The riveting attention paid to chemical weapons in Syria over the past few weeks is not a new phenomenon. Our revulsion has its roots in World War I's searing plumes of mustard gas that decimated thousands of troops and that still swirl through the trenches of our collective mind. But it is also grounded in our conscious or unconscious memory of every pivotal moment in the history of war when one combatant's edge widened incrementally or dramatically over another with the latest innovation in killing.

The ability of new weaponry to mechanize and geometrically multiply casualties with every turn of the technological wheel has proven chillingly advantageous to systems of domination. But this superiority has not only been numerical. Its power often has laid in its capability to deface and ultimately obliterate the facticity and stubbornly human presence of the other -- whether it be with the meat grinding Gatling gun of the Civil War or the vaporous immensity of the atomic bomb. Virtually every new weapon over the past 5,000 years has not only been designed to defeat the opponent with greater firepower but to reduce, ruin and extinguish her or his body, presence, physical integrity -- the qualities that makes us irreducibly human.

We are now in the midst of the drones revolution, the next leap in technologized lethality. The quantitative horror that drones have ushered into the world is deeply troubling. For example, U.S. drones have killed an estimated 3,149 people in Pakistan since 2004, as Out of Sight, Out of Mind vividly documents. At the same time a qualitative horror rumbles through our collective consciousness rooted in the growing capacities of drones, including their radical particularity, universal comprehensiveness, and increasing automation.

The precision of drones has dramatically refashioned the concept of most battlefield weapons, which steadily have increased the ability to kill large numbers of people. A military drone, on the contrary, is hyper-personal, designed and tailored to kill a particular person. While the United States regularly carries out what it terms signature strikes -- aimed at classes of people that are presumed to be terrorists because they match a certain demographic profile (young men, for example) -- the stark reality of drones is that they are designed to track and eliminate specific individuals.

Paradoxically, this very particularity makes the potential reach of drones universal. One by one, we are all hypothetically at risk. Any one of us could find ourselves on a "kill list" if we are deemed by "deemers" to fit the system's criteria at any given moment. As the NSA revelations of Edward Snowden and others have underscored, the capacity increasingly exists for the U.S. government and other entities to amass profiles on every human being on the planet. Perhaps all seven billion of us are on a master list whereby the "deemer-in-chief" can toggle us from the "non-kill list" to the "kill list" when national security demands it. Whether this is the case or not, the growing capacity of drones to roam the planet to track and eliminate targets drawn from a comprehensive super-database is a prospect with which we must grapple going forward.

Even more than this, there is the possibility that such a comprehensive system will become virtually automated. Not only might there be a universal list, it could be activated and maintained by a set of algorithms, freeing those glued to the monitors and working the joysticks at places like Creech Air Force Base in Nevada -- as well as their bosses who now compile and sign off on the lists -- from the sometimes PTSD-inducing task of deciding who will live and who will die.

All these facets of drones -- customizable killing, planet-wide surveillance and targeting, and the potential for them to be the lynchpin of a self-regulating, ubiquitous and permanent military regime -- increase lethality but also degrade, destroy and erase the inviolable human presence.

The drones revolution is on, and every effort is being made to get us to enlist. Over the past few years this has included an unrelenting touting that drones are a foregone conclusion. Virtually every day there are new revelations in the press -- for example, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency recently announced that it was working on underwater drones, and there seems to be a thriving "do-it-yourself" drones cottage industry -- while U.S. drone warfare continues apace in the Middle East and the Horn of Africa. (Although most analysts downplay the role drones might play in Syria if the United States goes in, this spring a news account detailed how the CIA has plans to carry out drone attacks against extremists in the Syrian opposition.) This is a new form of subtle and not-so-subtle conscription, designed not so much to fill the ranks of the armed services as to gradually get us to assume that a drone-run world is normal, good and just another part of the future.

But there is resistance to this "cultural draft," including the international movement that, for the past few years, has been growing and broadening. (In reflecting on this movement, I recently explored the idea of promulgating an international treaty banning drones, inspired by the international treaty banning land mines.) Code Pink, which has provided powerful leadership for this movement, is sponsoring a drones summit November 16-17 in Washington, D.C. "Drones Around the Globe: Proliferation and Resistance" will feature among other presenters Cornel West, international law expert Mary Ellen O'Connell, and activists from Yemen and Pakistan.

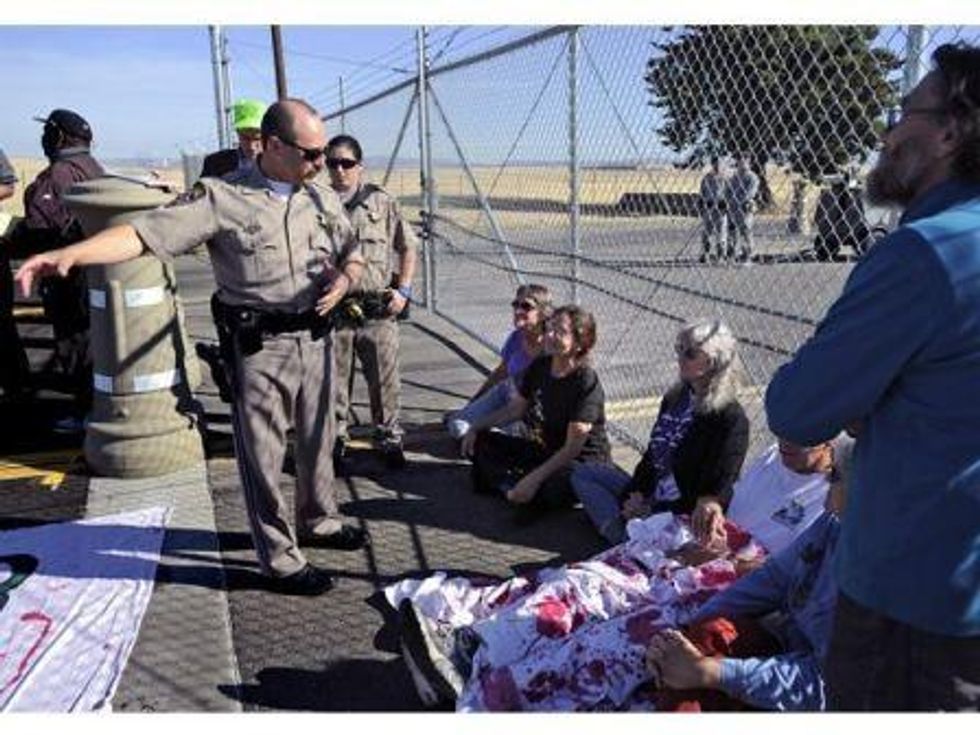

Anti-drone protests have been staged recently in Yemen and Britain. And this week, the "Beale 5" were sentenced in a Sacramento, Calif., courtroom for a nonviolent civil disobedience action they engaged in October 30, 2012 at Beale Air Force Base in Northern California, which provides surveillance drones that scout locations for killer drones. Last month they were convicted of trespassing at the base after a day-long bench trial, where they faced a maximum sentence of six months in federal prison and a $5,000 fine. Judge Carolyn Delaney sentenced the five -- Janie Kesselman, Sharon Delgado, Shirley Osgood, Jan Hartsough and David Hartsough -- to 10 hours of community service after the defendants told her that they would rather go to jail rather than accept fines or probation.

In her statement before the judge, Jan Hartsough, who was a Peace Corps volunteer in Pakistan in the mid-1960s, said:

After living and working there for two years, Pakistan is a part of me. I have followed with great pain and sadness the drone attacks on Pakistanis. I have learned from Pakistani victims of drone strikes that they are experiencing psychological trauma -- never knowing when a drone might strike again. Kids are afraid to go to school; adults are afraid to gather for a funeral or a wedding celebration for fear of becoming a "target." ... So what have we accomplished with our drone attacks? When will we wake up and see that there are much better ways to win the respect of the world's people? As a mother and grandmother I seek to find ways to help create a more peaceful world for future generations. Ending drone warfare is a concrete step we can and must take.

After the statements of Hartsough and the others, the judge declared that prison would serve "no purpose."

A second anti-drone trial is scheduled later this year for another group of five people arrested at Beale this past April 30.