SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

The anniversary of Dr. King's March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom is coming up.

The anniversary of Dr. King's March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom is coming up.

A lot of us will go to Washington again to mark that occasion, and we'll march for jobs again, as well we should, given the current climate. But can I admit something?

I wish we were marching for less work, not more of it.

A lot of us will go to Washington again to mark that occasion, and we'll march for jobs again, as well we should, given the current climate. But can I admit something?

I wish we were marching for less work, not more of it.

I know, it's cheeky to talk about time off. Unemployment is high and jobs are scarce. Americans are supposed to feel grateful to have paid work at all. A vacation too? We're so busy tightening our belts and "leaning in" that even when we do get vacation days at work, we often skip them. Admit it - did you feel guilty taking every last day this summer, or (more likely) guilty that you didn't?

A study by a workforce consulting firm in 2011 reported that 70 percent of employees said they were leaving vacation days on the table. The vast majority of workers, meanwhile, would love some time off, but ours is the last rich country in the world where offering paid time off to workers is optional.

Americans work almost five weeks more a year than our contemporaries in Europe . Family leave is still unpaid under federal law, and the big bosses' lobbies are working like mad to scuttle paid sick days legislation coming out of states and cities.

So we'll march. We'll march for jobs but where do you line up for the march for leisure?

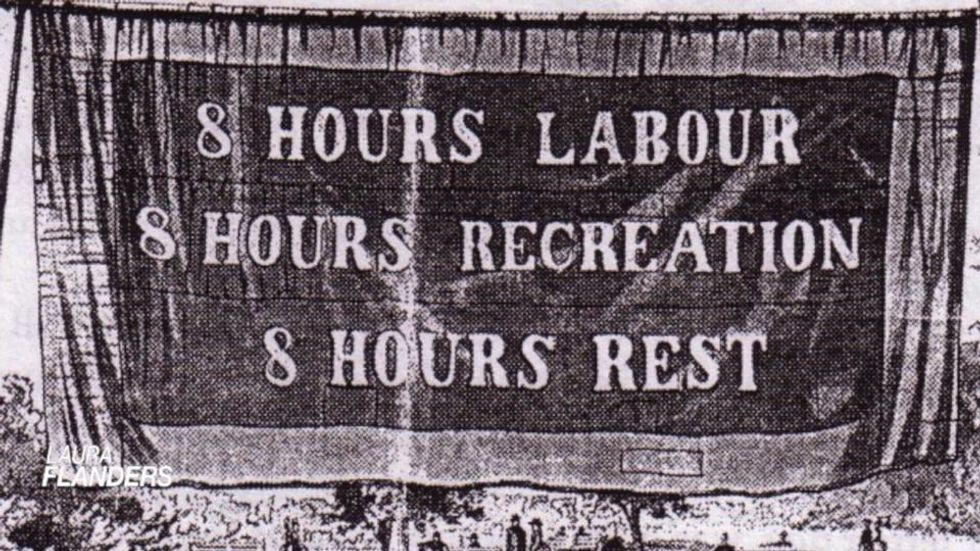

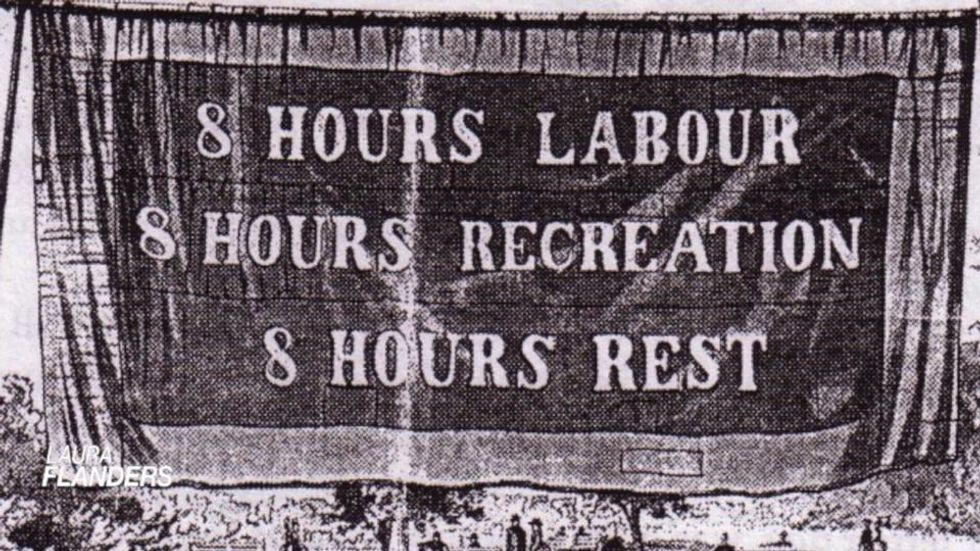

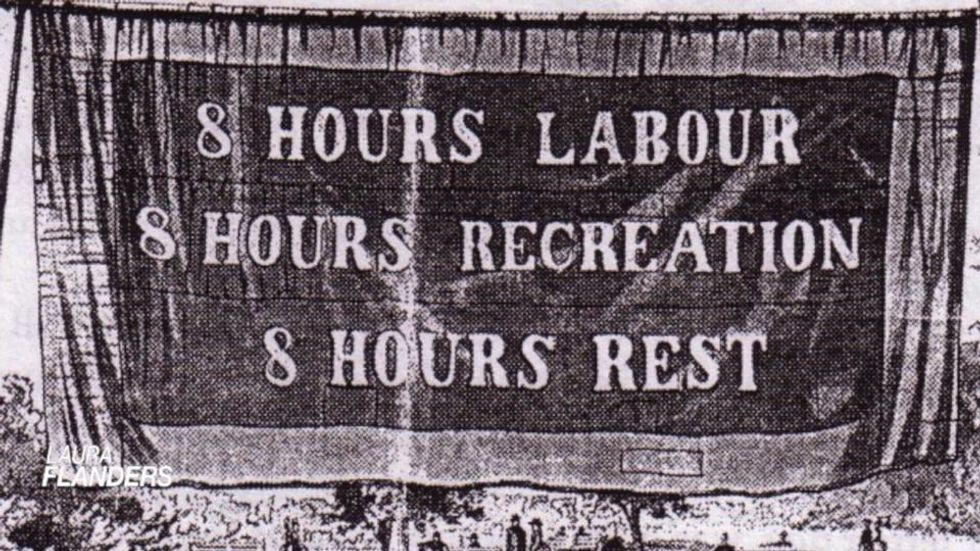

The last time US labor unions marched for that, it was for the eight-hour day, after the depression of 1884. Their banners called for eight hours work and eight hours rest and eight hours for what we will.

The "what we will" part seems to have fallen off the map in the 1930s - and we've had no reductions in work hours since, Duke Professor Kathi Weeks told GRITtv in an interview this week.

The American labor force is the smallest it's been in 20 years and that's not changing. Globalization and computerization are shrinking the demand for US labor. Job sharing and a shorter work-week make sense economically and socially.

Even by raising the topic Kathi Weeks hopes that we might begin to think more critically and imaginatively about, "the possibilities about a life that's not so relentlessly subordinated to work."

If we weren't working so hard, what would we do? If weren't willing to concede to every outrageous demand that we work longer and harder, what would we demand, then?

You can find my conversation with Weeks, the author of The Problem with Work, at GRITtv.org.

Political revenge. Mass deportations. Project 2025. Unfathomable corruption. Attacks on Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. Pardons for insurrectionists. An all-out assault on democracy. Republicans in Congress are scrambling to give Trump broad new powers to strip the tax-exempt status of any nonprofit he doesn’t like by declaring it a “terrorist-supporting organization.” Trump has already begun filing lawsuits against news outlets that criticize him. At Common Dreams, we won’t back down, but we must get ready for whatever Trump and his thugs throw at us. Our Year-End campaign is our most important fundraiser of the year. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. By donating today, please help us fight the dangers of a second Trump presidency. |

A lot of us will go to Washington again to mark that occasion, and we'll march for jobs again, as well we should, given the current climate. But can I admit something?

I wish we were marching for less work, not more of it.

I know, it's cheeky to talk about time off. Unemployment is high and jobs are scarce. Americans are supposed to feel grateful to have paid work at all. A vacation too? We're so busy tightening our belts and "leaning in" that even when we do get vacation days at work, we often skip them. Admit it - did you feel guilty taking every last day this summer, or (more likely) guilty that you didn't?

A study by a workforce consulting firm in 2011 reported that 70 percent of employees said they were leaving vacation days on the table. The vast majority of workers, meanwhile, would love some time off, but ours is the last rich country in the world where offering paid time off to workers is optional.

Americans work almost five weeks more a year than our contemporaries in Europe . Family leave is still unpaid under federal law, and the big bosses' lobbies are working like mad to scuttle paid sick days legislation coming out of states and cities.

So we'll march. We'll march for jobs but where do you line up for the march for leisure?

The last time US labor unions marched for that, it was for the eight-hour day, after the depression of 1884. Their banners called for eight hours work and eight hours rest and eight hours for what we will.

The "what we will" part seems to have fallen off the map in the 1930s - and we've had no reductions in work hours since, Duke Professor Kathi Weeks told GRITtv in an interview this week.

The American labor force is the smallest it's been in 20 years and that's not changing. Globalization and computerization are shrinking the demand for US labor. Job sharing and a shorter work-week make sense economically and socially.

Even by raising the topic Kathi Weeks hopes that we might begin to think more critically and imaginatively about, "the possibilities about a life that's not so relentlessly subordinated to work."

If we weren't working so hard, what would we do? If weren't willing to concede to every outrageous demand that we work longer and harder, what would we demand, then?

You can find my conversation with Weeks, the author of The Problem with Work, at GRITtv.org.

A lot of us will go to Washington again to mark that occasion, and we'll march for jobs again, as well we should, given the current climate. But can I admit something?

I wish we were marching for less work, not more of it.

I know, it's cheeky to talk about time off. Unemployment is high and jobs are scarce. Americans are supposed to feel grateful to have paid work at all. A vacation too? We're so busy tightening our belts and "leaning in" that even when we do get vacation days at work, we often skip them. Admit it - did you feel guilty taking every last day this summer, or (more likely) guilty that you didn't?

A study by a workforce consulting firm in 2011 reported that 70 percent of employees said they were leaving vacation days on the table. The vast majority of workers, meanwhile, would love some time off, but ours is the last rich country in the world where offering paid time off to workers is optional.

Americans work almost five weeks more a year than our contemporaries in Europe . Family leave is still unpaid under federal law, and the big bosses' lobbies are working like mad to scuttle paid sick days legislation coming out of states and cities.

So we'll march. We'll march for jobs but where do you line up for the march for leisure?

The last time US labor unions marched for that, it was for the eight-hour day, after the depression of 1884. Their banners called for eight hours work and eight hours rest and eight hours for what we will.

The "what we will" part seems to have fallen off the map in the 1930s - and we've had no reductions in work hours since, Duke Professor Kathi Weeks told GRITtv in an interview this week.

The American labor force is the smallest it's been in 20 years and that's not changing. Globalization and computerization are shrinking the demand for US labor. Job sharing and a shorter work-week make sense economically and socially.

Even by raising the topic Kathi Weeks hopes that we might begin to think more critically and imaginatively about, "the possibilities about a life that's not so relentlessly subordinated to work."

If we weren't working so hard, what would we do? If weren't willing to concede to every outrageous demand that we work longer and harder, what would we demand, then?

You can find my conversation with Weeks, the author of The Problem with Work, at GRITtv.org.