The Dirty Little Secret of Private Equity Profits

Today, for the first time, I am officially notifying the honchos of Bain Capital, Blackstone Group, Carlyle Group, Kohlberg Kravis Roberts and other big-time private equity funds that I am available. My little company, Saddle Burr Productions, can be had. For a price.

I publish this notice in response to a recent news item revealing that these firms have a unique and perplexing problem: They have too much money on hand. In all, they're holding a cool trillion dollars that super-rich speculators, banks and others have entrusted to them. Private equity funds are corporate predators that borrow huge sums from these richies, using the cash to buy out targeted corporations, dismantle them and sell off the parts to make a fat profit for the investors and themselves.

However, in these iffy economic times, these flush funds have hesitated to do big takeovers, so they've just been sitting on all that money (which the predators refer to as "dry powder"). The problem is that, under the rules of this high-stakes casino game, the firms have to spend their borrowed money by a set time -- or give it back. And the clock is ticking.

So, using Wall Street's macho lingo, the big players have announced that they're now ready to go "elephant hunting" and are prepared to fire big bucks to bag some companies. To which I say: Fire away at Saddle Burr Productions!

OK, my company is hardly an elephant. But maybe it could be what the equity hucksters refer to as a "hot potato." That's what they call it when one fund grabs a company just to sell it to another fund, which might pass it off to yet another.

This year, equity firms are expected to spend more than $22 billion this year selling hot potatoes to each other -- in part, just to move cash out the door so they don't have to give it back.

This is what passes for good business sense in the truly screwy world of private equity. It's just churning money, producing absolutely nothing -- except, of course, huge fees for the churners. But if that's the game, hey, put me in the mix.

A billion dollars sounds about right.

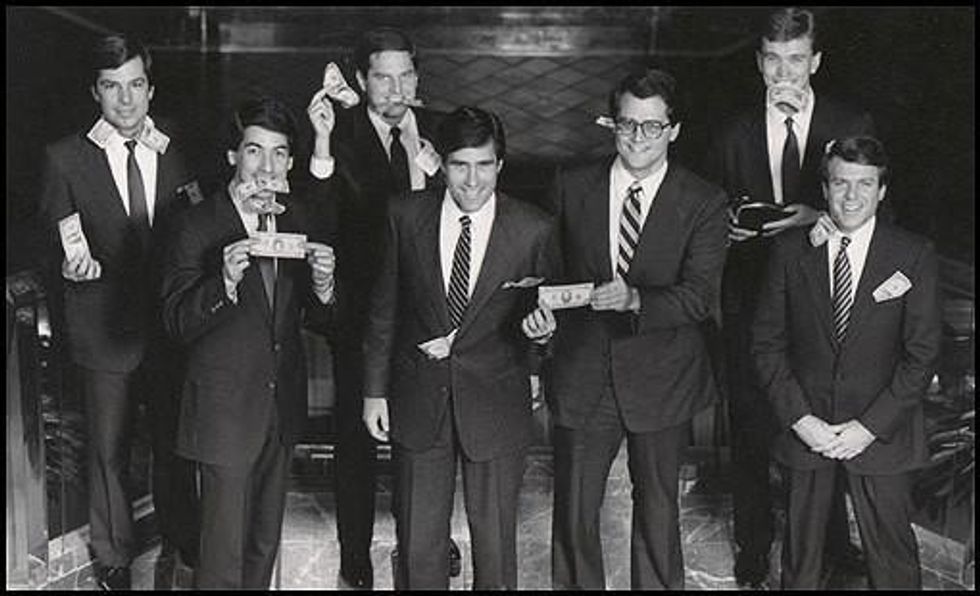

Executives in private equity firms -- such as Mitt Romney of Bain Capital and Henry Kravis of Kohlberg Kravis Roberts -- tend to be peacocks who think quite highly of themselves.

Fanning their splendid tail feathers, they unabashedly claim to be the ultimate free-enterprise risk-takers -- worth every dime of the multimillion-dollar paychecks they award themselves each year. Excuse me, but the risks by these self-anointed "heroes of the market" are actually taken with other people's money, not their own. That's quite a bit short of heroic. But here's a revelation that really ruffles their feathers: It seems they've been hauling in their massive profits not by bold and savvy competition in the marketplace, but through old-fashioned financial collusion with each other.

An antitrust civil lawsuit filed in federal court against 11 of the biggest equity firms includes internal emails in which they agree not to compete. In 2006, for example, yhe head of Blackstone sent an email to the co-founder of KKR: "We would much rather work with you guys than against you. Together we can be unstoppable, but in opposition we can cost each other a lot of money." The KKR honcho happily emailed back a one-word response: "Agreed."

Collusion, of course, perverts the marketplace they pretend to worship, artificially lowering the market price they'd otherwise pay. And they are not shy about playing this mutual backscratching game. In the 2008 takeover of the giant HCA hospital chain, KKR expressly asked its market rivals "to step down on HCA" and not bid. Agreeing to this blatantly illegal collusion, one rival wrote in an email: "All we can do is do unto others as we want them to do unto us. It will pay off in the long run."

For his part, Romney insists that any collusion by Bain occurred after he left the firm. "He had no role," says a spokeswoman. Well, none besides pocketing the loot. Documents from the lawsuit show that Romney clearly received millions in profits from deals that Bain appears to have made through its collusion in the grand game of market manipulation. If so, can we expect him to return those ill-gotten gains?

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Today, for the first time, I am officially notifying the honchos of Bain Capital, Blackstone Group, Carlyle Group, Kohlberg Kravis Roberts and other big-time private equity funds that I am available. My little company, Saddle Burr Productions, can be had. For a price.

I publish this notice in response to a recent news item revealing that these firms have a unique and perplexing problem: They have too much money on hand. In all, they're holding a cool trillion dollars that super-rich speculators, banks and others have entrusted to them. Private equity funds are corporate predators that borrow huge sums from these richies, using the cash to buy out targeted corporations, dismantle them and sell off the parts to make a fat profit for the investors and themselves.

However, in these iffy economic times, these flush funds have hesitated to do big takeovers, so they've just been sitting on all that money (which the predators refer to as "dry powder"). The problem is that, under the rules of this high-stakes casino game, the firms have to spend their borrowed money by a set time -- or give it back. And the clock is ticking.

So, using Wall Street's macho lingo, the big players have announced that they're now ready to go "elephant hunting" and are prepared to fire big bucks to bag some companies. To which I say: Fire away at Saddle Burr Productions!

OK, my company is hardly an elephant. But maybe it could be what the equity hucksters refer to as a "hot potato." That's what they call it when one fund grabs a company just to sell it to another fund, which might pass it off to yet another.

This year, equity firms are expected to spend more than $22 billion this year selling hot potatoes to each other -- in part, just to move cash out the door so they don't have to give it back.

This is what passes for good business sense in the truly screwy world of private equity. It's just churning money, producing absolutely nothing -- except, of course, huge fees for the churners. But if that's the game, hey, put me in the mix.

A billion dollars sounds about right.

Executives in private equity firms -- such as Mitt Romney of Bain Capital and Henry Kravis of Kohlberg Kravis Roberts -- tend to be peacocks who think quite highly of themselves.

Fanning their splendid tail feathers, they unabashedly claim to be the ultimate free-enterprise risk-takers -- worth every dime of the multimillion-dollar paychecks they award themselves each year. Excuse me, but the risks by these self-anointed "heroes of the market" are actually taken with other people's money, not their own. That's quite a bit short of heroic. But here's a revelation that really ruffles their feathers: It seems they've been hauling in their massive profits not by bold and savvy competition in the marketplace, but through old-fashioned financial collusion with each other.

An antitrust civil lawsuit filed in federal court against 11 of the biggest equity firms includes internal emails in which they agree not to compete. In 2006, for example, yhe head of Blackstone sent an email to the co-founder of KKR: "We would much rather work with you guys than against you. Together we can be unstoppable, but in opposition we can cost each other a lot of money." The KKR honcho happily emailed back a one-word response: "Agreed."

Collusion, of course, perverts the marketplace they pretend to worship, artificially lowering the market price they'd otherwise pay. And they are not shy about playing this mutual backscratching game. In the 2008 takeover of the giant HCA hospital chain, KKR expressly asked its market rivals "to step down on HCA" and not bid. Agreeing to this blatantly illegal collusion, one rival wrote in an email: "All we can do is do unto others as we want them to do unto us. It will pay off in the long run."

For his part, Romney insists that any collusion by Bain occurred after he left the firm. "He had no role," says a spokeswoman. Well, none besides pocketing the loot. Documents from the lawsuit show that Romney clearly received millions in profits from deals that Bain appears to have made through its collusion in the grand game of market manipulation. If so, can we expect him to return those ill-gotten gains?

Today, for the first time, I am officially notifying the honchos of Bain Capital, Blackstone Group, Carlyle Group, Kohlberg Kravis Roberts and other big-time private equity funds that I am available. My little company, Saddle Burr Productions, can be had. For a price.

I publish this notice in response to a recent news item revealing that these firms have a unique and perplexing problem: They have too much money on hand. In all, they're holding a cool trillion dollars that super-rich speculators, banks and others have entrusted to them. Private equity funds are corporate predators that borrow huge sums from these richies, using the cash to buy out targeted corporations, dismantle them and sell off the parts to make a fat profit for the investors and themselves.

However, in these iffy economic times, these flush funds have hesitated to do big takeovers, so they've just been sitting on all that money (which the predators refer to as "dry powder"). The problem is that, under the rules of this high-stakes casino game, the firms have to spend their borrowed money by a set time -- or give it back. And the clock is ticking.

So, using Wall Street's macho lingo, the big players have announced that they're now ready to go "elephant hunting" and are prepared to fire big bucks to bag some companies. To which I say: Fire away at Saddle Burr Productions!

OK, my company is hardly an elephant. But maybe it could be what the equity hucksters refer to as a "hot potato." That's what they call it when one fund grabs a company just to sell it to another fund, which might pass it off to yet another.

This year, equity firms are expected to spend more than $22 billion this year selling hot potatoes to each other -- in part, just to move cash out the door so they don't have to give it back.

This is what passes for good business sense in the truly screwy world of private equity. It's just churning money, producing absolutely nothing -- except, of course, huge fees for the churners. But if that's the game, hey, put me in the mix.

A billion dollars sounds about right.

Executives in private equity firms -- such as Mitt Romney of Bain Capital and Henry Kravis of Kohlberg Kravis Roberts -- tend to be peacocks who think quite highly of themselves.

Fanning their splendid tail feathers, they unabashedly claim to be the ultimate free-enterprise risk-takers -- worth every dime of the multimillion-dollar paychecks they award themselves each year. Excuse me, but the risks by these self-anointed "heroes of the market" are actually taken with other people's money, not their own. That's quite a bit short of heroic. But here's a revelation that really ruffles their feathers: It seems they've been hauling in their massive profits not by bold and savvy competition in the marketplace, but through old-fashioned financial collusion with each other.

An antitrust civil lawsuit filed in federal court against 11 of the biggest equity firms includes internal emails in which they agree not to compete. In 2006, for example, yhe head of Blackstone sent an email to the co-founder of KKR: "We would much rather work with you guys than against you. Together we can be unstoppable, but in opposition we can cost each other a lot of money." The KKR honcho happily emailed back a one-word response: "Agreed."

Collusion, of course, perverts the marketplace they pretend to worship, artificially lowering the market price they'd otherwise pay. And they are not shy about playing this mutual backscratching game. In the 2008 takeover of the giant HCA hospital chain, KKR expressly asked its market rivals "to step down on HCA" and not bid. Agreeing to this blatantly illegal collusion, one rival wrote in an email: "All we can do is do unto others as we want them to do unto us. It will pay off in the long run."

For his part, Romney insists that any collusion by Bain occurred after he left the firm. "He had no role," says a spokeswoman. Well, none besides pocketing the loot. Documents from the lawsuit show that Romney clearly received millions in profits from deals that Bain appears to have made through its collusion in the grand game of market manipulation. If so, can we expect him to return those ill-gotten gains?