SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

So many stories of employers pressuring their workers to vote for Romney have come out that you might think workplace intimidation was invented just for this election.

Romney certainly hasn't done much to dispel this perception. In a conference call to the National Federation of Independent Business, the GOP candidate was recorded encouraging business owners to:

"[M]ake it very clear to your employees what you believe is in the best interest of your enterprise and therefore their job and their future in the upcoming elections."

A number of Romney backers took it upon themselves to spell out more clearly to their workers what "the best interest for their job" really means. David Siegel, CEO of Florida's Westgate Resorts, emailed his employees that a second term for Obama would likely give him "no choice but to reduce the size of this company". Republican donor-activists Charles and David Koch were no less subtle when they sent 45,000 employees of their Georgia Pacific paper company a list of whom to vote for, warning that workers "may suffer the consequences" if Obama is re-elected.

Florida-based ASG Software CEO Arthur Allen informed his employees that he was contemplating a merger that would eliminate "60% of the salaries" of the company - should Romney lose. In Ohio, coal mine owner Robert Murray left employees in no doubt that they were expected to attend a Romney rally - off the clock and without pay. In Cuba, at least they pay workers for show demonstrations.

Democrats are apoplectic. But as Romney assured those who have the power to hire and fire thousands of people, there is "nothing illegal about you talking to your employees about what you believe is best for the business". He's right. Heavy-handed? Yes. An abuse of authority? Probably. Against the law? Not likely.

News outlets, on the other hand, are merely confused.

"Can your boss really tell you who to vote for?" asked the Atlantic incredulously, before concluding the answer is "probably yes". Should this be a surprise? Seeing that your boss can legally tell you to do nearly anything else, down to what you may wear, when you may eat and how often you may go to the bathroom (and, if he wishes, demand samples when you do), the question comes across as a little naive. So, too, is the corollary "Can you be fired for expressing political views at work?" Again, the answer is probably yes, which should only be a shock to anyone who has never held a job in an American private-sector workplace.

In truth, as an "at-will" (that is, non-union) employee, you can be fired for much less. In Arizona, you can be fired for using birth control. If you live in any one of 29 states, you can be fired for being gay. You can be fired for being a fan of the Green Bay Packers if your boss roots for the Bears.

Lest you think employer authority ends when you clock out, only four states - California, Colorado, New York and North Dakota - protect workers from being fired for legal activity outside of work. For the rest, workers can and have been fired for anything from smoking to cross-dressing, all in the privacy of their homes. The growing practice of employers demanding job applicants to hand over their Facebook passwords underscores the blurring of the work-life divide in this information age.

But free speech and voting rights are supposed to be more sacrosanct than the integrity of your Facebook account, so one would expect there to be greater political safeguards at work than there actually are. This is not to say they don't exist. Federal law makes it illegal to "intimidate, threaten or coerce" anyone against voting as they wish. But as Siegel, Allen and the Koch brothers have shown, the distinction between possible coercion or intimidation and "worker education" is rather fuzzy in the eyes of the law.

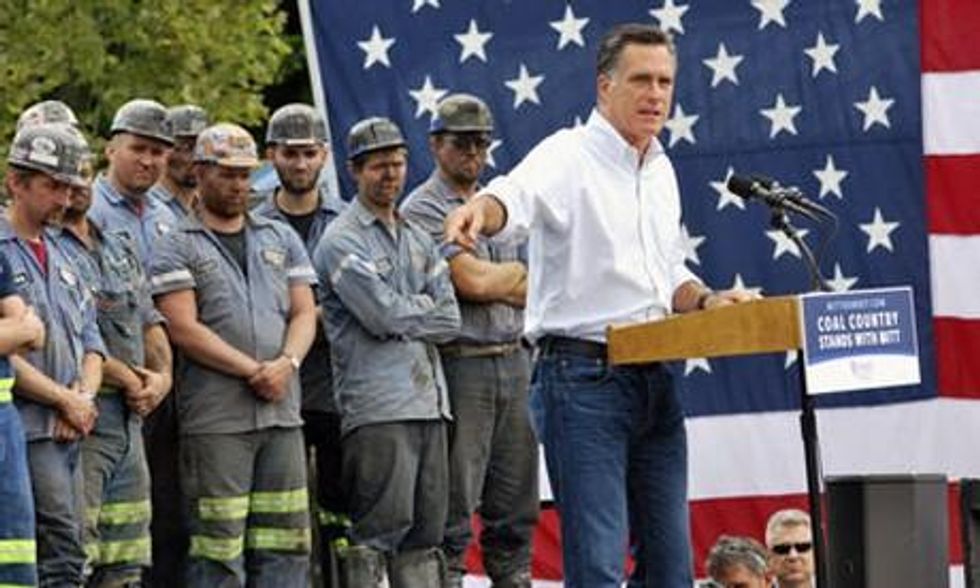

Rather, the federal government largely punted questions of employee free speech to states, a legacy of federalism that hasn't had the best track record when it comes to voting rights. In a state-by-state breakdown, UCLA law professor Eugene Volokh finds such laws vary widely. About half of Americans live in states that provide some worker protection for political speech or from pressure to vote a certain way, such as threat of job loss. Florida is not one of them. Ohio bars employers from forcing workers to sign a petition, but not from standing in front of cameras next to a "Coal Country Stands With Mitt" banner.

Of course, what's on the books is one matter; enforcement is another. Even if you are lucky enough to live in New Mexico and have a signed letter saying you were fired for your Obama tote bag, it typically takes litigation to get your job back. And many people don't have the time or money to go through a court battle, even if the law is on their side.

If anything is happening on the legal end, things are getting worse. The 2010 US supreme court Citizens United case greatly expanded the parameters of what is considered "employer free speech". Most famously, the decision lifted restrictions on corporate campaign spending and gave rise to Super Pacs. But the broader implications are unclear. If Citizens United gives companies free rein to mobilize their resources politically as they wish, one former FEC official suggests that employees could be considered resources which companies may mobilize.

This is why the recent political turn of employee intimidation isn't an anomaly. It's an election year manifestation - aided by the supreme court - of fundamental power imbalances that exist in most workplaces. Brooklyn College political scientist Corey Robin sees a historical pattern:

"During the McCarthy years, the state outsourced the most significant forms of coercion and repression to the workplace. Fewer than 200 people went to jail for their political beliefs, but two out of every five American workers was investigated or subject to surveillance.

"Today, we're seeing a similar process of outsourcing. Government can't tell you how to vote, but it allows CEOs to do so."

Robin concluded:

When workers are forced to go to rallies in communist countries, we call that Stalinism. Here, we call it the free market.

Political revenge. Mass deportations. Project 2025. Unfathomable corruption. Attacks on Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. Pardons for insurrectionists. An all-out assault on democracy. Republicans in Congress are scrambling to give Trump broad new powers to strip the tax-exempt status of any nonprofit he doesn’t like by declaring it a “terrorist-supporting organization.” Trump has already begun filing lawsuits against news outlets that criticize him. At Common Dreams, we won’t back down, but we must get ready for whatever Trump and his thugs throw at us. Our Year-End campaign is our most important fundraiser of the year. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. By donating today, please help us fight the dangers of a second Trump presidency. |

So many stories of employers pressuring their workers to vote for Romney have come out that you might think workplace intimidation was invented just for this election.

Romney certainly hasn't done much to dispel this perception. In a conference call to the National Federation of Independent Business, the GOP candidate was recorded encouraging business owners to:

"[M]ake it very clear to your employees what you believe is in the best interest of your enterprise and therefore their job and their future in the upcoming elections."

A number of Romney backers took it upon themselves to spell out more clearly to their workers what "the best interest for their job" really means. David Siegel, CEO of Florida's Westgate Resorts, emailed his employees that a second term for Obama would likely give him "no choice but to reduce the size of this company". Republican donor-activists Charles and David Koch were no less subtle when they sent 45,000 employees of their Georgia Pacific paper company a list of whom to vote for, warning that workers "may suffer the consequences" if Obama is re-elected.

Florida-based ASG Software CEO Arthur Allen informed his employees that he was contemplating a merger that would eliminate "60% of the salaries" of the company - should Romney lose. In Ohio, coal mine owner Robert Murray left employees in no doubt that they were expected to attend a Romney rally - off the clock and without pay. In Cuba, at least they pay workers for show demonstrations.

Democrats are apoplectic. But as Romney assured those who have the power to hire and fire thousands of people, there is "nothing illegal about you talking to your employees about what you believe is best for the business". He's right. Heavy-handed? Yes. An abuse of authority? Probably. Against the law? Not likely.

News outlets, on the other hand, are merely confused.

"Can your boss really tell you who to vote for?" asked the Atlantic incredulously, before concluding the answer is "probably yes". Should this be a surprise? Seeing that your boss can legally tell you to do nearly anything else, down to what you may wear, when you may eat and how often you may go to the bathroom (and, if he wishes, demand samples when you do), the question comes across as a little naive. So, too, is the corollary "Can you be fired for expressing political views at work?" Again, the answer is probably yes, which should only be a shock to anyone who has never held a job in an American private-sector workplace.

In truth, as an "at-will" (that is, non-union) employee, you can be fired for much less. In Arizona, you can be fired for using birth control. If you live in any one of 29 states, you can be fired for being gay. You can be fired for being a fan of the Green Bay Packers if your boss roots for the Bears.

Lest you think employer authority ends when you clock out, only four states - California, Colorado, New York and North Dakota - protect workers from being fired for legal activity outside of work. For the rest, workers can and have been fired for anything from smoking to cross-dressing, all in the privacy of their homes. The growing practice of employers demanding job applicants to hand over their Facebook passwords underscores the blurring of the work-life divide in this information age.

But free speech and voting rights are supposed to be more sacrosanct than the integrity of your Facebook account, so one would expect there to be greater political safeguards at work than there actually are. This is not to say they don't exist. Federal law makes it illegal to "intimidate, threaten or coerce" anyone against voting as they wish. But as Siegel, Allen and the Koch brothers have shown, the distinction between possible coercion or intimidation and "worker education" is rather fuzzy in the eyes of the law.

Rather, the federal government largely punted questions of employee free speech to states, a legacy of federalism that hasn't had the best track record when it comes to voting rights. In a state-by-state breakdown, UCLA law professor Eugene Volokh finds such laws vary widely. About half of Americans live in states that provide some worker protection for political speech or from pressure to vote a certain way, such as threat of job loss. Florida is not one of them. Ohio bars employers from forcing workers to sign a petition, but not from standing in front of cameras next to a "Coal Country Stands With Mitt" banner.

Of course, what's on the books is one matter; enforcement is another. Even if you are lucky enough to live in New Mexico and have a signed letter saying you were fired for your Obama tote bag, it typically takes litigation to get your job back. And many people don't have the time or money to go through a court battle, even if the law is on their side.

If anything is happening on the legal end, things are getting worse. The 2010 US supreme court Citizens United case greatly expanded the parameters of what is considered "employer free speech". Most famously, the decision lifted restrictions on corporate campaign spending and gave rise to Super Pacs. But the broader implications are unclear. If Citizens United gives companies free rein to mobilize their resources politically as they wish, one former FEC official suggests that employees could be considered resources which companies may mobilize.

This is why the recent political turn of employee intimidation isn't an anomaly. It's an election year manifestation - aided by the supreme court - of fundamental power imbalances that exist in most workplaces. Brooklyn College political scientist Corey Robin sees a historical pattern:

"During the McCarthy years, the state outsourced the most significant forms of coercion and repression to the workplace. Fewer than 200 people went to jail for their political beliefs, but two out of every five American workers was investigated or subject to surveillance.

"Today, we're seeing a similar process of outsourcing. Government can't tell you how to vote, but it allows CEOs to do so."

Robin concluded:

When workers are forced to go to rallies in communist countries, we call that Stalinism. Here, we call it the free market.

So many stories of employers pressuring their workers to vote for Romney have come out that you might think workplace intimidation was invented just for this election.

Romney certainly hasn't done much to dispel this perception. In a conference call to the National Federation of Independent Business, the GOP candidate was recorded encouraging business owners to:

"[M]ake it very clear to your employees what you believe is in the best interest of your enterprise and therefore their job and their future in the upcoming elections."

A number of Romney backers took it upon themselves to spell out more clearly to their workers what "the best interest for their job" really means. David Siegel, CEO of Florida's Westgate Resorts, emailed his employees that a second term for Obama would likely give him "no choice but to reduce the size of this company". Republican donor-activists Charles and David Koch were no less subtle when they sent 45,000 employees of their Georgia Pacific paper company a list of whom to vote for, warning that workers "may suffer the consequences" if Obama is re-elected.

Florida-based ASG Software CEO Arthur Allen informed his employees that he was contemplating a merger that would eliminate "60% of the salaries" of the company - should Romney lose. In Ohio, coal mine owner Robert Murray left employees in no doubt that they were expected to attend a Romney rally - off the clock and without pay. In Cuba, at least they pay workers for show demonstrations.

Democrats are apoplectic. But as Romney assured those who have the power to hire and fire thousands of people, there is "nothing illegal about you talking to your employees about what you believe is best for the business". He's right. Heavy-handed? Yes. An abuse of authority? Probably. Against the law? Not likely.

News outlets, on the other hand, are merely confused.

"Can your boss really tell you who to vote for?" asked the Atlantic incredulously, before concluding the answer is "probably yes". Should this be a surprise? Seeing that your boss can legally tell you to do nearly anything else, down to what you may wear, when you may eat and how often you may go to the bathroom (and, if he wishes, demand samples when you do), the question comes across as a little naive. So, too, is the corollary "Can you be fired for expressing political views at work?" Again, the answer is probably yes, which should only be a shock to anyone who has never held a job in an American private-sector workplace.

In truth, as an "at-will" (that is, non-union) employee, you can be fired for much less. In Arizona, you can be fired for using birth control. If you live in any one of 29 states, you can be fired for being gay. You can be fired for being a fan of the Green Bay Packers if your boss roots for the Bears.

Lest you think employer authority ends when you clock out, only four states - California, Colorado, New York and North Dakota - protect workers from being fired for legal activity outside of work. For the rest, workers can and have been fired for anything from smoking to cross-dressing, all in the privacy of their homes. The growing practice of employers demanding job applicants to hand over their Facebook passwords underscores the blurring of the work-life divide in this information age.

But free speech and voting rights are supposed to be more sacrosanct than the integrity of your Facebook account, so one would expect there to be greater political safeguards at work than there actually are. This is not to say they don't exist. Federal law makes it illegal to "intimidate, threaten or coerce" anyone against voting as they wish. But as Siegel, Allen and the Koch brothers have shown, the distinction between possible coercion or intimidation and "worker education" is rather fuzzy in the eyes of the law.

Rather, the federal government largely punted questions of employee free speech to states, a legacy of federalism that hasn't had the best track record when it comes to voting rights. In a state-by-state breakdown, UCLA law professor Eugene Volokh finds such laws vary widely. About half of Americans live in states that provide some worker protection for political speech or from pressure to vote a certain way, such as threat of job loss. Florida is not one of them. Ohio bars employers from forcing workers to sign a petition, but not from standing in front of cameras next to a "Coal Country Stands With Mitt" banner.

Of course, what's on the books is one matter; enforcement is another. Even if you are lucky enough to live in New Mexico and have a signed letter saying you were fired for your Obama tote bag, it typically takes litigation to get your job back. And many people don't have the time or money to go through a court battle, even if the law is on their side.

If anything is happening on the legal end, things are getting worse. The 2010 US supreme court Citizens United case greatly expanded the parameters of what is considered "employer free speech". Most famously, the decision lifted restrictions on corporate campaign spending and gave rise to Super Pacs. But the broader implications are unclear. If Citizens United gives companies free rein to mobilize their resources politically as they wish, one former FEC official suggests that employees could be considered resources which companies may mobilize.

This is why the recent political turn of employee intimidation isn't an anomaly. It's an election year manifestation - aided by the supreme court - of fundamental power imbalances that exist in most workplaces. Brooklyn College political scientist Corey Robin sees a historical pattern:

"During the McCarthy years, the state outsourced the most significant forms of coercion and repression to the workplace. Fewer than 200 people went to jail for their political beliefs, but two out of every five American workers was investigated or subject to surveillance.

"Today, we're seeing a similar process of outsourcing. Government can't tell you how to vote, but it allows CEOs to do so."

Robin concluded:

When workers are forced to go to rallies in communist countries, we call that Stalinism. Here, we call it the free market.