SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

I suppose it wasn't really until I was standing on the west side of Hoboken, N.J., in water and oil up to my thigh, that climate change really made sense. And it wasn't until I was out organizing on New York City's outer beaches after Hurricane Sandy that I understood my sluggishness on climate justice was nothing short of climate change denial.

I suppose it wasn't really until I was standing on the west side of Hoboken, N.J., in water and oil up to my thigh, that climate change really made sense. And it wasn't until I was out organizing on New York City's outer beaches after Hurricane Sandy that I understood my sluggishness on climate justice was nothing short of climate change denial.

It seems like everywhere we turn, we're being fed the same old climate Armageddon story. You've heard it, I'm sure: If we continue to be dependent on fossil fuels, hundreds of gigatons of CO2 will continue to pour into the atmosphere, the temperature will rise above 2 degrees Celsius, and we're done. There will be a biblical cocktail of hurricanes, floods, famines, wars. It will be terrifying, awful, epic and, yes, as far as any reputable scientist is concerned, those projections are for real.

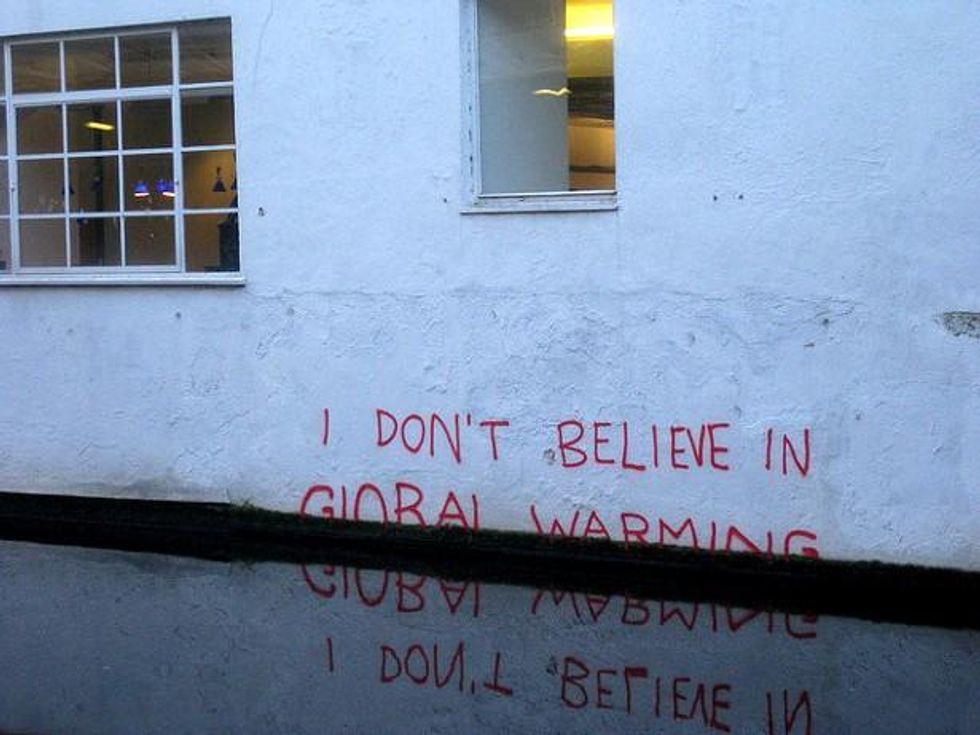

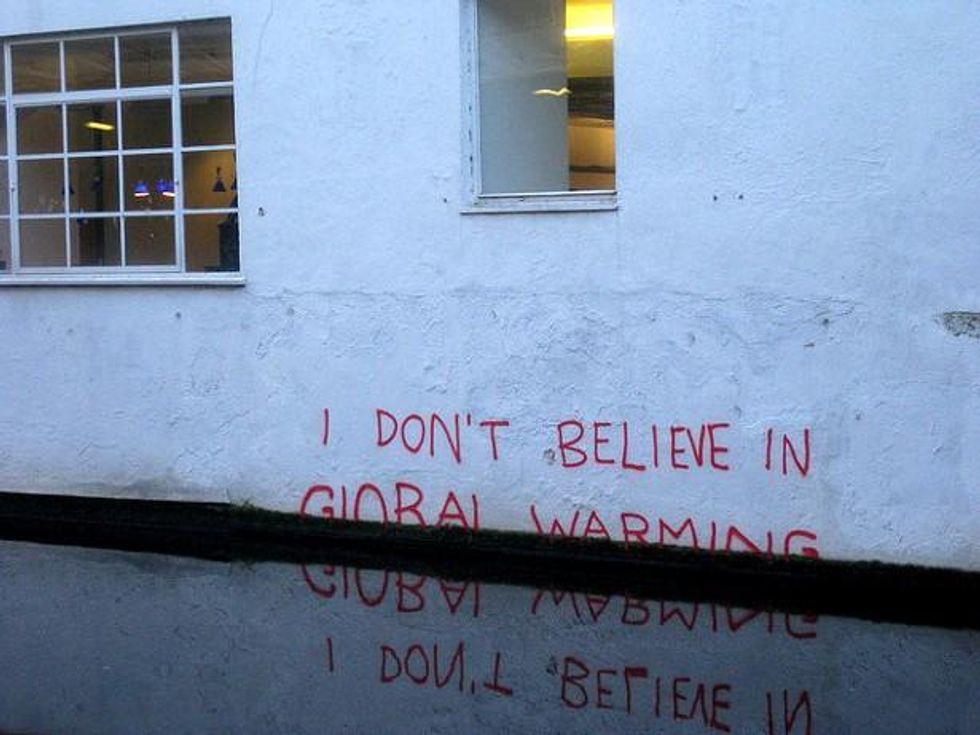

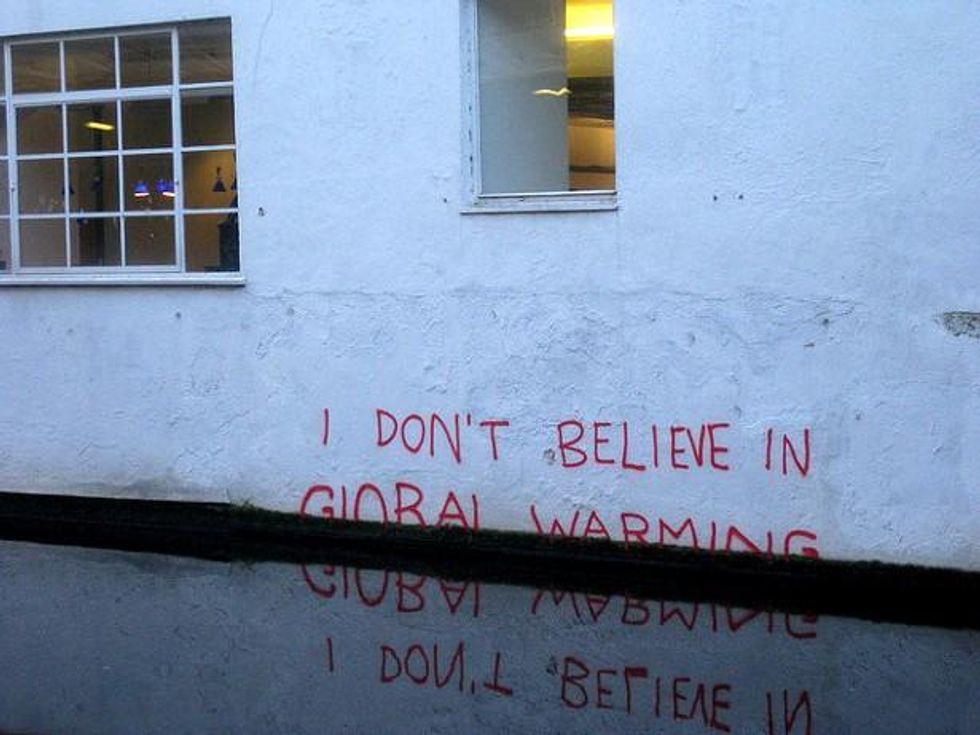

I call this narrative the Armageddon Complex, and my own denial was a product of it. I spun all sorts of stories to keep the climate crisis out of my life, ranging anywhere from "it can't be that bad" to "if it is that bad, there's nothing I can do about it," and "it's not my role. That's for climate activists; I'm a different kind of activist."

I did not act alone, but rather as part of a culture of climate denial among activists, who are already plagued by a tendency to see our work as separate issues vying for attention. The Armageddon Complex tells us that climate activism is about some far-off date, not about the pressing and time-sensitive needs that people around us experience in their day-to-day struggles. It pounds into us the idea that the crisis is more titanic than any other, so if we're going to do anything about it, we have to do everything. Most of us won't put off the pressing needs of our families and communities for something we abstractly understand is going to happen later, and most of us aren't willing to drop the other pieces of our lives and our movement to do everything, because we already feel like we're doing everything and barely scraping by as it is. So we deny.

Unfortunately, there is a lot of truth to this story: The crisis is gargantuan, and it's getting worse. Ultimately only a fundamental social, political, economic and personal transformation is going to get us out of this mess.

But that's not the whole story. Climate Armageddon isn't a Will Smith movie about what happens in 10 years when all hell breaks loose. Climate change is already here: Hurricanes that land on families, rising tides that flood homes, oil spills that drown communities and countless other disasters. These are caused by the same economic and political systems responsible for all the other crises we face -- crises in which people are displaced from land, families are ripped out of homes, people lose their jobs, students sink into debt, and on and on.

Defeating climate change doesn't have to mean dropping everything to become climate activists or ignoring the whole thing altogether. The truth is exactly the opposite: We have to re-learn the climate crisis as one that ties our struggles together and opens up potential for the world we're already busy fighting for.

Climate moment, not climate movement

In addition to the hurricane were important voices that forced me to confront my denial. Naomi Klein has argued that resisting climate change is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to win the world we've wanted all along; the proponents of climate change are the same enemies that the Occupy movement and its counterparts around the world have already marked. Vandana Shiva pushes us to see that the intersecting crises of food, climate and economy are all based on a common theme of debt, while George Monbiot reminds us that the oil profiteering that ruins our climate would be impossible were it not for the insidious relationship between money and politics. These connections mean that the homeowners and activists around the United States putting their bodies on the line to fight foreclosure, the students occupying their universities to fight tuition hikes, the activists fighting for campaign finance reform, the countless who stand up to war -- these struggles are our best shot at a climate movement that can really win.

But I learned those same lessons, too, from people in struggle. Farmers in the Brazilian Landless Workers Movement fighting for their land are not so different from the Lubicon Cree in Northern Alberta, Canada, standing in the way of the Keystone XL pipeline that poisons their water, or the residents in Atlanta, Ga., trying to win their homes back from the banks. The working-class white West Virginians resisting fracking are in the same boat as the families in Far Rockaway whose kids' lungs are infected from living in moldy homes after Hurricane Sandy. They have a lot in common with those in the South Bronx who have been fighting against pollution caused by big business for decades, or the mothers in Detroit who are building urban gardens to cope with food deserts. They're not so different from the Indian women fighting Monsanto, or those resisting wars fought for oil, and on and on the connections go. We're all connected by the climate crisis, and the opportunities it opens for us.

The fight for the climate isn't a separate movement, it's both a challenge and an opportunity for all of our movements. We don't need to become climate activists, we are climate activists. We don't need a separate climate movement; we need to seize the climate moment. Ultimately, our task is to create moments for our various movements that allow us to continue our different battles while also working in solidarity to strike at the roots of the systems beneath the symptoms.

Think Turkey and Brazil. Think Arab Spring, and the uprisings against austerity all over Europe. Think the student movements from Quebec to Chile. Think Occupy. These were collective uprisings that drew lines and demanded that people decide which side they were on. It's our role to prepare for these kinds of "which side are you on?" moments for the climate by training and practicing, by re-focusing on the issues that connect us, by building institutions that can support us in long-term struggle. We don't stop our other organizing or drop the many other pieces of our lives; we organize the people with whom we already stand in order to seize these moments when they come -- to tell stories, take spaces, and challenge enemies of the climate.

Learning from hurricanes

In the New York City neighborhood of Far Rockaway, climate justice is common sense. What I had only read articles and books about before, I learned a thousand times over from people on the front lines of climate crisis after Hurricane Sandy.

As part of Occupy Sandy and the Wildfire Project, I joined the relief effort, which quickly became an organizing project -- training, political education, and supporting the growth of a group that is now active across the Rockaways. Between contesting the city's vision for a recovery, fighting against stop-and-frisk, and organizing against gentrification, the working-class, multiracial Far Rockaway Wildfire group knows that their task is about more than relief from a hurricane -- it is also to deal with the crises that existed before the hurricane, and the systems underlying them.

The fight is about winning back the social safety net that has been slashed by the same economic and political elite that profits from fossil fuels. It's about the wages that have shrunk as elites have profited, about the jobs working people have lost as the bosses have been bailed out. It's about ensuring sustainable mass transit so people can get to work. It's about affordable housing, a need that existed before the storm, made worse now by the threat of disaster capitalist schemes to knock down projects and replace them with beach-front condos. It's about contesting a political system that uses moments of crisis to further disenfranchise working people and people of color. It's about overturning an economic system that is wrecking the planet while turning a profit for the most powerful, putting 40 percent of the wealth of this country into the hands of 1 percent of the population. It's about creating alternatives in our communities, while fighting to make those alternatives the norm.

When you're out on those beaches in Far Rockaway it's clear that there isn't any far-off climate Armageddon to wait for. The hurricanes are already smashing down around us, and they're the same hurricanes as the ones we have fought all along -- systems like capitalism, white supremacy, and patriarchy that shape one another and all the values and institutions that govern our lives. By fighting those systems, we're already the seeds of the climate movement we've been dreaming of. We only need to overcome our denial, find points of intersection in our struggles, and prepare for those moments in which people finally sit down or stand up in the critical intersections of human history. It won't be long now.

This article appears through a collaboration with Transformation, a feature of openDemocracy.net.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

It seems like everywhere we turn, we're being fed the same old climate Armageddon story. You've heard it, I'm sure: If we continue to be dependent on fossil fuels, hundreds of gigatons of CO2 will continue to pour into the atmosphere, the temperature will rise above 2 degrees Celsius, and we're done. There will be a biblical cocktail of hurricanes, floods, famines, wars. It will be terrifying, awful, epic and, yes, as far as any reputable scientist is concerned, those projections are for real.

I call this narrative the Armageddon Complex, and my own denial was a product of it. I spun all sorts of stories to keep the climate crisis out of my life, ranging anywhere from "it can't be that bad" to "if it is that bad, there's nothing I can do about it," and "it's not my role. That's for climate activists; I'm a different kind of activist."

I did not act alone, but rather as part of a culture of climate denial among activists, who are already plagued by a tendency to see our work as separate issues vying for attention. The Armageddon Complex tells us that climate activism is about some far-off date, not about the pressing and time-sensitive needs that people around us experience in their day-to-day struggles. It pounds into us the idea that the crisis is more titanic than any other, so if we're going to do anything about it, we have to do everything. Most of us won't put off the pressing needs of our families and communities for something we abstractly understand is going to happen later, and most of us aren't willing to drop the other pieces of our lives and our movement to do everything, because we already feel like we're doing everything and barely scraping by as it is. So we deny.

Unfortunately, there is a lot of truth to this story: The crisis is gargantuan, and it's getting worse. Ultimately only a fundamental social, political, economic and personal transformation is going to get us out of this mess.

But that's not the whole story. Climate Armageddon isn't a Will Smith movie about what happens in 10 years when all hell breaks loose. Climate change is already here: Hurricanes that land on families, rising tides that flood homes, oil spills that drown communities and countless other disasters. These are caused by the same economic and political systems responsible for all the other crises we face -- crises in which people are displaced from land, families are ripped out of homes, people lose their jobs, students sink into debt, and on and on.

Defeating climate change doesn't have to mean dropping everything to become climate activists or ignoring the whole thing altogether. The truth is exactly the opposite: We have to re-learn the climate crisis as one that ties our struggles together and opens up potential for the world we're already busy fighting for.

Climate moment, not climate movement

In addition to the hurricane were important voices that forced me to confront my denial. Naomi Klein has argued that resisting climate change is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to win the world we've wanted all along; the proponents of climate change are the same enemies that the Occupy movement and its counterparts around the world have already marked. Vandana Shiva pushes us to see that the intersecting crises of food, climate and economy are all based on a common theme of debt, while George Monbiot reminds us that the oil profiteering that ruins our climate would be impossible were it not for the insidious relationship between money and politics. These connections mean that the homeowners and activists around the United States putting their bodies on the line to fight foreclosure, the students occupying their universities to fight tuition hikes, the activists fighting for campaign finance reform, the countless who stand up to war -- these struggles are our best shot at a climate movement that can really win.

But I learned those same lessons, too, from people in struggle. Farmers in the Brazilian Landless Workers Movement fighting for their land are not so different from the Lubicon Cree in Northern Alberta, Canada, standing in the way of the Keystone XL pipeline that poisons their water, or the residents in Atlanta, Ga., trying to win their homes back from the banks. The working-class white West Virginians resisting fracking are in the same boat as the families in Far Rockaway whose kids' lungs are infected from living in moldy homes after Hurricane Sandy. They have a lot in common with those in the South Bronx who have been fighting against pollution caused by big business for decades, or the mothers in Detroit who are building urban gardens to cope with food deserts. They're not so different from the Indian women fighting Monsanto, or those resisting wars fought for oil, and on and on the connections go. We're all connected by the climate crisis, and the opportunities it opens for us.

The fight for the climate isn't a separate movement, it's both a challenge and an opportunity for all of our movements. We don't need to become climate activists, we are climate activists. We don't need a separate climate movement; we need to seize the climate moment. Ultimately, our task is to create moments for our various movements that allow us to continue our different battles while also working in solidarity to strike at the roots of the systems beneath the symptoms.

Think Turkey and Brazil. Think Arab Spring, and the uprisings against austerity all over Europe. Think the student movements from Quebec to Chile. Think Occupy. These were collective uprisings that drew lines and demanded that people decide which side they were on. It's our role to prepare for these kinds of "which side are you on?" moments for the climate by training and practicing, by re-focusing on the issues that connect us, by building institutions that can support us in long-term struggle. We don't stop our other organizing or drop the many other pieces of our lives; we organize the people with whom we already stand in order to seize these moments when they come -- to tell stories, take spaces, and challenge enemies of the climate.

Learning from hurricanes

In the New York City neighborhood of Far Rockaway, climate justice is common sense. What I had only read articles and books about before, I learned a thousand times over from people on the front lines of climate crisis after Hurricane Sandy.

As part of Occupy Sandy and the Wildfire Project, I joined the relief effort, which quickly became an organizing project -- training, political education, and supporting the growth of a group that is now active across the Rockaways. Between contesting the city's vision for a recovery, fighting against stop-and-frisk, and organizing against gentrification, the working-class, multiracial Far Rockaway Wildfire group knows that their task is about more than relief from a hurricane -- it is also to deal with the crises that existed before the hurricane, and the systems underlying them.

The fight is about winning back the social safety net that has been slashed by the same economic and political elite that profits from fossil fuels. It's about the wages that have shrunk as elites have profited, about the jobs working people have lost as the bosses have been bailed out. It's about ensuring sustainable mass transit so people can get to work. It's about affordable housing, a need that existed before the storm, made worse now by the threat of disaster capitalist schemes to knock down projects and replace them with beach-front condos. It's about contesting a political system that uses moments of crisis to further disenfranchise working people and people of color. It's about overturning an economic system that is wrecking the planet while turning a profit for the most powerful, putting 40 percent of the wealth of this country into the hands of 1 percent of the population. It's about creating alternatives in our communities, while fighting to make those alternatives the norm.

When you're out on those beaches in Far Rockaway it's clear that there isn't any far-off climate Armageddon to wait for. The hurricanes are already smashing down around us, and they're the same hurricanes as the ones we have fought all along -- systems like capitalism, white supremacy, and patriarchy that shape one another and all the values and institutions that govern our lives. By fighting those systems, we're already the seeds of the climate movement we've been dreaming of. We only need to overcome our denial, find points of intersection in our struggles, and prepare for those moments in which people finally sit down or stand up in the critical intersections of human history. It won't be long now.

This article appears through a collaboration with Transformation, a feature of openDemocracy.net.

It seems like everywhere we turn, we're being fed the same old climate Armageddon story. You've heard it, I'm sure: If we continue to be dependent on fossil fuels, hundreds of gigatons of CO2 will continue to pour into the atmosphere, the temperature will rise above 2 degrees Celsius, and we're done. There will be a biblical cocktail of hurricanes, floods, famines, wars. It will be terrifying, awful, epic and, yes, as far as any reputable scientist is concerned, those projections are for real.

I call this narrative the Armageddon Complex, and my own denial was a product of it. I spun all sorts of stories to keep the climate crisis out of my life, ranging anywhere from "it can't be that bad" to "if it is that bad, there's nothing I can do about it," and "it's not my role. That's for climate activists; I'm a different kind of activist."

I did not act alone, but rather as part of a culture of climate denial among activists, who are already plagued by a tendency to see our work as separate issues vying for attention. The Armageddon Complex tells us that climate activism is about some far-off date, not about the pressing and time-sensitive needs that people around us experience in their day-to-day struggles. It pounds into us the idea that the crisis is more titanic than any other, so if we're going to do anything about it, we have to do everything. Most of us won't put off the pressing needs of our families and communities for something we abstractly understand is going to happen later, and most of us aren't willing to drop the other pieces of our lives and our movement to do everything, because we already feel like we're doing everything and barely scraping by as it is. So we deny.

Unfortunately, there is a lot of truth to this story: The crisis is gargantuan, and it's getting worse. Ultimately only a fundamental social, political, economic and personal transformation is going to get us out of this mess.

But that's not the whole story. Climate Armageddon isn't a Will Smith movie about what happens in 10 years when all hell breaks loose. Climate change is already here: Hurricanes that land on families, rising tides that flood homes, oil spills that drown communities and countless other disasters. These are caused by the same economic and political systems responsible for all the other crises we face -- crises in which people are displaced from land, families are ripped out of homes, people lose their jobs, students sink into debt, and on and on.

Defeating climate change doesn't have to mean dropping everything to become climate activists or ignoring the whole thing altogether. The truth is exactly the opposite: We have to re-learn the climate crisis as one that ties our struggles together and opens up potential for the world we're already busy fighting for.

Climate moment, not climate movement

In addition to the hurricane were important voices that forced me to confront my denial. Naomi Klein has argued that resisting climate change is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to win the world we've wanted all along; the proponents of climate change are the same enemies that the Occupy movement and its counterparts around the world have already marked. Vandana Shiva pushes us to see that the intersecting crises of food, climate and economy are all based on a common theme of debt, while George Monbiot reminds us that the oil profiteering that ruins our climate would be impossible were it not for the insidious relationship between money and politics. These connections mean that the homeowners and activists around the United States putting their bodies on the line to fight foreclosure, the students occupying their universities to fight tuition hikes, the activists fighting for campaign finance reform, the countless who stand up to war -- these struggles are our best shot at a climate movement that can really win.

But I learned those same lessons, too, from people in struggle. Farmers in the Brazilian Landless Workers Movement fighting for their land are not so different from the Lubicon Cree in Northern Alberta, Canada, standing in the way of the Keystone XL pipeline that poisons their water, or the residents in Atlanta, Ga., trying to win their homes back from the banks. The working-class white West Virginians resisting fracking are in the same boat as the families in Far Rockaway whose kids' lungs are infected from living in moldy homes after Hurricane Sandy. They have a lot in common with those in the South Bronx who have been fighting against pollution caused by big business for decades, or the mothers in Detroit who are building urban gardens to cope with food deserts. They're not so different from the Indian women fighting Monsanto, or those resisting wars fought for oil, and on and on the connections go. We're all connected by the climate crisis, and the opportunities it opens for us.

The fight for the climate isn't a separate movement, it's both a challenge and an opportunity for all of our movements. We don't need to become climate activists, we are climate activists. We don't need a separate climate movement; we need to seize the climate moment. Ultimately, our task is to create moments for our various movements that allow us to continue our different battles while also working in solidarity to strike at the roots of the systems beneath the symptoms.

Think Turkey and Brazil. Think Arab Spring, and the uprisings against austerity all over Europe. Think the student movements from Quebec to Chile. Think Occupy. These were collective uprisings that drew lines and demanded that people decide which side they were on. It's our role to prepare for these kinds of "which side are you on?" moments for the climate by training and practicing, by re-focusing on the issues that connect us, by building institutions that can support us in long-term struggle. We don't stop our other organizing or drop the many other pieces of our lives; we organize the people with whom we already stand in order to seize these moments when they come -- to tell stories, take spaces, and challenge enemies of the climate.

Learning from hurricanes

In the New York City neighborhood of Far Rockaway, climate justice is common sense. What I had only read articles and books about before, I learned a thousand times over from people on the front lines of climate crisis after Hurricane Sandy.

As part of Occupy Sandy and the Wildfire Project, I joined the relief effort, which quickly became an organizing project -- training, political education, and supporting the growth of a group that is now active across the Rockaways. Between contesting the city's vision for a recovery, fighting against stop-and-frisk, and organizing against gentrification, the working-class, multiracial Far Rockaway Wildfire group knows that their task is about more than relief from a hurricane -- it is also to deal with the crises that existed before the hurricane, and the systems underlying them.

The fight is about winning back the social safety net that has been slashed by the same economic and political elite that profits from fossil fuels. It's about the wages that have shrunk as elites have profited, about the jobs working people have lost as the bosses have been bailed out. It's about ensuring sustainable mass transit so people can get to work. It's about affordable housing, a need that existed before the storm, made worse now by the threat of disaster capitalist schemes to knock down projects and replace them with beach-front condos. It's about contesting a political system that uses moments of crisis to further disenfranchise working people and people of color. It's about overturning an economic system that is wrecking the planet while turning a profit for the most powerful, putting 40 percent of the wealth of this country into the hands of 1 percent of the population. It's about creating alternatives in our communities, while fighting to make those alternatives the norm.

When you're out on those beaches in Far Rockaway it's clear that there isn't any far-off climate Armageddon to wait for. The hurricanes are already smashing down around us, and they're the same hurricanes as the ones we have fought all along -- systems like capitalism, white supremacy, and patriarchy that shape one another and all the values and institutions that govern our lives. By fighting those systems, we're already the seeds of the climate movement we've been dreaming of. We only need to overcome our denial, find points of intersection in our struggles, and prepare for those moments in which people finally sit down or stand up in the critical intersections of human history. It won't be long now.

This article appears through a collaboration with Transformation, a feature of openDemocracy.net.