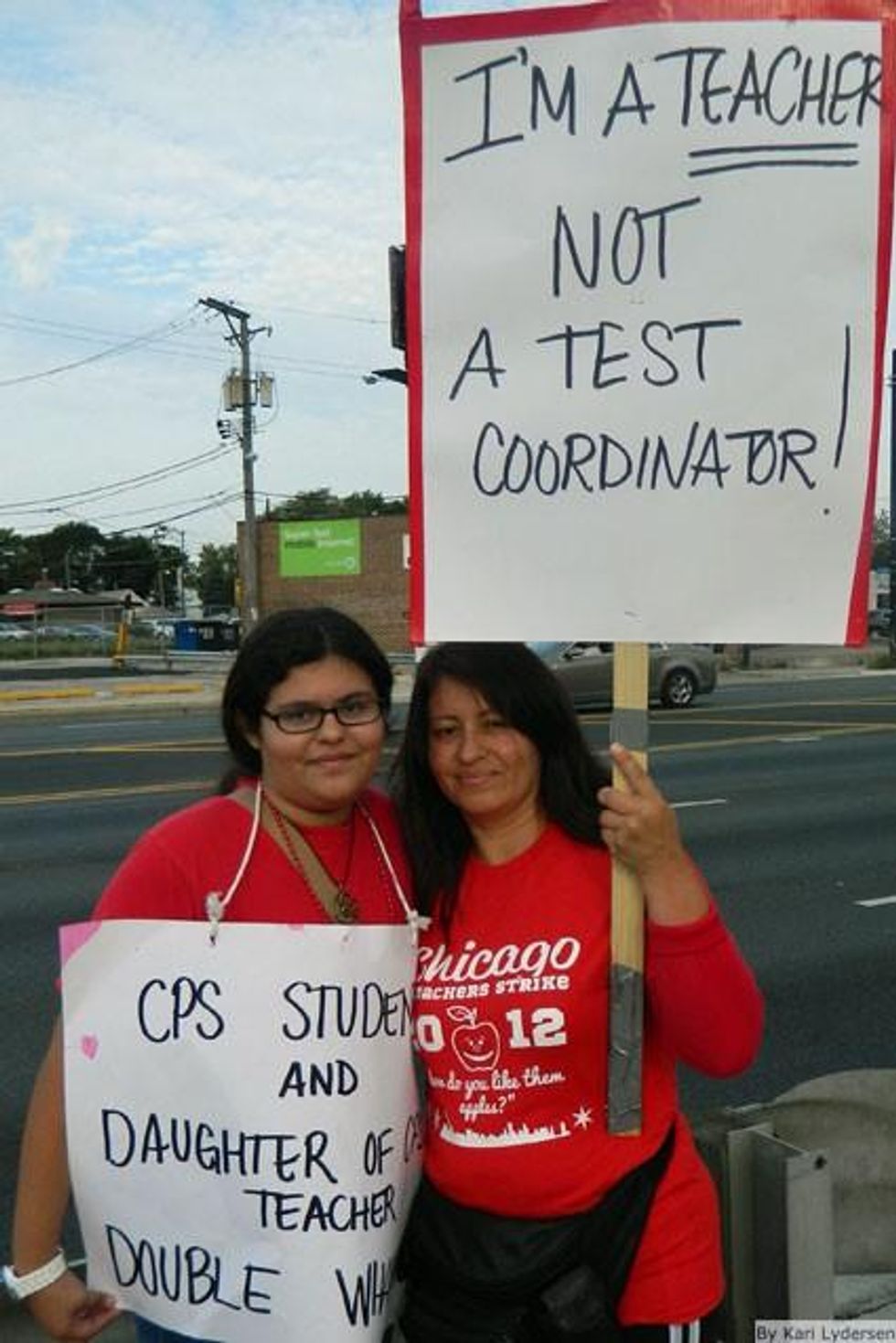

Jazmin Gonzalez, a seventh-grader at Lindblom Elementary in the nearby Englewood neighborhood, joined her mother and Curie science teacher Maricruz Gonzalez outside the school, wearing a sign around her neck saying "CPS student and daughter of CPS teacher - Double Whammy."

"It's a little scary but this has to happen for teachers to get what they need to teach us effectively, they are some of the hardest working people I've ever met in my life," said Gonzalez about the strike, noting that in her overcrowded classes there are "people sharing desks and sitting at the teacher's desk."

Karina Alcorchas, a 2012 Curie graduate, credits Curie teachers with inspiring her to pursue chemical engineering at the Illinois Institute of Technology. "It's important to give back to the teachers who have given so much to us," said Alcorchas, who earlier in the week walked picket lines with her former elementary school teachers.

Curie highlights the main reasons the teachers union opposes standardized testing used to determine merit-based pay, which the school board has backed off on, and merit-based evaluations, which the board is still demanding. (After negotiations Wednesday, both the school board and union president Karen Lewis said progress was being made and students might be back in class on Friday).

"Merit pay works only in neighborhoods where you're not dealing with the kinds of things we're dealing with here," said Penuelas. "I have students who go to work after school and work until 1 in the morning, then we start school at 7:30 am. Many are the breadwinners in their families. We try our best to help our students but these are hard things to overcome."

Rosana Enriquez, Curie's only social worker, elaborated on the challenges facing students.

"Just last week I talked to three kids whose fathers are in jail, and one whose mother had been deported and she was living with relatives, and teen mothers. That's not to mention the foster kids we serve," she said, noting that more social workers in the schools are desperately needed. "Kids are living with depression and anxiety because of the violence in the neighborhood."

Teachers at Curie, as at many public schools, often incorporate the harsh realities that their students live with into their lesson plans, an approach Penuelas noted can also apply to the strike.

"This is as prime an example as any of a civics lesson," he said. "If parents are worried about their kids being at home not getting an education, they should bring them out here. It's a lesson in democracy and power in numbers."

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

Marie Sklodowska Curie Metro High School is located in a hardscrabble neighborhood on Chicago's southwest side. A coal-burning power plant lies just to the north and various factories and warehouses stand on surrounding streets.

Gang violence is a serious problem in the area, and the economic crisis has hit many immigrant families hard.

Students and teachers describe the school as a safe haven, a place where, despite a severe lack of resources, teachers offer innovative lessons with real-world context and organize clubs and after-school programs on topics like literature, science, and the environment.

Curie students say they recognize the extra lengths their teachers go to in making sure they get a stimulating, top-flight education even in such trying circumstances. Hence many students and former students have spent the past few days on the picket lines with their teachers and former teachers.

"This is my family," said Nicolas Coronado, 19, a DePaul University political science student on the picket line with his former IB History teacher, Homero Penuelas. "I loved it here."

A student marching band has been helping to keep their teachers' spirits up on the picket line, and one student has even turned up each day in a hot dog costume with a sign saying "Mayor Emanuel Is a Weenie."

On Thursday morning, 2007 Curie graduate Jose Xavier Montenegro gave a younger student pointers on drumming.

"I wasn't the best student but I look up to these teachers," said Montenegro, who now works as a laborer with his own company and competes in power-lifting. "I know what it's like in those classrooms. It's jam-packed; in one class we had 42 students. One time a rat ran through the classroom. Teachers could do a lot more if they had more resources."

Students describe teachers regularly buying supplies out of their own pockets.

"It's like being in a factory and paying your own money for the parts you need to make a phone," said Curie senior Adam Cabanas, 17, standing on the picket line Thursday with senior Cheyenne Watkins. "I love my teachers. They are always there for you."

"They take money out of their own wallets for us," added Watkins, 17. "For teachers to be treated badly after they have put so much of their lives into this is not fair. [The administration] tries to make it look like teachers are hurting students. But students are hurting in the classrooms - there's no air conditioning. You have 38 students in one class."

Jazmin Gonzalez, a seventh-grader at Lindblom Elementary in the nearby Englewood neighborhood, joined her mother and Curie science teacher Maricruz Gonzalez outside the school, wearing a sign around her neck saying "CPS student and daughter of CPS teacher - Double Whammy."

"It's a little scary but this has to happen for teachers to get what they need to teach us effectively, they are some of the hardest working people I've ever met in my life," said Gonzalez about the strike, noting that in her overcrowded classes there are "people sharing desks and sitting at the teacher's desk."

Karina Alcorchas, a 2012 Curie graduate, credits Curie teachers with inspiring her to pursue chemical engineering at the Illinois Institute of Technology. "It's important to give back to the teachers who have given so much to us," said Alcorchas, who earlier in the week walked picket lines with her former elementary school teachers.

Curie highlights the main reasons the teachers union opposes standardized testing used to determine merit-based pay, which the school board has backed off on, and merit-based evaluations, which the board is still demanding. (After negotiations Wednesday, both the school board and union president Karen Lewis said progress was being made and students might be back in class on Friday).

"Merit pay works only in neighborhoods where you're not dealing with the kinds of things we're dealing with here," said Penuelas. "I have students who go to work after school and work until 1 in the morning, then we start school at 7:30 am. Many are the breadwinners in their families. We try our best to help our students but these are hard things to overcome."

Rosana Enriquez, Curie's only social worker, elaborated on the challenges facing students.

"Just last week I talked to three kids whose fathers are in jail, and one whose mother had been deported and she was living with relatives, and teen mothers. That's not to mention the foster kids we serve," she said, noting that more social workers in the schools are desperately needed. "Kids are living with depression and anxiety because of the violence in the neighborhood."

Teachers at Curie, as at many public schools, often incorporate the harsh realities that their students live with into their lesson plans, an approach Penuelas noted can also apply to the strike.

"This is as prime an example as any of a civics lesson," he said. "If parents are worried about their kids being at home not getting an education, they should bring them out here. It's a lesson in democracy and power in numbers."

Marie Sklodowska Curie Metro High School is located in a hardscrabble neighborhood on Chicago's southwest side. A coal-burning power plant lies just to the north and various factories and warehouses stand on surrounding streets.

Gang violence is a serious problem in the area, and the economic crisis has hit many immigrant families hard.

Students and teachers describe the school as a safe haven, a place where, despite a severe lack of resources, teachers offer innovative lessons with real-world context and organize clubs and after-school programs on topics like literature, science, and the environment.

Curie students say they recognize the extra lengths their teachers go to in making sure they get a stimulating, top-flight education even in such trying circumstances. Hence many students and former students have spent the past few days on the picket lines with their teachers and former teachers.

"This is my family," said Nicolas Coronado, 19, a DePaul University political science student on the picket line with his former IB History teacher, Homero Penuelas. "I loved it here."

A student marching band has been helping to keep their teachers' spirits up on the picket line, and one student has even turned up each day in a hot dog costume with a sign saying "Mayor Emanuel Is a Weenie."

On Thursday morning, 2007 Curie graduate Jose Xavier Montenegro gave a younger student pointers on drumming.

"I wasn't the best student but I look up to these teachers," said Montenegro, who now works as a laborer with his own company and competes in power-lifting. "I know what it's like in those classrooms. It's jam-packed; in one class we had 42 students. One time a rat ran through the classroom. Teachers could do a lot more if they had more resources."

Students describe teachers regularly buying supplies out of their own pockets.

"It's like being in a factory and paying your own money for the parts you need to make a phone," said Curie senior Adam Cabanas, 17, standing on the picket line Thursday with senior Cheyenne Watkins. "I love my teachers. They are always there for you."

"They take money out of their own wallets for us," added Watkins, 17. "For teachers to be treated badly after they have put so much of their lives into this is not fair. [The administration] tries to make it look like teachers are hurting students. But students are hurting in the classrooms - there's no air conditioning. You have 38 students in one class."

Jazmin Gonzalez, a seventh-grader at Lindblom Elementary in the nearby Englewood neighborhood, joined her mother and Curie science teacher Maricruz Gonzalez outside the school, wearing a sign around her neck saying "CPS student and daughter of CPS teacher - Double Whammy."

"It's a little scary but this has to happen for teachers to get what they need to teach us effectively, they are some of the hardest working people I've ever met in my life," said Gonzalez about the strike, noting that in her overcrowded classes there are "people sharing desks and sitting at the teacher's desk."

Karina Alcorchas, a 2012 Curie graduate, credits Curie teachers with inspiring her to pursue chemical engineering at the Illinois Institute of Technology. "It's important to give back to the teachers who have given so much to us," said Alcorchas, who earlier in the week walked picket lines with her former elementary school teachers.

Curie highlights the main reasons the teachers union opposes standardized testing used to determine merit-based pay, which the school board has backed off on, and merit-based evaluations, which the board is still demanding. (After negotiations Wednesday, both the school board and union president Karen Lewis said progress was being made and students might be back in class on Friday).

"Merit pay works only in neighborhoods where you're not dealing with the kinds of things we're dealing with here," said Penuelas. "I have students who go to work after school and work until 1 in the morning, then we start school at 7:30 am. Many are the breadwinners in their families. We try our best to help our students but these are hard things to overcome."

Rosana Enriquez, Curie's only social worker, elaborated on the challenges facing students.

"Just last week I talked to three kids whose fathers are in jail, and one whose mother had been deported and she was living with relatives, and teen mothers. That's not to mention the foster kids we serve," she said, noting that more social workers in the schools are desperately needed. "Kids are living with depression and anxiety because of the violence in the neighborhood."

Teachers at Curie, as at many public schools, often incorporate the harsh realities that their students live with into their lesson plans, an approach Penuelas noted can also apply to the strike.

"This is as prime an example as any of a civics lesson," he said. "If parents are worried about their kids being at home not getting an education, they should bring them out here. It's a lesson in democracy and power in numbers."