Oct 03, 2012

The United States does not have presidential debates in any realistic sense of the word.

It holds quadrennial joint appearances by major-party candidates who have been schooled in the art of saying little of consequence in the most absurdly aggressive way. And Americans will be served a full helping this evening, as the travesty that the Commission on Presidential Debates foists on the country every four years begins its latest run.

Much will be said on stage, much more by the punditocracy.

But the likelihood that it will matter is slimmer now than ever. That is because presidential debates have become the political equivalent of a classic rock radio station. You'll hear all the hits, and maybe even a few obscure tracks that you'd almost forgotten. But the whole point of the Barack Obama's appearance will be to say nothing that harms himself and everything that harms Mitt Romney, just as the whole point of Romney's appearance will be to say nothing that harms himself and everything that harms Obama.

Neither man will leave his comfort zone. Neither will jump off the narrow track on which this year's campaign has been running. The only theater will be provided by a gaffe, and in fairness Mitt Romney has proven to be more adept than any figure since Chevy Chase (playing Gerald Ford) in that department.

But America deserves better than drinking games built around the wait for Mitt to be Mitt.

What would make the debates better?

In most developed nation--from Canada to Britain to Australia to France--debates are multi-candidate, multi-party affairs. It is not uncommon for five, six, even seven candidates to take the stage. Those countries do not just survive the clashes, they thrive--with higher levels of political engagement than the United States has seen in decades.

Only the most crudely authoritarian states erect the sort of barriers that the United States maintains to entry into the debates by so-called "minor-party" candidates.

And why?

The fool's argument against expanding the number of contenders is that debates involving more than the nominees of the two big parties--which, conveniently, control the access to the debates through their joint Commission on Presidential Debates--is that it would somehow confuse the electorate. As if Americans aren't quite as sharp as the French.

Adding more candidates would not create confusion. It would add clarity.

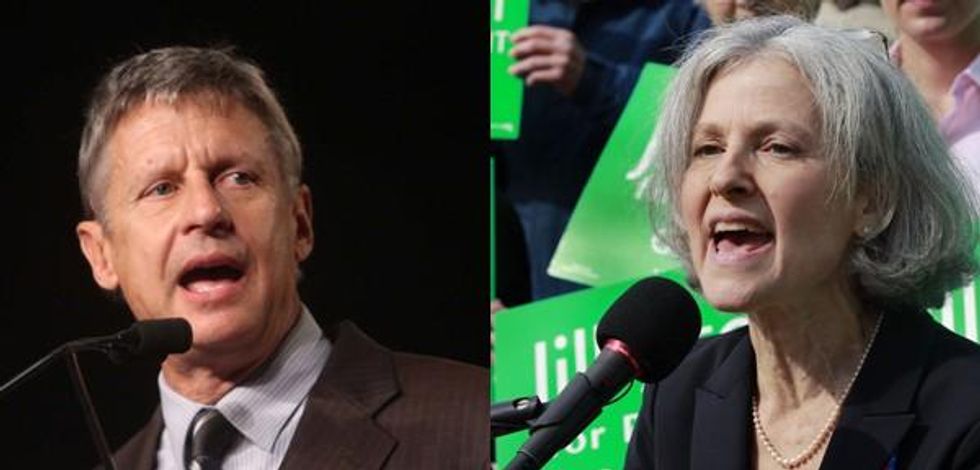

Imagine if Green Party presidential candidate Jill Stein joined Obama and Romney for this year's debates. Instead of having to listen to a pair of adult men trying to distinguish between Obamacare and Romneycare, we could hear a working physician explain why a "Medicare for All" program would be dramatically more efficient, economical and humane than what either the president or his Republican challenger has proposed.

Imagine if Libertarian Gary Johnson could respond to the predictably empty wrangling about whether America is "broke"--as opposed to suffering from broken budget priorities. Johnson would propose bringing American troops and resources home from policing the world's trouble spots, a wholly sensible fix that would make the United States safer, richer and a more popular.

Imagine if Constitution Party candidate Virgil Goode--who once talked about denying a US House seat to Keith Ellison, the first Muslim elected to Congress, because Ellison clutched a Koran rather than a Bible when he was sworn in--opened up a real discussion about the relationship between church and state. Instead of dancing around the issue, as they both do, Obama and Romney would be forced to get specific about how seriously they take the promise of Thomas Jefferson's "wall of separation." They might even call Goode out, sending a message that America needs to hear. from the leaders of both major parties.

By the standards of most countries, Stein, Johnson and Goode could qualify to join national debates. Johnson and Stein have secured places on enough state ballots to win the electoral votes needed to assume the presidency. Goode is already on twenty-six ballots and could yet use legal challenges (and certified write-in campaigns) to be positioned to get on enough additional ballots to win an Electoral College majority. (Other candidates, including former Salt Lake City Mayor Rocky Anderson, whose mounting an intellectually rich and radical run on the Justice Party line, have struggled to get on enough ballots to get near making the Electoral College cut. Anderson will, however, join Stein in a "Debate Talkback" tonight, which will be moderated by Democracy Now!'s Amy Goodman.)

There's not much chance that any of the three will be elected. But at this point, there's not as much chance as there once was that Romney will be elected. It would be absurd to disqualify Romney on the grounds that he's falling behind in the polls, just as it is absurd to disqualify candidates who are on the ballot but have not gotten the exposure that might run their numbers up.

(Notably, Goode is polling well enough in Virginia to be considered a serious threat by the Romney camp, which spent months trying to keep him off that state's ballot. When he finally got on, Goode said: "Candidate Romney, before he continues campaigning, should read the First Amendment about free speech and the right to petition. They're afraid true conservatives will vote for me.")

The value of adding more candidates to the debates is in the quality and diversity of ideas they bring, and in the prospect that they might force the candidates to address--perhaps even embrace--those ideas. This year, in France, Left Front candidate Jean-Luc Melenchon raised the issue of taxing speculators in that country's presidential race. Melenchon only won about 12 percent of the vote, but by the campaign was done both the sitting president, conservative Nicolas Sarkozy, and the man who beat him, Socialist Francois Hollande, were proposing their own variations on the Robin Hood Tax.

Could Stein, Johnson or Goode add as much to the American debate as an experienced campaigner like France's Melenchon? A credible case can be made for each of them. Johnson's a former Republican governor of New Mexico who debated Romney during last year's Republican nomination fight. Goode was a Virginia legislator and member of Congress, serving initially as a Democrat, then as a Republican. Stein, as the Green nominee for governor of Massachusetts in 2002, debated Romney several times, with major media outlets declaring her the winner.

So why not let them in? Oh, right, the rules. But the rules that have been adopted by the Commission on Presidential Debates are based on a deal cut by Democratic and Republican powerbrokers. Either major-party candidate could today call for opening up the debates, and the other would have a hard time keeping them closed.

Unfortunately, neither will opt for openness. Why? Because neither Barack Obama nor Mitt Romney is all that excited about getting dragged into a real debate. And, thanks to the way in which the big parties have rigged the process, neither Obama nor Romney will have to worry about any interesting questions, unexpected issues or pointed challenges interrupting their joint appearance.

Save

On January 20th, it begins...

Political revenge. Mass deportations. Project 2025. Unfathomable corruption. Attacks on Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. Pardons for insurrectionists. An all-out assault on democracy. Republicans in Congress are scrambling to give Trump broad new powers to strip the tax-exempt status of any nonprofit he doesn’t like by declaring it a “terrorist-supporting organization.” Trump has already begun filing lawsuits against news outlets that criticize him. At Common Dreams, we won’t back down, but we must get ready for whatever Trump and his thugs throw at us. Our Year-End campaign is our most important fundraiser of the year. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. By donating today, please help us fight the dangers of a second Trump presidency. |

© 2023 The Nation

John Nichols

John Nichols is Washington correspondent for The Nation and associate editor of The Capital Times in Madison, Wisconsin. His books co-authored with Robert W. McChesney are: "Dollarocracy: How the Money and Media Election Complex is Destroying America" (2014), "The Death and Life of American Journalism: The Media Revolution that Will Begin the World Again" (2011), and "Tragedy & Farce: How the American Media Sell Wars, Spin Elections, and Destroy Democracy" (2006). Nichols' other books include: "The "S" Word: A Short History of an American Tradition...Socialism" (2015), "Dick: The Man Who is President (2004) and "The Genius of Impeachment: The Founders' Cure for Royalism" (2006).

amy goodmanbarack obamaelection 2012francois hollandegreen partyjill steinjohn nicholsjustice partymedicare for allrobin hood taxrocky anderson

The United States does not have presidential debates in any realistic sense of the word.

It holds quadrennial joint appearances by major-party candidates who have been schooled in the art of saying little of consequence in the most absurdly aggressive way. And Americans will be served a full helping this evening, as the travesty that the Commission on Presidential Debates foists on the country every four years begins its latest run.

Much will be said on stage, much more by the punditocracy.

But the likelihood that it will matter is slimmer now than ever. That is because presidential debates have become the political equivalent of a classic rock radio station. You'll hear all the hits, and maybe even a few obscure tracks that you'd almost forgotten. But the whole point of the Barack Obama's appearance will be to say nothing that harms himself and everything that harms Mitt Romney, just as the whole point of Romney's appearance will be to say nothing that harms himself and everything that harms Obama.

Neither man will leave his comfort zone. Neither will jump off the narrow track on which this year's campaign has been running. The only theater will be provided by a gaffe, and in fairness Mitt Romney has proven to be more adept than any figure since Chevy Chase (playing Gerald Ford) in that department.

But America deserves better than drinking games built around the wait for Mitt to be Mitt.

What would make the debates better?

In most developed nation--from Canada to Britain to Australia to France--debates are multi-candidate, multi-party affairs. It is not uncommon for five, six, even seven candidates to take the stage. Those countries do not just survive the clashes, they thrive--with higher levels of political engagement than the United States has seen in decades.

Only the most crudely authoritarian states erect the sort of barriers that the United States maintains to entry into the debates by so-called "minor-party" candidates.

And why?

The fool's argument against expanding the number of contenders is that debates involving more than the nominees of the two big parties--which, conveniently, control the access to the debates through their joint Commission on Presidential Debates--is that it would somehow confuse the electorate. As if Americans aren't quite as sharp as the French.

Adding more candidates would not create confusion. It would add clarity.

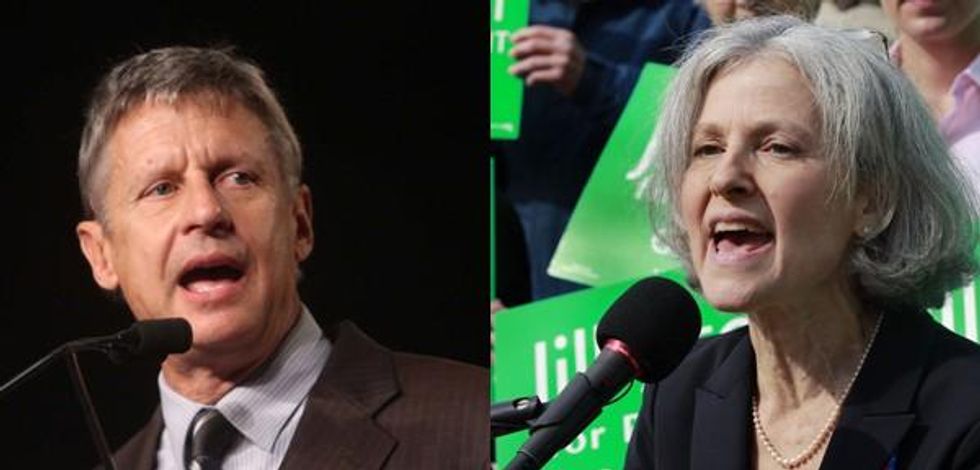

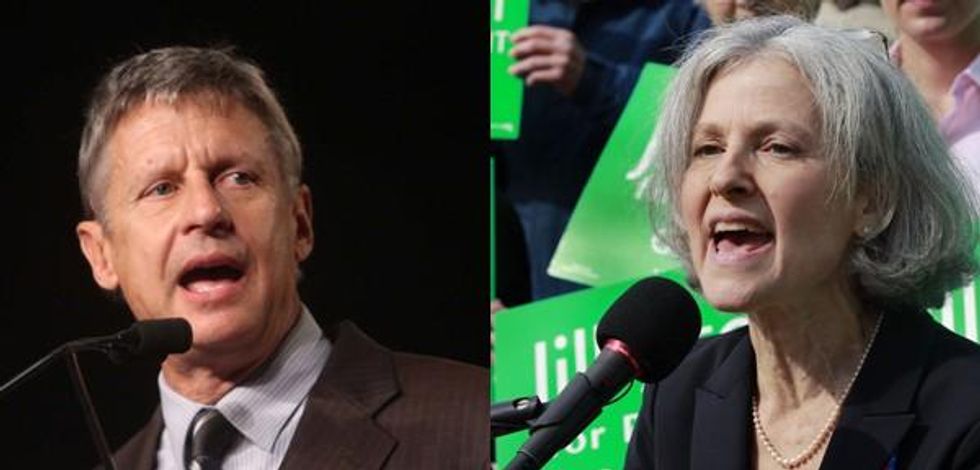

Imagine if Green Party presidential candidate Jill Stein joined Obama and Romney for this year's debates. Instead of having to listen to a pair of adult men trying to distinguish between Obamacare and Romneycare, we could hear a working physician explain why a "Medicare for All" program would be dramatically more efficient, economical and humane than what either the president or his Republican challenger has proposed.

Imagine if Libertarian Gary Johnson could respond to the predictably empty wrangling about whether America is "broke"--as opposed to suffering from broken budget priorities. Johnson would propose bringing American troops and resources home from policing the world's trouble spots, a wholly sensible fix that would make the United States safer, richer and a more popular.

Imagine if Constitution Party candidate Virgil Goode--who once talked about denying a US House seat to Keith Ellison, the first Muslim elected to Congress, because Ellison clutched a Koran rather than a Bible when he was sworn in--opened up a real discussion about the relationship between church and state. Instead of dancing around the issue, as they both do, Obama and Romney would be forced to get specific about how seriously they take the promise of Thomas Jefferson's "wall of separation." They might even call Goode out, sending a message that America needs to hear. from the leaders of both major parties.

By the standards of most countries, Stein, Johnson and Goode could qualify to join national debates. Johnson and Stein have secured places on enough state ballots to win the electoral votes needed to assume the presidency. Goode is already on twenty-six ballots and could yet use legal challenges (and certified write-in campaigns) to be positioned to get on enough additional ballots to win an Electoral College majority. (Other candidates, including former Salt Lake City Mayor Rocky Anderson, whose mounting an intellectually rich and radical run on the Justice Party line, have struggled to get on enough ballots to get near making the Electoral College cut. Anderson will, however, join Stein in a "Debate Talkback" tonight, which will be moderated by Democracy Now!'s Amy Goodman.)

There's not much chance that any of the three will be elected. But at this point, there's not as much chance as there once was that Romney will be elected. It would be absurd to disqualify Romney on the grounds that he's falling behind in the polls, just as it is absurd to disqualify candidates who are on the ballot but have not gotten the exposure that might run their numbers up.

(Notably, Goode is polling well enough in Virginia to be considered a serious threat by the Romney camp, which spent months trying to keep him off that state's ballot. When he finally got on, Goode said: "Candidate Romney, before he continues campaigning, should read the First Amendment about free speech and the right to petition. They're afraid true conservatives will vote for me.")

The value of adding more candidates to the debates is in the quality and diversity of ideas they bring, and in the prospect that they might force the candidates to address--perhaps even embrace--those ideas. This year, in France, Left Front candidate Jean-Luc Melenchon raised the issue of taxing speculators in that country's presidential race. Melenchon only won about 12 percent of the vote, but by the campaign was done both the sitting president, conservative Nicolas Sarkozy, and the man who beat him, Socialist Francois Hollande, were proposing their own variations on the Robin Hood Tax.

Could Stein, Johnson or Goode add as much to the American debate as an experienced campaigner like France's Melenchon? A credible case can be made for each of them. Johnson's a former Republican governor of New Mexico who debated Romney during last year's Republican nomination fight. Goode was a Virginia legislator and member of Congress, serving initially as a Democrat, then as a Republican. Stein, as the Green nominee for governor of Massachusetts in 2002, debated Romney several times, with major media outlets declaring her the winner.

So why not let them in? Oh, right, the rules. But the rules that have been adopted by the Commission on Presidential Debates are based on a deal cut by Democratic and Republican powerbrokers. Either major-party candidate could today call for opening up the debates, and the other would have a hard time keeping them closed.

Unfortunately, neither will opt for openness. Why? Because neither Barack Obama nor Mitt Romney is all that excited about getting dragged into a real debate. And, thanks to the way in which the big parties have rigged the process, neither Obama nor Romney will have to worry about any interesting questions, unexpected issues or pointed challenges interrupting their joint appearance.

Save

John Nichols

John Nichols is Washington correspondent for The Nation and associate editor of The Capital Times in Madison, Wisconsin. His books co-authored with Robert W. McChesney are: "Dollarocracy: How the Money and Media Election Complex is Destroying America" (2014), "The Death and Life of American Journalism: The Media Revolution that Will Begin the World Again" (2011), and "Tragedy & Farce: How the American Media Sell Wars, Spin Elections, and Destroy Democracy" (2006). Nichols' other books include: "The "S" Word: A Short History of an American Tradition...Socialism" (2015), "Dick: The Man Who is President (2004) and "The Genius of Impeachment: The Founders' Cure for Royalism" (2006).

The United States does not have presidential debates in any realistic sense of the word.

It holds quadrennial joint appearances by major-party candidates who have been schooled in the art of saying little of consequence in the most absurdly aggressive way. And Americans will be served a full helping this evening, as the travesty that the Commission on Presidential Debates foists on the country every four years begins its latest run.

Much will be said on stage, much more by the punditocracy.

But the likelihood that it will matter is slimmer now than ever. That is because presidential debates have become the political equivalent of a classic rock radio station. You'll hear all the hits, and maybe even a few obscure tracks that you'd almost forgotten. But the whole point of the Barack Obama's appearance will be to say nothing that harms himself and everything that harms Mitt Romney, just as the whole point of Romney's appearance will be to say nothing that harms himself and everything that harms Obama.

Neither man will leave his comfort zone. Neither will jump off the narrow track on which this year's campaign has been running. The only theater will be provided by a gaffe, and in fairness Mitt Romney has proven to be more adept than any figure since Chevy Chase (playing Gerald Ford) in that department.

But America deserves better than drinking games built around the wait for Mitt to be Mitt.

What would make the debates better?

In most developed nation--from Canada to Britain to Australia to France--debates are multi-candidate, multi-party affairs. It is not uncommon for five, six, even seven candidates to take the stage. Those countries do not just survive the clashes, they thrive--with higher levels of political engagement than the United States has seen in decades.

Only the most crudely authoritarian states erect the sort of barriers that the United States maintains to entry into the debates by so-called "minor-party" candidates.

And why?

The fool's argument against expanding the number of contenders is that debates involving more than the nominees of the two big parties--which, conveniently, control the access to the debates through their joint Commission on Presidential Debates--is that it would somehow confuse the electorate. As if Americans aren't quite as sharp as the French.

Adding more candidates would not create confusion. It would add clarity.

Imagine if Green Party presidential candidate Jill Stein joined Obama and Romney for this year's debates. Instead of having to listen to a pair of adult men trying to distinguish between Obamacare and Romneycare, we could hear a working physician explain why a "Medicare for All" program would be dramatically more efficient, economical and humane than what either the president or his Republican challenger has proposed.

Imagine if Libertarian Gary Johnson could respond to the predictably empty wrangling about whether America is "broke"--as opposed to suffering from broken budget priorities. Johnson would propose bringing American troops and resources home from policing the world's trouble spots, a wholly sensible fix that would make the United States safer, richer and a more popular.

Imagine if Constitution Party candidate Virgil Goode--who once talked about denying a US House seat to Keith Ellison, the first Muslim elected to Congress, because Ellison clutched a Koran rather than a Bible when he was sworn in--opened up a real discussion about the relationship between church and state. Instead of dancing around the issue, as they both do, Obama and Romney would be forced to get specific about how seriously they take the promise of Thomas Jefferson's "wall of separation." They might even call Goode out, sending a message that America needs to hear. from the leaders of both major parties.

By the standards of most countries, Stein, Johnson and Goode could qualify to join national debates. Johnson and Stein have secured places on enough state ballots to win the electoral votes needed to assume the presidency. Goode is already on twenty-six ballots and could yet use legal challenges (and certified write-in campaigns) to be positioned to get on enough additional ballots to win an Electoral College majority. (Other candidates, including former Salt Lake City Mayor Rocky Anderson, whose mounting an intellectually rich and radical run on the Justice Party line, have struggled to get on enough ballots to get near making the Electoral College cut. Anderson will, however, join Stein in a "Debate Talkback" tonight, which will be moderated by Democracy Now!'s Amy Goodman.)

There's not much chance that any of the three will be elected. But at this point, there's not as much chance as there once was that Romney will be elected. It would be absurd to disqualify Romney on the grounds that he's falling behind in the polls, just as it is absurd to disqualify candidates who are on the ballot but have not gotten the exposure that might run their numbers up.

(Notably, Goode is polling well enough in Virginia to be considered a serious threat by the Romney camp, which spent months trying to keep him off that state's ballot. When he finally got on, Goode said: "Candidate Romney, before he continues campaigning, should read the First Amendment about free speech and the right to petition. They're afraid true conservatives will vote for me.")

The value of adding more candidates to the debates is in the quality and diversity of ideas they bring, and in the prospect that they might force the candidates to address--perhaps even embrace--those ideas. This year, in France, Left Front candidate Jean-Luc Melenchon raised the issue of taxing speculators in that country's presidential race. Melenchon only won about 12 percent of the vote, but by the campaign was done both the sitting president, conservative Nicolas Sarkozy, and the man who beat him, Socialist Francois Hollande, were proposing their own variations on the Robin Hood Tax.

Could Stein, Johnson or Goode add as much to the American debate as an experienced campaigner like France's Melenchon? A credible case can be made for each of them. Johnson's a former Republican governor of New Mexico who debated Romney during last year's Republican nomination fight. Goode was a Virginia legislator and member of Congress, serving initially as a Democrat, then as a Republican. Stein, as the Green nominee for governor of Massachusetts in 2002, debated Romney several times, with major media outlets declaring her the winner.

So why not let them in? Oh, right, the rules. But the rules that have been adopted by the Commission on Presidential Debates are based on a deal cut by Democratic and Republican powerbrokers. Either major-party candidate could today call for opening up the debates, and the other would have a hard time keeping them closed.

Unfortunately, neither will opt for openness. Why? Because neither Barack Obama nor Mitt Romney is all that excited about getting dragged into a real debate. And, thanks to the way in which the big parties have rigged the process, neither Obama nor Romney will have to worry about any interesting questions, unexpected issues or pointed challenges interrupting their joint appearance.

Save

We've had enough. The 1% own and operate the corporate media. They are doing everything they can to defend the status quo, squash dissent and protect the wealthy and the powerful. The Common Dreams media model is different. We cover the news that matters to the 99%. Our mission? To inform. To inspire. To ignite change for the common good. How? Nonprofit. Independent. Reader-supported. Free to read. Free to republish. Free to share. With no advertising. No paywalls. No selling of your data. Thousands of small donations fund our newsroom and allow us to continue publishing. Can you chip in? We can't do it without you. Thank you.